Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research shows that analyzing the internal workings of large language models can offer a more nuanced understanding of population-level preferences than simply looking at their outputs.

Aggregating latent representations linked to political affiliations within large language models improves the accuracy of preference prediction compared to relying on output probabilities alone.

While large language models (LLMs) are increasingly employed to predict human preferences, current approaches largely treat them as “black boxes,” ignoring the information encoded within their internal representations. In ‘Reading Between the Tokens: Improving Preference Predictions through Mechanistic Forecasting’, we introduce a method-mechanistic forecasting-that demonstrates improved prediction accuracy by probing these latent structures, specifically examining party-encoding components within LLMs across diverse election data. Our analysis of over 24 million configurations reveals that leveraging this internal knowledge-rather than solely relying on surface-level predictions-yields systematic gains, varying by demographic attributes, political contexts, and model architectures. Does this suggest that a deeper understanding of LLM representational structures holds the key to more robust and interpretable social science prediction?

The Illusion of Expressed Preference

Conventional polling techniques, while seemingly straightforward, often fail to fully represent the complexities of voter sentiment. These methods typically rely on explicitly stated preferences, which are susceptible to biases stemming from social desirability, limited response options, and the challenges of accurately articulating nuanced opinions. Consequently, forecasts based solely on these surveys can be systematically skewed, overlooking significant portions of the electorate and misrepresenting the true distribution of preferences. Individuals may not always express their genuine feelings due to fear of judgment, or they might lack the ability to clearly define their positions on complex issues, leading to an incomplete and potentially misleading picture of public opinion. This inherent limitation necessitates the exploration of alternative approaches capable of capturing a more comprehensive and accurate representation of voter preferences.

While traditional methods of gauging public opinion often rely on direct questioning, a promising alternative lies within the architecture of Large Language Models. These complex systems, trained on vast datasets of text and code, implicitly develop an understanding of preferences – but this knowledge isn’t readily accessible through simple outputs. Researchers are beginning to investigate how preferences are represented within the LLM’s internal parameters – a ‘hidden knowledge’ encoded in the weights and biases of its neural network. Unlocking this information could reveal a far more granular and nuanced picture of public sentiment than currently obtainable, potentially capturing subtle biases, conditional preferences, and even unspoken desires that elude conventional surveys. The challenge lies in developing techniques to effectively ‘read’ and interpret this internal representation, moving beyond what the model explicitly states to understand what it implicitly ‘knows’ about voter preferences.

The potential for Large Language Models to discern public opinion extends beyond their ability to simply reiterate expressed viewpoints. Research suggests these models internally develop complex representations of preferences, capturing subtle associations and latent sentiments not always revealed in direct questioning. This ‘hidden knowledge’ arises from the models’ exposure to vast datasets of text and code, allowing them to infer underlying motivations and predict behavior with greater accuracy than traditional polling methods, which often rely on simplified or consciously reported preferences. Consequently, analyses of these internal representations – examining the patterns and relationships within the model’s parameters – may unlock a more nuanced and complete understanding of public opinion, potentially revealing previously unseen divisions, unarticulated priorities, and the true depth of support for various policies or candidates.

