Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research introduces an algorithm that significantly improves performance in repeated online negotiations by dynamically adjusting to price fluctuations.

This work establishes a tighter benchmark for online bilateral trade, achieving near-optimal regret bounds against fixed-price distributions in stochastic environments.

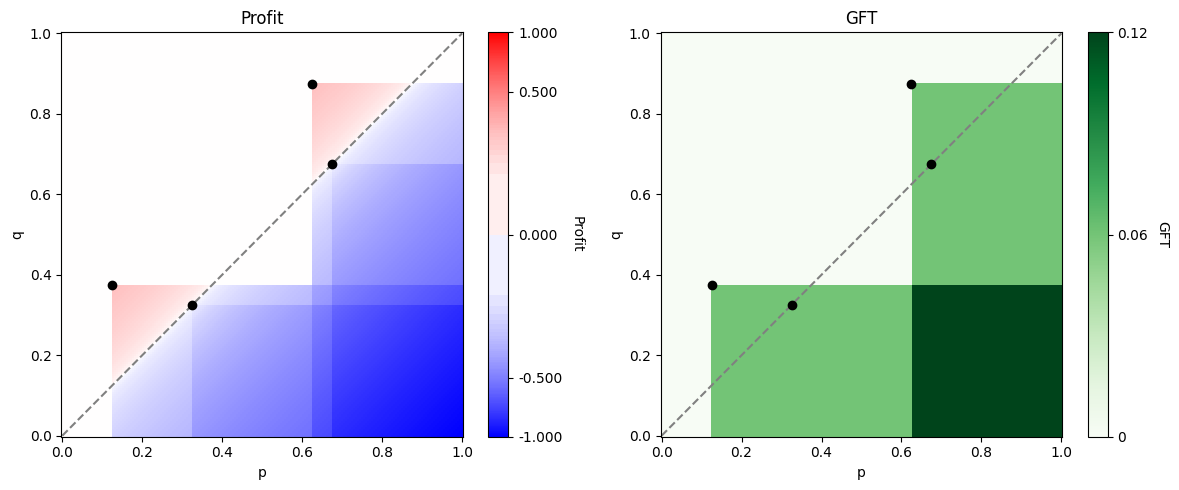

Existing algorithms for online bilateral trade often suffer linear regret when evaluated against a more refined benchmark focused on overall profit rather than round-by-round budget balance. This work, ‘A Stronger Benchmark for Online Bilateral Trade: From Fixed Prices to Distributions’, addresses this limitation by presenting the first algorithm to achieve sublinear regret against the optimal global budget balance in stochastic environments with one-bit feedback. Specifically, under the assumption of bounded valuation density, our approach achieves a regret of \widetilde{\mathcal{O}}(T^{3/4}). Does this result indicate a fundamental equivalence between learning optimal fixed prices and learning optimal price distributions for maximizing long-term gains in online bilateral trade?

The Foundations of Trade: Navigating Bilateral Exchange

At the heart of economic interaction lies the ‘Bilateral Trade Problem’, a foundational concept describing the simplest form of market exchange: a single seller and a single buyer. This seemingly straightforward scenario encapsulates the core challenges inherent in all economic transactions. The problem isn’t necessarily about whether a trade will occur, but at what price. Both parties possess distinct valuations for the good or service being exchanged, and reaching a mutually agreeable price requires navigating these individual assessments. This basic framework extends far beyond simple bartering; it underpins complex negotiations, auction dynamics, and even the functioning of entire markets, demonstrating that understanding this fundamental exchange is crucial for analyzing broader economic phenomena. The bilateral trade problem provides a vital starting point for modelling and understanding how incentives, information, and strategic behavior shape economic outcomes.

