The current obsession with ‘disruption’ and ‘innovation’ in the financial markets is, naturally, rather tiresome. One is reminded of the late, lamented days of the railways, when every prospectus promised a utopian future and delivered, more often than not, a diluted shareholding and a sense of vague disappointment. Still, even the most jaded observer must concede that Nvidia, for all its attendant hype, presents a slightly less egregious case. The company, it appears, actually makes things, and those things are, for the moment, in demand.

Investing, one supposes, is the art of transferring money from the impatient to the patient. Or, failing that, from the less informed to the slightly more informed. A paltry two hundred dollars, of course, buys little enough these days – barely a decent bottle of claret – but it is, at least, a start. A gesture, if you will, towards fiscal responsibility. Or, more accurately, a calculated gamble.

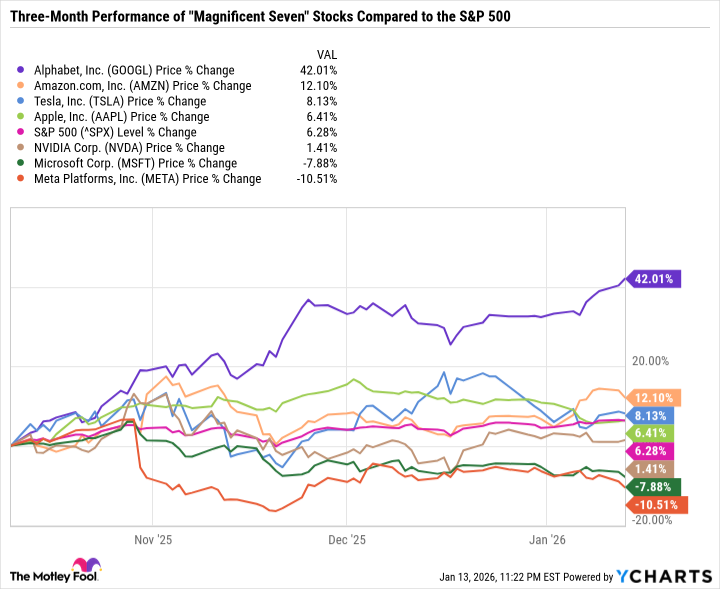

Nvidia, currently trading around $186 per share, is not, admittedly, a bargain. But then, bargains are rarely to be found in sectors experiencing quite so much breathless enthusiasm. The recent underperformance compared to the so-called ‘Magnificent Seven’ – a rather vulgar appellation, if one may say so – is, in fact, something of a relief. It suggests a degree of rationality, however fleeting, has returned to the market. Microsoft and Meta Platforms, one observes, have fared no better in recent months, a fact that should give pause to the more excitable investors.

The announcement at CES regarding the Rubin architecture – named, with a commendable lack of modesty, after the astronomer Vera Rubin – is, on the surface, merely a technical upgrade. But it is the scale of the upgrade that is noteworthy. Six integrated chips, designed to address the bottlenecks inherent in artificial intelligence applications, are a substantial undertaking. The company’s commitment to rack-scale integration – a rather dreary phrase, but one that implies a degree of foresight – suggests they are not simply selling hardware, but solutions. The promise of five-fold improvements in inference power, while undoubtedly optimistic, is at least a departure from the usual marketing hyperbole.

The relentless pursuit of Moore’s Law – that comforting, if increasingly strained, prediction of ever-increasing transistor density – continues apace. Rubin boasts 60% more transistors than its predecessor, Blackwell, which is, in its way, impressive. But the true innovation lies not in simply cramming more components onto a chip, but in designing a system that actually works. Nvidia’s ability to cannibalize its own product lines – a trait one generally associates with more ruthless organizations – is a testament to its long-term vision. Or, perhaps, simply a matter of good accounting.

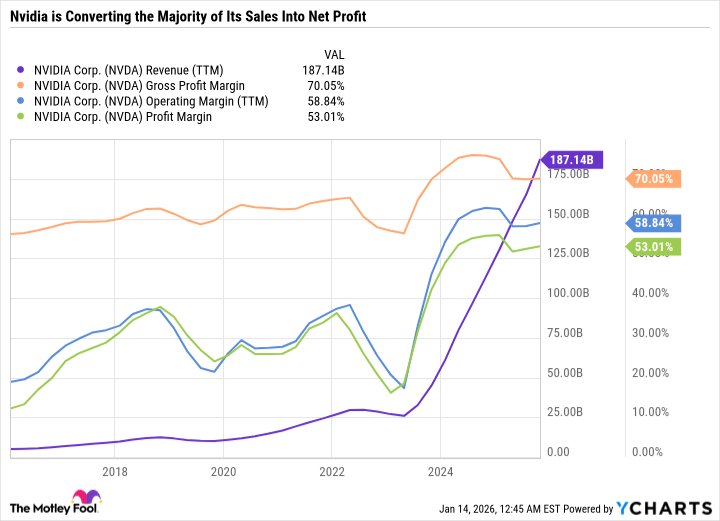

The company’s profitability is, frankly, astonishing. Converting 70 cents of every dollar in sales into gross profit, and 53 cents into after-tax net profit, is a feat rarely encountered outside the realms of tax avoidance and illicit trade. The inevitable competition from AMD and Broadcom is, of course, a concern. But Nvidia’s margins are so substantial that it can afford to weather a considerable amount of turbulence.

The current price-to-earnings ratio of 45.9 may seem steep, but the consensus estimates for fiscal 2027 suggest a more reasonable valuation of 24.4. If Rubin performs as advertised, those estimates could prove to be conservative. And, in the current climate, one should always be wary of underestimation.

To describe Nvidia as a ‘growth stock’ is, perhaps, to state the obvious. But it is a growth stock that is actually growing. And, in a market awash with speculation and empty promises, that is a distinction worth noting. A modest investment of two hundred dollars may not secure one’s financial future, but it is, at the very least, a marginally less foolish endeavor than most.

Read More

- Top 15 Insanely Popular Android Games

- Did Alan Cumming Reveal Comic-Accurate Costume for AVENGERS: DOOMSDAY?

- Gold Rate Forecast

- ELESTRALS AWAKENED Blends Mythology and POKÉMON (Exclusive Look)

- EUR UAH PREDICTION

- New ‘Donkey Kong’ Movie Reportedly in the Works with Possible Release Date

- Core Scientific’s Merger Meltdown: A Gogolian Tale

- Why Nio Stock Skyrocketed Today

- 4 Reasons to Buy Interactive Brokers Stock Like There’s No Tomorrow

- The Weight of First Steps

2026-01-17 15:53