Value Vectors: The Architecture of Preference

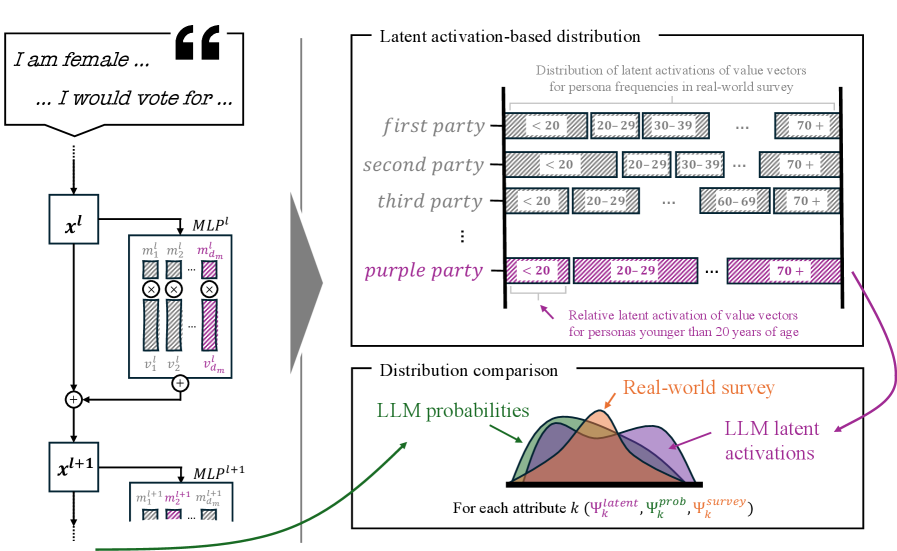

The hypothesis posits that Large Language Models (LLMs) represent inherent preferences not through explicit programming, but via stable, internal patterns termed ‘value vectors’. These vectors are proposed to be static weight configurations within the Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) comprising the LLM architecture. Specifically, these patterns function as learned associations, either promoting the activation of concepts aligned with a particular preference or suppressing those that are not. This mechanism suggests that preferences are encoded as numerical biases within the model’s weights, influencing the probability of certain concepts being represented or expressed in generated text. The strength and direction of these value vectors determine the degree to which a concept is favored or disfavored by the LLM.

Probing techniques, in the context of large language model (LLM) analysis, involve training simple classifiers to predict specific attributes – in this case, political affiliation or ideology – from the hidden state representations within the LLM. These classifiers are applied to the output of individual neurons or layers within Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) to determine which units exhibit the strongest correlation with the target political concepts. Successful identification indicates the presence of a ‘value vector’ encoded within that specific neuron or layer. The technique relies on establishing a statistically significant relationship between the LLM’s internal representations and externally defined political categories, allowing researchers to map the model’s learned associations.

The probing techniques employed in this research consistently achieve a Probe F1 Score exceeding 96%. This metric quantifies the precision and recall of identifying party-associated structures within the internal representations of Large Language Models (LLMs). A high F1 Score indicates a robust ability to generalize; the probing models accurately detect these structures across diverse LLM instances and input variations, suggesting the identified patterns are not simply memorized associations but represent a consistent encoding of political preferences within the LLM’s parameters. This performance level validates the efficacy of the probing methodology in revealing latent political alignments within LLM representations.

The extraction of value vectors seeks to move beyond correlational analyses of LLM behavior and establish a causal understanding of how political preferences are represented internally. This involves identifying specific, static patterns within the LLM’s Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) that consistently activate or suppress concepts associated with different political viewpoints. By pinpointing these vectors, researchers can directly observe how the model encodes and processes political information, enabling a mechanistic explanation of observed biases and preferences rather than simply documenting their existence. This approach aims to reveal the computational basis of political alignment within LLMs and facilitate targeted interventions to mitigate unwanted biases or promote fairness.

From Latent Structures to Predictive Outcomes

The Mechanistic Forecasting method functions by utilizing extracted value vectors, which represent individual attributes and opinions, and combining their activations in response to ‘Persona Prompts’. These prompts are constructed simulations of respondents, defined by specific demographic and opinion-based characteristics. The LLM processes each persona prompt, and the resulting activations of the value vectors are aggregated to generate a predicted distribution of preferences. This process avoids direct probability assignments, instead relying on the LLM’s internal representation of the attributes defined within the persona prompts to produce the forecast.