The very essence of exchange relies on the fact that a seller’s cost and a buyer’s benefit are rarely, if ever, public knowledge. This private valuation – the unique worth each party assigns to a good or service – fundamentally shapes the dynamics of trade. Because neither side can fully ascertain the other’s willingness to pay or accept, transactions aren’t simply determined by objective value. Instead, they emerge from a complex interplay of perceived value, strategic negotiation, and inherent uncertainty. Consequently, successful trades aren’t about revealing true valuations – which would eliminate potential gains – but rather about skillfully conveying information and navigating the landscape of incomplete knowledge to reach a mutually beneficial agreement. This hidden information is the bedrock upon which all market interactions are built, influencing pricing, quantities exchanged, and the overall efficiency of resource allocation.

When a seller and buyer engage in trade, a core challenge arises from the fact that each party rarely reveals their true willingness to pay or accept – a condition known as private valuations. This inherent lack of complete information fundamentally alters the dynamics of exchange. Consequently, effective trade necessitates strategies designed to navigate uncertainty and account for potential asymmetries in knowledge. These strategies aren’t simply about finding a mutually agreeable price; they involve signaling, screening, and mechanisms to mitigate the risk that one party exploits the other’s private information. The resulting negotiation processes, therefore, become complex games of information and inference, where both parties attempt to deduce the other’s valuation and position themselves for a favorable outcome. Ultimately, the success of any trade depends on how well these challenges of incomplete information are addressed and overcome.

The Dynamics of Repeated Interaction and Budgetary Constraints

Unlike single-round exchange models, real-world trade typically involves ‘RepeatedInteraction’ between parties over time. This ongoing interaction allows agents to observe the outcomes of previous transactions and adjust their strategies accordingly. Such learning and adaptation can take the form of refining valuation functions, improving negotiation tactics, or building trust to facilitate future exchanges. The capacity for repeated interactions fundamentally alters the strategic landscape, enabling mechanisms like reputation building and the enforcement of implicit or explicit contracts that are not possible in one-time interactions. This dynamic necessitates algorithms capable of modeling and responding to evolving agent behavior and preferences.

The budget constraint is a fundamental requirement in any economic exchange, dictating that a seller’s revenue from a transaction must be greater than or equal to their associated costs. This ensures the seller does not incur a loss and provides an incentive to participate in the trade. The cost calculation incorporates not only direct production or acquisition costs, but also opportunity costs – the value of the next best alternative use of the seller’s resources. Failure to meet this constraint would result in a net loss for the seller, creating an unsustainable trading scenario and ultimately hindering market participation. Therefore, any algorithmic trading model must explicitly account for and enforce this budget constraint to ensure viable and consistent operation.

The budget constraint in a trading scenario is not monolithic, but rather exists along a spectrum of balance requirements. A ‘WeakBudgetBalance’ dictates only that the seller’s revenue must be greater than or equal to their cost – revenue \geq cost – allowing for potential surplus. Conversely, a ‘StrongBudgetBalance’ enforces a strict equality between payment and the seller’s valuation of the good – payment = valuation – eliminating any profit margin. This distinction is critical for algorithm design; algorithms designed for weak budget balance can prioritize maximizing surplus, while those operating under strong budget balance must prioritize finding a mutually acceptable valuation and avoid overcharging, impacting negotiation strategies and potential trade frequency.

Algorithmic Strategies: Optimizing for Regret and Profit

Regret minimization is a core algorithmic strategy used in automated trading systems to optimize performance over a series of decisions. The principle centers on reducing the cumulative difference – the ‘regret’ – between the rewards achieved by the algorithm and the rewards that would have been obtained by consistently selecting the optimal action at each step. This is not necessarily about achieving the highest possible reward on any single trade, but rather about minimizing the lost opportunity cost over the long term. Algorithms employing regret minimization techniques often utilize strategies that balance exploration of potentially better options with exploitation of currently known profitable strategies, adapting their behavior based on observed rewards and aiming to converge towards a near-optimal policy. The goal is to ensure that, over time, the algorithm’s cumulative reward approaches the maximum possible reward, thereby minimizing the accumulated regret.

