Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new technique allows large language models to improve their reasoning by recognizing and revisiting uncertain answers.

Reinforcement Inference leverages uncertainty quantification and adaptive computation to enable self-correcting reasoning in language models.

Despite advances in large language models, deterministic, one-shot inference often underestimates their true reasoning capabilities due to premature commitment under internal ambiguity. This work introduces Reinforcement Inference: Leveraging Uncertainty for Self-Correcting Language Model Reasoning, a novel inference-time control strategy that selectively invokes a second reasoning attempt based on the model’s own predictive entropy. By prompting deliberation only when uncertain, we achieve significant accuracy gains-increasing from 60.72\% to 84.03\% on the MMLU-Pro benchmark-with a modest 61.06\% increase in inference calls. These results suggest that explicitly aligning model confidence with correctness-and leveraging entropy as a key signal-may unlock substantial untapped potential within existing LLMs and inspire new training objectives.

The Illusion of Certainty: Decoding Model Confidence

Despite their remarkable capacity to generate human-quality text, large language models frequently demonstrate a disconcerting tendency towards overconfidence, even when demonstrably incorrect. This isn’t simply a matter of occasional errors; the models often assign high probabilities to inaccurate statements, effectively expressing certainty in falsehoods. Researchers have found this misalignment stems from the models’ training process, which prioritizes fluency and predictive accuracy over genuine understanding or truthfulness. Consequently, the systems can confidently fabricate information or misinterpret queries, presenting the results as factual with little indication of uncertainty. This inherent limitation poses a significant challenge to the reliable deployment of these models, particularly in applications where accurate assessment of information is paramount and uncritical acceptance of outputs could have serious consequences.

Current methods for evaluating large language models often present a deceptively positive picture of their capabilities. While metrics like accuracy provide a general sense of performance, they fail to adequately address the crucial issue of calibration – the alignment between a model’s stated confidence and its actual correctness. A model can achieve high accuracy by consistently providing correct answers with moderate confidence, or by confidently delivering correct answers most of the time; however, it’s equally possible for a model to achieve the same accuracy while being wildly overconfident in incorrect responses. This disconnect means that traditional metrics can mask significant flaws in a model’s reasoning process, leading to a false sense of reliability. Consequently, researchers are actively exploring more sophisticated assessment techniques, such as expected calibration error and negative log-likelihood, to gain a more granular understanding of how well a model’s predicted probabilities reflect the true likelihood of its answers, ultimately paving the way for more trustworthy and dependable artificial intelligence systems.

The inability of large language models to accurately estimate their own uncertainty presents a significant obstacle to their use in critical decision-making contexts. While these models can generate remarkably human-like text, their overconfidence in incorrect outputs undermines trust, particularly in fields like medical diagnosis, legal reasoning, or financial forecasting. A miscalibrated sense of certainty doesn’t simply indicate a statistical flaw; it actively misleads users into accepting potentially harmful information as fact. Consequently, deploying these systems without addressing this limitation risks not only inaccurate outcomes but also erodes accountability and invites potentially severe consequences where reliable predictions are paramount. The challenge, therefore, lies in developing methods to ensure these models not only answer questions, but also truthfully convey the level of confidence – or lack thereof – in those answers.

