Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new machine learning approach dramatically improves the detection of faint, diffuse radio emissions within massive astronomical datasets.

Combining self-supervised learning with active learning, the Protege system enhances detection rates and reduces the need for manual inspection of radio astronomy data.

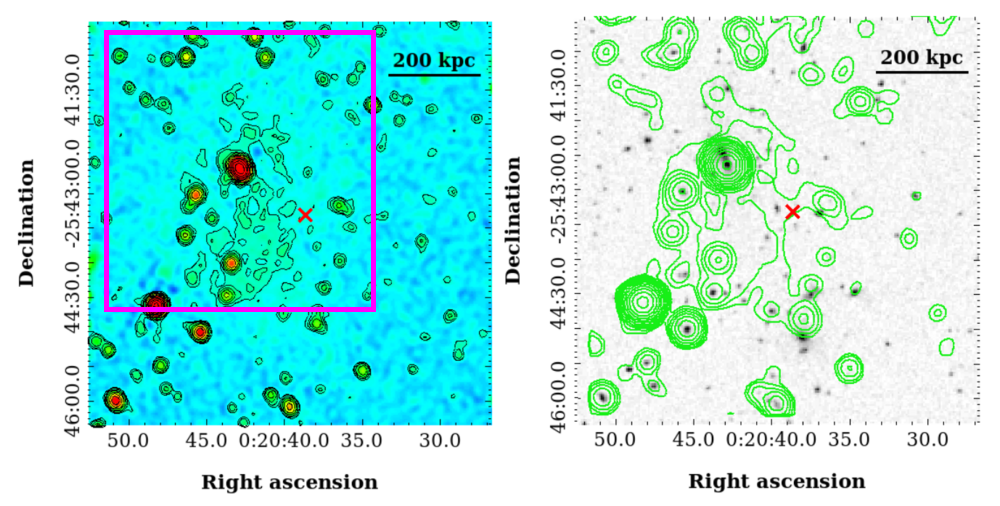

Detecting faint, extended radio emission in galaxy clusters is crucial for understanding cosmic magnetic fields and particle acceleration, yet traditional methods struggle with data volume and subtle signals. This challenge is addressed in ‘A targeted machine learning approach for detecting diffuse radio emission with Astronomaly: Protege’, which introduces a novel pipeline leveraging self-supervised learning and active learning to efficiently identify diffuse sources. The study demonstrates that combining features extracted with Bootstrap Your Own Latent and anomaly detection via the Protege framework yields remarkably high detection rates with minimal human labeling. Could this approach unlock a new era of discovery by enabling the automated identification of both known and previously unseen diffuse radio phenomena in forthcoming large-scale surveys?

The Universe Reflected: Mapping Cosmic Complexity

Galaxy clusters represent the most massive gravitationally bound structures in the universe, acting as colossal cosmic laboratories where a multitude of physical processes interplay. These aren’t static entities; instead, they are remarkably dynamic environments characterized by ongoing mergers of galaxies, the relentless flow of hot gas, and the presence of powerful magnetic fields. The sheer scale of these clusters-containing hundreds or even thousands of galaxies-amplifies these processes, creating conditions far exceeding those found in individual galaxies. Violent collisions between galaxies heat the surrounding gas to millions of degrees, while the immense gravitational forces accelerate particles to near-light speed. This constant activity makes galaxy clusters ideal for studying the fundamental laws of physics under extreme conditions, providing valuable insights into the evolution of the universe and the formation of large-scale structure.

Galaxy clusters aren’t simply collections of galaxies; they are immersed in a vast, superheated plasma known as the Intra-Cluster Medium, or ICM. This pervasive substance, constituting the majority of the cluster’s baryonic mass, reaches temperatures of tens of millions of degrees Celsius, emitting strongly in X-rays. The ICM isn’t static; it’s a dynamic environment shaped by gravitational forces, mergers of galaxies and clusters, and energetic feedback from Active Galactic Nuclei. Studying this plasma provides crucial insights into the formation and evolution of these colossal structures, revealing how matter is distributed and processed within the universe’s largest gravitational bounds. Its properties-temperature, density, and composition-serve as a powerful probe of the cluster’s history and its surrounding cosmic web.