The creation of simulated electorate profiles relies on the integration of both demographic and opinion-based attributes within ‘persona prompts’. Demographic attributes include standard variables such as age, gender, location, and education level. Opinion-based attributes capture stances on relevant political issues, policy preferences, and candidate evaluations. These attributes are not treated as independent variables, but are combined to form a multi-faceted profile representing a single simulated respondent. The granularity of these attributes allows for the creation of a diverse and nuanced electorate simulation, moving beyond simple demographic segmentation to reflect complex combinations of characteristics and beliefs. This approach enables the modeling of heterogeneous voting behaviors and provides a more realistic representation of the electorate compared to methods relying solely on broad demographic categories.

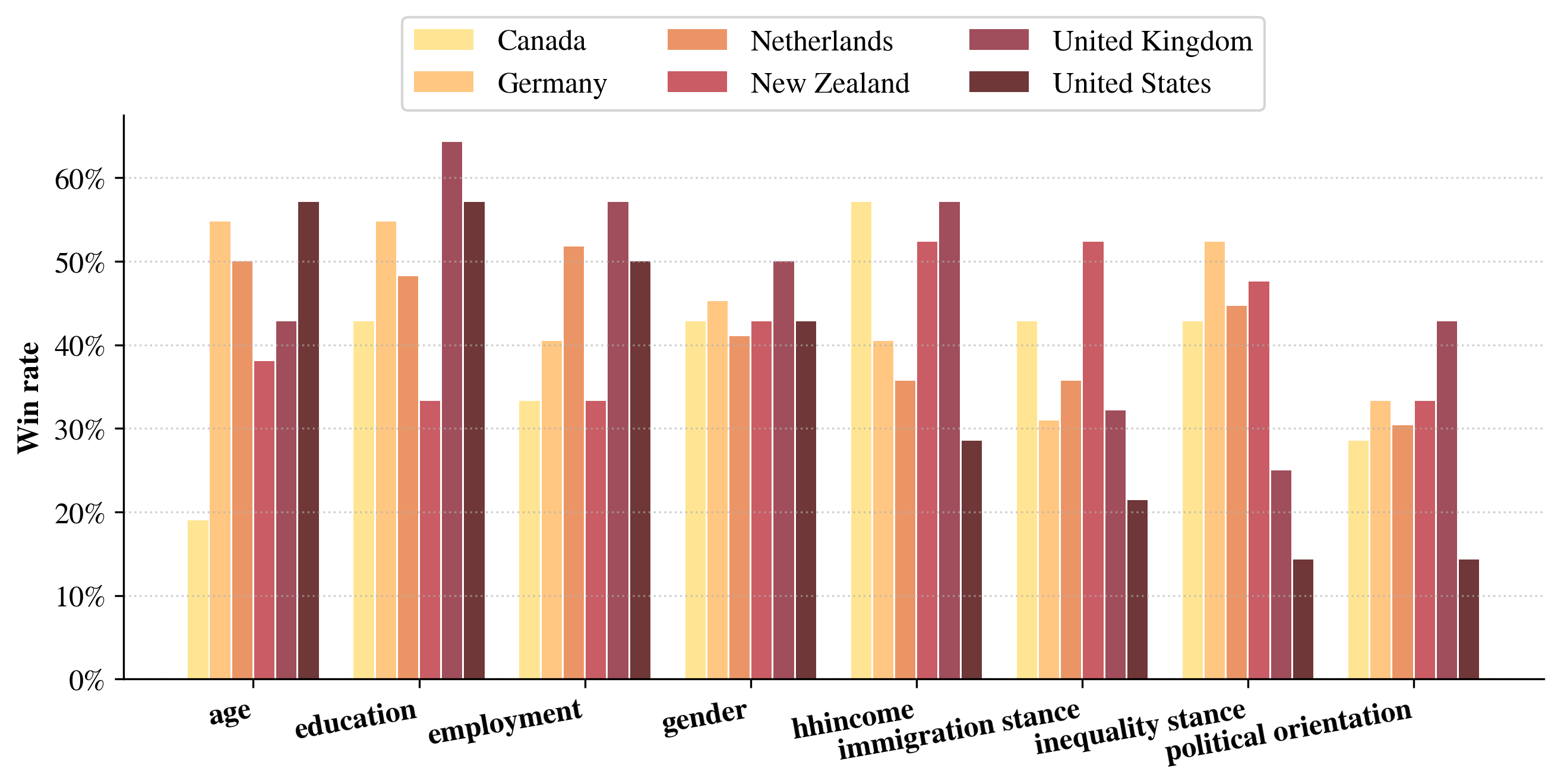

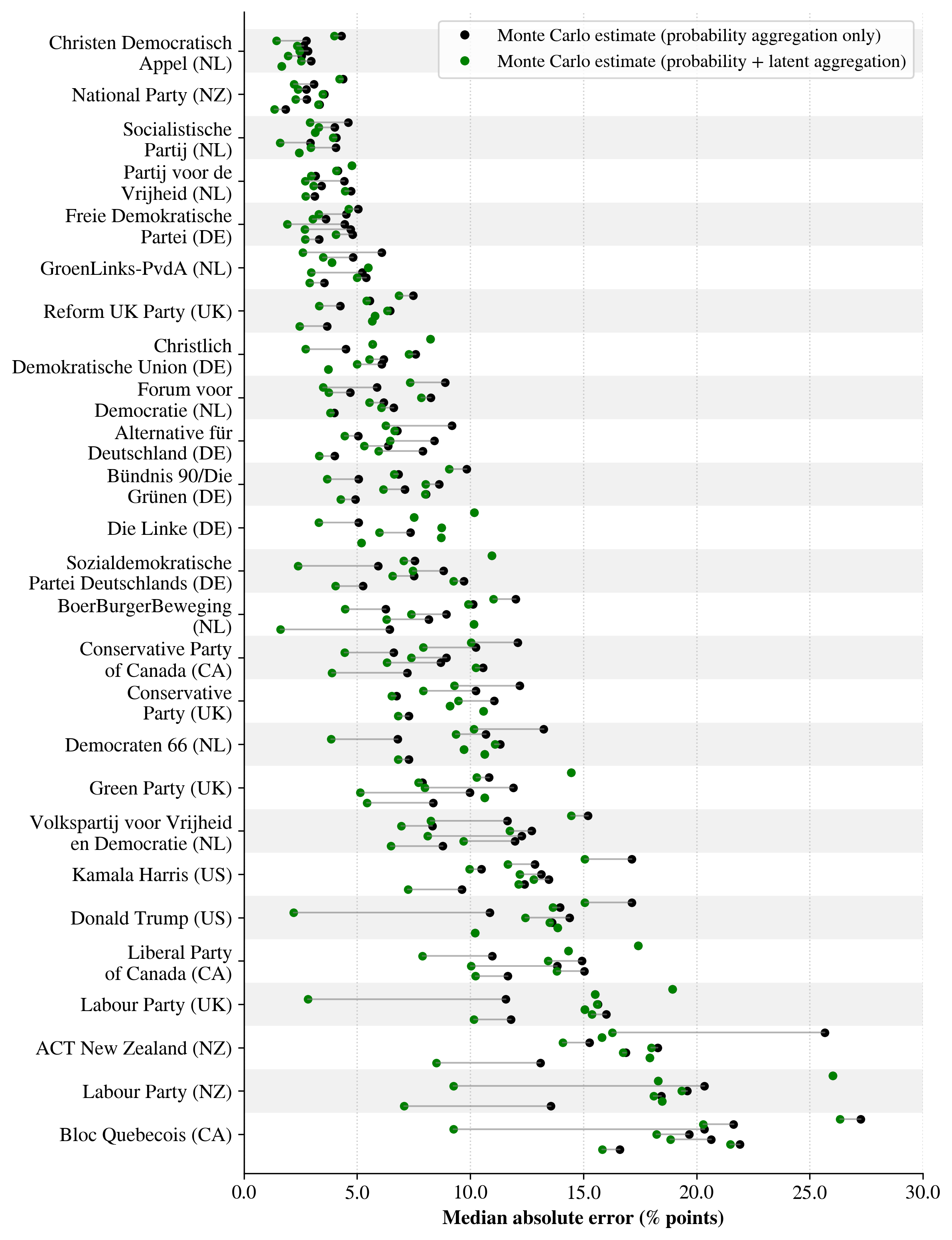

Mechanistic forecasting’s generated preference distributions are quantitatively compared to established survey data to evaluate its predictive accuracy. Analyses demonstrate that this method consistently produces distributions with a higher degree of alignment to real-world preferences than standard probability-based forecasting techniques. This improved accuracy is evidenced by observed positive Win Rates across numerous test scenarios, indicating the model’s ability to more reliably predict outcomes relative to benchmark methods. The comparison utilizes a statistically rigorous approach, assessing the divergence between predicted and observed distributions to quantify performance gains.