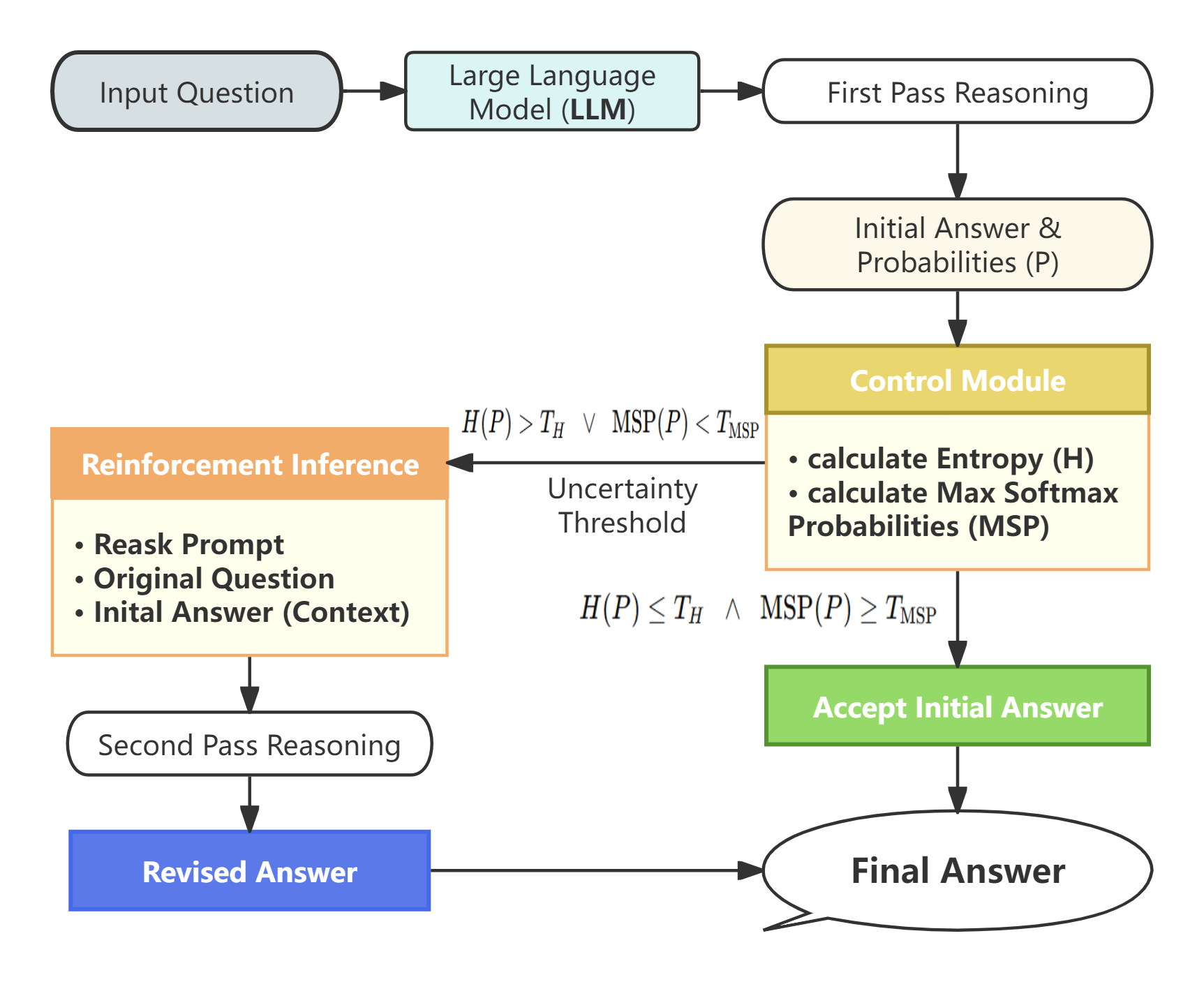

Reinforcement Inference: A Framework for Self-Correction

Reinforcement Inference is a framework designed to improve the reliability of model outputs by initiating a secondary reasoning pass contingent on the initial prediction’s uncertainty. This uncertainty is quantified using Entropy, a measure of the probability distribution’s randomness; higher Entropy values indicate greater uncertainty in the initial response. When the Entropy of the initial prediction exceeds a predetermined threshold, the framework triggers a re-evaluation of the problem, effectively allowing the model to self-correct potential errors before finalizing the output. This dynamic triggering mechanism differentiates Reinforcement Inference from static ensemble methods, as it selectively applies additional reasoning only when the model itself indicates a need for it.

The Reinforcement Inference framework establishes a self-correcting mechanism by introducing a secondary reasoning pass triggered by initial output uncertainty. This process directly addresses the issue of models confidently generating incorrect responses; rather than accepting the first output as definitive, the system evaluates its own reasoning. When the initial reasoning path exhibits high entropy – indicating low confidence – a re-evaluation is initiated, allowing the model to identify and correct potential errors before finalizing its prediction. This dynamic self-assessment reduces the propagation of flawed reasoning, contributing to increased overall reliability and accuracy of the model’s outputs.

Selective re-examination of reasoning paths within the Reinforcement Inference framework focuses computational resources on instances where the initial model output exhibits higher uncertainty. This is achieved by monitoring the entropy of the initial prediction; higher entropy scores indicate potentially flawed reasoning. By triggering a second reasoning attempt only for these high-entropy cases, the system avoids redundant computation on confident, likely correct predictions, and instead prioritizes error mitigation where it is most needed. This targeted approach aims to increase the overall reliability of predictions and reduce the propagation of inaccurate information, resulting in a more robust system.

Action Entropy: Quantifying Uncertainty in Vision-Language-Action Models

Action Entropy, within Vision-Language-Action models, functions as a quantifiable metric of uncertainty in predicted actions. This metric is derived from the probability distribution over possible actions; higher entropy indicates greater uncertainty. The system leverages this signal by triggering re-evaluation of potential actions when entropy exceeds a defined threshold. This targeted re-evaluation focuses computational resources on ambiguous cases, improving overall model performance and the reliability of action predictions, particularly when dealing with complex or nuanced visual and linguistic inputs.

