Video games commonly use voice-overs to tell the story or help players learn how to play. Some games go further, using narrators who playfully point out that it is a game. These voices might respond to what you do or joke about the strange things that happen in video games. This creates a special connection between the game creators and the person playing.

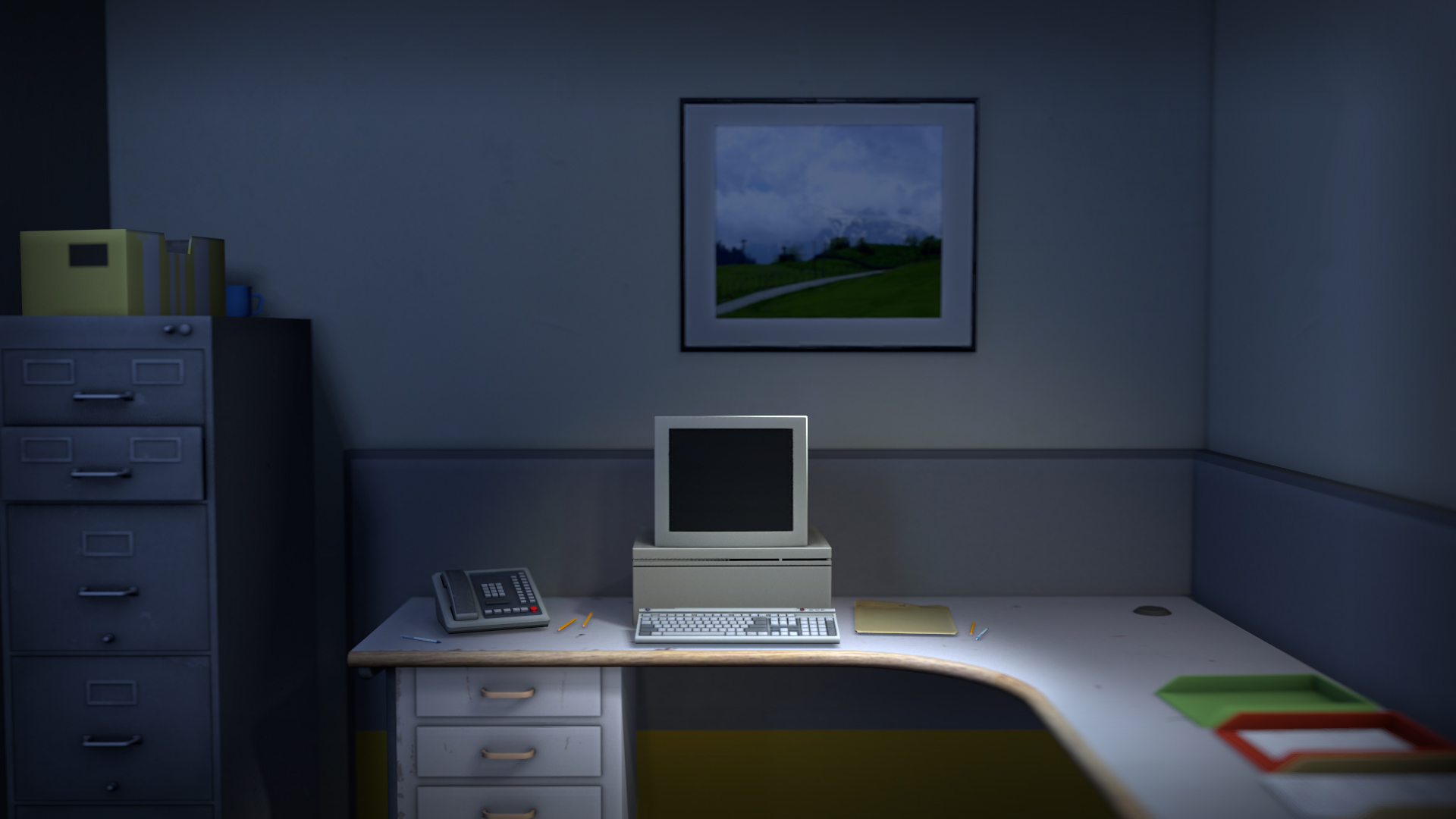

‘The Stanley Parable’ (2013)

The game features a Narrator who tries to lead the player through a typical office setting, but gets visibly confused and annoyed whenever the player ignores his directions. This creates a power struggle between the Narrator, who’s telling the story, and the player, who’s in control. The Narrator’s reactions constantly make you think about how much real choice you actually have in a game with a set path.

