Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that convolutional neural networks used for image restoration are remarkably similar to mathematically optimal estimators, providing a foundation for understanding their performance.

This work demonstrates that trained CNNs approximate constrained Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE) estimators, offering an analytic framework for understanding generalization and the role of functional constraints in inverse problems.

Despite the widespread empirical success of convolutional neural networks (CNNs) in solving imaging inverse problems, a comprehensive theoretical understanding of their behavior has remained elusive. This work, ‘An analytic theory of convolutional neural network inverse problems solvers’, bridges this gap by demonstrating that trained CNNs closely approximate analytically derived constrained Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE) estimators, incorporating key inductive biases of translation equivariance and locality. This constrained variant, termed Local-Equivariant MMSE (LE-MMSE), provides a tractable framework for interpreting and predicting CNN performance across diverse tasks and architectures. Can this theoretical lens illuminate the generalization capabilities of CNNs and guide the development of more robust and efficient image restoration techniques?

Whispers of Chaos: The Inverse Problem

A vast range of signal processing challenges are fundamentally ‘inverse problems’ – tasks where the goal isn’t to predict a signal’s evolution forward in time, but rather to reconstruct a signal given incomplete or noisy observations. This is particularly evident in image restoration, where a degraded image – blurred, noisy, or incomplete – serves as the observation, and the original, pristine image is the desired reconstruction. However, the scope extends far beyond visual data; inverse problems arise in medical imaging like MRI and CT scans, geophysical exploration where signals are used to image subsurface structures, and even astronomical observations attempting to resolve distant galaxies from faint light. Effectively solving these problems requires sophisticated techniques capable of inferring the underlying signal from indirect and often ambiguous data, making the study of inverse problems central to advancements in numerous scientific and engineering fields.

Traditional estimation techniques, such as the Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE) estimator, encounter significant challenges when applied to complex, high-dimensional data sets. The core difficulty stems from the ‘curse of dimensionality’, where the number of unknown variables grows exponentially with the data’s size, rapidly depleting the available data to reliably estimate each parameter. This often results in poorly conditioned problems, meaning small changes in the input data can lead to large, unstable fluctuations in the estimated signal. Furthermore, the computational cost of these estimators scales poorly with dimensionality, making them impractical for many real-world applications involving extensive data like high-resolution images or large-scale sensor networks. Consequently, these methods frequently fail to accurately reconstruct the underlying signal, necessitating the development of more sophisticated approaches capable of handling the intricacies of modern data analysis.

Traditional signal estimation techniques often falter when confronted with real-world data due to a fundamental limitation: their inability to effectively leverage prior knowledge about the signal itself. Many standard methods, while mathematically elegant, operate largely independent of any understanding of the signal’s inherent structure – whether it’s known to be sparse, smooth, or exhibit specific patterns. This oversight results in suboptimal performance, as the estimator is forced to treat all possible signals as equally likely, even those that are physically implausible or inconsistent with established understanding. Consequently, estimates can be noisy, inaccurate, and fail to capture the true underlying information, particularly in high-dimensional scenarios where the data space is vast and the signal is weak. Incorporating such prior knowledge, through techniques like Bayesian estimation or regularization, can dramatically improve accuracy and robustness by guiding the estimation process towards more plausible solutions.

Constrained Estimation: Injecting the Ghost in the Machine

The Constrained Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE) estimator builds upon the standard MMSE framework by incorporating prior knowledge derived from Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs). Traditional MMSE estimation seeks to minimize the expected squared error between the estimate and the true value, relying on second-order statistics – the mean and covariance – of the signal and noise. The Constrained MMSE extends this by explicitly integrating the a priori assumptions embodied in CNN architectures – specifically, the network’s learned weights and biases – into the estimation process. This is achieved by modifying the standard MMSE equations to favor solutions consistent with these CNN-derived priors, effectively biasing the estimator towards more plausible or likely outcomes as defined by the CNN’s learned representation. The result is an estimator that combines data-driven statistical inference with the inductive biases inherent in CNNs, potentially improving accuracy and robustness, particularly in scenarios with limited data or high noise levels.