Galaxy clusters aren’t simply collections of galaxies; their evolution is intimately tied to the behavior of the Intra-Cluster Medium (ICM). While traditionally studied for its intensely hot thermal emission, a growing body of research focuses on the ICM’s non-thermal components, particularly as revealed by Diffuse Radio Emission. This emission originates from relativistic cosmic ray electrons spiraling within magnetic fields, and its presence suggests ongoing particle acceleration processes. Understanding these non-thermal signatures is critical because they offer insights into the feedback mechanisms – such as those from active galactic nuclei and galaxy mergers – that regulate star formation and the overall energy balance within the cluster. By mapping the distribution and properties of this diffuse radio emission, astronomers can reconstruct the history of particle injection and magnetic field amplification, ultimately painting a more complete picture of how these massive structures have formed and evolved over cosmic time.

Automated Discovery: Sifting Through Cosmic Noise

Modern radio surveys, such as the Murchison Widefield Array’s Galactic Centre Survey (MGCLS), generate data volumes that exceed the capacity of traditional search methods. These surveys routinely produce datasets containing billions of radio sources, necessitating automated and efficient strategies for identifying scientifically relevant signals. Manual inspection is impractical due to the sheer scale of the data, while computationally exhaustive searches are prohibitively expensive and time-consuming. Consequently, algorithms must prioritize candidate sources based on pre-defined criteria or learned patterns to reduce the search space and enable the discovery of rare or faint astronomical phenomena within these massive datasets.

The Protege framework utilizes Active Learning to efficiently identify Diffuse Radio Emission candidates within large datasets. This iterative process begins with an initial, relatively small set of labeled data, which is used to train a model capable of predicting the probability of a given data point being a valid source. The algorithm then selects the most uncertain or informative data points for manual labeling by an expert. These newly labeled examples are incorporated back into the training set, improving the model’s accuracy and allowing it to intelligently prioritize subsequent data for review. This cycle of prediction, labeling, and model refinement continues, progressively focusing the search on regions of the data most likely to contain genuine Diffuse Radio Emission, thereby reducing the manual effort required for discovery compared to traditional methods.

Protege utilizes Gaussian Processes (GPs) as a probabilistic regression model to estimate the likelihood of a candidate radio source being genuinely interesting, effectively quantifying its potential for discovery. GPs model functions as distributions over possible functions, allowing Protege to not only predict a source’s ‘interestingness’ score but also to quantify the uncertainty associated with that prediction. This uncertainty is crucial; sources with high predicted interestingness and high uncertainty are prioritized for further investigation. The GP is trained on a set of labeled sources, learning the relationship between source features and their known classifications. The model then uses these learned relationships to assign a probability to unseen sources, effectively ranking them based on their potential to contribute to new discoveries within the MGCLS dataset. The output of the GP is a mean prediction and a variance, both contributing to the prioritization metric.

Anomaly detection functions as a supplementary layer within the automated discovery pipeline, identifying data points that deviate significantly from established patterns. This is achieved by establishing a baseline of expected characteristics within the radio survey data, and then flagging instances that fall outside predefined statistical boundaries. These flagged anomalies are not necessarily indicative of Diffuse Radio Emission, but represent unusual features requiring manual review to determine their origin and potential scientific value. The process helps to prioritize candidate sources beyond those identified through Gaussian Process predictions, potentially revealing unexpected phenomena or data artifacts that might otherwise be overlooked.

