Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study reveals that established convolutional neural networks can effectively detect tree canopies with remarkably limited training data, outperforming more recent vision transformer architectures in low-data remote sensing.

Fine-tuning conventional models like YOLOv11 and Mask R-CNN proves more effective than vision transformers for tree canopy instance segmentation when training datasets are constrained to just 150 images.

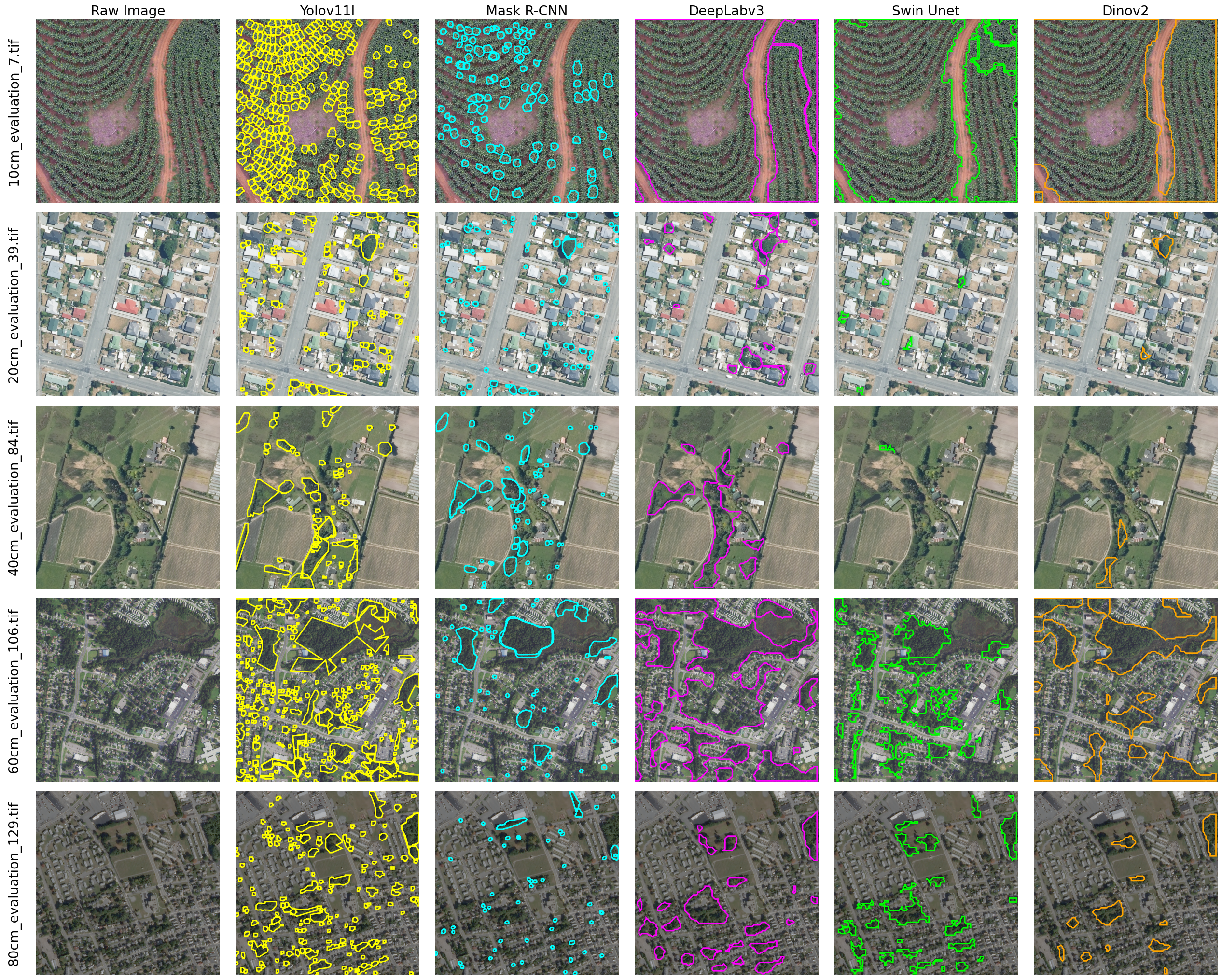

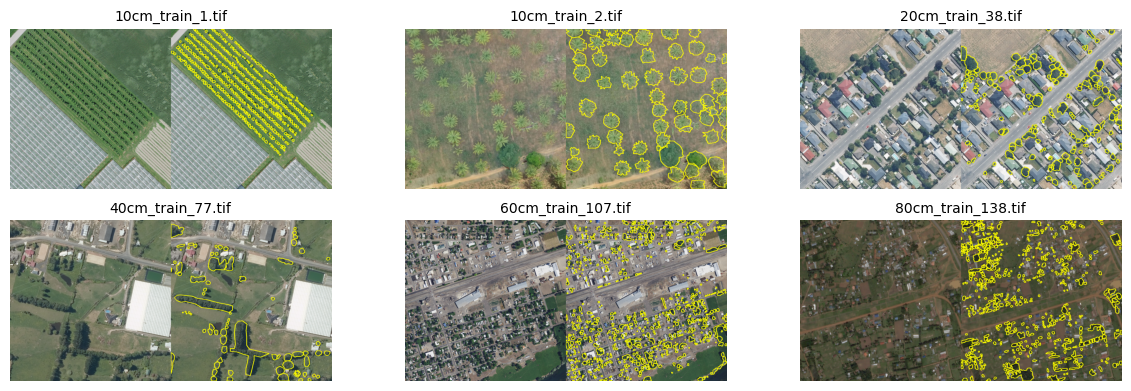

Despite advances in deep learning, reliably segmenting tree canopies from aerial imagery remains challenging when training data is severely limited. This is addressed in ‘Sparse Data Tree Canopy Segmentation: Fine-Tuning Leading Pretrained Models on Only 150 Images’, which comparatively evaluates the performance of five leading architectures-YOLOv11, Mask R-CNN, DeepLabv3, Swin-UNet, and DINOv2-under extreme data scarcity. Experiments reveal that lightweight convolutional neural networks, particularly YOLOv11 and Mask R-CNN, significantly outperform vision transformers in this low-data regime, highlighting the importance of spatial inductive biases for remote sensing tasks. Given these findings, what strategies can best bridge the performance gap between CNNs and ViTs when applying deep learning to similarly constrained environmental monitoring applications?

Unveiling Patterns in Limited Data: The Challenge of Tree Canopy Detection

Effective forest management increasingly relies on accurate identification of tree canopies from remotely sensed data, providing crucial insights into forest health, biodiversity, and carbon storage. However, a significant obstacle remains: the scarcity of meticulously labeled training data. Creating these datasets-where each tree canopy is individually identified and mapped-is a time-consuming and expensive process, limiting the scale and accuracy of automated detection algorithms. This data bottleneck particularly impacts the application of advanced machine learning techniques, which typically require vast amounts of labeled examples to generalize effectively across diverse landscapes and varying imaging conditions. Consequently, researchers are actively exploring methods to maximize performance with limited labeled data, including techniques like transfer learning and data augmentation, to bridge the gap between algorithmic potential and real-world applicability in forestry and environmental monitoring.

