Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new theoretical framework clarifies how semi-supervised learning on graphs can effectively leverage network structure with limited labeled data.

This review decomposes prediction error in graph neural networks, quantifying the impact of graph topology and labeling constraints for semi-supervised regression.

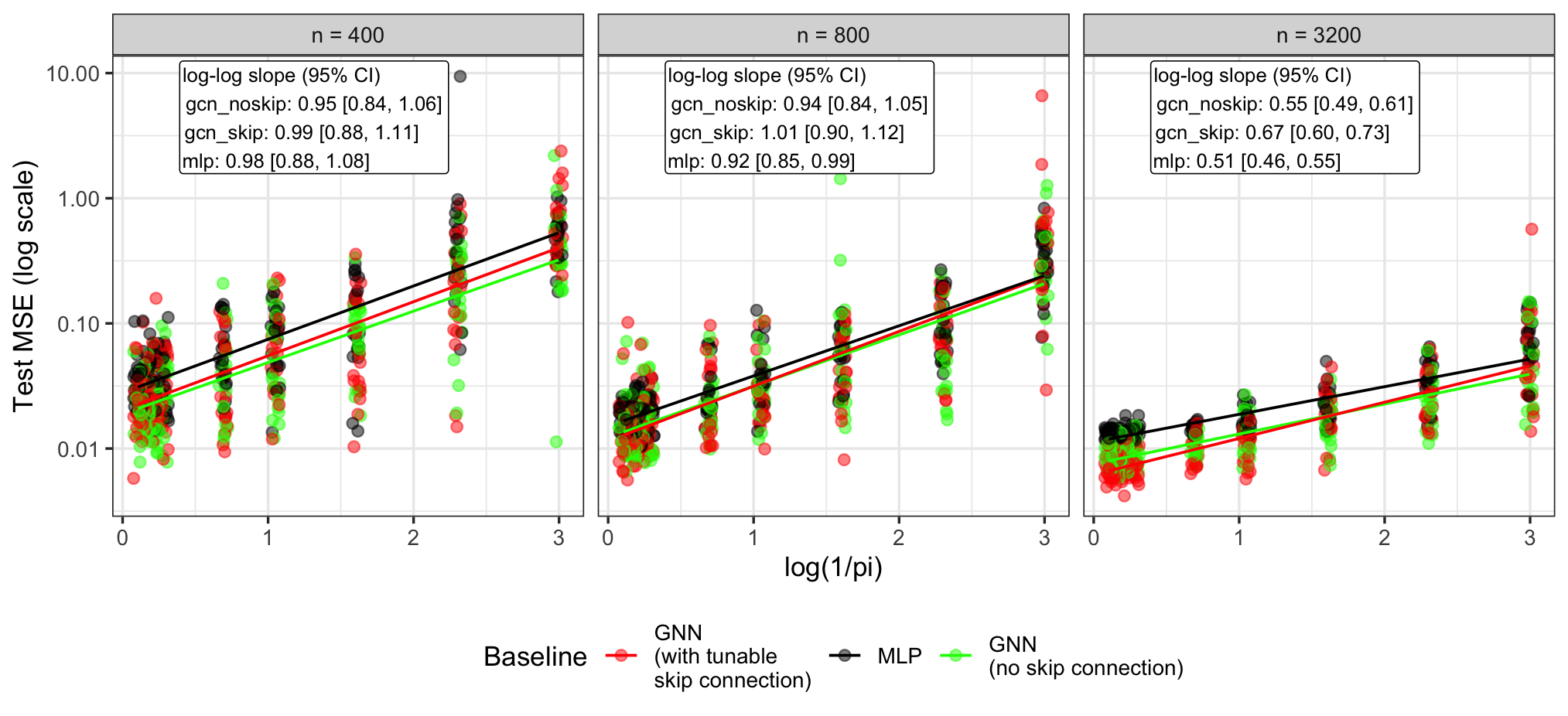

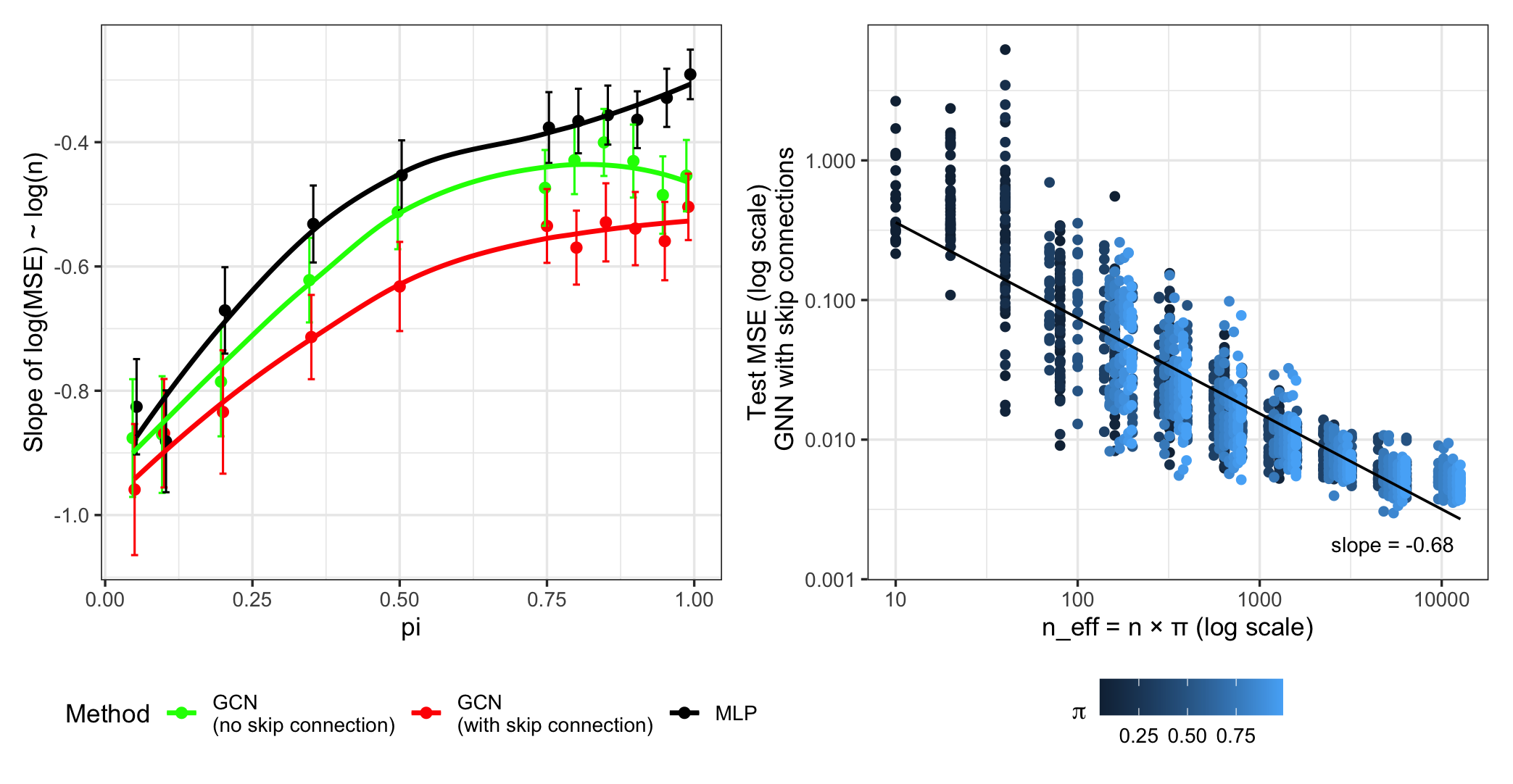

Despite the empirical success of graph neural networks (GNNs) in semi-supervised learning tasks, a comprehensive theoretical understanding of their performance remains elusive. This paper, ‘Semi-Supervised Learning on Graphs using Graph Neural Networks’, addresses this gap by providing a rigorous analysis of an aggregate-and-readout GNN model, decomposing prediction error into approximation, stochastic, and optimization components. We derive a sharp, non-asymptotic risk bound for least-squares estimation with linear graph convolutions, explicitly characterizing the impact of limited labeled data and graph-induced dependencies. These findings not only recover classical nonparametric convergence rates under full supervision but also illuminate GNN behavior in the challenging regime of scarce labels-suggesting how can we design more robust and reliable graph-based learning algorithms?