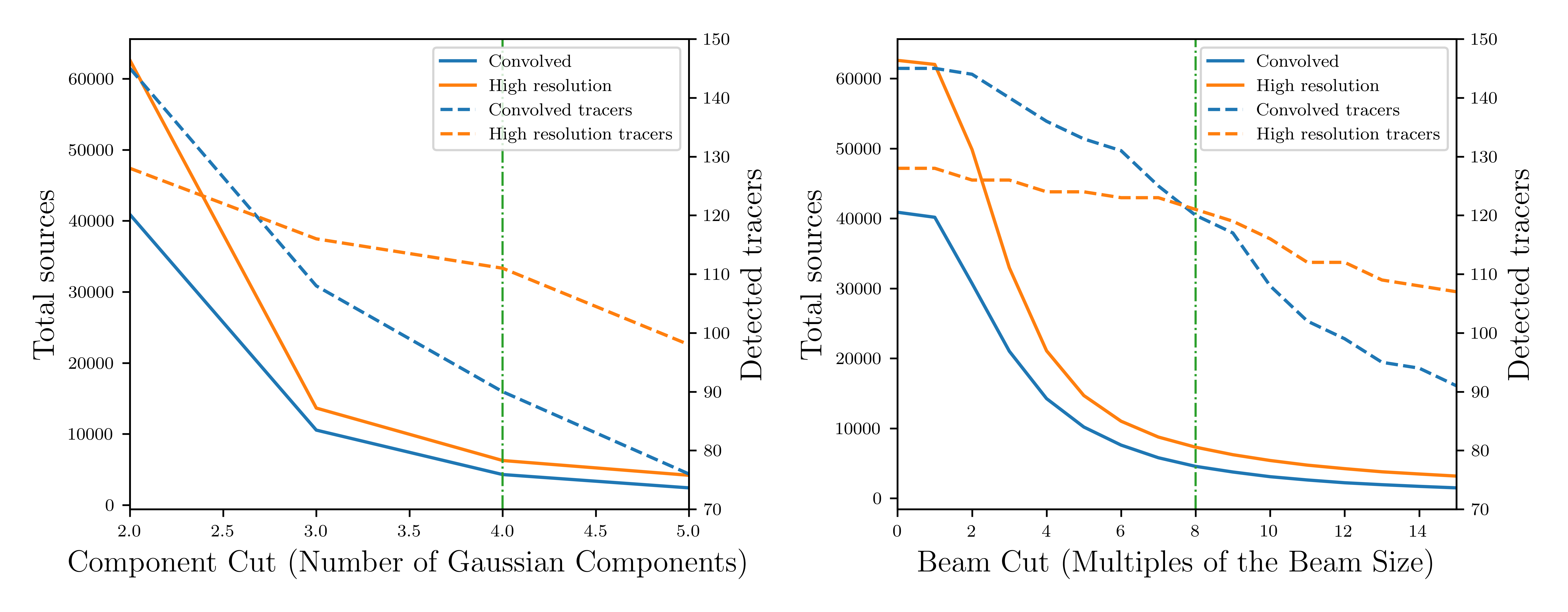

The active learning algorithm utilized a training dataset consisting of 300 labeled sources to optimize its performance in identifying potential Diffuse Radio Emission candidates. This training process was conducted over 20 iterations, with the algorithm iteratively refining its predictive capabilities based on feedback from each iteration. During each cycle, the algorithm assessed the ‘interestingness’ of unlabeled data, selected the most informative sources for labeling, and incorporated these new labels to improve its model. This iterative approach allowed the algorithm to efficiently learn the characteristics of desired sources, minimizing the need for extensive manual labeling and maximizing the discovery of relevant candidates within large datasets like those produced by the MGCLS survey.