Conventional approaches to tree canopy detection often falter when confronted with the inherent intricacies of natural landscapes. These methods, typically reliant on extensive datasets to discern patterns and features, struggle to differentiate tree canopies from background clutter – shadows, undergrowth, or varying terrain – without a wealth of labeled examples. The challenge stems from the high dimensionality and variability within remote sensing imagery; subtle shifts in illumination, viewing angle, or species composition can significantly alter the spectral signature of a canopy, demanding increasingly complex models. However, pursuing excessive model complexity without sufficient data leads to overfitting, where the algorithm memorizes the training set but fails to generalize to new, unseen environments, ultimately hindering accurate and reliable canopy delineation.

Successfully identifying tree canopies within complex remote sensing imagery presents a significant hurdle: balancing the desire for sophisticated models with the reality of limited labeled data. Highly complex models, while potentially more accurate with abundant data, are prone to overfitting when trained on sparse datasets – essentially memorizing the training examples rather than learning generalizable features of tree canopies. This leads to poor performance on unseen imagery. Conversely, overly simplistic models may lack the capacity to capture the subtle nuances of natural scenes, resulting in inaccurate detections. Therefore, researchers must carefully navigate this trade-off, employing techniques like data augmentation, transfer learning, and regularization to create models that are both powerful enough to discern tree canopies and robust enough to generalize to new, unobserved environments – ensuring reliable forest monitoring and management even with constrained data resources.

Leveraging Prior Knowledge: Pretraining and Inductive Bias for Robust Segmentation

Pretraining involves initializing a model with weights learned from a large, generally unlabeled, dataset before fine-tuning on a smaller, task-specific labeled dataset. This transfer of learned representations significantly reduces the number of labeled examples required to achieve comparable performance to models trained from scratch. The underlying principle is that the pretrained model has already learned general features and patterns present in the data, allowing it to converge more quickly and effectively on the target task with fewer task-specific labeled samples. This is particularly beneficial in segmentation tasks where acquiring pixel-level annotations is often expensive and time-consuming; pretraining can mitigate the need for massive, fully-annotated datasets.

Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs) exhibit inherent spatial inductive biases due to their architectural design. Specifically, the use of convolutional filters encourages the network to learn features that are spatially local and translationally equivariant – meaning a feature detected in one part of an image is also recognized if it appears elsewhere. This is achieved through weight sharing, reducing the number of parameters and promoting generalization. Consequently, CNNs can effectively segment images even when trained with a limited number of labeled examples, as the built-in assumptions about image structure reduce the reliance on extensive data to learn basic visual patterns and relationships between pixels. This is particularly beneficial in segmentation tasks where understanding spatial context is critical for accurately delineating object boundaries.

Despite the benefits of pretraining and inherent inductive biases in convolutional architectures, performance degradation can occur when segmenting complex scenes or datasets lacking sufficient diversity. Specifically, models pretrained on general image datasets may not generalize well to images with unusual compositions, novel object interactions, or domain-specific features not represented in the pretraining corpus. Similarly, limited data diversity during fine-tuning can lead to overfitting on the available examples, reducing the model’s ability to accurately segment unseen instances or handle variations in lighting, occlusion, and viewpoint. This is especially pronounced in scenarios demanding precise boundary delineation or accurate identification of rare or atypical objects.

Vision Transformers: Exploring Potential and Addressing Limitations in Remote Sensing

Vision Transformers, including architectures like Swin-UNet and DINOv2, demonstrate significant capability in extracting meaningful features for semantic segmentation tasks. These models utilize self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies within image data, enabling them to learn robust representations that outperform traditional convolutional neural networks in certain scenarios. This is achieved by processing images as sequences of patches, allowing the transformer to model relationships between all parts of the input, unlike convolutional networks which are limited by receptive field size. The learned representations are then used for pixel-wise classification, effectively segmenting images into distinct classes or regions.

Evaluation of Vision Transformer architectures – specifically Swin-UNet, DINOv2, and DeepLabV3 – on the validation dataset yielded weighted mean Average Precision (mAP) scores of 0.85, 0.82, and 0.82 respectively. These results indicate a performance limitation when applied to this specific dataset. The comparatively lower scores suggest these models exhibit a significant dependency on the quantity and characteristics of the training data, and may not generalize effectively when evaluated on datasets with differing distributions or limited examples. This data dependency necessitates careful consideration of dataset size and representativeness when deploying these architectures for remote sensing tasks.

The performance of Vision Transformers in remote sensing applications is critically dependent on both the quality of pretraining and the implementation of effective regularization techniques. Insufficient pretraining can result in models that lack the robust feature extraction capabilities needed for generalization to new datasets. Furthermore, the inherent complexity of Vision Transformers, particularly with limited training data, makes them susceptible to overfitting; regularization methods such as weight decay, dropout, and data augmentation are therefore essential to constrain model complexity and improve performance on unseen data. Successful deployment requires careful consideration of these factors to maximize generalization ability and prevent poor performance in real-world scenarios.

Dissecting Performance: A Comparative Analysis of Precision and Recall

Mask R-CNN exhibits remarkable efficacy in instance segmentation, even when trained with constrained datasets. Evaluations on the Solafune test set reveal a weighted mean Average Precision (mAP) of 0.22, demonstrating its capacity to accurately identify and delineate individual objects within complex scenes despite limited training examples. This performance underscores the advantages of the model’s robust architecture, which effectively combines object detection with pixel-level segmentation, allowing it to generalize well from sparse data and maintain a high degree of accuracy in identifying and isolating instances of objects.

Despite achieving a pixel accuracy of 0.82, indicating overall correct classification of pixels, the DeepLabv3 model demonstrated limitations in accurately defining object boundaries during semantic segmentation. This is reflected in its comparatively low weighted mean Average Precision (mAP) score of 0.038 on the Solafune test set. While capable of broadly identifying areas belonging to different classes, the model frequently struggled with precise object delineation, leading to blurred or imprecise segmentation masks. This suggests that, although it can correctly label pixels, DeepLabv3 lacks the granularity needed for tasks requiring detailed object localization and shape recognition, highlighting a trade-off between overall accuracy and the precision of object boundaries.

YOLOv11 distinguishes itself through a combination of architectural design and a strategy of extensive pretraining, resulting in leading performance on the Solafune test set. Achieving a weighted mean Average Precision (mAP) of 0.281, the model demonstrates a superior ability to accurately identify and localize objects within images. This level of performance isn’t simply about accuracy; YOLOv11 also prioritizes efficient detection, processing images quickly while maintaining precision. The extensive pretraining phase allows the model to learn robust feature representations from a large dataset, effectively transferring knowledge to the specific instance segmentation task and establishing a compelling benchmark for future model development in this area.