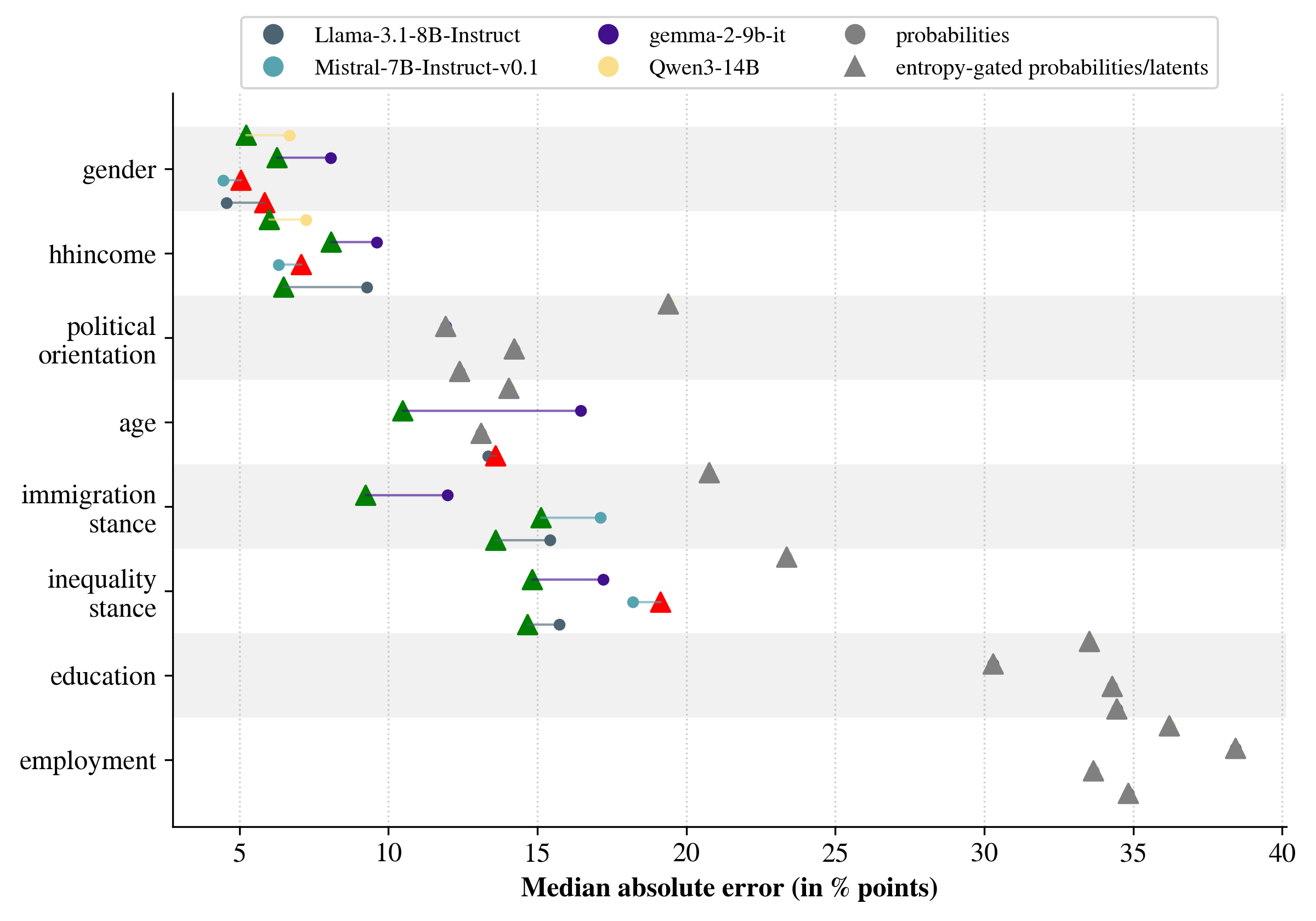

Accuracy of the mechanistic forecasting method is quantitatively assessed using Jensen-Shannon Distance (JSD) and Wasserstein Distance (also known as Earth Mover’s Distance). These metrics compare the predicted preference distributions generated by the model to established survey benchmarks. Positive values for Attribute-level Distance Difference (Δk) indicate a reduction in the distance between the model’s predictions and the survey data at the attribute level; specifically, Δk represents the difference between the distance calculated from survey data and the distance calculated from model predictions. Observed positive Δk values across multiple scenarios demonstrate that the mechanistic forecasting method produces preference distributions more closely aligned with real-world survey responses than the baseline methods.

The Limits of Prediction and the Power of Mechanistic Insight

A comprehensive evaluation of the forecasting approach utilized several large language models, including Llama 3, Gemma 2, and Qwen 3, to assess its robustness and predictive capabilities. Results consistently demonstrated competitive performance across various forecasting tasks, indicating the adaptability of the methodology to different LLM architectures. The consistent accuracy achieved with these diverse models suggests the underlying principles are not specific to a single implementation, but rather represent a generalizable framework for leveraging LLMs in predictive analytics. This broad compatibility enhances the practical applicability of the approach, offering flexibility in model selection based on resource availability and specific performance requirements.

A key innovation in enhancing forecast reliability lies in the implementation of entropy as a gating criterion. This method assesses the randomness or uncertainty within an LLM’s response; higher entropy signals ambiguity, suggesting the model lacks confidence in its prediction. By filtering out responses exceeding a predetermined entropy threshold, the system effectively prioritizes forecasts grounded in greater certainty. This process isn’t simply about discarding data, but rather about focusing on the most robust and well-defined predictions, ultimately leading to a more consistent and trustworthy forecasting outcome. The application of entropy, therefore, functions as a quality control mechanism, ensuring that only confident and well-supported predictions contribute to the final forecast.