ProfitMaximization, as a core algorithmic strategy, centers on identifying and executing trades that yield the highest cumulative profit over a defined period. This is achieved through continuous evaluation of potential trade outcomes, factoring in costs such as transaction fees and slippage, and prioritizing actions with the greatest expected return. Algorithms employing ProfitMaximization often utilize historical data and real-time market information to forecast price movements and optimize trade timing. The objective function typically involves summing the profits from each successful trade, less any associated costs, with the algorithm aiming to find the trade sequence that maximizes this sum. \text{Total Profit} = \sum_{i=1}^{n} (P_i - C_i) , where P_i is the profit from trade i and C_i represents the costs associated with that trade.

The UCBAlgorithm, a common approach in automated trading, operates by strategically balancing exploration and exploitation when determining optimal pricing. This is achieved through the maintenance of a DistributionOverPrices, which represents the algorithm’s belief about the potential profitability of various price points. Exploration involves testing prices with high uncertainty, even if their current estimated reward is low, to refine the DistributionOverPrices. Conversely, exploitation focuses on selecting prices currently believed to yield the highest reward, based on the algorithm’s existing knowledge. The UCBAlgorithm specifically uses an upper confidence bound to quantify this trade-off; prices are selected not just for their average estimated reward, but also for the degree of uncertainty associated with that estimate, encouraging continued investigation of potentially valuable, but currently under-sampled, price levels.

Navigating Uncertainty: Stochasticity and Adversarial Environments

Financial markets inherently operate within a StochasticEnvironment, meaning outcomes are probabilistic rather than deterministic. This randomness stems from numerous factors including unpredictable order flow, news events, and macroeconomic indicators. Consequently, any trading strategy’s performance is not a fixed value, but rather a random variable with an associated probability distribution. This necessitates the use of statistical analysis and risk management techniques to quantify potential gains and losses, and to assess the expected value of any trading opportunity. The presence of stochasticity also limits the ability to predict future market behavior with certainty, requiring algorithms to adapt to changing conditions and manage inherent uncertainty.

Adversarial environments represent a specific class of challenges for algorithmic design, differing from stochasticity through intentionality. In these environments, the external forces are not simply random but actively manipulate inputs to degrade algorithm performance; this contrasts with stochastic environments where outcomes are probabilistic but not directed against the algorithm. This active manipulation necessitates algorithms capable of anticipating and mitigating worst-case scenarios, rather than simply averaging performance across a probability distribution. The presence of an adversarial agent introduces a game-theoretic element, requiring algorithms to consider the strategic implications of their actions and the potential responses of the environment. Consequently, performance evaluation in adversarial environments often focuses on minimax regret or worst-case guarantees, rather than expected performance metrics.

Acknowledging stochastic and adversarial elements within an operational environment is fundamental to algorithm development and performance analysis. Robust algorithms must be designed to function effectively despite inherent randomness and potential malicious manipulation of input data or environmental conditions. Furthermore, a clear understanding of these factors enables the derivation of theoretical lower bounds on achievable performance; these bounds represent the best possible outcome any algorithm could attain given the constraints imposed by the environment. Establishing such bounds is critical for evaluating algorithm efficiency and identifying areas for improvement, as it provides a benchmark against which algorithmic performance can be measured and compared.

Ensuring Long-Term Viability: The Importance of Global Budget Balance

The sustained performance of any algorithmic trading strategy fundamentally relies on maintaining ‘Global Budget Balance’ – a critical condition where cumulative profits remain non-negative over the duration of operation. This principle dictates that, while individual trades may result in losses, the algorithm must consistently generate enough profit to offset these losses and avoid eventual financial depletion. Without this budgetary control, even algorithms demonstrating short-term gains are destined to fail in the long run, highlighting its importance as a foundational requirement for viable automated trading systems. Ensuring this balance isn’t simply about avoiding net losses; it’s about establishing a robust and sustainable framework for continuous operation and predictable financial outcomes.