‘Bastion’ (2011)

Rucks narrates the game with a rough, engaging voice that responds directly to what the player does. He offers immediate feedback on weapon choices and mistakes, making the story feel natural and connected to the gameplay. This approach creates a sense that the player isn’t just playing a legend, but living one that unfolds as they go.

‘Call of Juarez: Gunslinger’ (2013)

Silas Greaves loves to tell wild stories about his bounty hunting days, but the people listening in the saloon aren’t so sure he’s telling the truth. As he speaks, the world around the player changes – hallways appear and disappear, and enemies move – reflecting Silas’s shifting memories and exaggerations. The game uses these instant changes to explain why things keep resetting and to make sense of the unpredictable enemy placements, framing it all as part of a larger-than-life story.

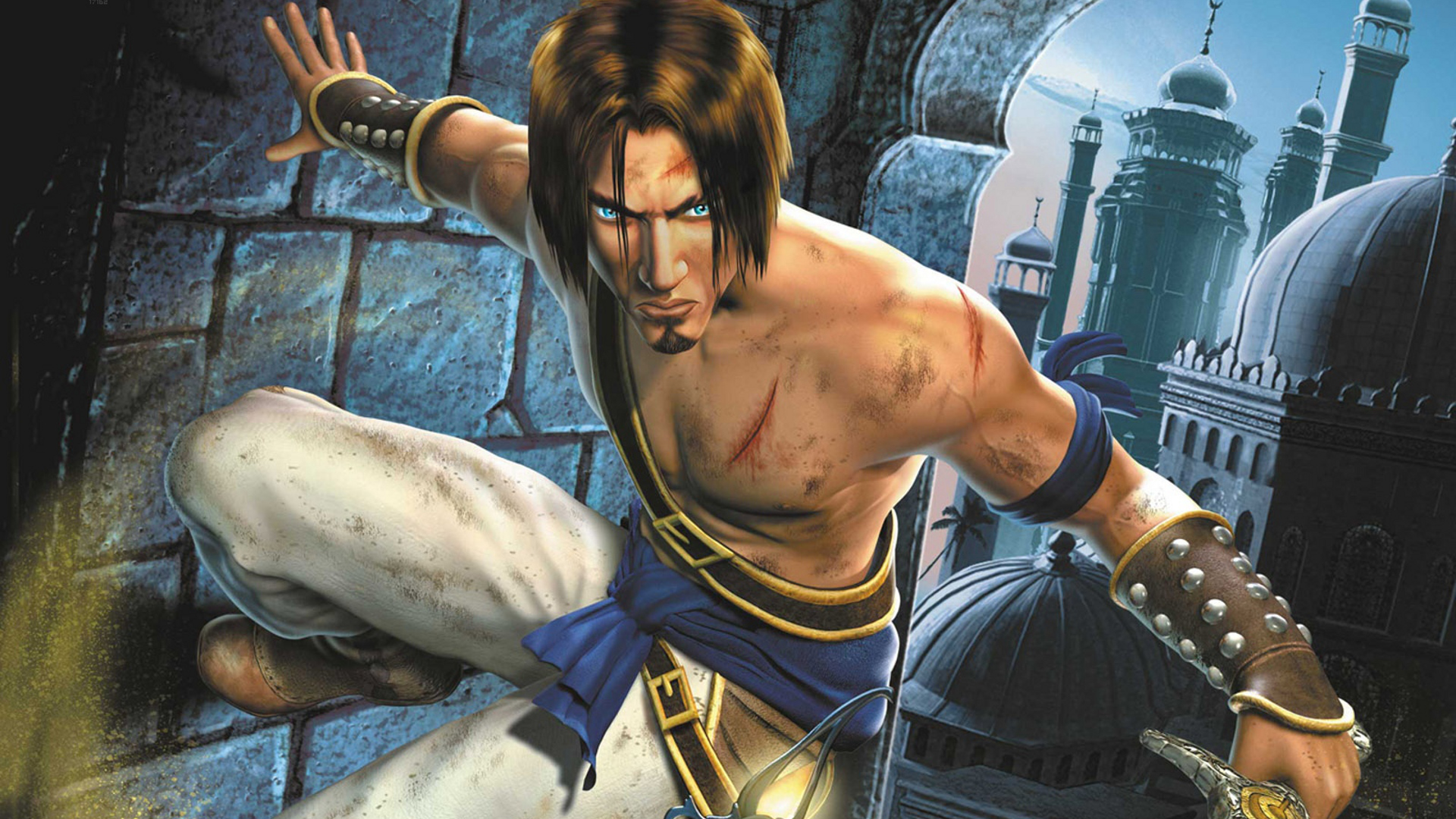

‘Prince of Persia: The Sands of Time’ (2003)