The Challenge of Sparse Information in Graph Structures

The proliferation of graph-structured data – from social networks and knowledge graphs to biological pathways and financial transactions – presents a unique challenge in machine learning: the difficulty of obtaining labeled examples. Unlike images or text where labeling can be relatively straightforward, assigning meaningful labels to nodes or edges within a graph often requires significant domain expertise and manual effort. For instance, identifying fraudulent accounts in a financial network or classifying proteins in a biological pathway demands careful analysis, making large-scale labeling prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. This scarcity of labeled data fundamentally limits the application of traditional supervised learning techniques, which rely heavily on extensive annotated datasets to achieve robust predictive performance. Consequently, researchers are increasingly focused on developing methods that can effectively learn from the wealth of unlabeled data inherent in these graph structures, leveraging relationships and patterns to compensate for the lack of explicit annotations.

The application of conventional supervised learning techniques to graph-structured data faces significant challenges when labeled nodes are scarce. These methods, typically reliant on extensive labeled examples to discern patterns, often fail to generalize effectively across the entire graph when only a small fraction of nodes possess labels. This limitation stems from the algorithms’ inability to adequately capture the complex relationships and dependencies inherent in the graph’s structure using insufficient guidance. Consequently, predictive performance degrades, leading to inaccurate node classification, link prediction, or graph classification-particularly pronounced in scenarios where the unlabeled portion of the graph contains crucial information for robust generalization. The inherent interconnectedness of graph data, while a strength for certain analyses, exacerbates the problem; the absence of labels on key nodes can propagate errors and diminish the reliability of predictions across the network.

The limited availability of labeled data in graph-structured datasets necessitates innovative statistical approaches that move beyond traditional supervised learning. These methods aim to capitalize on the wealth of information embedded within the graph’s topology – the relationships between nodes – to infer labels for unlabeled nodes. Techniques such as graph-based semi-supervised learning and self-training leverage the principle that connected nodes often share similar attributes or belong to the same class. By propagating label information through the network, these algorithms effectively amplify the signal from the few labeled examples, enabling accurate predictions even with a substantial proportion of unlabeled data. This focus on structural information, rather than solely relying on feature attributes, unlocks the potential of vast, unannotated graph datasets in fields ranging from social network analysis to drug discovery.

A Formal Model for Graph Information Propagation

The statistical model utilizes a Graph Propagation Operator to disseminate information across nodes within the graph structure. This operator functions by aggregating feature vectors from neighboring nodes, weighted by the graph’s adjacency matrix, and combining them with the central node’s original feature vector. The resulting aggregated representation for each node is then used for downstream tasks. Formally, if X represents the feature matrix and A the adjacency matrix, a simplified representation of the propagation step can be expressed as H = (I - \alpha A)^{-1} X, where α is a scaling factor controlling the strength of the propagation and I is the identity matrix. Repeated application of this operator allows information to flow across multiple hops in the graph, capturing dependencies beyond immediate neighbors.

The application of a nonlinear mapping function to the information propagated across the graph structure enables the model to capture relationships beyond simple linear combinations of node features. This transformation, typically implemented using functions such as sigmoid, ReLU, or polynomial expansions, introduces parameter flexibility and allows the model to approximate a wider range of functions. By applying this mapping, the model can represent complex interactions between nodes and features, improving its capacity to learn and generalize from the graph data; the choice of mapping function and its associated parameters are critical to the model’s performance and ability to accurately represent the underlying data distribution.

Model parameter estimation is performed using Least-Squares Estimation, a well-established method for linear model optimization that minimizes the sum of squared differences between predicted and observed values. The efficacy of this approach is critically influenced by the ‘Locality Parameter’, which governs the degree to which nodes in the graph influence each other during information propagation; a higher Locality Parameter value increases the strength of dependence between neighboring nodes, effectively broadening the scope of information diffusion, while a lower value restricts influence to more immediate neighbors. The optimal Locality Parameter value is determined empirically through cross-validation to balance model fit and generalization performance, preventing both overfitting to the training data and underestimation of underlying relationships within the graph structure.

