As a devoted music enthusiast, I’ve noticed that every new chapter in the evolving story of music history seems to spark debates about genre definitions and emergence points, particularly with hip-hop. Interestingly enough, much of its roots were laid down beyond the confines of the mainstream music industry. It wasn’t until the late ’70s that this unique musical style truly started making its mark.

In today’s music scene, the origins of rap remain a topic of ongoing interest due to its widespread popularity. However, I often find that attempts to pinpoint a specific person or location as the birthplace of rap oversimplify the complex cultural history behind this art form, particularly within the African diaspora. A simplified origin story may provide a clean and tidy starting point for telling the story, but it fails to capture the rich tapestry of the diverse communities that nurtured the development of rapping and rhythmic speech.

This article likely won’t provide a comprehensive response to the question at hand. Instead, it might help illustrate how exploring the origins of rap within hip-hop could benefit from letting go of the search for a simple, definitive answer. Instead, one should appreciate the intricacies involved.

Where did you get that rap from?

In a nutshell, when it comes to discussing the beginnings of rap music, I think it’s crucial to acknowledge that certain fundamental aspects of the genre are common among multiple artists. While individual creativity is indeed significant, it’s equally important to consider how the broader rap community contributes to its evolution and growth.

During the 1970s, when hip-hop was still new, there has been a lot of conversation about how rapping came into being. Often, when people recount the early parties hosted by DJ Kool Herc, they highlight his knowledge of Jamaican sound systems and toasting, given that he hailed from Kingston.

In JayQuan’s Hip-Hop Historian video, he provides an insightful analysis of the “Golden Era,” highlighting that Grandmaster Flash (Herc) often spoke, sometimes rhythmically, over break beats.

For an illustration of this toasting style, consider the phrase ‘This Station Rules the Nation,’ originating from around 1970. This song showcases the innovative skills of U-Roy, who freestyles over the backing track, or ‘version,’ of ‘Love Is Not A Gamble,’ a song by the rocksteady group the Techniques, which I believe was released in 1967.

As a music enthusiast with a soft spot for Jamaican beats, I’ve learned that they often call those foundational rhythm tracks “riddims.” One legendary riddim that’s been making waves is the Stalag 17 riddim, initially created by Ansel Collins back in ’73. This instrumental track has been toasted over by legendary artists like Sister Nancy and Tenor Saw, and it continues to inspire new generations of musicians today. It’s much like how early hip-hop artists would use the same break beats as a canvas to paint their rhymes on.

According to Darby Wheeler and Rodrigo Bascunan’s docuseries Hip-Hop Evolution (2016), Kool Herc’s sound system not only boosted the bass in the music, but also allowed him to create an echo effect on his voice, much like U-Roy did on tracks such as “This Station Rules the Nation.” This innovation was similar to early dub music produced by engineers and producers like King Tubby and Lee “Scratch” Perry during that period.

In a style reminiscent of Jamaican toasting, figures such as Herc and MC Coke La Rock would frequently talk over the breakbeats, occasionally using this platform to offer shout-outs or announcements, even commenting humorously on situations like someone parking their car illegally.

As time passed, MCs like La Rock began using the microphone with intention to rap along with the beats that Herc was spinning. This marked the beginning, or so the tale often goes in this culture, of the rise of early rappers.

Delving into the initial gatherings in the Bronx provides a crucial viewpoint for grasping the influence of MCs close to Kool Herc. Yet, my curiosity often lies in uncovering specific details about when and how rapping or rhyming as we know it today originated.

The narrative hints at the guests at Herc’s parties adopting a style of speaking that included rhymes and rhythmic speech, often associated with rap music. However, it doesn’t provide a comprehensive account of how this style originated or precisely what was being rapped during that time, particularly focusing on those who were influential within the era.

The roots of rap might not have solely emerged from within the early days of hip-hop in the Bronx, as I suspect. Instead, rapping could have been a response to existing trends outside the hip-hop culture, which then adapted and integrated into the growing hip-hop scene.

During the early days of hip-hop in the 1970s in New York City, numerous DJs and MCs often credit radio personalities like Frankie Crocker, Hank Spann, and Gary Byrd for their impact. These disc jockeys stood out due to their use of rhythmic and rhyming speech on air.

This is often referred to as “rapping” or simply possessing a “rap.” It originated from renowned DJs like Philadelphia-born Douglas “Jocko” Henderson, who not only worked in Philadelphia but also in New York and Baltimore.

