Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new machine learning approach accurately estimates traffic density using only limited probe vehicle data, offering a powerful solution for real-time traffic monitoring.

This review details a method that bridges microscopic and macroscopic traffic models to achieve accurate density estimation without explicit conservation law enforcement.

Accurate traffic flow modeling often requires extensive datasets, presenting a challenge when data collection is limited. This paper, ‘Traffic Flow Reconstruction from Limited Collected Data’, introduces a novel machine learning approach to estimate traffic density using only initial and final positions of a sparse set of probe vehicles. By leveraging the theoretical convergence between microscopic dynamical systems and established macroscopic traffic models, the proposed method achieves robust density estimation without explicitly enforcing conservation laws. Could this technique unlock more efficient traffic management strategies with minimal reliance on comprehensive data collection?

Foundations of Traffic State: Understanding the System

The ability to accurately characterize ‘Traffic State’ – encompassing the number of vehicles (

The fundamental relationship between traffic density and velocity, often encapsulated by the concept of Greenshields Velocity, is central to understanding how traffic behaves. This principle posits an inverse, non-linear connection: as vehicle density increases, the average speed of traffic initially decreases rapidly, then plateaus as congestion intensifies.

The prevailing conditions at the outset of traffic flow – specifically, the ‘Initial Density’ of vehicles – exert a disproportionate influence on subsequent patterns and behaviors. Research demonstrates that even slight variations in this starting density can lead to dramatically different outcomes, ranging from smooth, uncongested flow to the rapid formation of shockwaves and stop-and-go traffic.

From Macro to Micro: Modeling the Flow of Traffic

Macroscopic traffic models treat vehicular flow as a continuous fluid, analogous to water or gas, and are therefore governed by the principles of conservation laws. These laws-specifically, the conservation of vehicles, momentum, and energy-are expressed mathematically as partial differential equations that describe changes in traffic density, velocity, and spacing over time and distance. By applying these equations, engineers can analyze traffic patterns and predict congestion based on overall flow rates and roadway capacity, without needing to track individual vehicles. This simplification allows for efficient computation and analysis of large-scale traffic networks, though it inherently sacrifices the ability to model nuanced driver behaviors or specific vehicle interactions.

Microscopic traffic models simulate the movement of individual vehicles, each possessing attributes like position, velocity, and driver behavior parameters. This contrasts with macroscopic models which treat traffic as a continuous flow. While offering a higher level of detail and the potential to capture emergent behaviors arising from individual vehicle interactions, microscopic simulations are significantly more computationally demanding. The processing requirements scale directly with the number of vehicles simulated, necessitating high-performance computing resources and optimized algorithms for realistic and timely results. Parameters governing individual vehicle behavior-such as car-following models, lane-changing logic, and reaction times-are typically calibrated using empirical data from real-world traffic observations.

Traffic flow models, both macroscopic and microscopic, require empirical validation through data gathered from probe vehicles. These vehicles, equipped with GPS and data logging capabilities, continuously transmit positional and velocity information as they traverse roadways. This real-world data is then compared against model predictions, allowing researchers to identify discrepancies and adjust model parameters – such as speed limits, driver reaction times, and roadway capacities – to improve accuracy. The process involves statistically analyzing the collected data to calibrate model outputs against observed traffic patterns, ensuring the models effectively represent actual traffic behavior and can reliably forecast future conditions. Data from diverse sources, including both privately owned and fleet vehicles, are often aggregated to enhance the robustness and generalizability of the model calibration process.

Reconstructing Traffic Density: A Data-Driven Perspective

The reconstruction of traffic density utilizes an optimization problem formulated to estimate final density distributions from limited sensor data. This mathematical framework defines an objective function – minimizing the discrepancy between predicted densities and available measurements – subject to constraints ensuring physical plausibility of the reconstructed field. The optimization process leverages techniques such as

