Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research applies the tools of differential geometry to understand how information travels within neural networks, offering a fresh perspective on network architecture and optimization.

This review details a novel methodology using Ricci curvature and graph theory to analyze data flow within neural networks, potentially enabling more effective pruning and improved network performance.

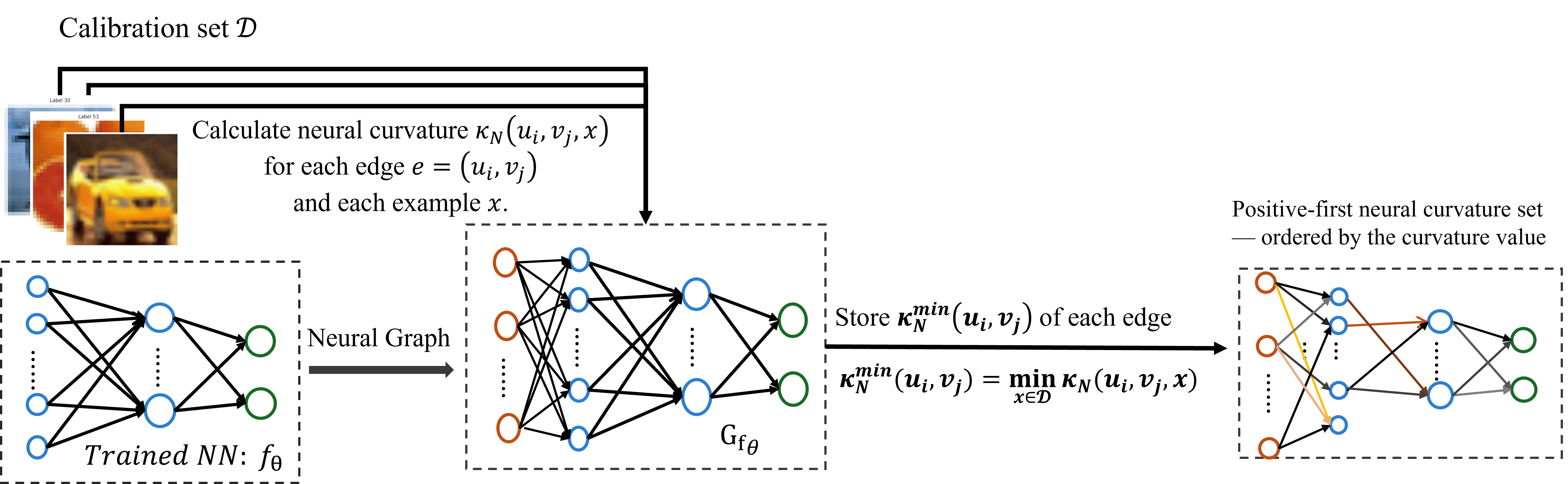

Understanding the functional importance of connections within deep neural networks remains a key challenge despite their widespread success. This paper, ‘Analyzing Neural Network Information Flow Using Differential Geometry’, introduces a novel approach to this problem by framing neural networks as graphs and leveraging concepts from differential geometry, specifically Ollivier-Ricci curvature, to quantify edge criticality. The authors demonstrate that edges with negative curvature act as bottlenecks in information flow, and their removal significantly degrades network performance, while positive-curvature edges are largely redundant. Could this geometric perspective unlock more effective pruning strategies and ultimately lead to more interpretable and robust neural network architectures?

Deconstructing the Network: The Illusion of Scale

Contemporary neural networks achieve remarkable performance through sheer size, often incorporating millions or even billions of interconnected parameters. However, a substantial portion of these connections are frequently redundant, contributing little to the network’s overall predictive power. This over-parameterization leads to significant computational inefficiencies, demanding substantial memory and processing resources during both training and inference. The excess connections not only inflate model size but also increase the risk of overfitting, where the network memorizes training data rather than generalizing to new examples. Consequently, reducing this redundancy is critical for deploying these powerful models on devices with limited capabilities, like smartphones or embedded systems, and for accelerating their operation in data centers where energy consumption is a major concern.