Maintaining budgetary control within automated trading systems frequently leverages mechanisms like the ‘FixedPriceMechanism’, which operates on the principle of establishing a predefined ‘DistributionOverPrices’. This approach doesn’t simply set a static price; instead, it defines a probability distribution encompassing potential transaction prices. By sampling from this distribution for each trade, the algorithm inherently manages its financial exposure. A well-defined distribution is crucial, as it dictates the likelihood of profitable versus loss-making trades, directly impacting the cumulative profit over time. This probabilistic pricing strategy allows for a balance between attracting trades and ensuring the algorithm doesn’t systematically lose money, forming a cornerstone of long-term viability in online bilateral trade scenarios and enabling the achievement of optimal regret bounds, such as O(T^(3/4)).

The research establishes a critical performance benchmark for online bilateral trade algorithms operating under Global Budget Balance (GBB). By leveraging bounded density assumptions, the study demonstrates that an algorithm employing a GBB fixed distribution over prices can achieve a regret bound of O(T^{3/4}). This result is significant because it matches the performance of traditional fixed-price mechanisms, proving that budgetary control doesn’t necessitate a trade-off in efficiency. The findings effectively establish a tight bound – meaning further improvements in regret minimization under these conditions are unlikely – and validate the viability of GBB as a robust strategy for long-term algorithmic trading success, confirming that maintaining non-negative cumulative profits doesn’t compromise competitive performance.

The pursuit of robust algorithms in stochastic environments, as detailed in this work, echoes a fundamental tenet of systems design: interconnectedness. This paper demonstrates how a carefully constructed algorithm, balancing exploration and exploitation, achieves near-optimal regret even with unpredictable price fluctuations. It’s akin to understanding the entire circulatory system before attempting a heart transplant-a single adjustment necessitates comprehension of the whole. As Barbara Liskov aptly stated, “It’s one of the most powerful concepts in programming – that you can build abstractions on top of abstractions.” This principle is clearly visible in the layered approach to regret minimization presented, building upon established bandit algorithms to create a more resilient system for online bilateral trade.

What Lies Ahead?

This work establishes a firmer foundation for modeling bilateral trade, shifting focus from the brittle concept of a single, optimal price to the more realistic landscape of price distributions. However, the elegance of this approach reveals the inherent limitations of current regret minimization frameworks. The bounded density assumption, while simplifying analysis, represents a significant constraint – real-world price discovery rarely adheres to such neat boundaries. Future iterations must grapple with unbounded or poorly characterized distributions, perhaps through adaptive density estimation or the incorporation of prior knowledge.

The analogy to urban planning feels apt. This algorithm represents a thoughtful renovation of existing infrastructure, optimizing flow within established constraints. But a truly robust system requires the capacity for organic growth. The next challenge lies in developing algorithms that can dynamically adjust their exploration-exploitation balance, not simply in response to observed data, but in anticipation of shifting environmental conditions. A static blueprint, however refined, will inevitably crumble under the weight of unforeseen circumstances.

Ultimately, the field needs to move beyond simply minimizing regret. The goal isn’t merely to avoid bad trades, but to cultivate mutually beneficial exchanges. This necessitates a deeper investigation into the structural properties of trade itself – the networks of relationships, the asymmetries of information, and the complex interplay of incentives. A truly intelligent system will not just react to the market; it will shape it.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05681.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Top 15 Insanely Popular Android Games

- EUR UAH PREDICTION

- Did Alan Cumming Reveal Comic-Accurate Costume for AVENGERS: DOOMSDAY?

- 4 Reasons to Buy Interactive Brokers Stock Like There’s No Tomorrow

- Silver Rate Forecast

- DOT PREDICTION. DOT cryptocurrency

- ELESTRALS AWAKENED Blends Mythology and POKÉMON (Exclusive Look)

- New ‘Donkey Kong’ Movie Reportedly in the Works with Possible Release Date

- Core Scientific’s Merger Meltdown: A Gogolian Tale

2026-02-08 18:32