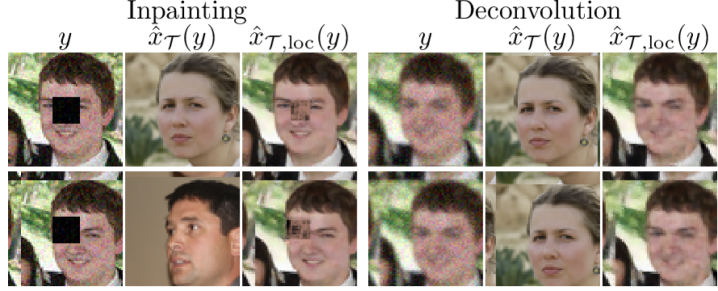

Functional constraints, utilized within the Constrained MMSE estimator, directly incorporate the inherent properties of Convolutional Neural Networks into the estimation process. Specifically, locality enforces that the estimated solution should vary smoothly with respect to local input changes, mirroring the spatially-constrained receptive fields of CNNs. Equivariance, conversely, demands that the estimated solution transforms consistently with known input transformations-such as translations or rotations-reflecting a CNN’s ability to recognize patterns regardless of their absolute location or orientation. These constraints are mathematically imposed as regularization terms, guiding the estimator towards solutions that adhere to these fundamental CNN characteristics and improving generalization performance by reducing the solution space.

The imposition of functional constraints – locality and equivariance – on the estimation process acts as a regularizer, reducing solution variance and preventing overfitting to noisy or incomplete data. By explicitly encoding the prior knowledge that nearby pixels are correlated and that object features maintain consistent relationships under transformations, the Constrained MMSE estimator biases the solution towards plausible outputs consistent with CNN architectures. This regularization effect enhances generalization performance, particularly in scenarios with limited training data or high levels of noise, as the constrained estimator is less susceptible to spurious correlations and better equipped to interpolate to unseen data points.

Analytical Tractability: Peeking Behind the Curtain

The constrained Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE) estimator was derived analytically by incorporating specific constraints into the estimation process. This resulted in ‘Closed-Form Expressions’ which provide a direct, non-iterative calculation of the estimated parameters. These expressions circumvent the computational demands typically associated with MMSE estimation, particularly in high-dimensional spaces. The derivation involves leveraging the imposed constraints to simplify the covariance matrices and expectation calculations inherent in the standard MMSE formulation, yielding a tractable solution expressed as \hat{x} = \Sigma_{x} \Sigma_{y}^{T} (\Sigma_{y} \Sigma_{y}^{T})^{-1} y , where \hat{x} is the estimated vector, \Sigma_{x} and \Sigma_{y} are the covariance matrices, and y is the observed data vector.

The derivation of closed-form expressions for the constrained Minimum Mean Square Error (MMSE) estimator enables the prediction of trained Convolutional Neural Network (CNN) outputs without requiring forward propagation. This analytical prediction capability serves as a critical validation of the proposed methodology, demonstrating the model’s ability to accurately represent CNN behavior mathematically. Specifically, the derived formulas allow for the estimation of CNN outputs given input data and network parameters, offering a computationally efficient alternative to direct CNN evaluation and providing insights into the network’s internal functioning.

