Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research bridges the gap between Gaussian processes and recurrent neural networks to reveal the underlying principles governing deep learning.

This review explores the theoretical foundations of recurrent neural networks through the lens of field theory, Bayesian inference, and Gaussian processes, focusing on their behavior and properties.

Understanding the collective behavior of deep neural networks remains a significant challenge despite recent advances in machine learning. These lecture notes, ‘Lecture notes: From Gaussian processes to feature learning’, provide a theoretical framework for analyzing recurrent and deep networks through the lens of Bayesian inference and field theory. By connecting the neural network Gaussian process limit to adaptive kernel methods, the work elucidates the mechanisms underlying feature learning and offers insights into kernel rescaling approaches. Could this theoretical foundation ultimately unlock more robust and interpretable deep learning architectures?

Beyond Simple Scaling: Unveiling the Principles of Network Behavior

Despite the remarkable progress of deep learning, the intricacies of complex networks continue to pose a substantial challenge to researchers. These networks, whether biological, social, or technological, exhibit behaviors that often surpass the predictive capabilities of even the most sophisticated algorithms. The difficulty lies not simply in the scale of these systems – though size certainly contributes – but in the non-linear interactions between their constituent parts. Traditional analytical methods, designed for simpler, more predictable systems, frequently fail to capture the emergent properties that arise from these interactions, hindering a complete understanding of network dynamics. Consequently, accurately modeling and forecasting the behavior of these complex networks requires innovative approaches that move beyond simply increasing computational power and delve into the fundamental principles governing their collective behavior.

Current analytical techniques often fall short when applied to complex neural networks because they primarily focus on individual components or linear interactions, failing to adequately represent the emergent properties that arise from the intricate web of connections. These properties – behaviors not predictable from the characteristics of isolated neurons – stem from the non-linear dynamics and feedback loops inherent in these systems. Consequently, predictive power is significantly limited; a network might perform remarkably well on a given task, yet remain largely inscrutable, hindering efforts to improve its robustness, efficiency, or generalizability. This disconnect between performance and understanding necessitates a shift beyond simply scaling existing architectures and toward fundamentally new network paradigms capable of revealing – and leveraging – these collective behaviors.

A Statistical Lens: Understanding Networks Through Mean-Field Theory

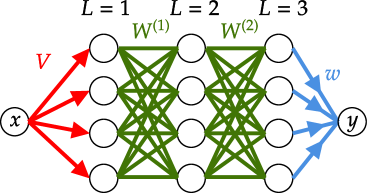

Mean-Field Theory (MFT) offers an analytical approach to modeling the behavior of complex systems comprised of numerous interacting components, such as deep neural networks and recurrent neural networks. Rather than tracking the state of each individual unit, MFT approximates the system’s dynamics by considering the average effect of all other units on a given unit; this simplification is justified when dealing with systems where the number of interacting elements is sufficiently large. The core assumption involves replacing the interactions with a single, effective field that represents the average influence. This allows for the derivation of self-consistent equations describing the system’s overall behavior, significantly reducing computational complexity while retaining key characteristics of the network’s dynamics. While inherently an approximation, MFT provides valuable insights into phenomena like phase transitions and collective behavior in these large-scale networks.

Mean-Field Theory simplifies the analysis of complex networks by replacing the interactions between individual elements with interactions with average quantities. Rather than tracking the state of each neuron or node, this approach models each element as experiencing the average effect of the entire network. This simplification reduces computational complexity from O(N^2) to O(N), where N is the number of elements, while still capturing essential dynamical features such as the network’s overall activity level and response to stimuli. The validity of this approximation rests on the assumption that fluctuations around the average are small relative to the average itself, allowing for accurate predictions of collective network behavior without detailed knowledge of individual element states.

Mean-field theory facilitates the analysis of neural networks by shifting the focus from the precise state of each individual neuron to the average behavior of a large population of neurons. Instead of tracking the activity of N units, the theory models the interaction of a single ‘representative’ neuron with an average field created by all other neurons. This average field is determined by the collective activity of the network, effectively reducing the complexity of the system. Consequently, network-level properties such as the overall firing rate, synchrony, and response to stimuli can be derived from equations governing this average behavior, providing insights into emergent phenomena not apparent from single-neuron analysis.