Early attempts to streamline neural networks through connection pruning often resulted in a frustrating trade-off: substantial reductions in model size were frequently accompanied by a significant drop in accuracy. These traditional methods typically relied on simple heuristics – removing connections with low weight magnitude or randomly discarding a percentage of parameters – without considering the complex interplay between different parts of the network. Consequently, important connections vital for maintaining performance were often inadvertently severed, leading to a phenomenon known as ‘catastrophic forgetting’ or a general decline in the model’s ability to generalize to new data. This limitation underscored the need for more sophisticated pruning strategies capable of discerning truly redundant connections from those critical for preserving the network’s representational power and predictive capabilities.

The escalating demand for artificial intelligence on edge devices – smartphones, wearables, and embedded systems – necessitates a fundamental shift in neural network design. While increasingly complex models achieve state-of-the-art performance, their substantial computational requirements and memory footprint often preclude deployment on these resource-constrained platforms. Consequently, research focuses intensely on developing sophisticated pruning techniques that selectively remove unimportant connections within a network, drastically reducing its size and computational load without sacrificing critical accuracy. These ‘smarter’ methods move beyond simple magnitude-based pruning, instead leveraging information theory, gradient sensitivity analysis, or even reinforcement learning to identify and preserve the connections most vital to the network’s overall function. The successful implementation of such techniques promises to unlock the full potential of AI, extending its reach beyond powerful servers and into the ubiquitous realm of everyday devices.

Existing Approaches: The Limits of Simplification

Magnitude-based pruning operates by removing connections within a neural network based on the absolute value of their corresponding weights; this approach prioritizes simplicity in implementation. However, this method disregards the functional significance of individual weights, potentially eliminating connections critical to network performance. A small weight may contribute significantly to the output for specific inputs, and its removal, despite its size, can lead to substantial accuracy loss. Consequently, magnitude-based pruning often requires lower pruning rates compared to more sophisticated techniques to maintain acceptable performance levels, limiting its potential for model compression and efficiency gains.

Sensitivity-based pruning methods, such as SNIP (Sparse Neural Network via Importance Weighted Pruning) and SynFlow, move beyond magnitude-based approaches by evaluating the impact of removing individual connections on the overall loss function. SNIP approximates this sensitivity using the first-order Taylor expansion of the loss with respect to each weight, effectively estimating the change in loss resulting from pruning. SynFlow, conversely, calculates sensitivity based on the product of the gradient of the loss with respect to a weight and the weight itself, providing an alternative metric for importance. Both techniques aim to identify and retain connections that contribute significantly to minimizing loss, thereby preserving network performance more effectively than simply removing small-magnitude weights. These methods require calculating gradients or approximations thereof, adding computational overhead compared to magnitude-based pruning, but offer improved sparsity-accuracy trade-offs.

Sensitivity-based pruning methods, such as SNIP and SynFlow, while representing advancements over simple magnitude-based approaches, fundamentally estimate the importance of network parameters using first-order Taylor approximations of the loss function. This reliance on first-order approximations means these methods evaluate the change in loss due to infinitesimal perturbations of weights, potentially overlooking higher-order interactions and synergistic effects between parameters. Consequently, the true impact of removing a weight – which may only become apparent when considering its interplay with other weights – can be miscalculated, leading to the retention of less critical connections or the removal of important, but subtly interacting, parameters. This limitation restricts their ability to accurately assess the full functional role of individual weights within the broader network context.

The Network as a Landscape: Unveiling Hidden Geometry

Representing a neural network as a graph allows for the application of Graph Theory principles to analyze its structure and function. In this model, neurons become nodes and the weighted connections between them become edges. This facilitates the use of established graph-theoretic metrics – such as degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and clustering coefficient – to assess neuron importance and network connectivity patterns. Furthermore, spectral graph theory can be employed to analyze the network’s overall properties, including its stability and ability to propagate information. Analyzing the network as a graph shifts the focus from individual neuron behavior to the collective properties of the interconnected system, providing a holistic view of information flow and potential bottlenecks.