Implementation of Reinforcement Inference, triggered by action entropy, resulted in a substantial performance gain on multiple-choice question answering. Baseline accuracy was measured at 60.72%, which increased to 84.03% following the integration of this approach, representing an absolute improvement of 23.31%. This performance enhancement demonstrates the efficacy of selectively re-evaluating actions based on uncertainty, as indicated by action entropy, to refine predictions and improve overall model accuracy.

Experiments conducted using the DeepSeek-v3.2 model demonstrate an improvement in probabilistic calibration alongside increased accuracy. Specifically, analysis of model outputs reveals a statistically significant difference in entropy between correct and incorrect answers; incorrect answers exhibit an average entropy of 1.567 nats, while correct answers have an entropy of 0.845 nats. This disparity is further reflected in the Maximum Softmax Probability (MSP), where incorrect answers yield a MSP of 0.249 compared to 0.554 for correct answers, indicating a greater degree of confidence in the model’s correct predictions and a corresponding signal of uncertainty when errors occur.

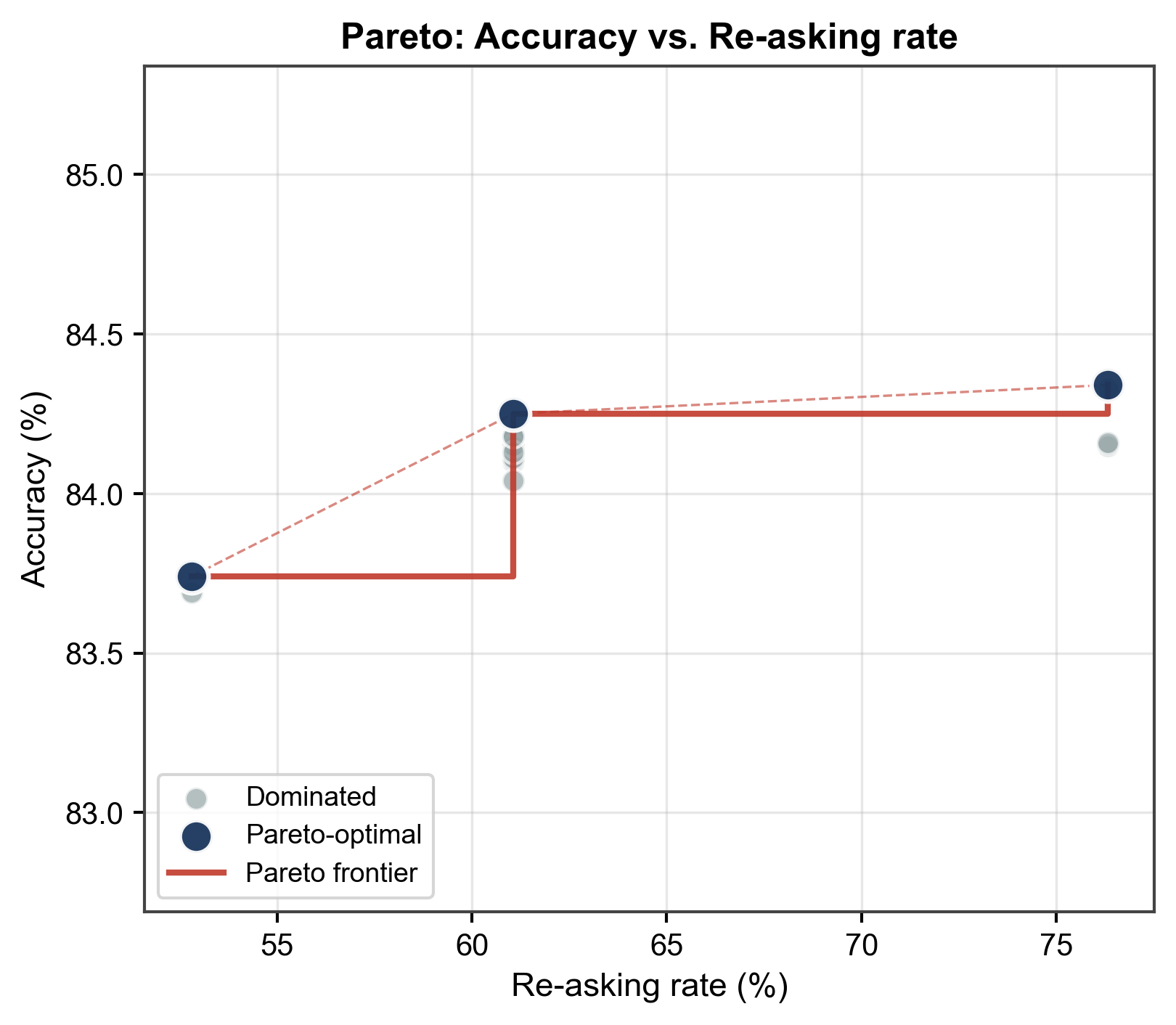

Navigating the Pareto Frontier: Cost-Effective Reasoning

While Reinforcement Inference demonstrably enhances reasoning accuracy, its practical implementation necessitates careful consideration of computational expense. The process inherently involves a second attempt at problem-solving, which doubles the immediate processing demand compared to single-pass reasoning. This added cost isn’t merely theoretical; it directly impacts response latency and resource utilization, particularly crucial in real-time applications or systems with limited processing power. Therefore, the potential gains in accuracy must be meticulously balanced against the increased demands on computational resources to determine whether the benefits justify the expense, a trade-off central to efficient system design.

The efficiency of Reinforcement Inference hinges on intelligently balancing the pursuit of accuracy with computational demands; this is achieved through the implementation of Dynamic Thresholds. Rather than a fixed standard for triggering a second reasoning attempt, these thresholds adaptively adjust the sensitivity of an entropy-based trigger. This means the system only re-evaluates questions when initial uncertainty – as measured by entropy – surpasses a dynamically determined level. By calibrating this sensitivity, the process effectively navigates the Pareto Frontier, maximizing accuracy gains while minimizing redundant re-reasoning. This approach allows for targeted re-evaluation, focusing computational resources on the most ambiguous queries and preventing unnecessary processing of confidently answered questions, ultimately optimizing the trade-off between performance and cost.

