Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new benchmark challenges large language models with graph algorithm problems, exposing limitations in their ability to handle complex relational data and revealing a tendency to overthink.

Researchers introduce GrAlgoBench to rigorously evaluate long-context reasoning in large language models using problems rooted in graph theory.

Despite recent advances, evaluating the reasoning capabilities of large language models (LLMs) remains a challenge due to limitations in existing benchmarks. This is addressed in ‘Exposing Weaknesses of Large Reasoning Models through Graph Algorithm Problems’ by introducing GrAlgoBench, a novel benchmark utilizing graph algorithm problems to rigorously assess long-context reasoning. Systematic experiments reveal that current LLMs exhibit significant performance degradation with increasing graph complexity and suffer from an over-thinking phenomenon driven by excessive self-verification. Can graph algorithm problems serve as a more robust and insightful testbed for developing truly reasoning-capable LLMs?

The Limits of Scale: Reasoning’s Core Challenge

Despite their remarkable proficiency in generating human-quality text and performing various language-based tasks, Large Language Models (LLMs) often falter when confronted with reasoning challenges that demand multiple, interconnected steps. While adept at identifying patterns and recalling information, these models struggle to synthesize knowledge and draw logical conclusions across extended sequences of thought. This limitation isn’t necessarily a lack of knowledge, but rather a difficulty in effectively applying that knowledge in a structured, multi-stage problem-solving process. Essentially, LLMs can excel at recognizing individual pieces of a puzzle, but frequently stumble when assembling them into a coherent whole, particularly as the number of pieces-and the complexity of their relationships-increases. This becomes especially apparent in tasks requiring planning, deduction, or the nuanced understanding of cause and effect, revealing a critical gap between linguistic fluency and genuine reasoning capability.

Despite the remarkable progress in Large Language Models (LLMs) driven by increases in parameter count, simply building larger models does not consistently resolve fundamental limitations in reasoning. Studies indicate that while scale improves performance on many tasks, LLMs continue to struggle with processing information where relevant details are separated by considerable distance within a text – a phenomenon known as long-range dependency. This difficulty arises because the sequential nature of processing in these models can lead to information ‘decay’ as the model struggles to maintain contextual coherence across extended sequences. Consequently, even massively scaled LLMs can exhibit diminished accuracy and logical consistency when faced with tasks demanding the integration of information from disparate parts of a complex input, suggesting that architectural innovations, rather than sheer size, are crucial for achieving robust reasoning capabilities.

The difficulty large language models face when processing intricate information significantly impacts their ability to perform robust, multi-step reasoning. Domains such as scientific discovery, legal analysis, and complex logistical planning demand the synthesis of information from numerous sources and the careful tracking of dependencies between individual facts. When confronted with these challenges, models often exhibit a diminished capacity to maintain contextual coherence, leading to errors in inference and flawed conclusions. This isn’t simply a matter of needing more data; the models struggle with the architecture of complex problems, losing track of crucial details as the reasoning chain lengthens. Consequently, performance degrades rapidly as the number of required reasoning steps increases, highlighting a fundamental limitation in how these models currently navigate and utilize complex information landscapes.

Large language models typically process information in a linear, sequential manner, much like reading a book from beginning to end. However, this approach presents significant challenges when confronted with interconnected data – problems where understanding requires navigating relationships between numerous pieces of information. This sequential processing creates bottlenecks because the model must repeatedly revisit earlier data to establish context, slowing down problem-solving and increasing computational demands. Consequently, performance suffers in tasks demanding complex inferences, such as logical deduction or strategic planning, as the model struggles to efficiently manage and integrate information from across extended datasets. The inherent limitations of this architecture suggest that alternative processing methods are needed to unlock more robust and efficient reasoning capabilities in LLMs.