Self-Supervised Learning: Unveiling Hidden Structure

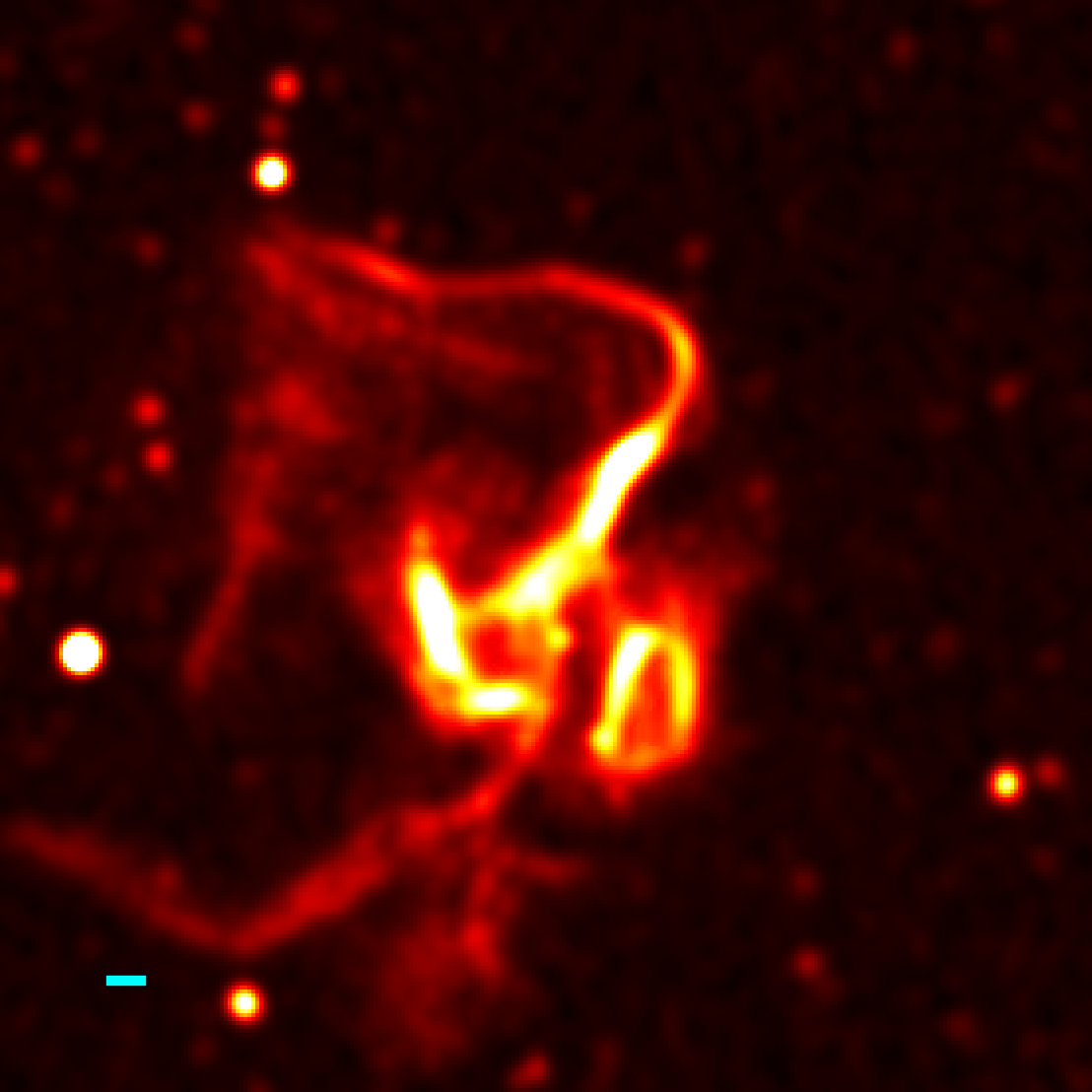

The extraction of meaningful features from radio images is intrinsically difficult due to inherent characteristics of the data. Diffuse Radio Emission, which includes structures like halos and relics, often exhibits a low signal-to-noise ratio, meaning the signal representing the astronomical source is weak relative to the background noise. Furthermore, the complexity of these diffuse structures-characterized by faint, irregular morphologies and gradients-necessitates sophisticated analysis techniques to differentiate genuine emission from noise artifacts. These combined factors limit the effectiveness of traditional image processing and feature extraction methods, demanding innovative approaches to accurately identify and characterize diffuse radio sources.

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) addresses the limitations of supervised machine learning by enabling models to learn useful representations from data without requiring explicit, manually assigned labels. This is achieved by formulating pretext tasks that leverage the inherent structure within the unlabeled data itself. Rather than relying on human annotation, SSL algorithms create labels automatically based on relationships within the data – for example, predicting a missing portion of an image or the relative position of image patches. By learning to solve these pretext tasks, the model develops a robust understanding of the underlying data distribution, resulting in feature representations applicable to downstream tasks. This approach significantly reduces the need for costly and time-consuming manual labeling, particularly beneficial when dealing with large datasets, such as radio images, where obtaining labeled examples is challenging.