Quantifying the Unknown: Bayesian Inference and Gaussian Processes

Bayesian inference provides a systematic approach to estimating network parameters by treating them as random variables with probability distributions rather than fixed values. This allows for the incorporation of \text{prior knowledge} about the parameters – representing pre-existing beliefs or data – which is then combined with observed data via Bayes’ Theorem to produce a \text{posterior distribution}. Crucially, this posterior distribution doesn’t provide a single “best” parameter value, but rather a complete probability distribution reflecting the uncertainty in the estimate. Quantifying this uncertainty is achieved through metrics derived from the posterior, such as the standard deviation or credible intervals, offering a measure of confidence in the network’s parameters and predictions. This contrasts with traditional methods that yield point estimates without explicit uncertainty quantification.

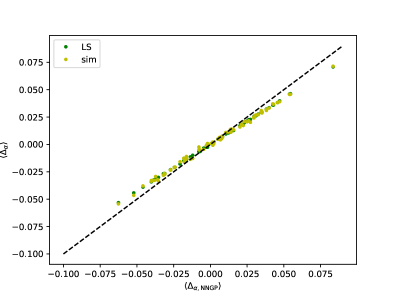

Neural Network Gaussian Processes (NNGPs) address the challenge of applying Gaussian process methodology to networks containing hidden layers by providing a means to analytically determine the posterior distribution over network weights. This is achieved by leveraging the fact that, under certain initialization schemes and network architectures, the distribution of hidden layer activations remains Gaussian throughout training. Consequently, the covariance between any two outputs can be computed directly, yielding a closed-form expression for the predictive distribution p(y^<i> | X^</i>, X, y) . This allows for the quantification of predictive uncertainty – specifically, the variance of the prediction – and facilitates the calculation of correlations between outputs, providing a comprehensive probabilistic model for neural network behavior without requiring Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) methods.

By applying Bayesian inference and Neural Network Gaussian Processes (NNGPs) in conjunction with linear regression, it becomes possible to characterize the functional relationships between a neural network’s input features and its resulting outputs. This is achieved by modeling the network’s weights as probability distributions and utilizing linear regression to approximate the expected output given a specific input. The resulting model allows for the calculation of predictive means and variances, providing a quantifiable understanding of how changes in input features affect network predictions and enabling the estimation of uncertainty associated with those predictions; specifically, E[f(x)] and Var[f(x)] can be determined, where f(x) represents the network’s output for input x .

Mapping the Dynamics: Modeling Time Evolution with Fokker-Planck

The Fokker-Planck equation is a partial differential equation describing the time evolution of a probability density function for the state of a dynamical system. In the context of neuronal networks, this equation models how the distribution of neuronal states – such as membrane potentials or synaptic weights – changes over time due to stochastic forces and deterministic dynamics. Specifically, it provides a continuous, probabilistic representation of learning, allowing researchers to track the evolution of network parameters during training or adaptation. The equation incorporates a drift term representing the average change in state and a diffusion term quantifying the effect of noise, and can be expressed generally as \frac{\partial P(x,t)}{\partial t} = - \frac{\partial}{\partial x} [A(x,t)P(x,t)] + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} [B(x,t)P(x,t)] , where P(x,t) is the probability density, and A(x,t) and B(x,t) define the drift and diffusion coefficients, respectively.

The Large Deviation Principle, when applied in conjunction with the Fokker-Planck Equation, allows for the quantitative analysis of both commonly occurring (typical) and infrequent (rare) events within neuronal network dynamics. This is achieved by examining the asymptotic behavior of probabilities of observing states far from the typical trajectory, providing a means to calculate the rate at which these rare events occur. Specifically, the principle facilitates the calculation of the probability of observing large deviations from the mean behavior, offering insights into the network’s susceptibility to instability and its capacity to maintain stable states despite perturbations. This approach is crucial for assessing network robustness, as it allows for the prediction of how the network will respond to extreme or unusual inputs, and for identifying parameters that enhance its resilience to failure or undesirable states.