Ricci curvature, originating in differential geometry as a measure of how a volume changes in a given space, has been adapted for use in analyzing neural networks represented as graphs. In this context, edges – representing connections between neurons – are assigned a curvature value based on the network’s geometry and the flow of information. Specifically, the curvature at an edge is calculated by examining the aggregate effect of neighboring edges on the resistance between nodes; higher curvature indicates a less critical connection, while lower curvature suggests an edge vital for maintaining overall network connectivity and information propagation. The adapted metric effectively quantifies the influence of each edge on the network’s global structure, allowing for the identification of both bottlenecks and redundant connections. The formula, adapted from its geometric origins, considers the average resistance change resulting from removing the edge and its immediate neighbors – a lower value signifying greater importance k_i = \frac{1}{n}\sum_{j=1}^{n} R(G - e_i - e_j), where k_i is the curvature of edge i, and R represents the effective resistance.

Edges with low Ricci curvature within a neural network graph represent connections that significantly impact information propagation. Quantitatively, low curvature indicates that removing a given edge would disproportionately increase the shortest path lengths between numerous node pairs, thereby disrupting data flow. These edges function as “bottlenecks” or critical pathways, as information must traverse them to connect different parts of the network. Identifying these low-curvature edges allows for targeted analysis of network robustness; their failure or degradation would likely result in substantial performance decline. Furthermore, this approach provides a mechanism for pruning less important connections without significantly impacting overall network functionality, potentially leading to more efficient and streamlined models.

Mapping Importance: Quantifying Curvature in the Network

Direct computation of Ricci curvature, a measure of a manifold’s geometry, presents significant computational challenges, particularly when applied to the high-dimensional parameter spaces of neural networks. Ollivier-Ricci curvature offers a discrete approximation that addresses this limitation by estimating curvature from sampled data points. This approach replaces continuous calculations with finite, empirically-derived values, making it feasible to assess curvature across the numerous connections within a neural network.

Ollivier-Ricci curvature approximation utilizes concepts from Information Theory to quantify the dissimilarity between probability distributions representing the local geometry of a neural network. Specifically, it employs the Wasserstein distance – a metric measuring the distance between probability distributions – between the points themselves and its neighbors, thereby providing a tractable method for curvature analysis in discrete settings like those found in neural network architectures.