This is called rapping or having your own style of rapping. This style was passed down by famous DJs such as Jocko Henderson, who is originally from Philadelphia and has worked in cities like New York and Baltimore.

In the evolution of black music, the cool rap style of these radio DJs was strongly influenced by the eloquence and rhythmic speech of jump blues and early rhythm and blues musicians like Louis Jordan, as well as jazz legends such as Cab Calloway, whose wit and style were immortalized in numerous jive dictionaries since approximately the late 1930s.

In my recent write-up about the topic of nostalgic rap music, it’s worth mentioning that comedians like Pigmeat Markham and Rudy Ray Moore were also well-known figures who dabbled in rapping as well.

Kool Herc drew inspiration from Jamaican toasting traditions, whereas Moore frequently delivered African American toasts, including “Shine and the Titanic,” often called “jail toasts” due to their popularity among incarcerated black men during the early to mid-20th century, as a form of spoken word culture that thrived within the black prison community.

As a devoted fan, I can’t help but share an exciting revelation about Hollywood, the legendary New York DJ. In a captivating interview with Mark Skillz for Medium, he reminisced about his illustrious career, which began in 1975. Drawing inspiration from musical icons like Frankie Crocker, Hank Spann, and Rudy Ray Moore, Hollywood sought to blend his own singing background with their distinctive styles.

One of his first creations was a clever reinterpretation of Isaac Hayes’ lyrics from “Good Love 6-9969” off the Black Moses album (1971). He beautifully wove these words into the breakdown at the end of MFSB’s “Love Is The Message,” creating a unique and memorable blend of two iconic tracks.

In the ’70s, the poetic expressions of the Black Power movement resonated strongly with both black music and comedy scenes. Groups like the Watts Prophets coined the term “rapping” for this kind of poetry, which would significantly shape what early hip-hop artists and those who followed had to say once they got a chance to speak through a microphone.

In that period, poets and activists like Jesse Jackson held significant influence not just through their poetic messages but also as models for inspiring crowds and encouraging audience involvement. In fact, Jackson’s iconic “I am! Somebody” performance served as a blueprint for others, such as Chief Rocker Busy Bee, who would mimic the call-and-response style when performing with the crowd.

In a similar vein, the Busy Bee adopted a braggadocious demeanor, modeled on Muhammad Ali, and employed rhythmic banter with Drew Bundini Brown, much like Ali did with his corner men.

Jalal Mansur Nuriddin, a member of the black poetry group The Last Poets, who often inspire hip-hop artists, released his own album titled “Hustlers Convention” in 1973 under the name Lightn’ Rod. This narrative album was designed in the style of jail toasts, similar to the performances by comedians like Rudy Ray Moore and characters such as Iceberg Slim.

The track “Hustlers Convention,” from the album with the same name by Grandmaster Melle Mel and the Furious Five, has been frequently cited by various generations of hip-hop MCs as a significant influence.

Essentially, the song is a remake of the opening track from Hustlers Convention, originally played by Kool & The Gang. This instrumental was later used in the Jungle Brothers and Q-Tip’s “Black Is Black,” a song from their debut album Straight Out The Jungle, released in 1988.

1988 saw Ice-T, whose moniker reflects his admiration for influential figures like Iceberg Slim, mentioning the Hustlers Convention in his song “Soul on Ice”, which was the penultimate track on his second album named “Power”.

Or more concisely:

Ice-T, inspired by figures such as Iceberg Slim, referenced the Hustlers Convention in his 1988 song “Soul on Ice” on his sophomore album “Power”.

In simpler terms, I wanted to provide these examples as background information to demonstrate that various styles of rap or early forms of it had already gained recognition within the African American community in New York and broader black communities globally during the emergence of hip-hop in the 1970s.

As a devoted fan, I can’t help but marvel at how hip-hop continually pushes boundaries while still building upon its rich heritage. It’s this unique blend of innovation and respect for tradition that I think sets the genre apart.

