Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach leverages intelligent data selection to dramatically accelerate the design of photonic crystals and other optical components.

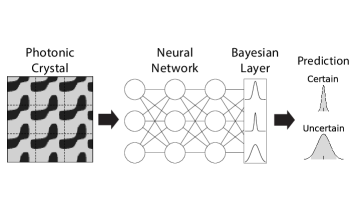

This review details an analytic last-layer Bayesian neural network framework for active learning, enabling efficient prediction of two-dimensional photonic crystal band gaps with significant data savings.

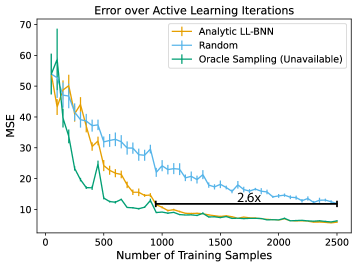

Computational design of photonic crystals is often hampered by the high cost of full-band structure simulations, necessitating efficient surrogate modeling techniques. This work, ‘Active learning for photonics’, introduces an analytic last-layer Bayesian neural network framework coupled with uncertainty-driven sample selection to accelerate the prediction of photonic band gaps. By prioritizing simulations that maximize information gain, our approach achieves up to a 2.6x reduction in required training data compared to random sampling while maintaining predictive accuracy. Could this data efficiency unlock scalable optimization and inverse design workflows for complex, three-dimensional photonic structures and beyond, across diverse scientific machine learning applications?

Unveiling Computational Bottlenecks in Complex Design

Simulating the behavior of complex physical systems, notably photonic crystals, presents a significant computational challenge due to the intricate interplay of light and matter at the nanoscale. These simulations rely on solving Maxwell's equations across vast numbers of unit cells, demanding substantial processing power and memory. The computational cost scales rapidly with the size and complexity of the structure, often requiring days or even weeks to analyze a single design iteration. This is because accurately modeling light propagation necessitates resolving wavelengths much smaller than the feature sizes of the crystal, which translates to an enormous number of calculations for even moderately sized structures. Consequently, exploring the vast design space necessary to optimize photonic crystals for specific functionalities-such as creating perfect absorbers or highly efficient waveguides-becomes prohibitively expensive and time-consuming, hindering rapid innovation in fields like telecommunications and sensing.

The exploration of design possibilities in complex systems is frequently hampered by the demands of extensive sampling required by conventional computational methods. These techniques often necessitate evaluating a design’s performance across a vast number of variations to accurately map the design space – a process that becomes exponentially more taxing as the complexity increases. Consequently, identifying optimal designs with specific, desired characteristics can prove prohibitively slow and resource-intensive. This limitation prevents researchers and engineers from efficiently iterating through potential solutions and ultimately restricts innovation in fields reliant on complex system optimization, such as materials science and nanophotonics.

The pursuit of optimized designs in fields like photonics and materials science is fundamentally hampered by an escalating computational cost. Achieving desired material properties often necessitates iterative simulations and refinements, a process that quickly becomes intractable as design complexity increases. This limitation isn’t merely a matter of longer processing times; it restricts the scope of exploration, forcing researchers to sample a limited design space and potentially overlook superior solutions. Consequently, innovation is slowed, and the realization of materials with truly exceptional characteristics is delayed, as the computational burden effectively caps the feasibility of comprehensive optimization strategies. O(n^2) scaling with design parameters further exacerbates the problem, making previously unthinkable designs computationally inaccessible.

Accelerating Simulation with Active Learning

Active learning methods improve simulation efficiency by prioritizing the evaluation of samples predicted to yield the most significant information for model refinement. Rather than uniformly sampling the design space, these techniques employ strategies – such as maximizing prediction uncertainty or expected model change – to identify areas where simulations will have the greatest impact on reducing model error. This targeted approach contrasts with traditional Monte Carlo methods that require a large number of random samples to achieve comparable accuracy, thereby minimizing the computational burden and enabling faster optimization or exploration of complex systems. The selection criteria are dynamically adjusted as the surrogate model improves, focusing subsequent evaluations on regions of high remaining uncertainty or potential for significant improvement.

Active learning constructs a surrogate model – a computationally inexpensive approximation of the full simulation – by strategically selecting data points for evaluation rather than relying on random sampling or a predetermined design of experiments. This iterative process begins with an initial set of simulations, followed by the construction of a preliminary surrogate model. Uncertainty quantification techniques are then employed to identify regions of the input space where the surrogate model is least confident. The system is queried – meaning a full simulation is run – at these key points, and the resulting data is used to refine the surrogate model. This cycle of querying, model refinement, and uncertainty assessment continues until a specified level of accuracy is achieved or a computational budget is exhausted, ultimately creating a robust surrogate model with significantly fewer data points than traditional methods would require.