Graph Structures: A Natural Framework for Reasoning

Graphs are uniquely suited for representing interconnected data due to their structure of nodes and edges. Nodes represent entities – individuals, objects, concepts, or data points – while edges define the relationships between these entities. This allows for explicit modeling of associations, unlike traditional relational databases which often require joins to infer connections. The flexibility of graph structures accommodates diverse relationship types – directed, undirected, weighted, or unweighted – enabling the representation of complex networks. Consequently, graphs facilitate the visualization and analysis of relationships that are often implicit or difficult to discern in other data formats, making them a core component of knowledge representation and network analysis.

Graph algorithms provide a robust set of methods for processing data represented as graphs. Traversal algorithms, including Depth-First Search (DFS) and Breadth-First Search (BFS), systematically explore graph nodes and edges to visit all elements or find specific targets. Search algorithms, such as Dijkstra’s algorithm for shortest paths and A* search, efficiently locate optimal paths or nodes based on defined criteria and weighted edges. These algorithms are applicable to a wide range of problems, including network routing, social network analysis, recommendation systems, and database query optimization. The computational complexity of these algorithms varies based on graph size and structure, but established analyses exist to predict performance characteristics and guide algorithm selection for specific applications.

Representing reasoning tasks as graph problems enables the application of well-defined graph algorithms to facilitate complex analysis. This approach involves modeling entities as nodes and relationships between them as edges, transforming a logical problem into a structural one. Established algorithms – including shortest path, centrality measures, and community detection – can then be employed to identify patterns, infer connections, and ultimately derive conclusions from the data. The deterministic nature of these algorithms provides a transparent and repeatable methodology for reasoning, allowing for verifiable results and facilitating the automation of complex analytical processes. This paradigm is applicable across diverse domains, from knowledge representation and question answering to fraud detection and recommendation systems.

Breadth-First Search (BFS) is a graph traversal algorithm that systematically explores a graph level by level. Starting at a designated root node, BFS visits all immediate neighbor nodes before moving to the next level of neighbors. This process continues until the target node is found or the entire graph has been explored. BFS utilizes a queue data structure to manage the order of node visits, ensuring that nodes closer to the root are processed before those further away. The algorithm guarantees finding the shortest path-in terms of the number of edges-from the root node to any reachable node within an unweighted graph. This characteristic makes BFS particularly useful for applications requiring minimal-distance calculations or network broadcasting.

GraAlgoBench: A Benchmark for Algorithmic Reasoning

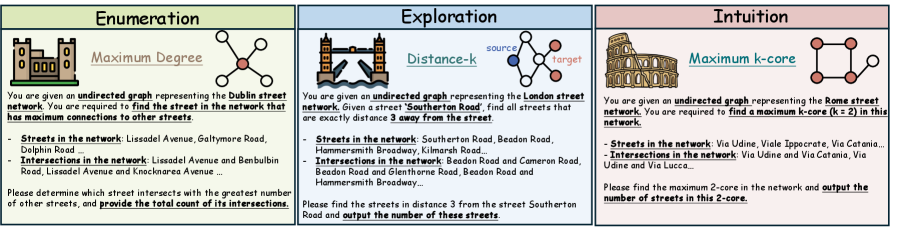

GraAlgoBench is a newly developed benchmark intended to evaluate the capacity of Large Language Models (LLMs) to resolve problems framed as graph algorithms. Unlike traditional benchmarks focusing on general knowledge or linguistic abilities, GraAlgoBench specifically tests an LLM’s ability to interpret problem statements requiring graph traversal and manipulation. The benchmark presents tasks defined using graph-based structures and necessitates the model to effectively translate natural language instructions into algorithmic steps for accurate execution on these graphs. This approach allows for a focused assessment of reasoning skills directly related to computational problem-solving, rather than relying on memorized patterns or statistical correlations within text data.