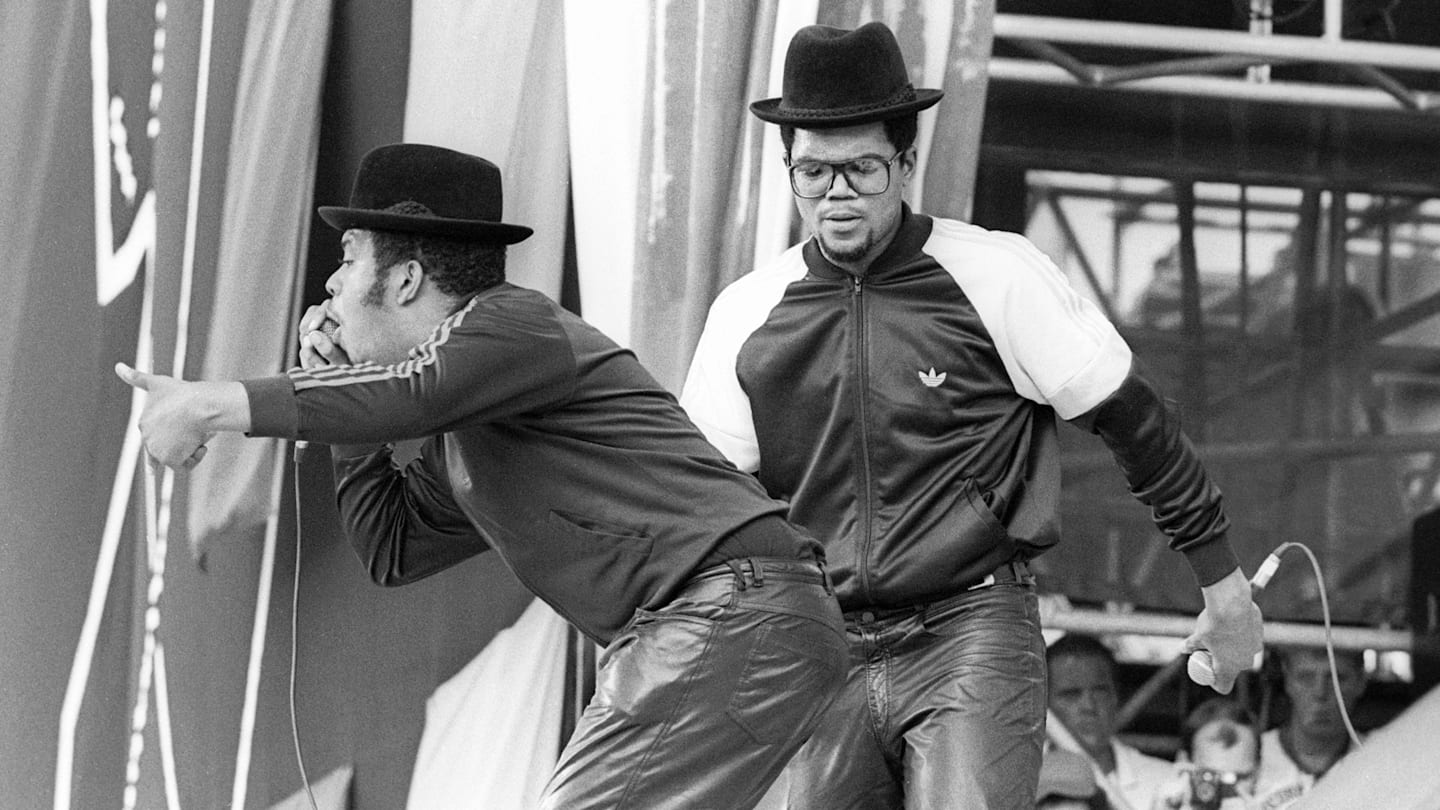

The tradition of influence being handed down within hip-hop, dating back through generations, can also be considered a form of innovation. To grasp my argument, just listen to Run from Run-DMC starting the group’s name at the beginning of “Rock Box,” released in 1984. Since then, his unique voice has been frequently imitated and referenced, making it an enduring element within hip-hop culture.

In this context, J Dilla took the song “Run” by the Pharcyde and used it as a basis for his own track titled “Runnin'”. Redman, on the other hand, imitated that very same song in the second verse of “Pick It Up”. Jay-Z also makes a reference to this song at the beginning of the first verse in “Where I’m From.” In simpler terms, all three artists have referenced or sampled the original “Run” song by the Pharcyde in their respective tracks.

In my view, it’s not just individuals but largely the community that has played a crucial role in passing rap music down to the current hip-hop generation, and I think this significance is likely to persist for future generations who will primarily find their source of rapping within hip-hop culture.

Read More

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Brown Dust 2 Mirror Wars (PvP) Tier List – July 2025

- Banks & Shadows: A 2026 Outlook

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- HSR 3.7 story ending explained: What happened to the Chrysos Heirs?

- ETH PREDICTION. ETH cryptocurrency

- The Weight of Choice: Chipotle and Dutch Bros

- The Best Actors Who Have Played Hamlet, Ranked

- Uncovering Hidden Groups: A New Approach to Social Network Analysis

2025-08-23 15:00