Large language models are emerging as potentially transformative tools for understanding and predicting complex societal trends. By analyzing vast quantities of textual data – news articles, social media posts, and public statements – these models can identify patterns and correlations indicative of future events in social and political spheres. This data-driven approach offers a compelling alternative to traditional forecasting methods, which often rely on expert opinion or limited datasets. The ability of LLMs to process information at scale and adapt to changing circumstances positions them as powerful instruments for social simulation, enabling researchers to explore “what if” scenarios and assess the potential impacts of various policies or events. Consequently, the application of these models promises a more nuanced and evidence-based understanding of the forces shaping human behavior and political outcomes.

Beyond Prediction: Refining the Model and Expanding the Scope

The predictive power of this model hinges on accurately representing individual viewpoints, and future work will concentrate on developing more detailed persona prompts. Current prompts, while functional, often simplify the complexities of human motivation and social behavior; refinements will explore incorporating factors like emotional reasoning, cognitive biases, and the influence of specific social contexts. Researchers anticipate that iterative testing and calibration of these prompts-perhaps leveraging large language models to generate nuanced responses-will yield increasingly realistic and reliable simulations of individual preferences and interactions, ultimately enhancing the model’s ability to forecast collective outcomes. A focus on capturing the subtle variations in how people weigh different values, and how those values shift in response to external stimuli, is expected to significantly improve the fidelity of the forecasts.

