For sixteen years now-since the Great Recession’s ignominious end-the S&P 500, Dow Jones, and Nasdaq Composite have trudged forward like a pack of overfed spaniels, blissfully unaware of the leash of gravity. Even after a brief bout of springtime jitters, these indices have resumed their march toward record highs, buoyed by the latest fads: artificial intelligence, interest rate optimism, and the vague promise that tariffs will one day cease to exist.

Yet as prices rise, so too does the scent of hubris. By one measure-a peculiar alchemy of earnings and time-the stock market stands as the second-most-expensive in 154 years. Historically, such exuberance has always been followed by a comedown. But some analysts, with the moral certainty of a man who’s just won a bet on a horse named “Sure Thing,” insist this is merely “the new normal.” A comforting delusion, one might say, if only it weren’t so costly.

A New Normal? Perhaps, but Not for the Reasons You Suspect

Last week, Savita Subramanian of Bank of America declared in a note to clients that we should “anchor to today’s multiples as the new normal” rather than “expect mean reversion to a bygone era.” A bold pronouncement, delivered with the gravitas of a man who’s forgotten his umbrella in a thunderstorm. Her rationale? The “rapid growth” of AI and the “resilient earnings” of the Magnificent Seven. One might as well argue that a house built on sand deserves a plaque for architectural innovation.

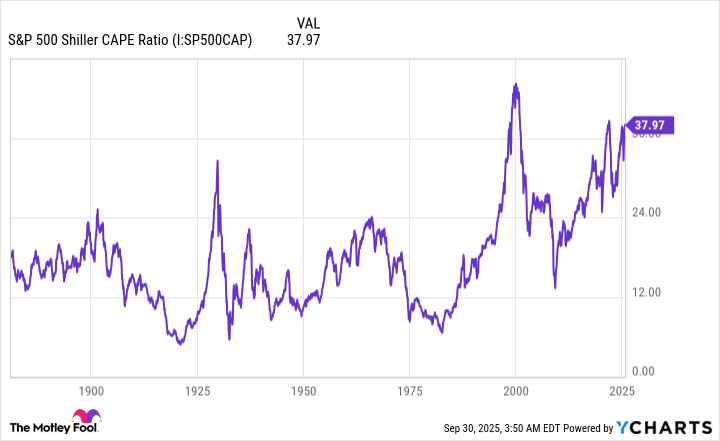

Subramanian is not alone. Other analysts, like so many financial alchemists, insist the seven-headed beast of tech is proof that valuations are merely “reasonable.” Yet history, that most stubborn of narrators, tells a different tale. Consider the Shiller P/E Ratio-a curious beast that adjusts earnings for the cyclical whims of the economy. From 1871 to 1995, it wandered between 10 and 20. Now, it lingers between 20 and 30, a range once reserved for the fever dreams of tulip mania.

The “new normal” did not begin with AI. It began in the mid-1990s, when the internet-our modern-day printing press-democratized information and turned Main Street into a Wall Street sideshow. Suddenly, every man and his dog could access balance sheets at the click of a button. Interest rates, meanwhile, fell like a deflated balloon, allowing companies to borrow cheaply and spend extravagantly.

AI, then, is not the cause of inflated valuations but the latest prop in a long-running farce. The real architects of this new normal are the same forces that have always lurked in the shadows: liquidity, leverage, and the human tendency to believe that this time, truly, it is different.

This Is the Second-Priciest Stock Market in Over 150 Years

To claim the Shiller P/E is a perfect predictor would be to mistake a compass for a map. Yet its track record is troubling. Since 1871, the ratio has exceeded 30 on six occasions. Each was followed by a collapse of 20% or more. The first, in 1929, preceded the Great Depression. The second, in 1999, heralded the dot-com implosion. The third, in 2018, foreshadowed a 20% plunge. The fourth, in 2020, coincided with the pandemic crash. The fifth, in 2022, marked the start of a bear market. And the sixth? It is ongoing, with the ratio now at 40.15.

These are not mere numbers; they are the ghosts of past excesses, whispering warnings in the ears of the present. The Shiller P/E is not a crystal ball, but a rearview mirror. And what it reflects is a pattern as old as capitalism itself: greed, followed by fear, followed by a reckoning.

Consider the “next-big-thing” trends of the past three decades. The internet, blockchain, AI-each has been hailed as a revolution, only to be met with the same cycle of hype and disillusionment. Investors, like children at a candy store, have consistently overestimated the utility of these innovations. AI, for all its promise, remains a box of chocolates: you never know what you’re gonna get.

Loading…

–

Though we’ve lived in this “new normal” since the 1990s, there is little question that stocks are now priced with the optimism of a man who’s just sold his car for a goat. History, that relentless pedant, reminds us that anchoring to such valuations is a fool’s errand. The market is not a machine; it is a theater of human folly, where the final act is always the same: the curtain falls, the lights dim, and the audience is left to count the coins in their pockets.

And yet, the performance continues. The music plays on.

Read More

- 21 Movies Filmed in Real Abandoned Locations

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- The 11 Elden Ring: Nightreign DLC features that would surprise and delight the biggest FromSoftware fans

- 10 Hulu Originals You’re Missing Out On

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- 20 Films Where the Opening Credits Play Over a Single Continuous Shot

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Top ETFs for Now: A Portfolio Manager’s Wry Take

- 🚨 Kiyosaki’s Doomsday Dance: Bitcoin, Bubbles, and the End of Fake Money? 🚨

- Crypto’s Comeback? $5.5B Sell-Off Fails to Dampen Enthusiasm!

2025-10-03 10:18