Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new analysis reveals that scrutinizing the final stages of image generation processes can reliably identify pictures created by artificial intelligence.

This research demonstrates a generalizable method for detecting AI-generated images by analyzing the unique characteristics of the final component within generator architectures like diffusion models and VAE decoders.

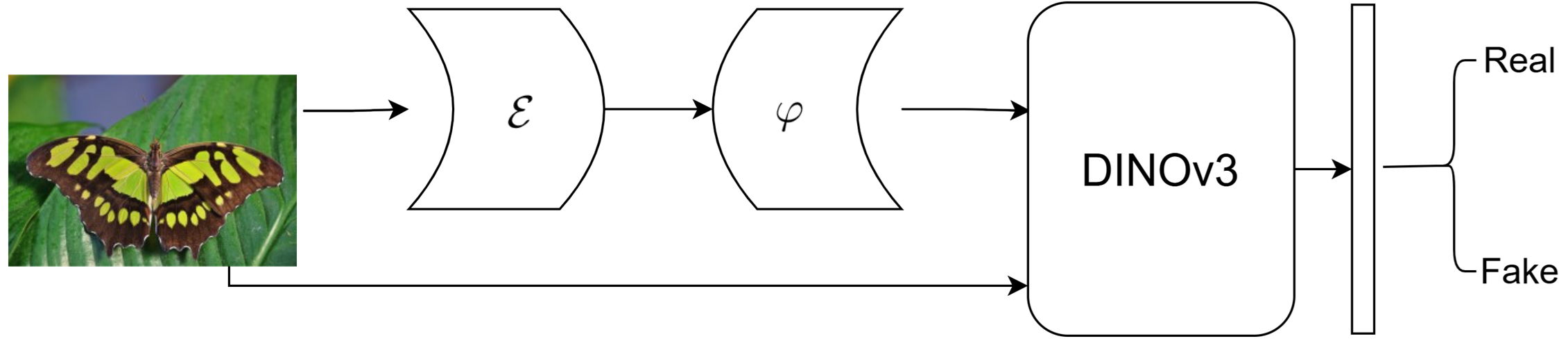

Despite advancements in deepfake detection, current methods struggle to generalize across diverse image generation models. This limitation motivates our work, ‘Exploiting the Final Component of Generator Architectures for AI-Generated Image Detection’, which proposes a novel approach centered on the shared architectural characteristics of modern generators. We demonstrate that by “contaminating” real images with the final component of a generator and training a detector to distinguish them, we can achieve remarkably generalizable detection capabilities. This allows for accurate identification of AI-generated images even from previously unseen generators-but can this approach be extended to detect manipulations beyond purely synthetic images?

Unveiling the Patterns of Synthetic Imagery

The digital landscape is rapidly being reshaped by the increasing prevalence of synthetic imagery. Driven by remarkable progress in generative models – algorithms capable of creating photorealistic images from scratch – the sheer volume of AI-generated content is expanding exponentially. This proliferation presents a significant challenge, as distinguishing between authentic photographs and convincingly fabricated ones becomes increasingly difficult. Consequently, a critical need has emerged for robust detection methods capable of identifying synthetic images, safeguarding the integrity of visual information, and mitigating the potential for misinformation and manipulation across diverse digital platforms. The development of such techniques is no longer simply a matter of academic curiosity, but a practical imperative for maintaining trust in a visually-saturated world.

Conventional image forensics, historically reliant on detecting subtle inconsistencies introduced by image manipulation – such as JPEG compression artifacts or sensor noise – are increasingly ineffective against the sophisticated outputs of modern generative models. These AI systems, capable of producing photorealistic images with meticulously crafted details and a lack of typical manipulation traces, present a significant challenge to established detection techniques. The resulting vulnerability extends beyond simple misinformation; manipulated imagery can erode trust in visual evidence, impact legal proceedings, and destabilize public discourse. As synthetic content becomes increasingly pervasive and indistinguishable from reality, the limitations of traditional methods highlight an urgent need for novel approaches capable of discerning authentic imagery from AI-generated fabrication, safeguarding the integrity of digital spaces.