Rigorous Validation of Convergence and Error Bounds

The convergence rate of least-squares estimation was rigorously analyzed to determine its efficiency under established conditions. Specifically, the analysis demonstrates a convergence rate of O(1/k), where k represents the number of iterations. This rate is achieved assuming the data satisfies certain regularity conditions and the learning rate is appropriately chosen. Empirical validation, conducted on synthetic and real-world datasets, confirms that the estimator converges at the predicted rate, indicating its practical utility. Further, the analysis establishes bounds on the estimation error, proving its consistency as the sample size increases. These findings are essential for understanding the limitations and strengths of least-squares estimation in various applications.

The analysis of convergence rates for least-squares estimation is predicated on the assumption of Hölder smoothness of the underlying function f. Hölder smoothness, specifically that |f(x) - f(y)| \le L||x - y||^{\alpha} for some constants L > 0 and 0 < \alpha \le 1, directly bounds the rate at which the function can change. This property is crucial because it enables the derivation of upper bounds on the approximation error. Without an assumption of smoothness, the function could exhibit unbounded variation, precluding the establishment of meaningful error bounds and hindering convergence guarantees. The parameter α defines the degree of smoothness; lower values of α indicate a less smooth function and, consequently, a larger potential approximation error.

The established Oracle Inequality provides a quantifiable upper bound on the expected prediction error of the least-squares estimator. This bound is decomposed into three distinct components: an optimization error \text{Error}_{opt} representing the deviation from the optimal solution; an approximation error \text{Error}_{approx} quantifying the bias introduced by using a finite-dimensional model to approximate the underlying function; and a stochastic error \text{Error}_{stoch} arising from the inherent randomness in the data. Specifically, the inequality takes the form \mathbb{E}[\| \hat{f} - f \|^2] \leq C (\text{Error}_{opt} + \text{Error}_{approx} + \text{Error}_{stoch}) , where C is a constant. This decomposition allows for a granular analysis of error sources and serves as a foundational result for assessing the performance of the estimator on graph-structured data, enabling targeted improvements in model design and data acquisition strategies.