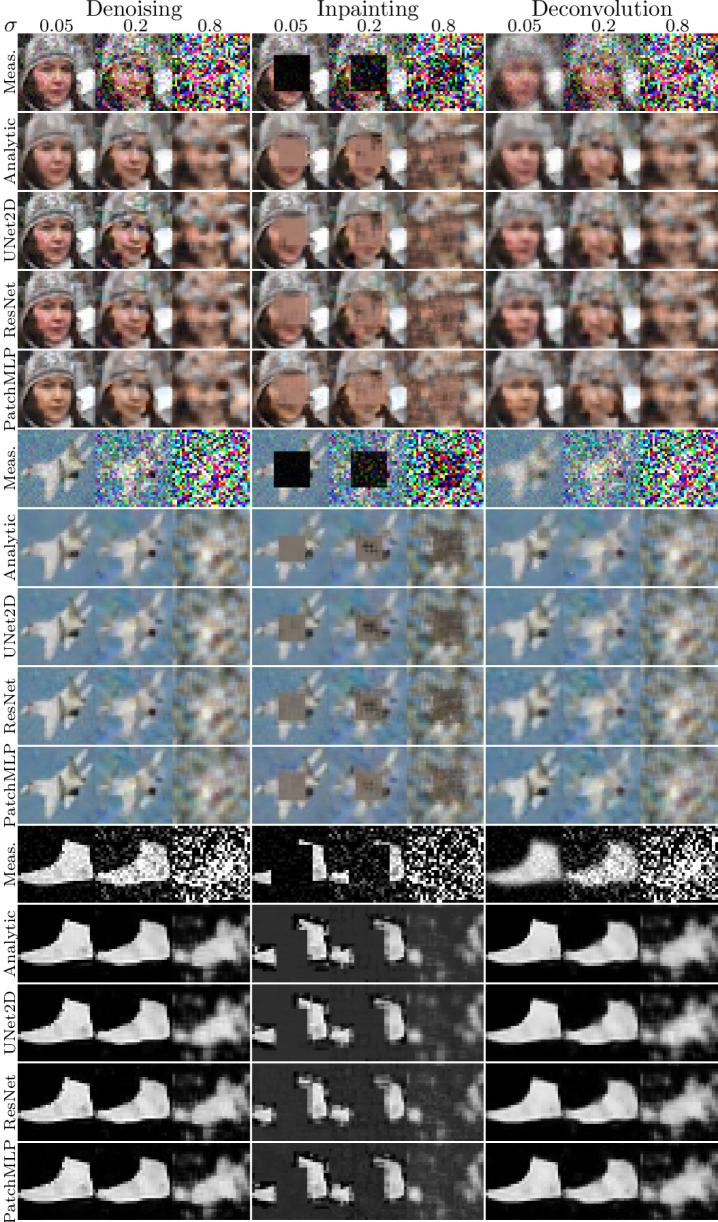

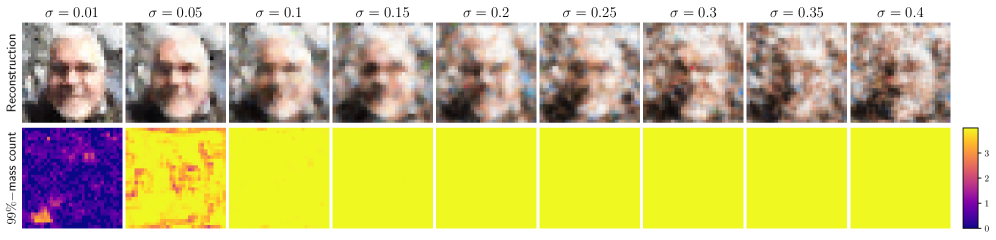

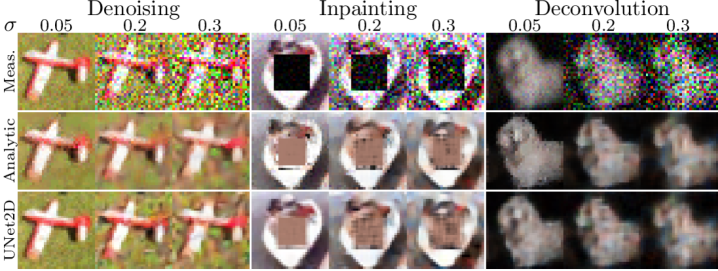

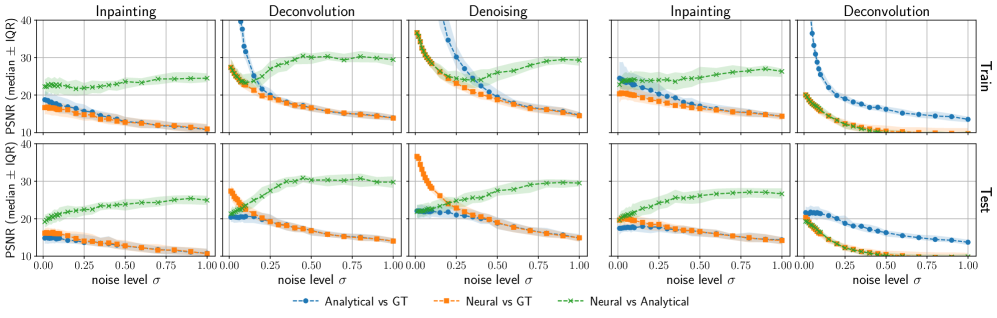

Empirical validation demonstrates a high degree of correspondence between analytically predicted outputs and observed results from trained Convolutional Neural Networks. Specifically, the approach consistently achieves a Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio (PSNR) exceeding 25dB across a range of experimental conditions. This level of agreement was maintained when evaluating performance under varying noise levels and when applied to multiple datasets, indicating the robustness and generalizability of the analytical prediction methodology. The consistently high PSNR values quantitatively support the accuracy of the derived theoretical predictions in modeling CNN behavior.