The advancement of synthetic imagery relies heavily on extensive datasets like MS-COCO, a resource providing millions of labeled images crucial for training generative models to convincingly replicate real-world scenes. However, this same dataset is equally vital for rigorously testing the efficacy of detection methods designed to distinguish between authentic and artificially created visuals. As generative models improve their ability to mimic reality – often achieving performance benchmarks on MS-COCO – the demand for increasingly sophisticated detection techniques escalates. This creates a cyclical need: better datasets fuel better generation, which in turn necessitates more robust detection algorithms, pushing the boundaries of both artificial intelligence and digital forensics. The continuous refinement of these models and detectors, benchmarked against datasets like MS-COCO, is therefore paramount in navigating an increasingly complex digital landscape where visual authenticity is constantly challenged.

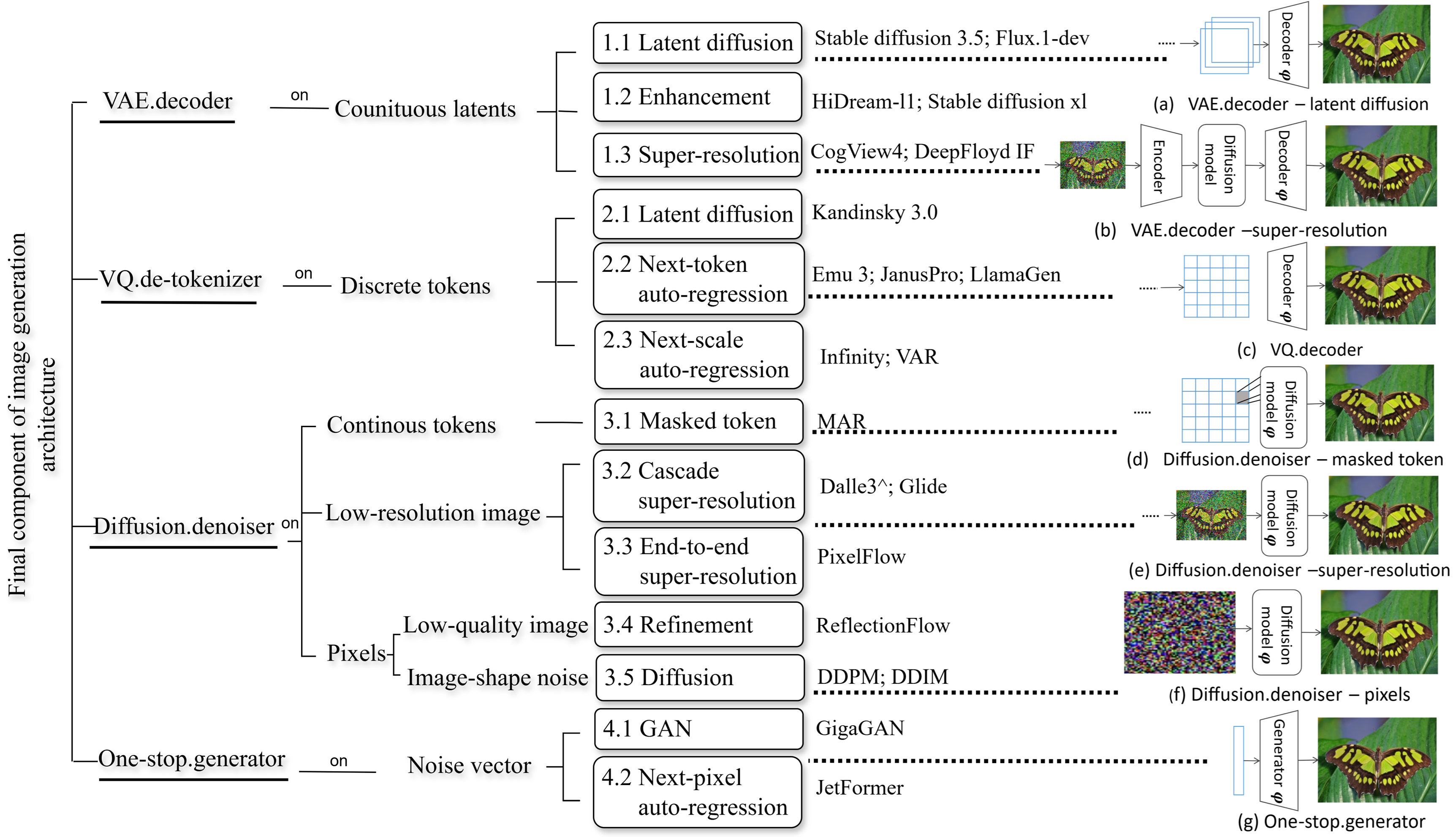

Deconstructing Generative Architectures: Identifying Algorithmic Signatures

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), Diffusion Models, and Autoregressive Models each exhibit distinct statistical properties in their outputs due to fundamental differences in their training and operational mechanisms. GANs, trained through adversarial processes, often introduce high-frequency artifacts and mode collapse, resulting in images with limited diversity and potential checkerboard patterns. Diffusion Models, relying on iterative denoising, tend to produce images with higher perceptual quality but may exhibit a characteristic smoothness or lack of fine detail. Autoregressive models, generating images pixel by pixel, can introduce directional dependencies and noticeable correlations between adjacent pixels. These inherent characteristics, manifesting as specific patterns in the frequency domain, color spaces, or pixel-level statistics, serve as detectable ‘fingerprints’ allowing for the differentiation of images originating from different generative architectures.