GraAlgoBench incorporates tasks that require models to perform established graph algorithm operations. Specifically, the benchmark includes problems centered around identifying the Minimum Spanning Tree (MST), a fundamental graph theory concept focused on connecting all vertices in a weighted graph with the minimum total edge weight. Additionally, tasks involve calculating the Maximum Triangle Sum within a graph, necessitating the identification of three connected nodes that yield the highest cumulative value based on assigned node weights. These tasks are designed to evaluate an LLM’s capacity to apply algorithmic principles to graph-structured data.

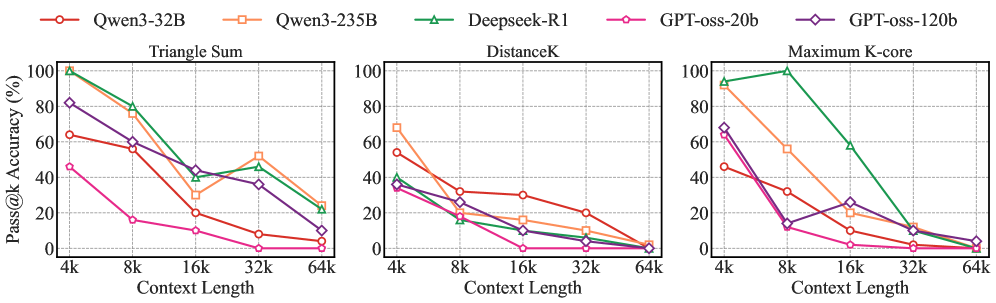

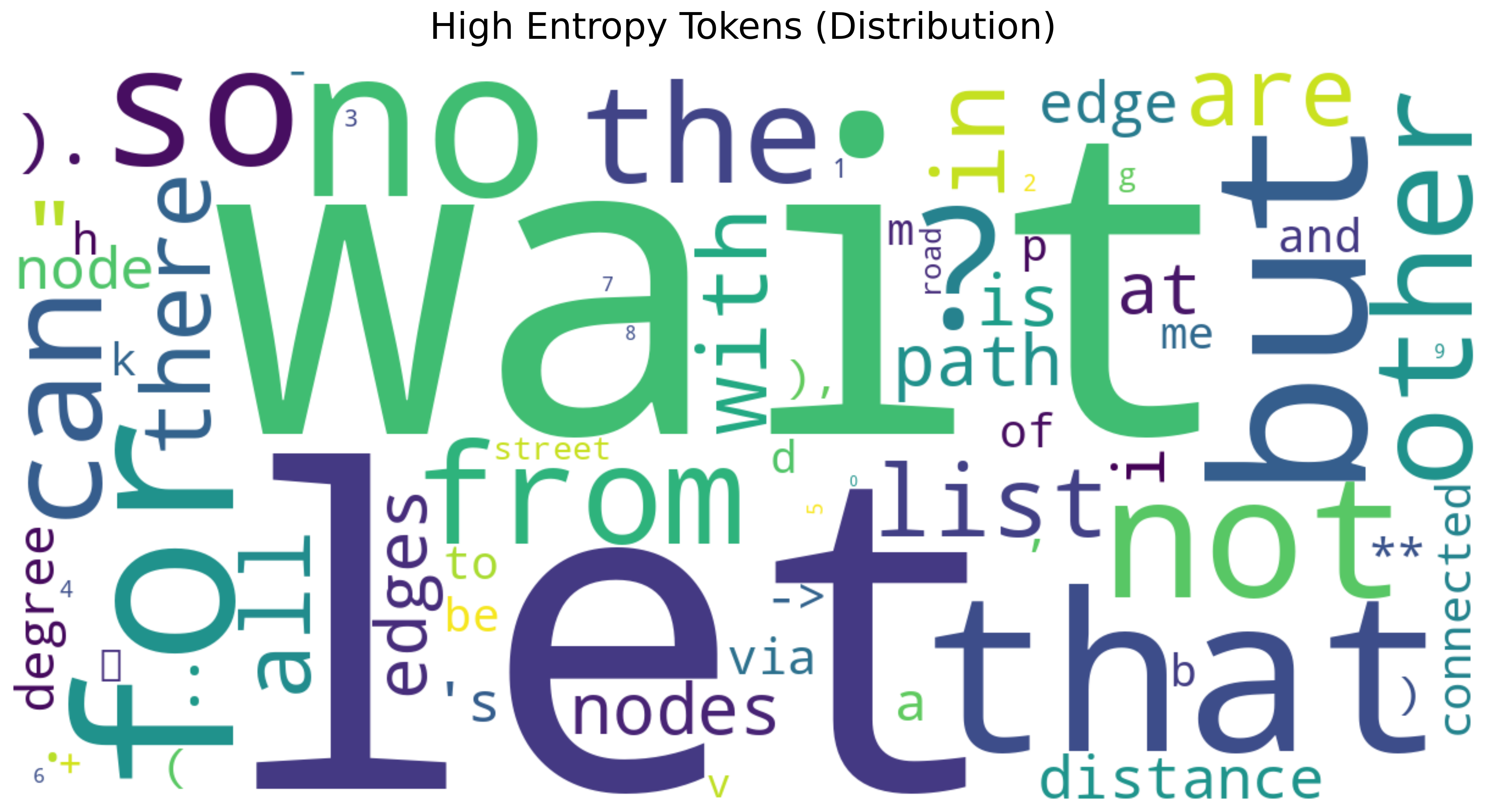

Evaluation using the GraAlgoBench benchmark indicates that current Large Language Models (LLMs) demonstrate difficulty with tasks necessitating systematic graph structure exploration. Specifically, LLMs frequently exhibit a tendency towards ‘overthinking’, generating excessively complex or irrelevant reasoning steps that detract from accurate problem-solving. This manifests as a failure to efficiently traverse graph nodes and edges, leading to incorrect outputs despite possessing the foundational knowledge to solve the underlying algorithmic problem. The observed behavior suggests limitations in the models’ ability to constrain reasoning within the defined problem space and prioritize essential steps for graph traversal and data manipulation.

Evaluation using GraAlgoBench quantifies an LLM’s capability to convert natural language problem descriptions into executable algorithmic steps; performance is measured using a Pass@k metric. Results indicate that the QWQ-32B model achieves a Pass@k rate of up to 87% on Level-3 tasks within the benchmark. However, analysis using a normalized Pass@k z-score reveals a consistent decline in performance as graph size increases, demonstrating that scaling LLM reasoning capabilities to larger and more complex graph structures remains a significant challenge.