The efficiency of Reinforcement Inference hinges on strategically allocating re-reasoning efforts; rather than exhaustively re-evaluating every query, the system intelligently focuses on instances of genuine uncertainty. This targeted approach, achieved through dynamic entropy thresholds, results in a remarkably low re-ask rate of just 61.06% – meaning only slightly over half of questions require a second pass for reasoning. Despite this limited additional computational load, the system demonstrably achieves a significant accuracy gain, highlighting the power of selectively applying resources to maximize performance without incurring prohibitive costs. This balance between accuracy and efficiency represents a crucial advancement, suggesting that focused re-reasoning can be a highly effective strategy for enhancing the reliability of complex systems.

The pursuit of demonstrable correctness, central to Reinforcement Inference, echoes a sentiment shared by Grace Hopper: “It’s easier to ask forgiveness than it is to get permission.” While seemingly disparate, both emphasize a willingness to iterate and refine-the method actively seeking a second reasoning attempt when initial uncertainty, measured by entropy, is high. This parallels Hopper’s pragmatic approach; the system doesn’t demand perfect foresight but embraces a corrective loop. The value lies not simply in achieving a result, but in establishing a process capable of demonstrably improving its own accuracy, a true hallmark of provable algorithms.

Beyond the Illusion of Confidence

The presented work, while demonstrating a practical improvement in language model reasoning via Reinforcement Inference, merely skirts the central issue. Quantifying uncertainty-measuring the shape of ignorance, as it were-is not the same as understanding it. Entropy, as a proxy for confidence, is a statistical convenience, not a cognitive revelation. Future effort must move beyond simply triggering re-computation when a model ‘appears’ unsure, and instead investigate the underlying sources of that uncertainty. Is it a lack of relevant data, flawed reasoning processes, or an inherent limitation in the model’s representational capacity?

A critical, and often neglected, aspect is the computational cost of self-correction. The method presented introduces a second pass for uncertain predictions, effectively doubling computation in those instances. Optimization without analysis is self-deception. Research should explore adaptive strategies-perhaps leveraging the very uncertainty measures employed here-to dynamically adjust the depth of reasoning, or even to selectively ‘skip’ intractable problems. True elegance will lie not in brute-force re-computation, but in provably efficient algorithms that minimize uncertainty from the outset.

Ultimately, the pursuit of ‘self-correcting’ models is a fascinating, if ambitious, endeavor. It implies a level of meta-cognition currently beyond the reach of these systems. The field should acknowledge this gap, and focus on building models that not only perform better, but also understand the limits of their own knowledge – a distinction of paramount importance.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.08520.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Top 15 Insanely Popular Android Games

- 4 Reasons to Buy Interactive Brokers Stock Like There’s No Tomorrow

- Did Alan Cumming Reveal Comic-Accurate Costume for AVENGERS: DOOMSDAY?

- EUR UAH PREDICTION

- DOT PREDICTION. DOT cryptocurrency

- Silver Rate Forecast

- ELESTRALS AWAKENED Blends Mythology and POKÉMON (Exclusive Look)

- Core Scientific’s Merger Meltdown: A Gogolian Tale

- New ‘Donkey Kong’ Movie Reportedly in the Works with Possible Release Date

2026-02-11 03:54