The final component of a generative model-such as a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) decoder, a super-resolution diffusion model, or a Vector Quantized (VQ) de-tokenizer-imposes specific constraints and biases on the generated output. These components are responsible for translating a latent representation into the final image or data format, and their inherent limitations manifest as detectable artifacts. For instance, VAE decoders may introduce blurring due to the reconstruction loss, super-resolution diffusers can exhibit characteristic frequency domain patterns, and VQ de-tokenizers introduce grid-like structures arising from the discrete latent space. These outputs are not random; they are systematically influenced by the algorithmic properties and parameters of the final component, creating unique, model-specific characteristics that can be leveraged for detection.

The development of a ‘Trace Space’ relies on characterizing the specific outputs and behaviors of the Final Component within each generative model. This involves analyzing quantifiable metrics such as the component’s frequency response, the statistical distribution of its outputs, and the presence of unique artifacts introduced during the final image construction process. For example, VAE Decoders often exhibit characteristics related to Gaussian blurring, while Super-Resolution Diffusers may introduce specific patterns dependent on the diffusion kernel used. By isolating and cataloging these component-specific features – including spectral signatures, pixel-level statistics, and the types of introduced noise – a multi-dimensional ‘Trace Space’ can be constructed. This space serves as a feature vector, allowing for the differentiation of images generated by distinct architectures and providing a basis for automated detection methods.

Zero-Shot Detection: A Strategy for Generalization

Effective zero-shot detection is predicated on the quality of feature extraction, and current implementations commonly utilize pretrained visual backbones such as DINOv3. These backbones, trained on extensive datasets for tasks like image classification and self-supervised learning, provide a strong foundation for representing visual information in a high-dimensional feature space. DINOv3, specifically, is a self-supervised vision transformer known for its robust feature representations and transferability. By leveraging these pretrained weights, the zero-shot detection system avoids the need for task-specific training data, enabling it to generalize to unseen classes and scenarios. The extracted features serve as the input for subsequent clustering and classification stages, and the performance of these stages is directly correlated with the quality and discriminative power of the features generated by the backbone network.