The game is presented as a story the Prince is telling to Princess Farah, looking back on events. Interestingly, the Prince directly addresses the player – breaking the fourth wall – especially when the player’s character dies, claiming things didn’t happen as seen. The game lets you rewind time to fix mistakes and continue the story as it ‘really’ happened. This is a smart way to explain why the player can keep trying after failing – it’s built into the story itself.

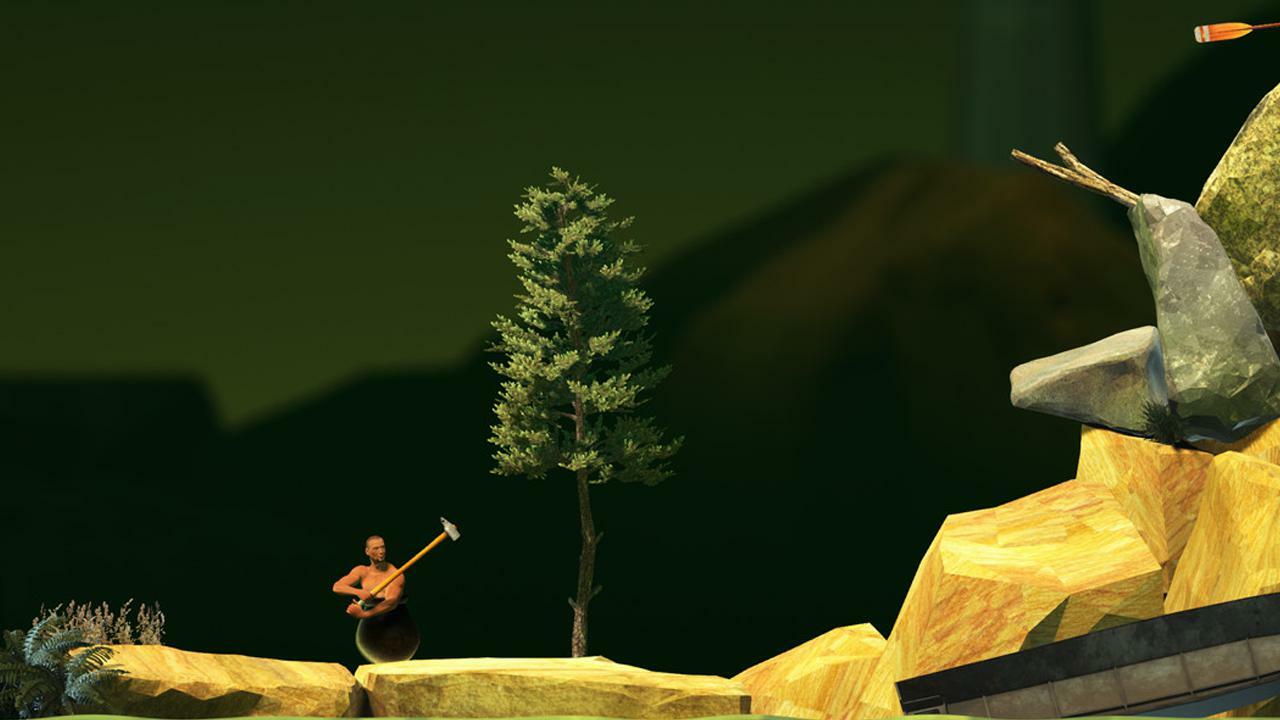

‘Getting Over It with Bennett Foddy’ (2017)

In the game, Bennett Foddy talks to you while you try to climb a bizarre, dreamlike mountain. He reflects on why things are frustrating and what it means to fail, all as you battle the purposefully tricky controls. His words are meant to both encourage and playfully tease you when you fall, creating a unique connection – almost like a conversation – between the game’s creator and the person playing it.