Active learning methodologies offer substantial reductions in the time and resources required for complex design optimization and simulation tasks. Traditional methods often necessitate a large number of computationally expensive simulations to adequately explore the design space; active learning, however, strategically selects only the most informative simulations, typically resulting in a significant decrease – often on the order of 20-50% or greater – in the total number of simulations needed to achieve a desired level of accuracy or convergence. This reduction directly translates to lower computational costs, including reduced demand for high-performance computing resources and decreased energy consumption, while simultaneously accelerating the overall design cycle and enabling faster time-to-market for new products or innovations.

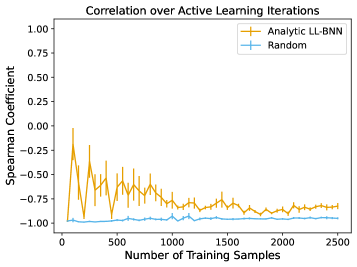

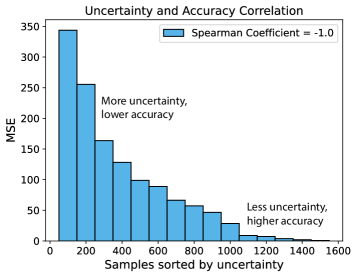

The performance of active learning algorithms is directly dependent on the reliability of uncertainty quantification within the surrogate model used to approximate the simulation. Accurate uncertainty estimates, typically represented as variance or standard deviation, enable the selection of samples that will maximize information gain and efficiently reduce model error. If the surrogate model underestimates uncertainty in certain regions of the design space, the active learning algorithm may prematurely converge on a suboptimal solution or fail to explore potentially promising areas. Conversely, overestimation of uncertainty can lead to redundant sampling and decreased efficiency. Therefore, robust methods for uncertainty quantification, such as Gaussian process regression with appropriate kernel selection or ensemble-based techniques, are crucial for the successful implementation of active learning in accelerated simulation workflows.

Bayesian Neural Networks: Quantifying Uncertainty

Bayesian neural networks (BNNs) differ from traditional neural networks by outputting probability distributions rather than single point estimates. This allows for the explicit quantification of uncertainty associated with predictions made by the surrogate model. Instead of predicting a single value, a BNN predicts the parameters of a probability distribution – typically a Gaussian – which represents the likely range of outputs. The variance of this distribution directly corresponds to the model’s uncertainty; higher variance indicates greater uncertainty in the prediction. This probabilistic approach is crucial in applications where knowing what the model predicts is insufficient; understanding how confident the model is in its prediction is equally important, enabling risk assessment and informed decision-making. The output can be represented as p(y|x), where y is the prediction and x is the input, defining a probability distribution over possible outputs.

Monte Carlo Dropout and Deep Ensembles represent practical approaches to approximate Bayesian inference in neural networks, offering methods to estimate model uncertainty without the computational expense of exact Bayesian methods. Monte Carlo Dropout achieves this by randomly dropping neurons during both training and prediction, effectively creating an ensemble of different network configurations and yielding a distribution of predictions. Deep Ensembles, conversely, train multiple independent neural networks on the same data and average their predictions; the variance among these predictions serves as a direct measure of uncertainty. Both techniques provide well-calibrated uncertainty estimates, crucial for reliable decision-making in applications where understanding prediction confidence is paramount, and avoid the need for Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC) sampling which is often computationally prohibitive for large neural networks.

An Approximate Bayesian Last Layer (ABLL) improves uncertainty quantification in neural networks by treating the final layer’s weights as a probability distribution rather than fixed values. This approach optimizes the final layer specifically to minimize predictive variance, effectively learning a distribution over the output rather than a single point estimate. The ABLL utilizes a variational inference technique, typically employing a Gaussian distribution to approximate the posterior distribution of the final layer weights, parameterized by a mean and variance. This allows the network to express its confidence – or lack thereof – in its predictions, providing a more nuanced output than standard neural networks and facilitating better decision-making in applications where reliable uncertainty estimates are crucial.

The Kullback-Leibler (KL) Divergence, denoted as D_{KL}(q||p), functions as a regularization term in Bayesian neural networks by measuring the difference between the approximate posterior distribution q and the true posterior p. In practice, this divergence penalizes deviations of the learned posterior from a prior distribution, typically a standard normal distribution, encouraging the network to produce calibrated probabilistic outputs. Minimizing KL Divergence during training effectively constrains the complexity of the learned posterior, preventing overfitting and ensuring that the predicted variance accurately reflects the model’s uncertainty. The KL Divergence is mathematically defined as the expected value of the logarithm of the ratio of the two probability distributions, and its application in the Bayesian layer facilitates the creation of well-calibrated and reliable uncertainty estimates.