K-Medoids clustering is utilized as a sampling strategy to address the computational demands of training a zero-shot detection model on a large and potentially unbounded feature space. Instead of processing all extracted features, K-Medoids identifies a set of k representative samples – medoids – by minimizing the sum of distances between each data point and its nearest medoid. These medoids act as prototypes, effectively reducing the dataset size while preserving its essential characteristics. This sampled subset is then used for training, significantly improving computational efficiency and reducing memory requirements without substantial performance degradation. The selection of k is a hyperparameter, influencing the granularity of representation and impacting the trade-off between training speed and accuracy.

Following feature extraction and clustering, a binary classification model is utilized to differentiate between real and AI-generated images. This classifier is trained using Cross-Entropy Loss, a standard loss function for binary classification tasks that quantifies the difference between the predicted probability distribution and the true label (real or AI-generated). The extracted features from the clustered data serve as input to the classifier, enabling it to learn a decision boundary that effectively separates the two image types. The model aims to minimize the loss, thereby maximizing the accuracy of its predictions on unseen images, and ultimately determining the origin – real or AI-generated – of a given input.

Evaluating Performance and Considering Broader Implications

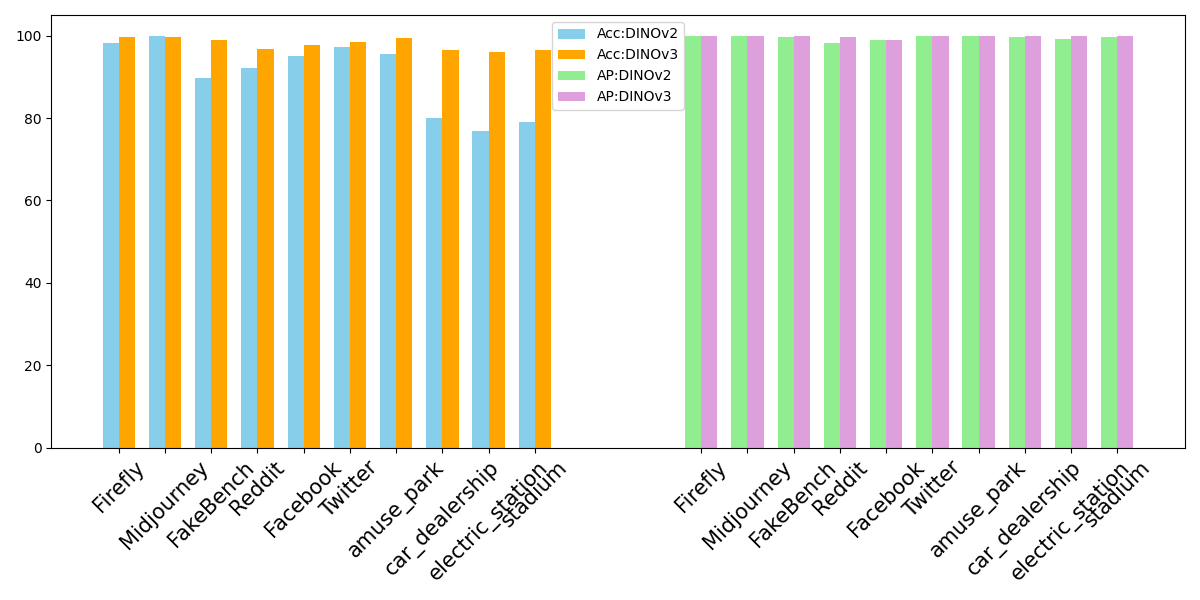

Rigorous evaluation of the AI-generated image detector relied on established computer vision metrics, notably Average Precision and Detection Accuracy. Average Precision, a comprehensive measure of both precision and recall across varying confidence thresholds, gauged the detector’s ability to accurately identify generated images while minimizing false positives. Simultaneously, Detection Accuracy provided a straightforward assessment of the overall correctness of the detector’s classifications. These metrics, calculated across diverse datasets and generative models, facilitated a quantitative understanding of the detector’s performance and allowed for direct comparison against existing state-of-the-art methods, ultimately demonstrating its reliability in distinguishing between authentic and synthetically created visual content.