The Fokker-Planck equation, when applied to recurrent neural networks, provides a means to model the temporal evolution of neuronal states and their associated probability distributions. This is particularly relevant to understanding fading memory phenomena, where the network’s ability to retain information decays over time. Recurrent networks, due to their feedback connections, exhibit complex internal dynamics; the Fokker-Planck approach allows for the quantification of these dynamics, effectively tracking how initial states diffuse and evolve under network processing. Analysis using this framework can reveal the rates of memory decay, the influence of network parameters on stability, and the conditions under which the network can maintain persistent activity – all crucial aspects of understanding how these networks process and retain sequential information. \frac{\partial P(x,t)}{\partial t} = - \frac{\partial}{\partial x} [A(x)P(x,t)] + \frac{1}{2} \frac{\partial^2}{\partial x^2} [B(x)P(x,t)]

A Unified Lens: Toward a Predictive Theory of Network Function

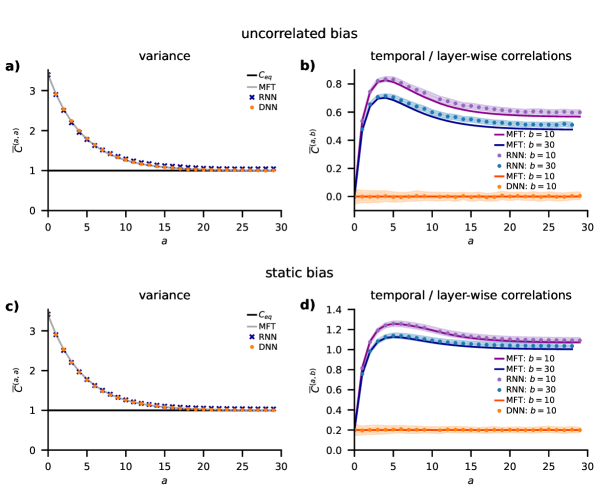

A robust analytical toolkit for dissecting complex networks is achieved by synergistically combining Mean-Field Theory, Bayesian Inference, and the Fokker-Planck Equation. This integrated framework transcends purely empirical observations, enabling researchers to model network behavior with a deeper, more fundamental understanding. Mean-Field Theory simplifies the analysis by approximating interactions between network elements, while Bayesian Inference provides a principled way to incorporate prior knowledge and quantify uncertainty. The Fokker-Planck Equation, a powerful tool from stochastic processes, then allows for the description of the evolving probability distributions of network states. This combination not only facilitates the prediction of network dynamics but also offers insights into the underlying mechanisms governing collective behavior, proving particularly valuable when studying recurrent neural networks and their correlation properties.

Traditional network analysis often relies on describing what happens within a system, cataloging observed patterns without explaining why those patterns emerge. This research transcends purely empirical observation by establishing a theoretical foundation for understanding network dynamics. Through the integration of mathematical tools – including Mean-Field Theory and the Fokker-Planck Equation – the study moves beyond simply characterizing network behavior to predicting it, and crucially, revealing the underlying mechanisms that govern it. This allows for a deeper, more generalizable comprehension of complex systems, offering insights that are not limited to the specific networks initially studied and enabling the application of these principles to a broader range of scientific challenges. The result is not merely a description of network structure, but a predictive model of network function, built on fundamental mathematical principles.

Investigations into recurrent neural networks, utilizing an established analytical framework, reveal surprising connections to their feedforward counterparts. While equal-time correlations within recurrent networks closely mirror those observed in deep feedforward networks, analysis of unequal-time correlations unveils previously unobserved behaviors – suggesting a richer dynamic structure than previously understood. This work demonstrates that the resulting Cumulant Generating Function (CGF) polynomial, crucial for characterizing network behavior, achieves a degree of 2 when applied to non-scalar Gaussian variables – a result with significant implications for simplifying and understanding the complex interactions within these networks, and potentially informing more efficient network designs.