Towards Robust Reasoning: Self-Verification and Algorithmic Foundations

Recent evaluations using GraAlgoBench have highlighted a critical need for enhanced self-verification within Large Language Models (LLMs). The benchmark consistently reveals that LLMs, while capable of generating plausible solutions, frequently stumble on fundamental errors in reasoning, particularly when tackling graph algorithms. This susceptibility isn’t necessarily due to a lack of knowledge, but rather an inability to consistently validate the correctness of their own outputs. Effective self-verification mechanisms – processes by which an LLM checks its work for logical consistency and adherence to problem constraints – are therefore paramount for mitigating these errors and significantly improving solution quality. Without such checks, even sophisticated LLMs can produce confidently incorrect answers, limiting their reliability in domains demanding precision and accuracy.

The application of established algorithms, such as Kruskal’s Algorithm, presents a compelling strategy for enhancing the reliability of large language models in solving complex problems. Kruskal’s Algorithm, a greedy method for finding the Minimum Spanning Tree for a weighted graph, provides a definitive, step-by-step process with a verifiable solution – a critical asset when integrated with the generative nature of LLMs. By grounding the LLM’s reasoning in this algorithmic framework, the system isn’t simply generating an answer, but constructing a solution along a proven pathway. This approach minimizes the potential for the LLM to introduce errors stemming from probabilistic reasoning, as each step can be validated against the known logic of the algorithm. The result is a more transparent and trustworthy problem-solving process, particularly valuable in domains demanding precision and accuracy, like network optimization and resource allocation, where a demonstrably correct solution is paramount.