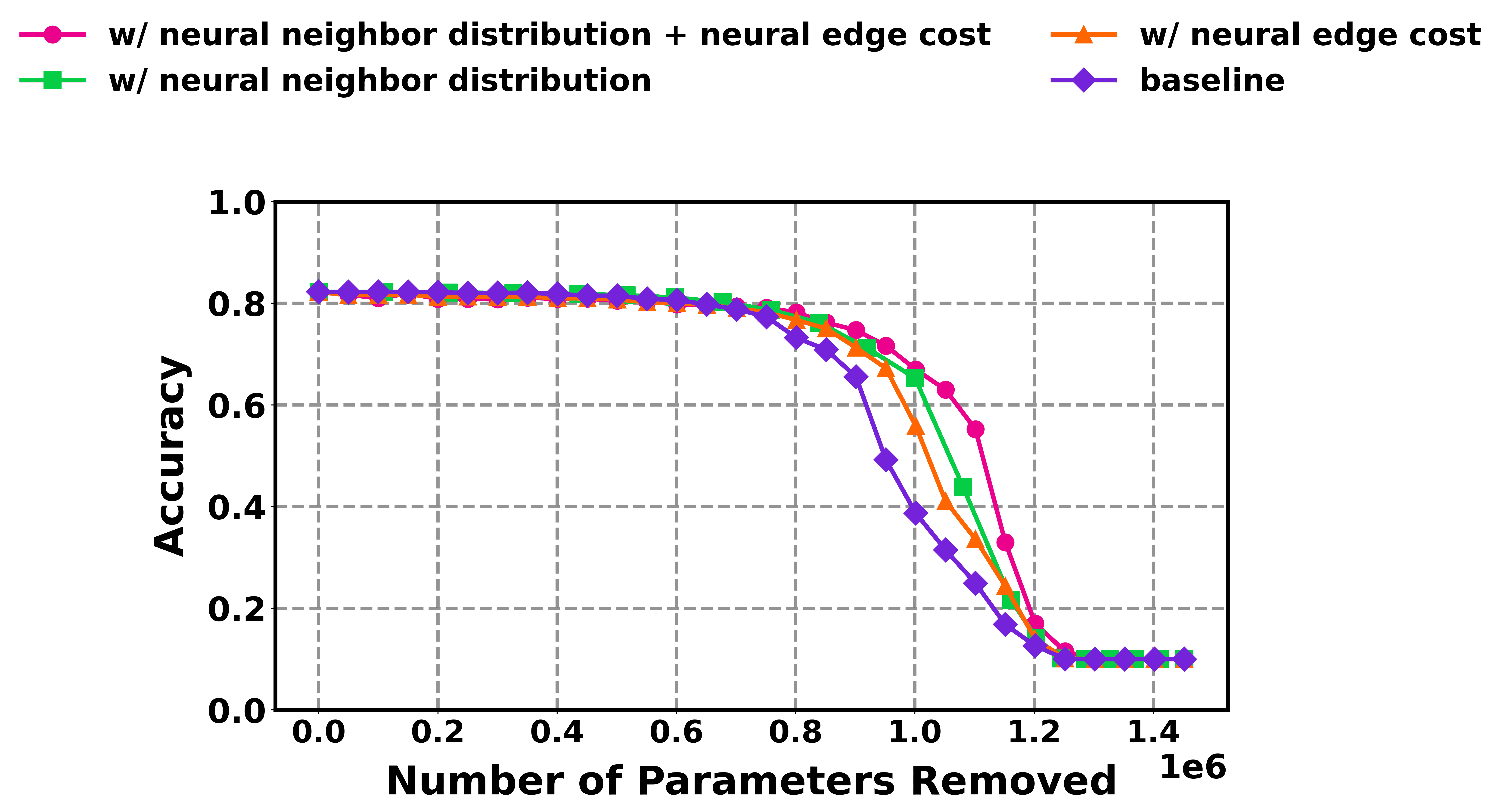

Neural curvature scores are computed by applying Ollivier-Ricci curvature – an approximation of Ricci curvature – to the weight matrices of a neural network. This process involves estimating the Wasserstein distance – also known as the Earth Mover’s Distance W(P, Q) – between probability distributions representing the network’s input and output data for each connection. A higher curvature score indicates a greater influence of that connection on the network’s loss function; conversely, connections with near-zero curvature are considered less critical. The resulting scores allow for ranking connections based on their importance, enabling techniques like pruning or sparsification to reduce model complexity without significant performance degradation. This efficient computation facilitates large-scale analysis of network topology and informs strategies for model optimization and compression.