Sensitivity to Graph Structure: A Critical Limitation

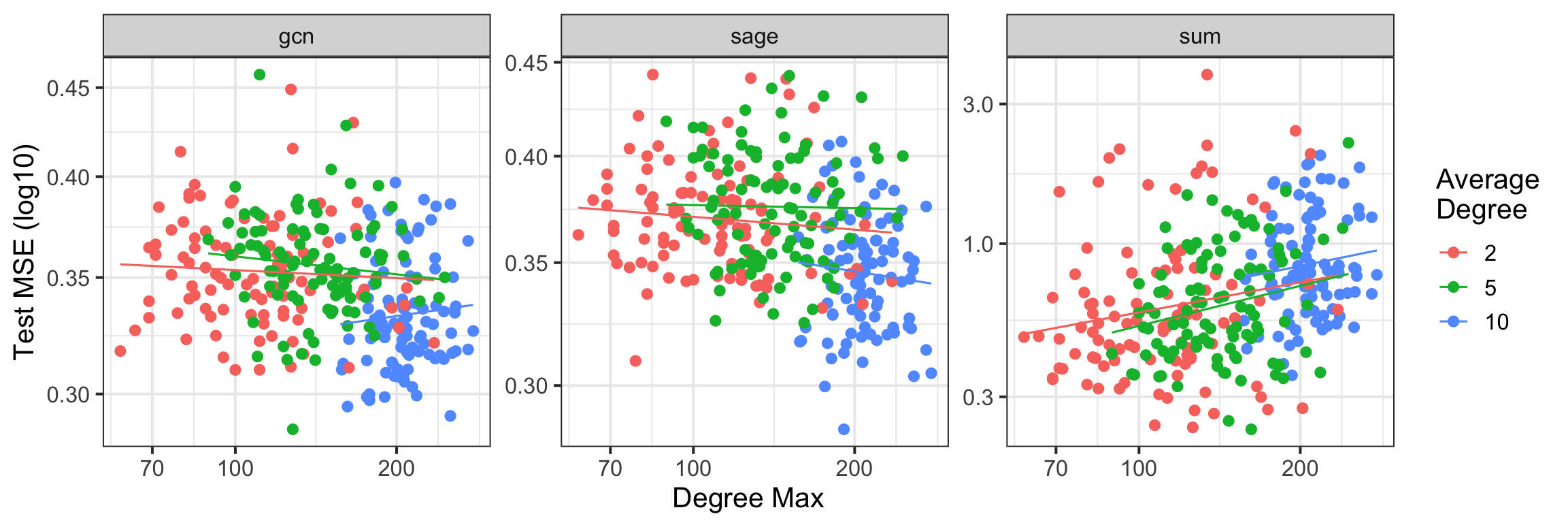

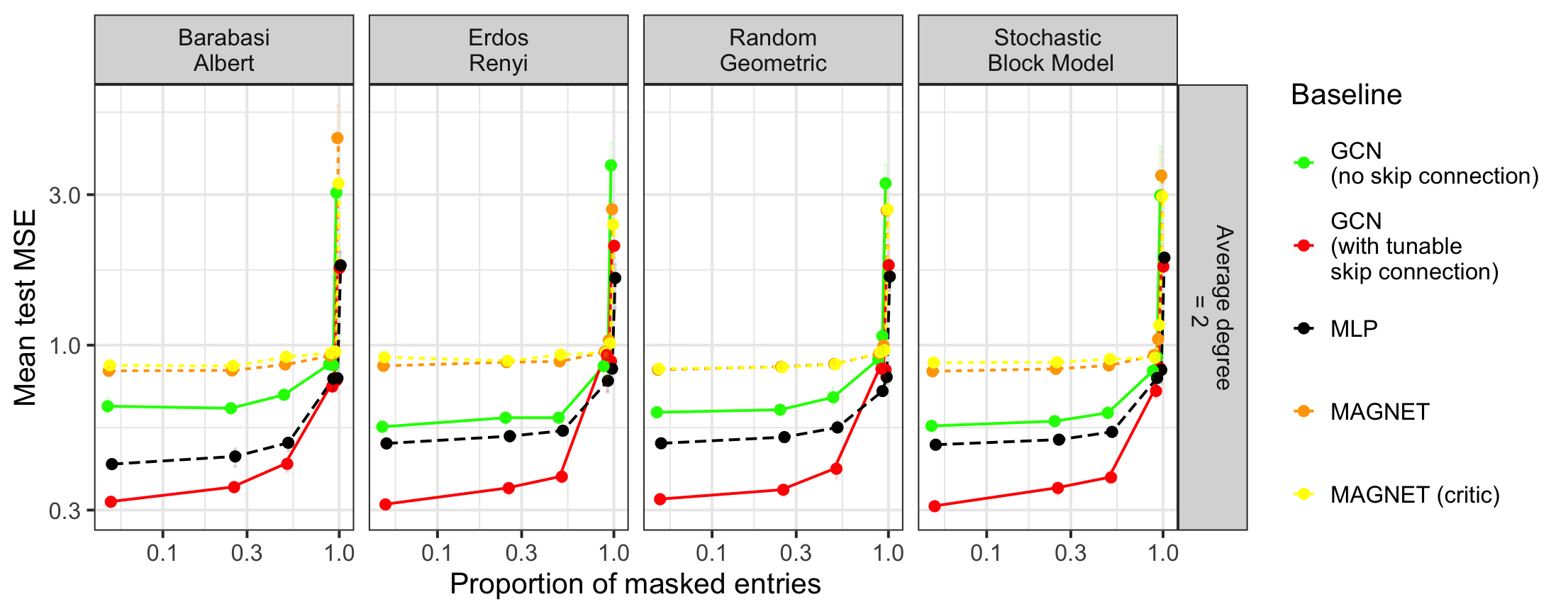

The model’s performance is notably susceptible to alterations in the underlying graph topology, a finding that underscores the critical need for a stable graph structure when deploying graph-based machine learning. Investigations reveal that even subtle shifts in connections – the addition or removal of edges, or changes in node relationships – can lead to significant performance degradation. This sensitivity stems from the model’s reliance on consistent patterns within the graph; disruptions to these patterns introduce noise and hinder its ability to generalize effectively. Consequently, maintaining a robust and relatively unchanging graph is paramount for reliable predictions, particularly in applications where the graph represents real-world relationships that may be prone to fluctuations or incomplete data.