Charting a Course Forward: Future Directions in Tree Canopy Detection

Addressing the challenge of limited labeled data for tree canopy detection necessitates innovative strategies for model generalization. Current research is increasingly focused on data augmentation techniques, artificially expanding training datasets through transformations like rotations, scaling, and color adjustments. These methods help models become more invariant to variations in tree appearance and viewing angles. Complementing this, transfer learning leverages knowledge gained from training on large, related datasets – such as general object recognition – to initialize model weights. This pre-training significantly reduces the amount of labeled tree canopy data required for effective training, allowing models to achieve robust performance even with scarce resources. The combined application of these techniques promises to substantially improve the accuracy and reliability of tree canopy detection systems in data-constrained environments.

Advancements in tree canopy detection could benefit significantly from architectural refinements inspired by semantic image segmentation techniques. Specifically, integrating dilated convolutions and atrous spatial pyramid pooling (ASPP), as demonstrated in the DeepLabv3 model, offers a pathway to improved performance. Dilated convolutions allow for a larger receptive field without increasing the number of parameters, enabling the network to capture broader contextual information crucial for delineating complex canopy shapes. ASPP further refines this by employing multiple dilated convolutions with varying dilation rates, effectively capturing objects at different scales. By incorporating these mechanisms into robust detection architectures, researchers aim to enhance the ability to accurately identify and map tree canopies, even in challenging environments with varying densities and overlapping vegetation.

A thorough evaluation of tree canopy detection models necessitates the combined use of pixel accuracy and mean average precision (mAP). Pixel accuracy, while providing a general overview of correct classification, can be misleading in scenarios with imbalanced datasets or small canopy sizes – a common occurrence in complex forest environments. mAP, however, offers a more nuanced assessment by considering both precision and recall across different Intersection over Union (IoU) thresholds, effectively measuring the accuracy of canopy localization as well as classification. Therefore, relying solely on pixel accuracy risks overlooking critical localization errors, while a combined approach utilizing both metrics provides a comprehensive understanding of model performance and facilitates robust comparisons between different detection strategies, ultimately driving advancements in automated forest monitoring and ecological research.

The study’s findings resonate with David Marr’s assertion that, “Vision is not about receiving images, but about constructing representations.” This research actively constructs representations of tree canopies, but notably emphasizes how that construction occurs – leveraging the spatial inductive biases inherent in CNN architectures. The paper demonstrates that, in scenarios mirroring real-world remote sensing constraints – limited data – these biases allow for more robust feature extraction and, ultimately, superior performance compared to vision transformers. This echoes Marr’s focus on understanding the computational processes underlying perception, showing that prior knowledge-in this case, spatial relationships-plays a crucial role when data is scarce.

Looking Ahead

The demonstrated resilience of convolutional neural networks in low-data regimes for tree canopy detection suggests a curious truth: sometimes, the most sophisticated architectures aren’t the answer. The field chases ever-larger models and datasets, yet this work subtly implies a limit to the benefit of scale when data is genuinely scarce. The relative failure of vision transformers – models so promising in other domains – begs the question of whether the inductive biases inherent in CNNs remain critically important for interpreting the spatially coherent, but often noisy, patterns present in remote sensing imagery.

A crucial, unaddressed element remains the characteristics of the 150 images used for training. Were these images representative of the broader range of canopy structures, illumination conditions, and sensor modalities? The performance differences between models could be amplified, or even reversed, with a different sampling of the possible data space. Further investigation into the transferability of these fine-tuned models across diverse geographic locations and sensor types is paramount.

Ultimately, the limitations aren’t merely technical. The drive for ‘more data’ often overshadows the need for better data – meticulously labeled, representative samples that capture the true complexity of the system. The future likely lies not in simply scaling up, but in intelligently curating data and designing architectures that acknowledge the fundamental constraints of the problem. The signal is there; it’s discerning it from the noise that proves the true challenge.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10931.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Securing the Agent Ecosystem: Detecting Malicious Workflow Patterns

- DOT PREDICTION. DOT cryptocurrency

- Silver Rate Forecast

- 4 Reasons to Buy Interactive Brokers Stock Like There’s No Tomorrow

- EUR UAH PREDICTION

- NEAR PREDICTION. NEAR cryptocurrency

- Top 15 Insanely Popular Android Games

- Did Alan Cumming Reveal Comic-Accurate Costume for AVENGERS: DOOMSDAY?

- USD COP PREDICTION

2026-01-21 02:57