Beyond Efficiency: The Implications and Future of Pruning

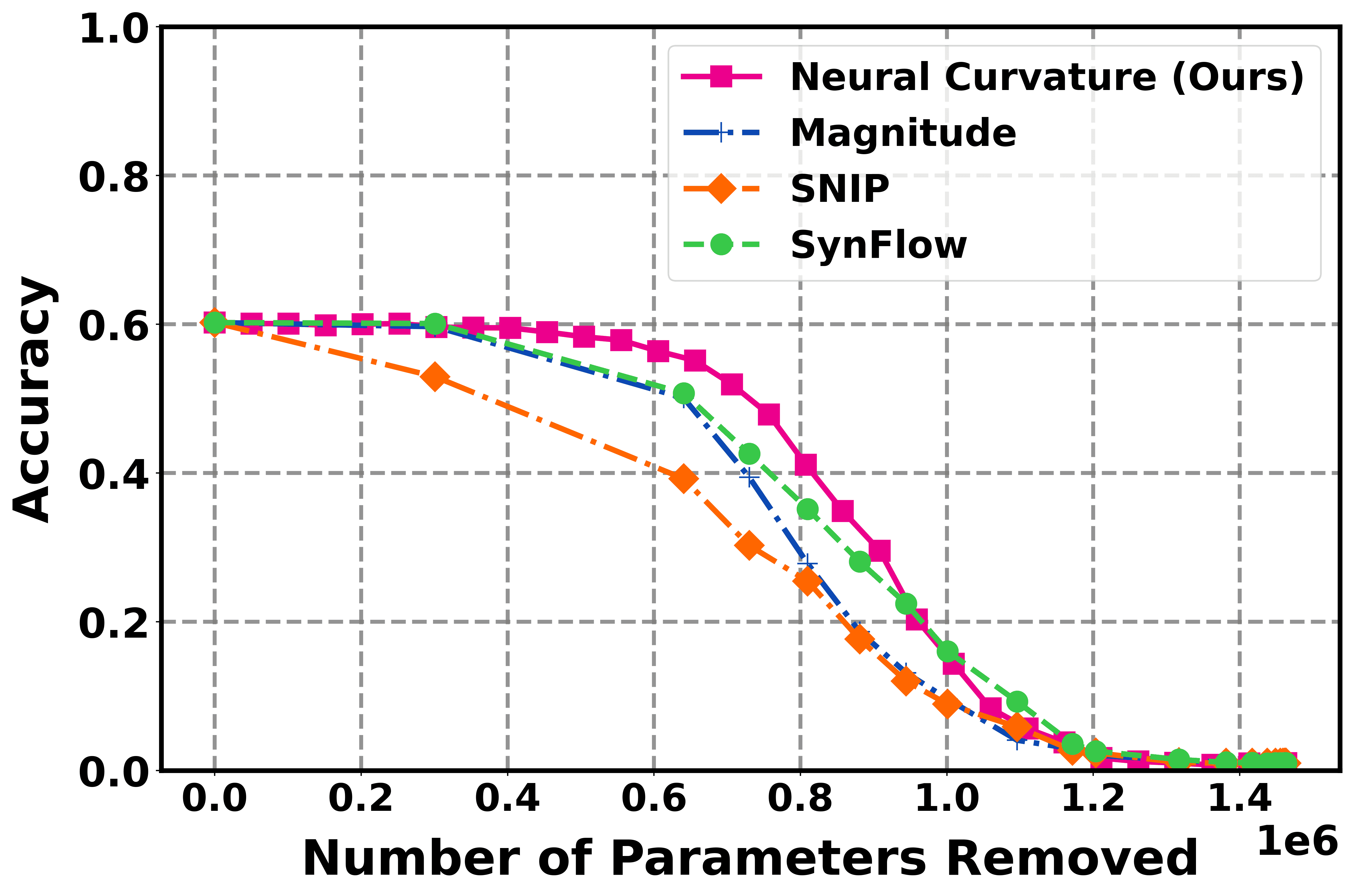

Recent investigations into neural network pruning have revealed that leveraging neural curvature-a measure of how sensitive a network’s output is to changes in its weights-offers a powerful approach to model compression. When applied to benchmark datasets including MNIST, CIFAR-10, and CIFAR-100, this curvature-based pruning technique consistently achieves substantial reductions in model size without sacrificing accuracy. In several instances, the resulting compressed models not only maintain performance comparable to their larger counterparts but actually surpass the efficiency of existing state-of-the-art pruning methods. This suggests that identifying and selectively removing connections based on their contribution to the network’s curvature provides a principled and highly effective pathway towards creating leaner, faster, and more deployable deep learning models.

