Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new framework is emerging that harnesses the power of predictive models to unlock more reliable insights from incomplete data.

This review examines Prediction-Powered Inference, detailing its theoretical underpinnings, practical applications, and advantages over conventional methods for handling missing data and achieving semiparametric efficiency.

Increasingly, researchers leverage machine learning predictions to address incomplete data, yet treating these predictions as ground truth introduces bias while ignoring them forfeits valuable information. This challenge is addressed in ‘Demystifying Prediction Powered Inference’, which synthesizes a principled framework-Prediction-Powered Inference (PPI)-for improving statistical efficiency via predictions from large unlabeled datasets, while maintaining valid inference through explicit bias correction. The paper demonstrates that responsible application of PPI requires careful consideration of underlying assumptions and potential pitfalls like double-dipping, and provides a practical workflow alongside diagnostic tools for implementation. Will this unified approach enable broader, more reliable integration of machine learning predictions into rigorous scientific inference?

Decoding the Silence: The Perils of Missing Data

Complete Case Analysis, a historically common statistical practice, operates by eliminating any observation containing even a single missing data point. While seemingly straightforward, this approach can dramatically reduce sample size, potentially discarding a substantial portion of collected information. This data loss isn’t merely a matter of statistical power; if the missingness isn’t entirely random – a scenario frequently encountered in real-world datasets – the remaining complete cases may no longer accurately represent the original population. Consequently, analyses based solely on complete cases risk producing biased parameter estimates and inaccurate inferences, undermining the validity of research findings and potentially leading to flawed conclusions. The efficiency of the analysis is also compromised, as the precision of estimates decreases with smaller sample sizes, requiring larger effects to be detected with the same level of confidence.

The prevalence of missing data presents a significant hurdle in contemporary statistical analysis, particularly as datasets grow in complexity and scope. Modern data collection, whether through large-scale surveys, sensor networks, or electronic health records, frequently encounters incomplete information – a departure from the ideal of complete datasets. Crucially, the assumption of Missing Completely At Random (MCAR) – where the probability of a value being missing is unrelated to both observed and unobserved variables – is rarely met in practice. This means missingness is often not random; it can be linked to the very characteristics researchers aim to study, introducing bias if ignored. Consequently, traditional methods that simply exclude incomplete cases can severely limit statistical power and yield misleading conclusions, necessitating more sophisticated techniques capable of addressing these non-random patterns of missing data.

The increasing prevalence of missing data in contemporary research necessitates a shift beyond traditional statistical methods. While techniques like Complete Case Analysis offer simplicity, their reliance on complete datasets often discards substantial amounts of potentially valuable information, introducing bias and reducing statistical power. Modern approaches prioritize maximizing data utilization through techniques such as multiple imputation and full information maximum likelihood estimation, which aim to fill in missing values or incorporate incomplete cases directly into the analysis. These robust alternatives allow researchers to draw more accurate and reliable inferences, particularly when data is not missing completely at random – a common scenario in fields ranging from healthcare and social sciences to environmental monitoring and beyond. Ultimately, embracing these flexible methodologies represents a crucial step toward unlocking the full potential of available data and advancing scientific understanding.