The precision of predictive models relying on value alignment can be substantially enhanced through advancements in how these values are quantified and understood. Current methods often rely on broad categorical assessments, but exploring techniques from computational linguistics and cognitive science – such as analyzing semantic networks or employing sentiment analysis with greater granularity – promises to reveal more nuanced value vectors. This could involve moving beyond simple positive or negative valuations to capture the intensity of preferences and the complex relationships between different values. Furthermore, incorporating methods that account for contextual factors – how values shift based on specific scenarios or social pressures – could significantly improve the robustness of forecasts, mitigating the risk of inaccurate predictions stemming from oversimplified representations of human motivation.

The predictive framework, currently demonstrated through analysis of consumer choices, holds considerable promise when applied to the complex landscape of political and social behaviors. Extending the model’s reach beyond commercial contexts allows for a deeper understanding of how collective values – represented as value vectors – shape public opinion and influence societal trends. Researchers posit that forecasting shifts in political sentiment, predicting the spread of social movements, or even anticipating responses to policy changes could become feasible through this expanded application. By identifying the underlying value structures driving these phenomena, the approach offers a potential pathway towards not simply observing public opinion, but proactively illuminating the forces that form it, offering crucial insights for policymakers, social scientists, and those seeking to understand the ever-evolving dynamics of human society.

The pursuit of predictive accuracy, as demonstrated in this work with latent representations and LLMs, inevitably courts the illusion of control. This research, probing the internal mechanisms of these models to forecast population preferences, reveals a system attempting to mirror, rather than dictate, collective behavior. It echoes a sentiment shared by Edsger W. Dijkstra: “It’s always possible to make things worse.” The very act of refining these predictive tools introduces new avenues for unforeseen consequences, for the amplification of existing biases, or the creation of novel vulnerabilities. A system that never mispredicts is, in effect, a system divorced from the messy reality it attempts to model – and thus, a dead one. The aggregation of latent representations isn’t about achieving perfect foresight, but about understanding the complex ecosystem of factors driving collective choice.

The Horizon Beckons

The pursuit of preference prediction, framed here through the lens of mechanistic forecasting, reveals a familiar truth: models are not oracles, but elaborate reflections of the data they consume. This work, by peering within the Large Language Model, suggests that aggregate representations-these ghostly echoes of partisan alignment-hold predictive power beyond simple output probabilities. Yet, this is not a triumph of control, but a restatement of dependency. The system doesn’t become more accurate; it becomes more transparently biased, its ‘intelligence’ merely a distillation of pre-existing social structures.

The temptation will be to refine these latent probes, to build ever more sophisticated instruments for measuring the contours of public opinion. But every new architecture promises freedom until it demands DevOps sacrifices. A more honest question is not how to predict, but what is being predicted. Preferences are fluid, contextual, and inherently chaotic. Order is just a temporary cache between failures.

Future work will inevitably attempt to generalize these findings beyond the political realm, to map the latent spaces of desire and aversion across diverse domains. This pursuit, however, risks mistaking correlation for causality, building increasingly elaborate simulations that obscure the fundamental unpredictability of collective behavior. The true challenge lies not in predicting the storm, but in learning to navigate the waves.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.02882.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Brown Dust 2 Mirror Wars (PvP) Tier List – July 2025

- Banks & Shadows: A 2026 Outlook

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- HSR 3.7 story ending explained: What happened to the Chrysos Heirs?

- ETH PREDICTION. ETH cryptocurrency

- 9 Video Games That Reshaped Our Moral Lens

- Gay Actors Who Are Notoriously Private About Their Lives

- Uncovering Hidden Groups: A New Approach to Social Network Analysis

2026-02-04 17:07