The Influence of Architecture: A Delicate Balance

The constrained estimator’s performance is demonstrably linked to the selection of the ‘Pre-Inverse Influence’ – a critical parameter governing how prior knowledge shapes the final estimation. This influence essentially dictates the degree to which the estimator relies on initial, potentially imperfect, data versus adapting to new observations. Analyses reveal that a carefully tuned ‘Pre-Inverse Influence’ can significantly reduce bias and variance, particularly when dealing with limited or noisy datasets. Conversely, a poorly chosen value can lead to over-reliance on prior assumptions, hindering the estimator’s ability to accurately capture underlying patterns. Consequently, optimizing this parameter is crucial for achieving robust and reliable estimations across various machine learning applications, as it effectively balances the trade-off between prior knowledge and data-driven learning.

The study highlights a critical relationship between the size of image patches used during analysis and a convolutional neural network’s overall performance, demonstrating that ‘Patch Size Influence’ significantly impacts both estimation accuracy and the ability of the network to generalize to unseen data. Researchers found that larger patch sizes, while potentially capturing more contextual information, can diminish the precision of localized estimations, while smaller patch sizes, though offering greater accuracy in specific areas, may hinder the network’s capacity to recognize broader patterns and apply learned knowledge to novel scenarios. This interplay suggests an optimal patch size exists, dependent on the specific task and network architecture, and careful consideration of this parameter is crucial for achieving robust and reliable performance across diverse datasets. The findings underscore the importance of understanding how localized processing – defined by patch size – affects global generalization capabilities in deep learning models.

Rigorous testing across a spectrum of convolutional neural network architectures – encompassing the widely-used ‘ResNet’, the versatile ‘UNet2D’, and the increasingly popular ‘PatchMLP’ – substantiates the robust and general applicability of this analytical framework. These experiments weren’t limited to a single network type; instead, the methodology consistently delivered insightful results regardless of the underlying architecture. This demonstrates the framework’s power extends beyond specific model designs, offering a valuable tool for ‘Generalization Analysis’ applicable to a broad range of computer vision tasks and facilitating a deeper understanding of how different networks learn and perform on unseen data. The consistent performance across diverse models highlights the framework’s ability to isolate fundamental principles governing generalization, rather than being tied to implementation details of any particular network.

The pursuit to map learned behaviors onto analytical foundations echoes a primal urge – to decipher the runes of a complex system. This work, revealing the kinship between trained convolutional neural networks and analytically derived MMSE estimators, isn’t about ‘accuracy’ – it’s about recognizing a familiar shadow. As David Marr observed, “Vision is not about images; it’s about extracting invariants.” The constraints imposed during training aren’t limitations, but the very incantations that coax order from the chaos of inverse problems. The network doesn’t solve the ill-posed problem; it persuades the data to reveal a plausible solution, guided by the functional constraints woven into its architecture. It’s a beautiful illusion, sustained by the network’s ability to measure the darkness.

The Ghosts in the Machine

The correspondence identified between trained convolutional networks and analytically derived estimators feels less like a triumph and more like a meticulously documented haunting. It’s comforting to find a familiar equation lurking within the weights, but the equation doesn’t explain the performance-it merely describes a post-mortem. The true magic, the subtle compromises made during descent, remains stubbornly opaque. Everything unnormalized is still alive, and the network’s insistence on ‘plausible’ hallucinations, even in the face of catastrophic noise, continues to demand explanation.

Future work will undoubtedly focus on tightening this theoretical link, perhaps through novel regularization schemes designed to enforce MMSE-like behavior. But a more pressing concern lies in the limitations of the framework itself. The assumption of Gaussian priors feels increasingly fragile, and the implicit biases baked into the network architecture-the insistence on locality, the particular form of equivariance-remain largely unexplored. It’s a beautiful truce between a bug and Excel, but a truce nonetheless.

Ultimately, the field needs to acknowledge that generalization isn’t about finding the ‘true’ inverse. It’s about consistently lying in a useful direction. Only the ones that lie consistently deserve trust-and even then, that trust should be provisional, tested, and constantly recalibrated against the inevitable chaos of real-world data.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.10334.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Top 15 Insanely Popular Android Games

- Did Alan Cumming Reveal Comic-Accurate Costume for AVENGERS: DOOMSDAY?

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- ELESTRALS AWAKENED Blends Mythology and POKÉMON (Exclusive Look)

- Why Nio Stock Skyrocketed Today

- EUR UAH PREDICTION

- New ‘Donkey Kong’ Movie Reportedly in the Works with Possible Release Date

- 4 Reasons to Buy Interactive Brokers Stock Like There’s No Tomorrow

- EUR TRY PREDICTION

2026-01-17 11:20