The BYOL (Bootstrap Your Own Latent) algorithm is employed as the self-supervised learning method due to its demonstrated ability to learn effective visual representations without relying on labeled data. BYOL operates by training a network to predict its own representations from different augmented views of the input radio images. This is achieved through a predictor network and a target network, where the target network’s weights are updated as an exponential moving average of the predictor network’s weights. This architecture encourages the network to learn features that are invariant to the applied data augmentations, resulting in robust feature extraction from the inherently noisy radio data and ultimately improving the identification of diffuse emission features.

The features extracted via self-supervised learning are instrumental in differentiating between the three primary types of diffuse radio emission observed in galaxy clusters: Radio Halos, Radio Relics, and Radio Mini-Halos. Radio Halos are extended, centrally-peaked emissions, while Radio Relics exhibit irregular, filamentary structures typically found at cluster peripheries, often associated with merger shocks. Radio Mini-Halos are centrally concentrated, smaller-scale emissions generally linked to active galactic nuclei (AGN) within the cluster. The learned feature representations effectively capture the morphological and spectral characteristics unique to each emission type, enabling automated identification and characterization which bypasses the need for manual, time-intensive analysis. This differentiation is crucial for understanding the physical processes-such as cluster mergers and AGN activity-that drive the generation and evolution of diffuse radio emission.

The feature extraction method achieved a recovery rate of 55 out of 121 known radio emission tracers when considering only the top 100 ranked sources. This indicates a high degree of efficiency in identifying genuine signals amidst background noise and false positives. The metric demonstrates the algorithm’s ability to prioritize and accurately classify diffuse emission sources, effectively reducing the need for exhaustive manual inspection of the entire dataset. This performance suggests that the learned features are highly discriminative and capture the essential characteristics of the target tracers.

The self-supervised learning approach demonstrated high efficiency in identifying known radio emission tracers. Initial analysis of 62,587 sources required inspection of only 250 to recover 61 out of a total 121 known tracers. This represents a recovery rate of approximately 50.4% from a very small fraction – 0.4% – of the total source population, indicating the learned features effectively prioritize and identify relevant diffuse emission even with limited manual review.