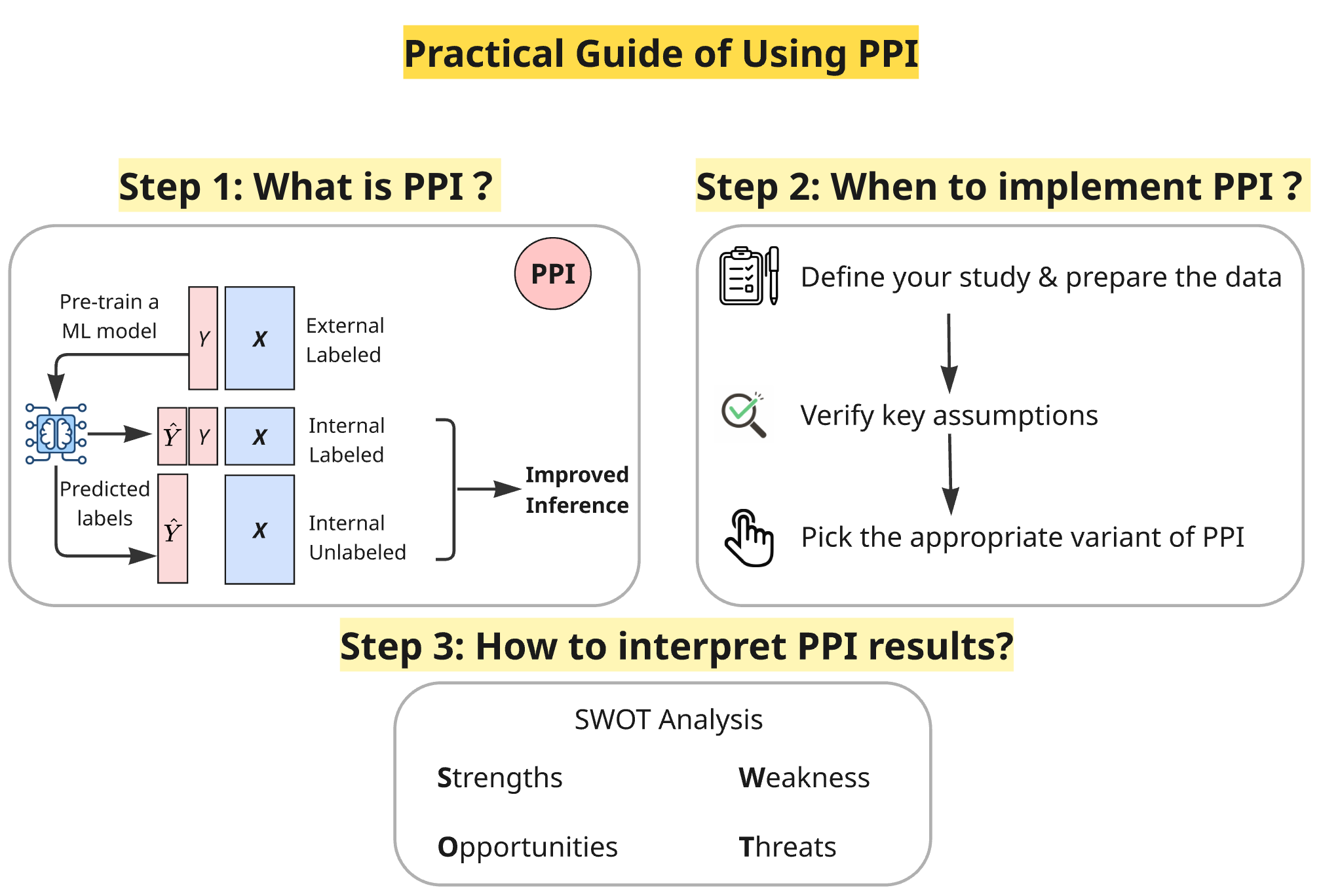

Reconstructing Reality: Prediction-Powered Inference

Prediction-Powered Inference (PPI) addresses the challenge of incorporating unlabeled data into statistical analyses by utilizing a Prediction Model to estimate missing values. This approach differs from traditional methods by explicitly modeling the data-generating process to impute missing information. The Prediction Model, trained on observed data, generates predictions for unlabeled instances, effectively expanding the dataset. These predictions are then integrated with the observed data to create an augmented dataset suitable for inference. The core principle is to leverage the predictive power of machine learning algorithms to reduce bias and improve the efficiency of statistical estimation when dealing with incomplete data.

Prediction-Powered Inference (PPI) operates by integrating predictions generated from unlabeled data with the existing observed data to create an augmented dataset. This combination isn’t a simple concatenation; rather, predicted values for missing data points are weighted and incorporated into the analysis alongside directly observed values. The effect of this augmentation is a reduction in bias stemming from the original, potentially limited, observed dataset. By leveraging the broader distribution represented in the unlabeled data – even through an imperfect predictive model – PPI effectively increases the sample size and improves the representativeness of the data used for statistical inference. This process allows for more robust estimates and reduces the impact of selection bias or missing data patterns present in the originally observed data.

Statistical inference using Prediction-Powered Inference (PPI) necessitates bias correction due to the inherent imperfections of the prediction model used to impute missing data. Without correction, the combined observed and predicted data will exhibit a systematic bias, leading to inaccurate estimates of population parameters and inflated Type I error rates. Bias correction techniques operate by adjusting the predicted values-or the associated weights-to account for the expected difference between the predicted values and the true, unobserved values. These adjustments are typically derived from properties of the prediction model, such as its training data or its functional form, and aim to minimize the expected discrepancy between the prediction and the true value in the population. The effectiveness of these corrections directly impacts the validity of downstream statistical analyses performed on the augmented dataset.