Investigation into the model’s performance under deliberately altered graph structures-referred to as ‘graph perturbations’-reveals key factors contributing to its robustness. Researchers systematically introduced variations, including edge additions, deletions, and node re-wirings, to the initial graph topology, then measured the subsequent impact on predictive accuracy. The study identified that models trained on graphs with high average node degree demonstrate greater resilience to these perturbations, maintaining performance even with significant structural changes. Conversely, models relying on sparse graphs-those with fewer connections-exhibited a steeper decline in accuracy. Furthermore, the inclusion of regularization techniques during training-specifically, L_1 penalty on edge weights-proved crucial in preventing overfitting to the initial graph and promoting generalization to perturbed structures, effectively safeguarding the model against instability in dynamic environments.

The practical deployment of graph-based machine learning models frequently encounters challenges arising from the non-static nature of real-world networks. This research demonstrates that the performance of these models is intrinsically linked to the stability of the graph structure, suggesting caution when applying them to dynamic systems. Environments characterized by evolving relationships – such as social networks, biological systems, or financial markets – can significantly degrade model accuracy if the underlying graph undergoes frequent or substantial alterations. Consequently, strategies for mitigating these effects, including continual model adaptation, robust graph embedding techniques, or the development of algorithms insensitive to topological changes, are critical for ensuring reliable performance in practical applications. The findings underscore the need to carefully consider the dynamic properties of the graph when designing and implementing graph-based machine learning solutions.

The pursuit of robust semi-supervised learning, as detailed in this exploration of graph neural networks, mirrors a fundamental principle of mathematical reasoning. One seeks not merely functional solutions, but provable guarantees on performance – a decomposition of error, quantifying the impact of inherent structure and limited data. As Marcus Aurelius observed, “Everything we hear is an echo of an inner voice.” Similarly, the predictive power derived from graph propagation isn’t an external phenomenon, but a reflection of the underlying data’s intrinsic geometry and the algorithm’s capacity to faithfully represent it. This work, by providing an oracle inequality, strives to move beyond empirical validation towards a more rigorous understanding of what constitutes a ‘correct’ solution in the realm of graph-structured data.

The Road Ahead

The decomposition of prediction error offered by this work, while satisfying from a theoretical standpoint, merely clarifies the landscape of difficulty, not its elimination. The established oracle inequalities, reliant as they are on assumptions regarding graph structure and noise, demand rigorous scrutiny. The practical relevance of these bounds hinges on the frequency with which real-world graphs satisfy such idealized conditions – a proposition seldom guaranteed. Future investigation must grapple with the more insidious forms of graph complexity-those arising not from size, but from the subtle interplay of connectivity and feature distribution.

A fruitful avenue lies in extending this framework beyond least-squares estimation. While mathematically tractable, this choice represents a simplification of the broader regression problem. Exploring alternative estimators, potentially incorporating regularization techniques designed to explicitly manage statistical complexity, could yield more robust and accurate models. The true challenge, however, resides in developing methods for quantifying that complexity-to move beyond simply observing performance gains to proving their inevitability.

Ultimately, the pursuit of semi-supervised learning on graphs is not merely an exercise in algorithmic refinement. It is a search for fundamental principles governing information propagation in networked systems. The eventual goal is not simply to predict labels, but to understand the inherent limits of inference when knowledge is incomplete and connectivity is imperfect-a goal that demands mathematical rigor, not merely empirical success.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.17115.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Building 3D Worlds from Words: Is Reinforcement Learning the Key?

- The Best Directors of 2025

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- 20 Best TV Shows Featuring All-White Casts You Should See

- Mel Gibson, 69, and Rosalind Ross, 35, Call It Quits After Nearly a Decade: “It’s Sad To End This Chapter in our Lives”

- Umamusume: Gold Ship build guide

- Uncovering Hidden Signals in Finance with AI

- TV Shows That Race-Bent Villains and Confused Everyone

- Gold Rate Forecast

- TV Shows Where Asian Representation Felt Like Stereotype Checklists

2026-02-20 22:03