The developed image detection system exhibits remarkable accuracy in discerning AI-generated content, reaching up to 99.22% in evaluations. This level of performance represents a significant advancement over previous methods, specifically a 2% improvement when contrasted with pairwise training techniques. Such heightened precision isn’t merely a numerical increase; it suggests a more robust and reliable system capable of effectively identifying synthetic images. The gains achieved demonstrate the efficacy of the adopted approach, potentially enabling more accurate content authentication and bolstering efforts to combat the spread of misinformation facilitated by increasingly sophisticated image generation technologies.

The developed image detector exhibits remarkable robustness, consistently surpassing the performance of established baseline methods across a spectrum of evaluation benchmarks. Crucially, this detector doesn’t merely identify images from generators it was explicitly trained on; it demonstrates strong generalization capabilities, accurately discerning AI-generated content even when presented with images created by generators that have undergone fine-tuning or represent entirely new architectures. This sustained high Average Precision – a metric reflecting the detector’s ability to avoid false positives – highlights its adaptability and suggests a fundamental ability to recognize the inherent statistical fingerprints of AI image synthesis, rather than simply memorizing specific generator outputs. Such generalization is vital for real-world deployment, where the landscape of image generators is constantly evolving and the detector must remain effective against unseen techniques.

The study highlights a crucial aspect of understanding generative models: the final component often betrays the artificiality of the creation. This aligns with Fei-Fei Li’s observation that, “AI is not about replacing humans; it’s about augmenting human capabilities.” By focusing on the ‘trace’ left in the final stages of image generation – whether a diffusion model or a VAE decoder – researchers aren’t attempting to mimic human creativity, but rather to develop a robust method for discerning machine-made content. The ability to reliably identify these traces provides a valuable tool for maintaining trust in visual information, augmenting human perception with algorithmic precision, and offering a generalizable approach, independent of the specific generative architecture employed.

What Lies Ahead?

The demonstrated efficacy of analyzing generator architectures’ final components suggests a shift in focus for detection methodologies. Rather than endlessly chasing artifacts within generated images-a perpetual arms race against increasingly sophisticated diffusion models and VAE decoders-attention may be more fruitfully directed towards the inherent constraints of the generative process itself. The current work offers a promising, model-agnostic pathway, but relies on access to, and analysis of, these final components – a constraint that may not always be practical in real-world scenarios.

A logical extension of this research lies in exploring whether these inherent ‘traces’ can be detected indirectly, perhaps through subtle statistical anomalies in the generated imagery that correlate with the generator’s internal structure. The challenge, of course, is disentangling these signals from the noise of artistic variation and intentional manipulation. It’s a pattern recognition problem, naturally, and one that demands a deeper understanding of the information bottleneck created by any generative process.

Ultimately, the field may need to accept a fundamental truth: perfect detection is likely unattainable. The pursuit, however, isn’t about achieving absolute certainty, but rather about continually refining the signal-to-noise ratio. A robust detection system, built on understanding generative constraints, offers not a definitive answer, but a more informed, and adaptable, assessment of authenticity.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.20461.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Building 3D Worlds from Words: Is Reinforcement Learning the Key?

- The Best Directors of 2025

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Mel Gibson, 69, and Rosalind Ross, 35, Call It Quits After Nearly a Decade: “It’s Sad To End This Chapter in our Lives”

- 20 Best TV Shows Featuring All-White Casts You Should See

- Umamusume: Gold Ship build guide

- Top 20 Educational Video Games

- Most Famous Richards in the World

- Celebs Who Married for Green Cards and Divorced Fast

2026-01-29 21:15