Author: Denis Avetisyan

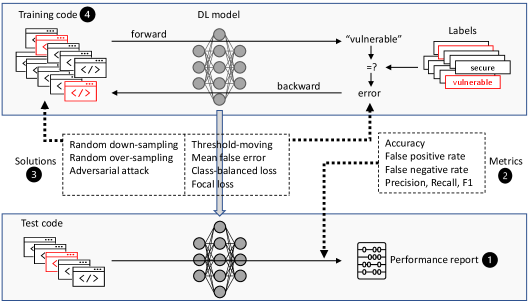

A new study reveals that common data imbalance issues significantly hinder the performance of deep learning models used to identify software vulnerabilities.

Existing data augmentation and model-level solutions offer limited gains for software vulnerability detection, necessitating tailored approaches that account for the unique characteristics of vulnerability data.

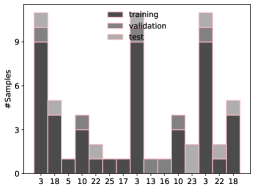

Despite advances in deep learning for automated software security, vulnerability detection models continue to exhibit inconsistent performance across datasets. This paper, ‘An Empirical Study of the Imbalance Issue in Software Vulnerability Detection’, systematically investigates the hypothesis that this variability stems from a significant class imbalance-the relative scarcity of vulnerable code. Through a comprehensive empirical evaluation using nine open-source datasets and two state-of-the-art models, we confirm this conjecture and demonstrate that while existing imbalance mitigation techniques offer some improvement, their effectiveness varies considerably depending on the dataset and evaluation metric. This raises the question of how to develop tailored solutions that effectively address the unique challenges of data imbalance in the context of software vulnerability detection.

The Challenge of Imbalanced Data in Vulnerability Detection

Modern software vulnerability detection increasingly leverages the power of machine learning, and specifically, Deep Learning techniques. These methods, inspired by the structure and function of the human brain, excel at identifying complex patterns within code that might indicate security flaws. Deep Learning models, such as Convolutional Neural Networks and Recurrent Neural Networks, are trained on vast amounts of source code to learn the characteristics of both secure and vulnerable implementations. This approach allows automated systems to scan codebases far more efficiently than manual review, potentially identifying vulnerabilities before they can be exploited. The promise of these techniques lies in their ability to generalize from learned patterns, enabling the detection of novel vulnerabilities beyond those explicitly present in the training data, though challenges related to data imbalance – a disproportionate representation of secure versus vulnerable code – frequently impact their effectiveness.

The pervasive issue of imbalanced datasets presents a substantial challenge to effective vulnerability detection. Machine learning models, frequently employed to identify software flaws, are often trained on data where examples of secure code vastly outnumber those containing vulnerabilities. This disproportionate representation can lead to models that exhibit high overall accuracy – correctly identifying secure code most of the time – but fail to effectively pinpoint the critical, and far rarer, instances of vulnerable code. Consequently, a model might appear successful based on general performance metrics, while simultaneously exhibiting poor performance on the very task it is designed to accomplish: accurately detecting security flaws. This skew in training data fundamentally biases the model, diminishing its ability to generalize and reliably identify vulnerabilities in real-world applications.

Conventional metrics like accuracy can be deceptively high in vulnerability detection, despite a model’s failure to effectively pinpoint actual security flaws. Studies utilizing the Asterisk dataset, as detailed by Lin2018, demonstrate this issue starkly; while a model might achieve 99.77% accuracy in identifying secure code, its performance on the crucial task of detecting vulnerable code can plummet to as low as 44.44%. This disparity arises because the overwhelming majority of code samples are secure, leading the model to prioritize correctly classifying non-vulnerable instances, even at the expense of missing genuine vulnerabilities – a critical failing in any security application. Consequently, relying solely on overall accuracy provides a misleadingly optimistic assessment, and necessitates the use of more nuanced evaluation metrics focused specifically on the detection of vulnerabilities.