Testing the Boundaries: Assumptions and Robustness

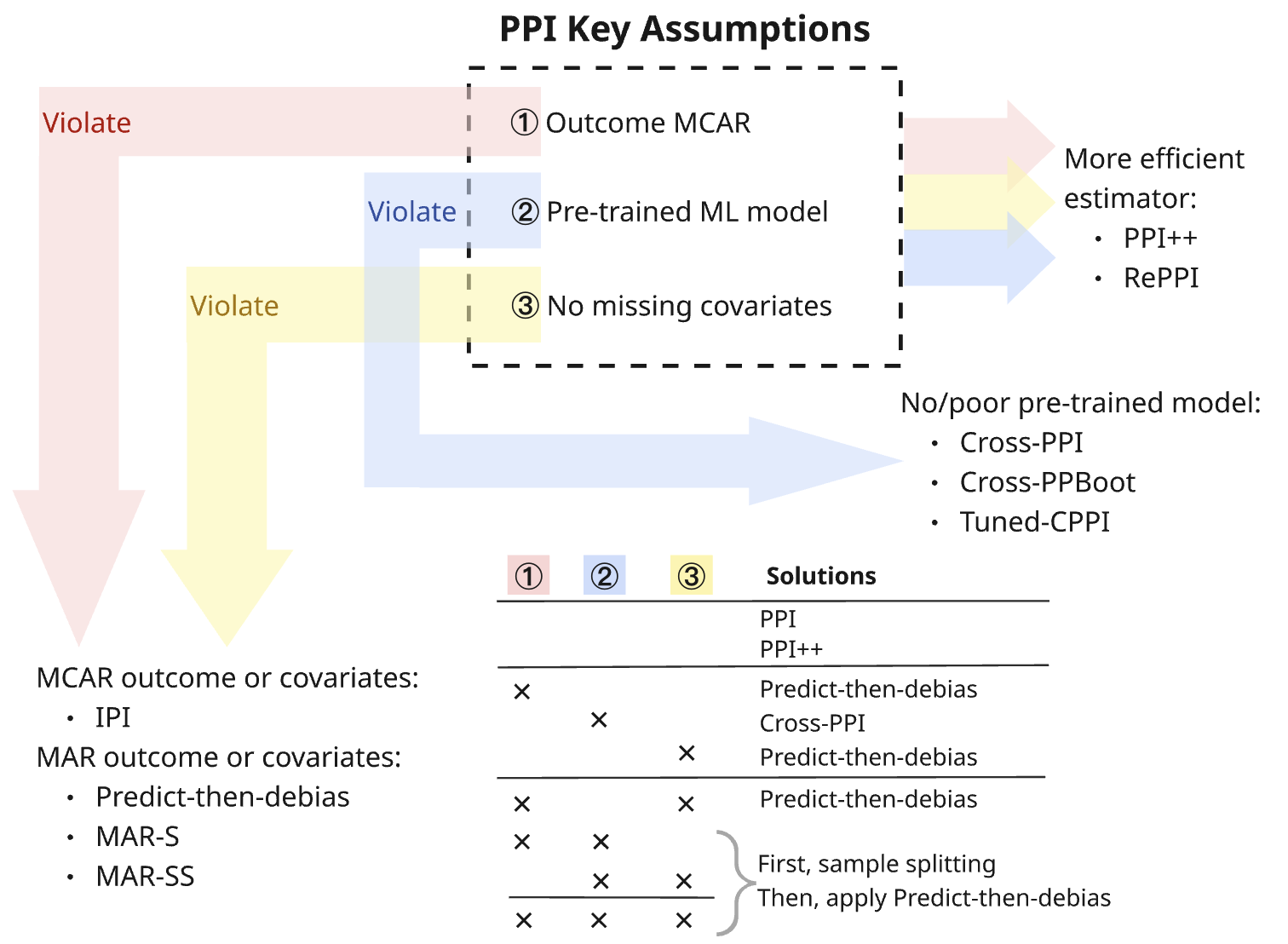

The validity of Prediction-based Inference (PPI) fundamentally depends on satisfying key assumptions, notably the Positivity Condition. This condition requires sufficient overlap in characteristics between treated and control units across all subgroups defined by covariates; specifically, for every combination of covariate values, there must be individuals in both the treated and control groups. Failure to meet the Positivity Condition – resulting in a lack of comparable individuals – introduces bias into the estimation of treatment effects, as the model is forced to extrapolate beyond the observed data. Assessing the Positivity Condition typically involves examining the distribution of covariates within each treatment group and identifying regions where overlap is limited, potentially necessitating data trimming, weighting adjustments, or alternative modeling strategies.

Sensitivity analysis is a critical component of Propensity Score-based inference, employed to evaluate the stability of results when underlying assumptions are not fully met. This process involves systematically altering key assumptions – such as those related to covariate balance or model specification – and observing the resultant impact on estimated treatment effects. Specifically, researchers may introduce varying degrees of unmeasured confounding or assess the influence of different functional forms for the propensity score model. The magnitude of change in effect estimates following these alterations indicates the robustness of the findings; smaller changes suggest greater reliability, while substantial shifts necessitate cautious interpretation and further investigation into potential biases. This analysis doesn’t aim to correct for violations, but rather to quantify the potential magnitude of bias and inform the user about the limitations of the inference.