Visualizing the Invisible: Mapping Cosmic Patterns

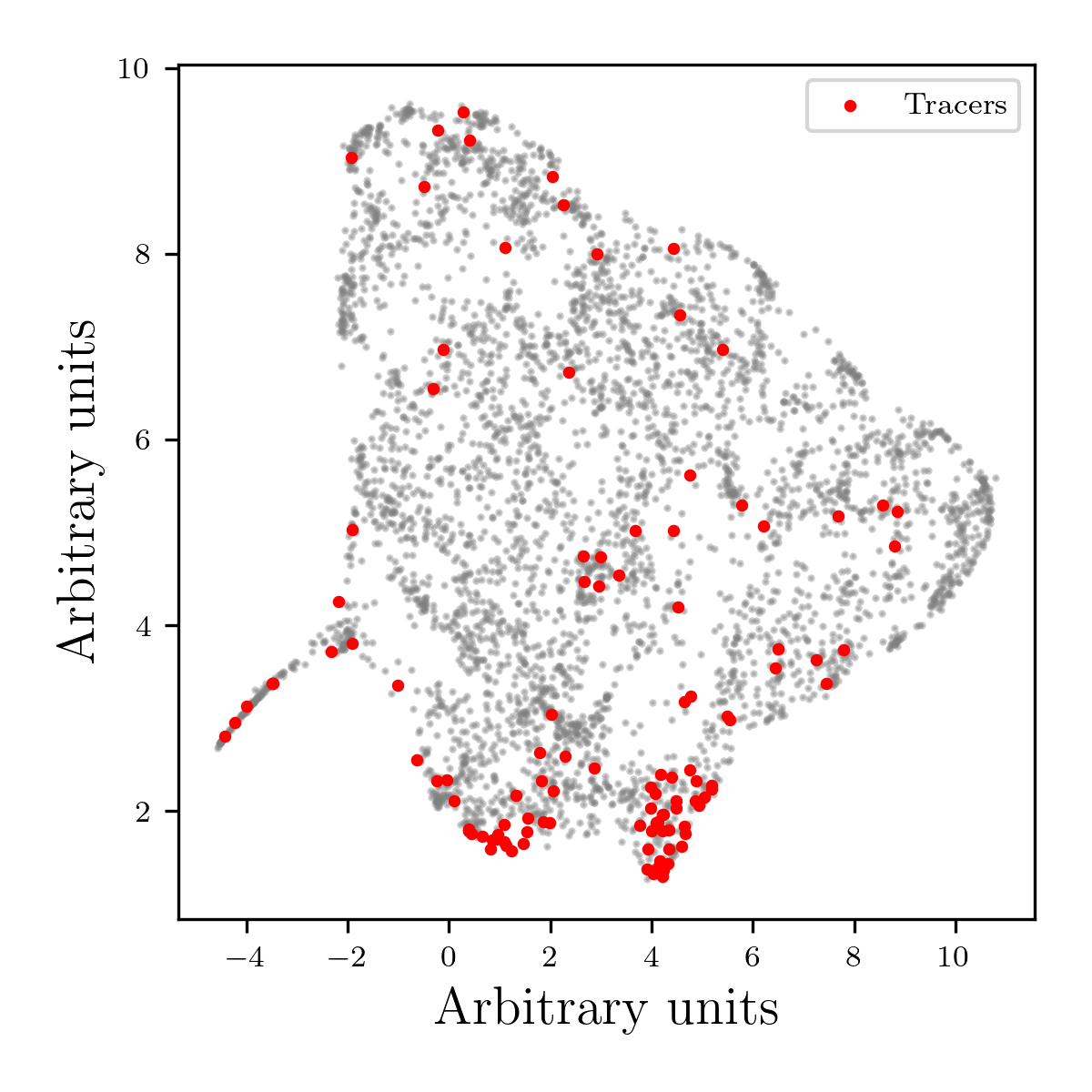

Radio images, when processed to extract meaningful features for analysis, often result in datasets with a very large number of dimensions – a so-called ‘high-dimensional feature space’. While these spaces capture nuanced information about the radio emission, directly interpreting them proves remarkably challenging for researchers. The sheer complexity makes it impossible for the human mind to intuitively grasp relationships or identify patterns within the data. Each dimension represents a specific characteristic of the radio signal, and the combination of hundreds or even thousands of these characteristics creates a landscape too intricate to navigate visually or conceptually. Consequently, techniques are needed to reduce this complexity while preserving the essential information, enabling scientists to discern underlying structures and gain a deeper understanding of the phenomena being observed.

Analyzing data from radio astronomy often involves navigating extraordinarily high-dimensional feature spaces – datasets with so many variables that direct interpretation becomes impossible. To overcome this challenge, researchers employ dimensionality reduction techniques, with UMAP – Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection – proving particularly effective. UMAP skillfully compresses these complex datasets into a lower-dimensional space, typically two or three dimensions, while preserving the essential relationships between data points. This allows for visual exploration of the data, transforming abstract numerical information into scatter plots where patterns and clusters become readily apparent. By revealing the inherent structure within the data, UMAP facilitates the identification of groupings and correlations that would otherwise remain hidden, ultimately enabling a deeper understanding of the underlying astrophysical phenomena.

By applying dimensionality reduction techniques to complex radio data, researchers can visually map the relationships between different instances of Diffuse Radio Emission. These visualizations aren’t merely aesthetic; they reveal groupings of emission patterns that suggest shared physical origins or evolutionary stages. Previously obscured connections between various emission types-such as relics, halos, and filaments-become apparent, allowing scientists to move beyond simple classification and begin to understand the underlying processes driving their formation and interaction within galaxy clusters. This capability facilitates a more nuanced understanding of the energetic phenomena at play in these vast cosmic structures, potentially linking emission characteristics to cluster merger history, magnetic field strength, and the distribution of relativistic particles.