![A vulnerable function within the LibTIFF project exhibits a potential denial-of-service flaw due to an unchecked division by zero (<span class="katex-eq" data-katex-display="false">m.i[1] == 0</span>), as identified in the Lin2018 dataset.](https://arxiv.org/html/2602.12038v1/x1.png)

Strategies for Addressing Data Imbalance

Data-level techniques address class imbalance by modifying the dataset’s composition. Random over-sampling increases the representation of the minority class by replicating existing samples; this is a straightforward method but can lead to overfitting. Conversely, random down-sampling reduces the number of samples in the majority class through random deletion, potentially discarding useful information. Both methods are implemented prior to model training and aim to provide a more balanced distribution of classes, improving the model’s ability to learn from under-represented examples without altering the samples themselves beyond duplication or removal.

Adversarial Attack-Based Augmentation addresses data imbalance by creating synthetic vulnerable code samples. This technique leverages algorithms that intentionally perturb existing code, generating variations that are still considered vulnerable but differ from the original examples. These newly generated samples are added to the minority class, increasing its representation in the training dataset. The perturbations are designed to be subtle enough to maintain the vulnerability while introducing sufficient diversity to improve model generalization and prevent overfitting to the limited original data. Unlike random over-sampling, this method does not simply duplicate existing samples, but instead aims to create new, realistic instances of vulnerable code.

Model-level strategies address data imbalance by modifying the loss function to prioritize learning from the minority class. Techniques like Focal Loss dynamically adjust the weighting based on the confidence of the prediction, reducing the loss contribution from easily classified samples and focusing on hard-to-classify, often misclassified, vulnerable samples. Class-Balanced Loss, conversely, assigns a fixed weight to each class inversely proportional to its frequency. Experimental results indicated that, while these methods improve performance on imbalanced datasets, random over-sampling generally achieved the highest F1 scores, suggesting a simpler approach can be highly effective in this context.

Beyond Accuracy: Robust Evaluation of Vulnerability Detection

Precision and Recall are key metrics for evaluating vulnerability detection models. Precision, calculated as \frac{True\ Positives}{True\ Positives + False\ Positives} , quantifies the accuracy of positive predictions – specifically, the proportion of flagged vulnerabilities that are genuine. Conversely, Recall, calculated as \frac{True\ Positives}{True\ Positives + False\ Negatives} , measures the model’s ability to find all actual vulnerabilities, representing the proportion of existing vulnerabilities correctly identified. A high precision indicates fewer false positives, while high recall indicates fewer false negatives; both are critical but represent different aspects of a model’s performance, and are often considered in conjunction, such as with the F1-Measure.

The F1-Measure represents the harmonic mean of Precision and Recall, calculated as 2 <i> (Precision </i> Recall) / (Precision + Recall). This metric provides a single score that balances the trade-off between identifying vulnerabilities correctly (Precision) and finding all actual vulnerabilities (Recall). Unlike relying solely on accuracy, which can be misleading with imbalanced datasets, the F1-Measure offers a more comprehensive evaluation, particularly when both false positives and false negatives are costly. A high F1-Measure indicates that the model achieves both high precision and high recall, demonstrating robust performance in vulnerability detection.

Analysis of vulnerability detection models revealed a high false negative rate of 68.05% when class imbalance was not addressed, indicating the model frequently failed to identify actual vulnerabilities. This imbalance necessitates mitigation strategies such as oversampling minority classes, undersampling majority classes, or employing cost-sensitive learning. Furthermore, detailed analysis of the vulnerability type distribution within the dataset is crucial; significant disparities in the representation of different vulnerability types can introduce bias and negatively impact the model’s ability to generalize effectively across all vulnerability categories. Accurate identification of this distribution informs both mitigation strategy selection and a comprehensive understanding of model limitations.