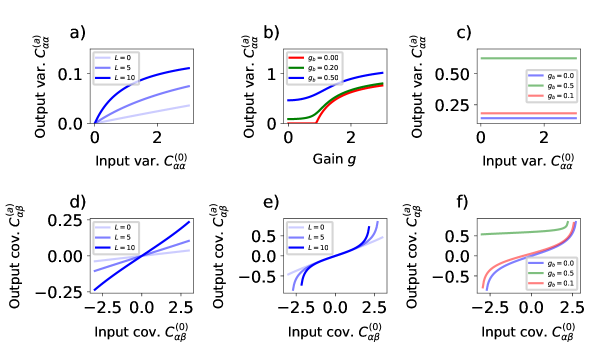

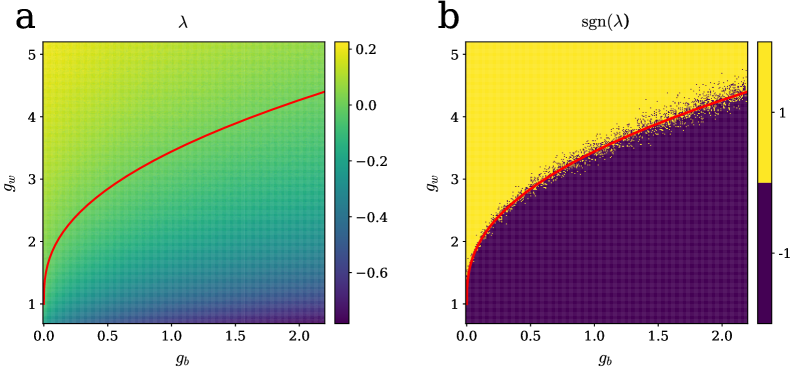

![The depth scaling of information propagation in deep networks reveals a phase diagram distinguishing between regular and chaotic behaviors, dependent on the variance of the weight prior <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">\sigma_{w}^{2}</span> and bias term <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">\sigma_{b}^{2}</span> with a <span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">tanh</span> activation function (adapted from [33]).](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.12855v1/figures/depth_scales1.png)

The exploration of recurrent neural networks, as detailed in the study, necessitates a distillation of complex interactions. This pursuit of understanding network dynamics through Bayesian inference and Gaussian processes mirrors a core philosophical tenet: clarity is the minimum viable kindness. John Stuart Mill observed, “The only freedom which deserves the name is that of pursuing our own good in our own way.” Similarly, this work seeks to define the ‘freedom’ within these networks – their capacity for learning – by reducing complexity and illuminating fundamental principles. The application of tools like the Fokker-Planck equation isn’t merely mathematical; it’s an attempt to reveal the inherent logic governing these systems, stripping away extraneous detail to expose the essential mechanisms at play.

The Road Ahead

The exercise, tracing recurrent networks back to the ostensibly more fundamental languages of field theory and Gaussian processes, reveals less a breakthrough than a clarifying subtraction. The proliferation of parameters in deep learning, so often justified by empirical performance, remains stubbornly opaque. To model the model, to build complexity upon complexity, feels intrinsically unstable – a system requiring ever more instruction, thereby admitting its inherent failure to achieve simplicity. The true test lies not in achieving ever-higher accuracy on benchmark tasks, but in reducing the necessary assumptions, the scaffolding required to coax intelligence from silicon.

Further inquiry should not dwell on increasingly elaborate approximations of network dynamics – the Fokker-Planck equation, for instance, offers diminishing returns. Instead, attention should be directed toward identifying the minimal sufficient conditions for learning. What principles, if any, constrain the solution space so drastically that complex architectures become unnecessary? The invocation of Wick’s theorem and mean-field theory, while mathematically elegant, merely pushes the problem of intractability one level deeper.

Ultimately, the goal is not to build a better neural network, but to understand why such things work at all. A truly insightful theory will not predict behavior, but explain it – revealing the necessity of observed complexity, or, more elegantly, demonstrating its superfluity. Clarity, after all, is not merely a courtesy to the reader, but a fundamental requirement of any viable scientific explanation.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.12855.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Building 3D Worlds from Words: Is Reinforcement Learning the Key?

- Securing the Agent Ecosystem: Detecting Malicious Workflow Patterns

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- The Best Directors of 2025

- Mel Gibson, 69, and Rosalind Ross, 35, Call It Quits After Nearly a Decade: “It’s Sad To End This Chapter in our Lives”

- TV Shows Where Asian Representation Felt Like Stereotype Checklists

- Most Famous Richards in the World

- Games That Faced Bans in Countries Over Political Themes

- Celebs Who Married for Green Cards and Divorced Fast

2026-02-16 18:47