CrossFitting is a statistical technique employed to mitigate overfitting and maintain the validity of inferences when utilizing complex prediction models. This method involves repeatedly estimating parameters using different subsets of the data, effectively creating multiple estimation procedures. PPI (Prediction-based Inference) and PPI++ leverage CrossFitting to achieve more precise estimates, consistently demonstrating narrower confidence intervals compared to traditional complete-case analysis, but only when the predictive performance of the model meets a sufficient quality threshold. The reduction in variance afforded by CrossFitting allows for more efficient statistical inference in high-dimensional settings where standard methods may struggle.

Beyond the Horizon: Applications and Future Directions

Probabilistic Prediction Intervals (PPI) demonstrate notable adaptability to contemporary data science challenges, notably within the realm of Federated Inference. This distributed machine learning approach allows for model training and analysis across multiple decentralized datasets – such as those held by individual hospitals or mobile devices – without requiring the sensitive raw data to be transferred or centrally stored. PPI facilitates this privacy-preserving analysis by enabling the quantification of uncertainty directly at each data source, and then aggregating these local predictions to generate global inferences. This capability is crucial for applications where data governance and user privacy are paramount, effectively unlocking insights from distributed data silos while upholding stringent security standards and regulatory compliance.

Probabilistic Power Inference (PPI) isn’t simply a static analytical tool; the framework actively facilitates informed data acquisition through techniques like Active Inference. This advanced approach moves beyond passive observation by strategically selecting which data points require labeling, prioritizing those that will yield the greatest improvement in model accuracy and efficiency. Rather than randomly requesting labels, Active Inference within PPI identifies the most informative samples-those that, when added to the training set, will most effectively reduce uncertainty and refine the inference process. This targeted labeling strategy not only accelerates the learning process but also minimizes the need for extensive, costly, and time-consuming data annotation, ultimately making robust inference attainable even with limited labeled data.

Recent refinements to the Propensity-score-based Post-Inference (PPI) framework, notably through Doubly Robust and Model Assisted Estimation techniques, demonstrably improve the reliability and accuracy of data analysis. Studies reveal that PPI and its enhanced version, PPI++, consistently achieve coverage rates near the expected 90% when underlying assumptions are satisfied, a performance significantly exceeding methods susceptible to ‘double-dipping’-a statistical pitfall that compromises validity. However, investigations also pinpoint a critical limitation: all PPI-based approaches, alongside traditional statistical methods, falter when data exhibits Missing Not At Random (MNAR) characteristics-situations where the absence of data is linked to unobserved outcomes-underscoring the importance of careful consideration of data mechanisms and potential biases in interpretation.

The exploration of Prediction-Powered Inference, as detailed in the paper, embodies a systematic dismantling of conventional statistical assumptions. It isn’t merely about refining existing methods, but about fundamentally re-engineering the process of drawing conclusions from incomplete data. This approach, which prioritizes leveraging machine learning predictions to correct for bias, resonates with the spirit of intellectual rebellion. As Albert Camus noted, “The only way to deal with an unfree world is to become so absolutely free that your very existence is an act of rebellion.” PPI, in its pursuit of semiparametric efficiency and doubly robust estimation, performs a similar act – challenging the limitations of traditional inference and asserting a new freedom in the face of missing data.

Beyond the Horizon

The current iteration of Prediction-Powered Inference, while elegantly addressing the specter of missing data, feels…contained. It’s a powerful tool for correcting existing analyses, for patching holes in established methodologies. But true progress rarely lies in refinement. The real challenge isn’t simply making existing statistical frameworks more accurate; it’s dismantling the assumptions that necessitate such corrections in the first place. Doubly robustness is a safety net, not a fundamental redesign.

Future explorations should focus less on achieving efficiency within semiparametric models and more on scenarios where those models demonstrably fail. Stress-testing PPI against profoundly misspecified conditions – where the very notion of a “correct” model is suspect – will reveal its true limitations. Can this framework be adapted to actively learn the missing data mechanism, or is it inherently reliant on external assumptions? The answers likely reside in blurring the lines between estimation and causal inference – treating missingness not as a nuisance, but as a signal.

Ultimately, Prediction-Powered Inference isn’t about better statistics; it’s about a shifting perspective. It suggests that prediction, often viewed as a separate endeavor, is deeply intertwined with comprehension. The pursuit of accurate inference, therefore, may require embracing the inherently exploratory nature of machine learning – accepting that the most valuable insights often emerge from deliberately breaking things, and then meticulously reconstructing them.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.20819.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Building 3D Worlds from Words: Is Reinforcement Learning the Key?

- The Best Directors of 2025

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- 20 Best TV Shows Featuring All-White Casts You Should See

- Umamusume: Gold Ship build guide

- Mel Gibson, 69, and Rosalind Ross, 35, Call It Quits After Nearly a Decade: “It’s Sad To End This Chapter in our Lives”

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 39th Developer Notes: 2.5th Anniversary Update

- The Most Famous Foreign Actresses of All Time

- Most Famous Richards in the World

2026-01-30 04:01