Understanding the subtle interplay of physical processes within and around galaxy clusters – colossal structures containing thousands of galaxies – requires detailed analysis of diffuse radio emission. Recent investigations reveal that mapping and categorizing these emissions isn’t merely an exercise in astronomical cataloging; it’s a pathway to unraveling the complex mechanisms governing cluster evolution. By identifying patterns in radio signals, researchers are gaining insight into phenomena like mergers of galaxy clusters, the acceleration of cosmic ray particles within the intracluster medium, and the feedback effects of active galactic nuclei. This detailed picture allows for more accurate modeling of cluster formation, growth, and the distribution of matter throughout the universe, ultimately refining cosmological understanding of large-scale structure.

A comprehensive analysis of the highest-ranked sources revealed an unexpectedly high prevalence of diffuse radio emission; fully 99 out of the top 100 sources displayed this characteristic. This suggests diffuse emission is not a rare phenomenon, but rather a common feature of the most prominent radio-emitting objects. Within this group, 55 sources were definitively identified as tracers of emission within galaxy clusters, while the remaining 44 exhibited other forms of diffuse radio emission, hinting at a diverse range of underlying physical processes and emission mechanisms at play. This strong correlation between ranking and the presence of diffuse emission underscores its importance as a key indicator of energetic activity and complex environments in these astronomical sources.

The pursuit of identifying diffuse radio emission, as detailed in this work, echoes a humbling truth about knowledge itself. The application of machine learning, specifically the combination of self-supervised and active learning techniques, isn’t about conquering the cosmos, but rather about refining the questions asked of it. As Sergey Sobolev once noted, “The universe doesn’t reveal its secrets to those who demand answers, but to those who are willing to listen.” This study, by lessening the burden of human inspection while simultaneously improving detection rates, demonstrates a willingness to listen-to allow the data to guide the inquiry, acknowledging that even the most sophisticated theories, like those attempting to model diffuse emission, remain provisional. The cosmos generously shows its secrets to those willing to accept that not everything is explainable; black holes are nature’s commentary on our hubris.

Beyond the Horizon

The successful application of self-supervised and active learning techniques, as demonstrated by Astronomaly’s Protege, offers a temporary reprieve from the ever-increasing volume of astronomical data. However, one should not mistake algorithmic efficiency for genuine understanding. The identification of diffuse radio emission, while improved, remains contingent upon the biases inherent in both the training data and the chosen algorithms. Multispectral observations enable calibration of accretion and jet models, yet these models are, ultimately, simplifications – convenient fictions imposed upon a reality that may resist such neat categorization.

Future work must address the limitations of current machine learning approaches. A critical step involves developing methods for quantifying uncertainty and identifying instances where algorithmic confidence does not align with physical plausibility. Comparison of theoretical predictions with EHT data demonstrates both limitations and achievements of current simulations. The pursuit of ever-more-sophisticated algorithms risks obscuring the fundamental question: are these tools truly revealing the universe, or merely reflecting the limitations of the observer’s capacity for comprehension?

The challenge, then, is not simply to automate detection, but to cultivate a methodology that acknowledges the provisional nature of all knowledge. Each identified emission, each refined model, is a fleeting glimpse beyond the event horizon – a reminder that the most profound insights may lie in recognizing the boundaries of what can be known.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.15930.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Building 3D Worlds from Words: Is Reinforcement Learning the Key?

- The Best Directors of 2025

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- 20 Best TV Shows Featuring All-White Casts You Should See

- Mel Gibson, 69, and Rosalind Ross, 35, Call It Quits After Nearly a Decade: “It’s Sad To End This Chapter in our Lives”

- Umamusume: Gold Ship build guide

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 39th Developer Notes: 2.5th Anniversary Update

- TV Shows Where Asian Representation Felt Like Stereotype Checklists

- The Most Famous Foreign Actresses of All Time

2026-02-20 03:27