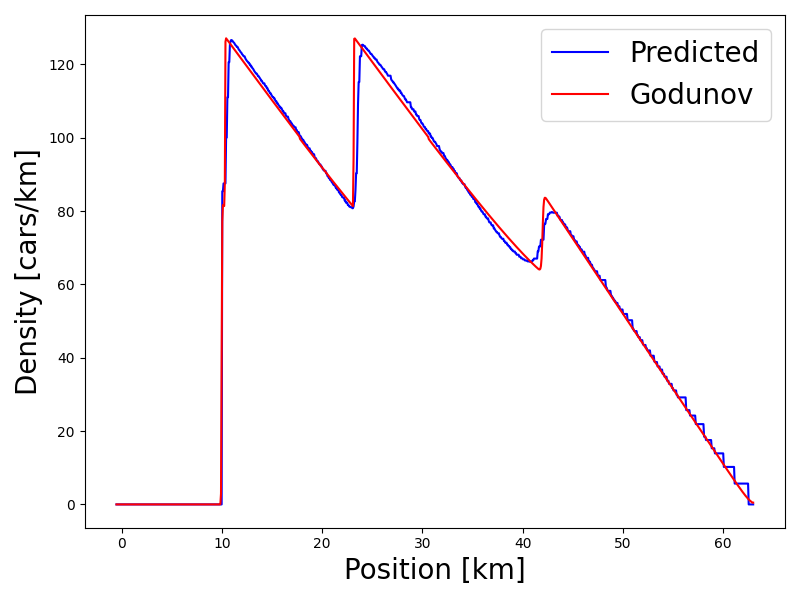

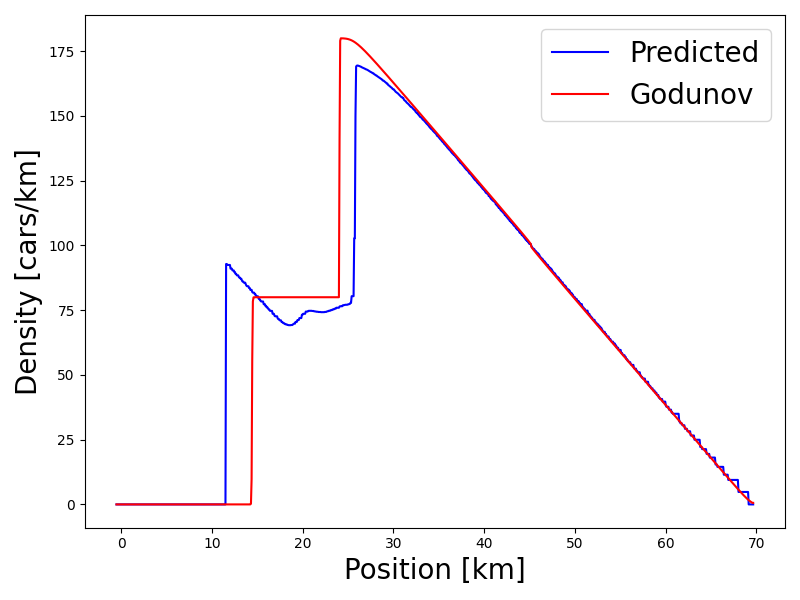

The traffic density reconstruction process was evaluated using Mean Squared Error (MSE) as a performance metric. Initial testing, conducted with a probe vehicle count of N=2000 and a time step of T=0.1, yielded an MSE of 0.0483. Subsequent testing with an increased probe vehicle count (N=4000) and a larger time step (T=0.2) demonstrated improved accuracy, resulting in a significantly lower MSE of 0.0076. These results indicate a clear correlation between increased data density and temporal resolution with the precision of the reconstructed traffic density distributions.

Traffic density reconstruction utilizes data gathered from probe vehicles to estimate comprehensive traffic flow patterns where direct measurement is unavailable. Model performance, assessed via Relative Error (RE), indicates a high degree of accuracy; with a probe vehicle sample size of N=2000 and a time step of T=0.1, the RE is 0.0053. Increasing the sample size to N=4000 and the time step to T=0.2 further improves accuracy, yielding a RE of 0.0020. These results demonstrate the model’s capacity to effectively infer traffic conditions from limited data sources.