Foundation Models: A Paradigm Shift in Vulnerability Detection

Foundation models such as CodeBERT and GraphCodeBERT represent a significant advancement in automated code analysis due to their pre-training on extensive code repositories. This pre-training process allows these models to develop a deep understanding of not just the syntax, but also the semantics of programming languages – essentially, what the code means rather than just how it’s written. By absorbing patterns and relationships from millions of lines of code, the models learn to recognize common programming structures, identify potential errors, and even predict how different code segments will interact. This ability to discern complex relationships within code is crucial for tasks like vulnerability detection, bug fixing, and code completion, offering a substantial improvement over traditional, rule-based approaches that often struggle with the nuances of real-world codebases.

GraphCodeBERT distinguishes itself through its innovative use of a code’s data flow graph to pinpoint potential vulnerabilities. Rather than simply analyzing the code’s syntax, this model maps how information moves through the program – tracing the journey of variables and the operations performed on them. By representing code as a graph where nodes represent operations and edges depict data dependencies, GraphCodeBERT can effectively identify vulnerabilities arising from improper data handling, such as tainted inputs reaching sensitive functions. This approach allows the model to detect issues that traditional methods might miss, offering a more nuanced and accurate assessment of code security by focusing on the behavior of data within the application, rather than solely on its static structure.

The practical application of foundation models like CodeBERT and GraphCodeBERT in vulnerability detection is often challenged by a phenomenon known as Data Distribution Shift. This occurs when the characteristics of the code encountered during testing differ significantly from the code used during the model’s initial training. Such discrepancies – perhaps involving different programming languages, coding styles, or application domains – can degrade the model’s performance, leading to decreased accuracy and increased false positives. Consequently, continuous adaptation and refinement are crucial; models must be regularly retrained or fine-tuned with new data representative of the evolving codebase to maintain their effectiveness and ensure reliable vulnerability detection over time. This ongoing process helps the model generalize better and remain robust against shifts in data characteristics, ultimately maximizing its utility in real-world security applications.

The pursuit of effective software vulnerability detection, as detailed in the study, often introduces complexity through various mitigation strategies. However, the core issue – data imbalance – frequently remains inadequately addressed. This resonates with John von Neumann’s observation: “It is possible to carry out an indefinite number of operations without obtaining a result.” The study reveals that simply applying solutions borrowed from other domains, even with sophisticated deep learning techniques, doesn’t guarantee improvement. true progress necessitates a focused approach, stripping away extraneous layers to reveal the underlying vulnerability-specific factors that impact model performance. The work advocates for a minimalist philosophy-removing ineffective techniques to expose what truly matters in achieving reliable detection.

The Road Ahead

The persistence of imbalance, even when importing solutions from established machine learning domains, suggests a fundamental mismatch. It is not simply a matter of more data, or even smarter augmentation. The core issue resides within the very nature of software vulnerabilities – their rarity, their specificity, and the subtle semantic distinctions that separate benign code from exploitable flaws. A purely quantitative approach, however ingenious, will continue to yield diminishing returns.

Future work must move beyond treating vulnerabilities as generic anomalies. The field requires a deeper engagement with program analysis techniques, not to find vulnerabilities directly, but to inform the construction of more effective training data. Synthetic data generation, guided by symbolic execution or fuzzing, holds greater promise than blind augmentation. Furthermore, evaluation metrics must evolve beyond simple precision and recall, acknowledging the disproportionate cost of false negatives in security contexts.

Foundation models, while intriguing, are not a panacea. Their inherent biases, trained on vast corpora of general-purpose code, may obscure the critical details that distinguish vulnerable code. The true challenge lies not in scaling existing models, but in distilling knowledge from limited, high-quality vulnerability datasets – a process that demands careful consideration of feature engineering, representation learning, and, ultimately, a more nuanced understanding of what constitutes a ‘vulnerable’ program.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.12038.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Securing the Agent Ecosystem: Detecting Malicious Workflow Patterns

- NEAR PREDICTION. NEAR cryptocurrency

- Wuthering Waves – Galbrena build and materials guide

- DOT PREDICTION. DOT cryptocurrency

- USD COP PREDICTION

- Silver Rate Forecast

- EUR UAH PREDICTION

- USD KRW PREDICTION

- Games That Faced Bans in Countries Over Political Themes

2026-02-15 02:16