The fusion of algorithmic rigor with the expansive potential of large language models promises a new era of dependable reasoning systems. Rather than relying solely on statistical correlations within vast datasets, integrating established algorithms – those with mathematically verifiable solutions – provides a grounding for LLM-driven problem-solving. This approach doesn’t aim to replace the generative strengths of these models, but to augment them with a layer of demonstrable correctness. By anchoring reasoning in proven methods, the resulting systems exhibit heightened reliability, minimizing the propagation of errors and fostering confidence in their outputs. Such hybrid architectures are poised to tackle complex challenges where accuracy is paramount, paving the way for advancements in fields like scientific inquiry and automated decision-making processes.

The potential of enhanced reasoning systems extends significantly into domains demanding intricate problem-solving capabilities, notably scientific discovery and automated decision-making processes. Recent findings highlight that deficiencies in self-verification mechanisms are a primary contributor to performance degradation within these systems; a robust ability to check and validate solutions is paramount. Investigations into network structures revealed that a Maximum Triangle Sum of 21 can be achieved through multiple interconnected triangles, indicating a pathway towards building more resilient and reliable computational models capable of navigating complex challenges and providing verifiable outcomes. This suggests a future where automated systems not only generate solutions, but also demonstrably confirm their accuracy, fostering greater trust and accelerating progress in critical fields.

The evaluation detailed within rigorously exposes limitations in current Large Language Models when confronted with graph algorithm problems, highlighting a tendency toward overthinking rather than efficient problem-solving. This aligns with Ken Thompson’s observation: “There’s no reason to have a complex system when a simple one will do.” The GrAlgoBench benchmark, by design, strips away extraneous information, demanding precise reasoning over complex graphs-a task where unnecessary computation actively hinders performance. The study demonstrates that density of meaning, achieved through focused problem definition, is crucial; extraneous ‘thought’ becomes violence against attention, obscuring the optimal solution path.

Beyond the Graph

The introduction of GrAlgoBench serves not as a culmination, but as a necessary subtraction. The benchmark’s value lies not in demonstrating what these large models can do-a capability increasingly apparent-but in clarifying the precise nature of their failures. The observed tendency toward “overthinking” suggests a fundamental miscalibration in the cost function governing these systems; complexity, it seems, is not always rewarded with accuracy. Future work must therefore prioritize the development of metrics that penalize unnecessary computational expenditure, effectively rewarding elegance in solution construction.

A persistent limitation remains the artificiality of the task. While graph algorithms provide a controlled environment for evaluation, the disconnect between these abstract problems and real-world reasoning scenarios is substantial. The field should consider benchmarks that integrate graph-based reasoning into more ecologically valid contexts-problems where the graph structure is implicit, derived from natural language, or embedded within a broader knowledge representation.

Ultimately, the pursuit of intelligence is a process of iterative refinement through negative constraints. Each exposed weakness-each instance of “overthinking” or inability to navigate complex graph structures-is not a failure, but a deletion of unnecessary complexity. The goal is not to build ever-larger models, but to sculpt them with increasing precision, revealing the essential core of reasoning itself.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.06319.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Top 15 Insanely Popular Android Games

- Did Alan Cumming Reveal Comic-Accurate Costume for AVENGERS: DOOMSDAY?

- 4 Reasons to Buy Interactive Brokers Stock Like There’s No Tomorrow

- EUR UAH PREDICTION

- Silver Rate Forecast

- DOT PREDICTION. DOT cryptocurrency

- ELESTRALS AWAKENED Blends Mythology and POKÉMON (Exclusive Look)

- New ‘Donkey Kong’ Movie Reportedly in the Works with Possible Release Date

- Core Scientific’s Merger Meltdown: A Gogolian Tale

2026-02-10 07:48