Validating Model Convergence: Measuring Predictive Power

The convergence of a reconstructed probability distribution, such as the ‘Final Density’ representing traffic flow, isn’t easily judged by simple visual inspection. Instead, researchers employ the Wasserstein Distance – also known as the Earth Mover’s Distance – a metric that quantifies the minimum ‘cost’ of transforming one probability distribution into another. Imagine one distribution as a pile of earth and the other as a hole; the Wasserstein Distance calculates the least amount of ‘work’ needed to fill the hole with the earth. This is particularly valuable when dealing with complex systems like traffic, where subtle shifts in density can significantly impact flow. By minimizing the Wasserstein Distance between the model’s reconstructed density and the actual observed density, scientists can rigorously validate model accuracy and ensure reliable predictions about traffic patterns, ultimately leading to more effective traffic management solutions.

The accurate modeling of shock waves – those abrupt disruptions in traffic flow often stemming from incidents or sudden braking – represents a significant advancement in traffic prediction. A well-validated model doesn’t simply forecast average traffic density; it anticipates these localized, yet impactful, events. By capturing the formation, propagation, and dissipation of shock waves, the system provides a more nuanced and realistic simulation of traffic dynamics. This capability allows for proactive interventions, such as adjusted speed limits or rerouting suggestions, minimizing the cascading effects of congestion and improving overall network resilience. The model’s ability to foresee these transient disruptions distinguishes it from simpler approaches and offers a pathway towards truly intelligent transportation systems.

The demonstrated gains in model accuracy, evidenced by mean squared error (MSE) values of 0.0483 and 0.0076 alongside relative errors (RE) of 0.0053 and 0.0020, represent a significant step toward optimized traffic flow. These metrics confirm the model’s ability to accurately predict traffic dynamics, directly enabling the development of proactive traffic management strategies. Consequently, road operators can leverage these predictions to implement real-time adjustments – such as dynamic speed limits or optimized signal timings – minimizing congestion and improving overall network efficiency. Beyond simply easing commutes, this heightened accuracy contributes to substantial safety benefits by anticipating and mitigating potential bottlenecks, reducing the risk of secondary incidents, and ultimately fostering a more secure environment for all road users.

The presented work elegantly addresses the challenge of reconstructing macroscopic traffic states from sparse data. It recognizes that overly complex models, while potentially capturing nuanced behavior, often fail to scale effectively. This mirrors a core tenet of robust system design – simplicity is paramount. As Werner Heisenberg observed, “The very act of observing alters that which we observe.” Similarly, attempting to directly enforce every conservation law within the reconstruction process introduces computational rigidity. Instead, the model implicitly learns these principles through data, resulting in a more adaptable and scalable solution. This approach acknowledges that good architecture is invisible until it breaks; the model’s success lies in its ability to accurately estimate density without explicitly codifying every underlying constraint.

What Lies Ahead?

The apparent success of this approach – inferring the complex from the minimal – should give pause. If the system looks clever, it probably is fragile. The method sidesteps explicit enforcement of conservation laws, which, while computationally convenient, feels…unsatisfactory. Nature rarely permits such elegant omissions. Future work must address whether this lack of explicit physical constraint introduces systematic errors, particularly in scenarios involving complex topology or aggressive driver behavior. A system built on implicit assumptions will inevitably reveal the limits of those assumptions.

The convergence of macroscopic and microscopic models is, of course, not new. However, this work highlights the potential for machine learning to act as a bridge, not merely an emulator. The true test will lie in extending this framework beyond density estimation. Can it reconstruct behavior? Predicting not just where traffic is, but where it will be, and, crucially, why? That demands a more nuanced understanding of the underlying generative processes, not simply a skillful interpolation between known states.

Architecture, after all, is the art of choosing what to sacrifice. This work has sacrificed explicit physical modeling for computational efficiency. Whether that trade-off proves sustainable remains to be seen. The next step isn’t simply more data, or larger networks. It’s a deeper consideration of what fundamental principles can – and perhaps should – be reintroduced into the system, even at a computational cost.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11336.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Silver Rate Forecast

- DOT PREDICTION. DOT cryptocurrency

- Securing the Agent Ecosystem: Detecting Malicious Workflow Patterns

- 4 Reasons to Buy Interactive Brokers Stock Like There’s No Tomorrow

- NEAR PREDICTION. NEAR cryptocurrency

- EUR UAH PREDICTION

- Did Alan Cumming Reveal Comic-Accurate Costume for AVENGERS: DOOMSDAY?

- Top 15 Insanely Popular Android Games

- USD COP PREDICTION

2026-02-14 06:12