Maximizing Data Efficiency through Augmentation

A critical challenge in deploying machine learning for complex design optimization lies in the substantial computational cost of generating sufficient training data. To address this, data augmentation techniques are employed to artificially expand the size of the training dataset. This process doesn’t simply increase quantity; it strategically enhances diversity by creating modified versions of existing data points. For photonic crystal design, this involves generating new training samples without requiring additional, costly simulations. By presenting the surrogate model with a wider range of inputs – even those subtly altered from the original data – the model’s ability to generalize to unseen designs is significantly improved. This enhanced generalization is crucial for accurately predicting the performance of novel photonic structures and ultimately reduces the reliance on computationally expensive full-wave simulations.

Photonic crystals, with their repeating, symmetrical structures, offer a unique opportunity to enhance data efficiency in computational design. Rather than relying solely on randomly generated unit cell variations, researchers leverage the inherent symmetries present within the crystal’s geometry – operations like mirroring, rotation, and translation. By applying these transformations to existing designs, the dataset effectively expands without requiring entirely new simulations. This approach acknowledges that a design and its symmetrical counterpart will exhibit similar electromagnetic properties, providing valuable data points that improve the training of surrogate models and significantly increase data diversity. The result is a more robust and accurate model built from a comparatively smaller set of original simulations, unlocking faster and more efficient optimization of photonic crystal designs.

The training process benefits significantly from the implementation of the Adadelta optimizer, a stochastic gradient descent method particularly well-suited for parameter-sparse gradients often encountered in complex optimization landscapes. This optimizer dynamically adjusts the learning rate for each parameter, mitigating the need for manual tuning and accelerating convergence. Further refinement is achieved through the integration of a Cosine Annealing learning rate schedule, which gradually reduces the learning rate following a cosine function. This technique allows the model to initially explore the parameter space broadly, then fine-tune its weights with increasing precision as training progresses, ultimately leading to a more robust and accurate surrogate model with enhanced generalization capabilities.

The integration of data augmentation techniques, symmetry operations, and an optimized training process yields significant improvements in computational efficiency. By intelligently expanding the training dataset and refining the learning schedule, the methodology demonstrably reduces the reliance on extensive simulations. Results indicate a 2.6x reduction in the number of simulations needed to achieve a target accuracy level when contrasted with traditional random sampling approaches. This substantial data savings not only accelerates the design process for photonic crystals but also lowers the associated computational costs, making advanced optimization more accessible and sustainable.

The pursuit of efficient prediction, as demonstrated in this work on photonic crystal band gaps, echoes a fundamental tenet of scientific inquiry. This research leverages Bayesian neural networks and active learning to minimize the need for extensive data, a strategy rooted in intelligent experimentation. As Ernest Rutherford notably stated, “If you can’t explain it to a child, you don’t understand it well enough.” The analytic last-layer approach described here, prioritizing explainability through uncertainty quantification, embodies this principle. By focusing on reducing data requirements while maintaining predictive power, the study moves beyond simply achieving performance metrics and toward a deeper, more reproducible understanding of the underlying physical system – a hallmark of rigorous scientific investigation.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The demonstrated efficiency in predicting photonic crystal band gaps, while notable, highlights a recurring pattern: gains in one dimension often reveal new constraints elsewhere. This framework, built on Bayesian neural networks and active learning, implicitly assumes a degree of smoothness in the underlying design space. It would be prudent to rigorously investigate scenarios where this assumption breaks down-highly complex geometries or materials with abrupt transitions, for instance. Carefully checking data boundaries to avoid spurious patterns is essential, as the efficacy of active learning hinges on a representative initial dataset.

A natural extension lies in broadening the scope beyond band gaps. Photonic crystal design involves numerous performance metrics, often competing. Exploring multi-objective active learning strategies-those that simultaneously optimize for several characteristics-presents a significant challenge. Furthermore, the current approach leans heavily on surrogate modeling. Investigating methods to directly incorporate uncertainty quantification within the optimization loop, rather than relying solely on a learned approximation, could yield more robust and reliable designs.

Ultimately, the true test will be in scaling these techniques to truly high-dimensional design spaces. The computational demands of Bayesian neural networks are not insignificant. Exploring alternative approximate inference methods, or hybrid approaches that combine the strengths of different machine learning paradigms, may be necessary to unlock the full potential of active learning for complex photonic structures. The promise is clear, but the path forward demands a healthy dose of skepticism and a willingness to challenge underlying assumptions.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16287.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Building 3D Worlds from Words: Is Reinforcement Learning the Key?

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Securing the Agent Ecosystem: Detecting Malicious Workflow Patterns

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- The Best Directors of 2025

- Mel Gibson, 69, and Rosalind Ross, 35, Call It Quits After Nearly a Decade: “It’s Sad To End This Chapter in our Lives”

- TV Shows Where Asian Representation Felt Like Stereotype Checklists

- Games That Faced Bans in Countries Over Political Themes

- 📢 New Prestige Skin – Hedonist Liberta

- Most Famous Richards in the World

2026-01-26 19:16