The advancement of neural network pruning often relies on heuristics, but this technique distinguishes itself by offering a mathematically grounded approach to identifying and eliminating redundant connections. By analyzing the curvature of the loss landscape, the method pinpoints parameters with minimal impact on model performance, allowing for their safe removal without significant accuracy degradation. This principled approach results in models that are not only smaller and faster, requiring less computational power and memory, but also more readily deployable on resource-constrained devices. The ability to systematically reduce model complexity paves the way for broader accessibility of deep learning applications, extending their reach beyond powerful servers and into the realm of edge computing and mobile devices.

The study reveals a remarkable capacity for data efficiency in model pruning, showcasing the ability to significantly reduce network complexity using an exceptionally small calibration dataset. Unlike traditional methods requiring substantial labeled data to identify and remove redundant connections, this approach achieves comparable pruning performance with as few as ten examples per label. This limited data requirement dramatically lowers the barrier to applying pruning techniques, particularly in scenarios where labeled data is scarce or expensive to obtain. The implication is a pathway toward more adaptable and resource-conscious deep learning models, capable of being fine-tuned and optimized even with minimal supervision, and potentially deployed in data-constrained environments.

Investigations are now shifting towards extending neural curvature-based pruning to increasingly intricate deep learning models and challenging real-world applications. While initial successes have been demonstrated on standard datasets, the true potential of this technique may lie in its ability to optimize the performance of large-scale architectures used in areas like natural language processing and computer vision. Researchers anticipate that by precisely identifying and removing redundancy based on curvature, models can not only be compressed for efficient deployment on resource-constrained devices, but also potentially achieve improved generalization and robustness. This line of inquiry aims to move beyond simple model compression, exploring whether a more principled approach to network pruning, guided by curvature analysis, can unlock new levels of performance and efficiency across a broader spectrum of deep learning tasks.

The pursuit of understanding neural networks, as detailed in this analysis of information flow via differential geometry, inherently demands a willingness to challenge established assumptions. Every exploit starts with a question, not with intent. John McCarthy articulated this sentiment perfectly. The paper’s exploration of Ricci curvature as a means to pinpoint critical connections within a network isn’t simply about optimization; it’s a systematic dismantling of the ‘black box’ nature of these systems. By probing the network’s structure, researchers aren’t just improving pruning techniques – they’re reverse-engineering the very foundations of artificial intelligence, testing the limits of current methodologies to reveal underlying vulnerabilities and opportunities for advancement.

Where Do We Break It Now?

The application of differential geometry to neural network analysis, as demonstrated, offers a compelling framework – but frameworks are, by their nature, begging to be stressed. The current work primarily focuses on identifying critical connections via Ricci curvature. A logical, if somewhat disruptive, next step involves actively removing them. What happens when the network is pruned not by magnitude, but by geometric ‘flatness’? Does aggressive simplification, guided by these curvature metrics, lead to catastrophic failure, or a surprisingly robust, minimal network? The elegance of the approach demands a destructive test.

Furthermore, the assumption of a consistent geometric structure within the network requires scrutiny. Real-world data is rarely so accommodating. The method’s performance under conditions of high data dimensionality, or with networks exhibiting significant architectural heterogeneity, remains largely unexplored. To truly understand the limits of this geometric lens, one must deliberately introduce ‘noise’ – architectural irregularities, conflicting data flows – and observe the resulting distortions in the curvature landscape.

Ultimately, this isn’t about perfecting a pruning algorithm; it’s about reverse-engineering the very principles of information flow. If network geometry dictates function, then manipulating that geometry-even to the point of collapse-reveals the underlying rules. The most valuable insights may not be found in what works, but in precisely how and why it breaks.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16366.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Building 3D Worlds from Words: Is Reinforcement Learning the Key?

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Securing the Agent Ecosystem: Detecting Malicious Workflow Patterns

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Mel Gibson, 69, and Rosalind Ross, 35, Call It Quits After Nearly a Decade: “It’s Sad To End This Chapter in our Lives”

- TV Shows Where Asian Representation Felt Like Stereotype Checklists

- The Best Directors of 2025

- Games That Faced Bans in Countries Over Political Themes

- 📢 New Prestige Skin – Hedonist Liberta

- Most Famous Richards in the World

2026-01-26 15:54