‘The Beginner’s Guide’ (2015)

Davey Wreden guides players through early, incomplete versions of games made by a developer known only as Coda. He discusses why certain design choices were made and encourages players to find their own meaning in the games. As the game progresses, Wreden’s commentary becomes more personal, revealing his own doubts and anxieties about his friend’s work. This creates a unique experience that feels like both a behind-the-scenes look and a fictional story about seeking approval as a creator.

‘Darkest Dungeon’ (2016)

The Ancestor offers a bleak outlook on the heroes’ struggles, commenting on their failures and the harsh reality of death as the player deals with stress. His voice constantly underscores the game’s hopeless atmosphere, even when the team wins. The storytelling presents the game as a never-ending, tragic loop that the player is destined to repeat.

‘Thomas Was Alone’ (2012)

Danny Wallace provides the voice for a narrator who imagines that basic shapes have rich inner lives. As players move these shapes through puzzles, the narration reveals their supposed feelings and thoughts. The story suggests these shapes are becoming aware, thanks to the player’s actions. This creates a surprisingly strong emotional bond with these simple, abstract characters, all through what you hear.

‘The Bard’s Tale’ (2004)

This funny RPG features a Narrator who constantly teases the main character, a Bard. The Narrator makes fun of the player for doing things that are common in video games or for struggling with easy tasks. The Bard usually responds, leading to a playful back-and-forth that pokes fun at typical RPG clichés. This creates a lighthearted and amusing dynamic throughout the game.

‘ICEY’ (2016)

The game features a narrator who tries to lead the main character, a cyborg, through a typical action storyline, but players are free to ignore his instructions. As the player deviates from the intended path – exploring incomplete sections or disregarding on-screen cues – the narrator grows frustrated and starts to abandon his role. This conflict transforms the game from a simple side-scroller into a commentary on how games are made. The story isn’t revealed through following directions, but by actively disobeying them.

‘LittleBigPlanet’ (2008)

Stephen Fry’s narration feels like a friendly guide, helping players explore the game’s creative tools. He doesn’t act like a character within the game, but more like a fellow creator, inviting you into a world of imagination. The tutorials aren’t stiff lessons; they’re relaxed and conversational, focusing on enjoying the experience and encouraging you to experiment and play.

‘Portal 2’ (2011)

Throughout the game, GLaDOS offers backhanded compliments and points out how obviously fake the tests are, often belittling the player’s intelligence and the point of even trying. Adding to the unsettling atmosphere, Cave Johnson provides pre-recorded messages that strangely seem to know what the player will do next. This constant commentary reinforces the feeling that the player isn’t truly in control, but is instead being watched and analyzed.

‘Stories: The Path of Destinies’ (2016)

The game features a narrator who reads a story that changes as you play, shaped by the choices you make. He provides lively descriptions of battles and exploration, hinting at what might happen next. The narrator also remembers your repeated attempts to unlock the game’s true ending, playfully acknowledging the time loop without ruining the immersive experience.

‘Disco Elysium’ (2019)

The main character’s thoughts are presented through different inner voices that struggle for dominance, creating a dynamic internal dialogue. These voices often react to the player’s decisions, challenging the reasoning or ethics behind their choices. Representing the character’s instincts, the ‘Reptilian Brain’ and ‘Limbic System’ also speak directly to the player. This creates a feeling that the character’s stats are actually a group of personalities, all judging your actions.

‘Immortals Fenyx Rising’ (2020)

The game features Zeus and Prometheus as narrators who both tell the story, often disagreeing with each other. Zeus frequently speaks directly to the player, commenting on how the game is going or questioning what’s happening. Their playful arguments actually affect the game itself, instantly creating monsters or changing the time. Together, they’re like both an audience watching the action and a director controlling it.

Tell us which game narrator you think broke the fourth wall most effectively in the comments.

Read More

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Top 15 Insanely Popular Android Games

- Did Alan Cumming Reveal Comic-Accurate Costume for AVENGERS: DOOMSDAY?

- 4 Reasons to Buy Interactive Brokers Stock Like There’s No Tomorrow

- EUR UAH PREDICTION

- DOT PREDICTION. DOT cryptocurrency

- Silver Rate Forecast

- ELESTRALS AWAKENED Blends Mythology and POKÉMON (Exclusive Look)

- New ‘Donkey Kong’ Movie Reportedly in the Works with Possible Release Date

- Core Scientific’s Merger Meltdown: A Gogolian Tale

2025-12-11 06:15