The story of American movies usually focuses on big studios, leaving out the important work of Black filmmakers who created films independently. For many years, these innovative films were held back by censorship, unfair distribution, or simply lost because no one preserved them. They offered complex and realistic portrayals of Black life, which differed from the often stereotypical stories preferred by Hollywood. Thankfully, recent restoration work and independent archives are now bringing these forgotten films back for everyone to see, revealing a powerful history of creative resistance.

‘Within Our Gates’ (1920)

This silent film, directed by Oscar Micheaux, was believed to be lost for many years until a copy was found in Spain in the 1970s. It directly challenges the racist portrayal in ‘The Birth of a Nation’ by showing the harsh realities of lynching and segregation. When it was first released, it faced significant censorship because officials worried it would cause racial tension. Now, it’s celebrated as the earliest known feature-length film made by an African-American director and an important piece of history.

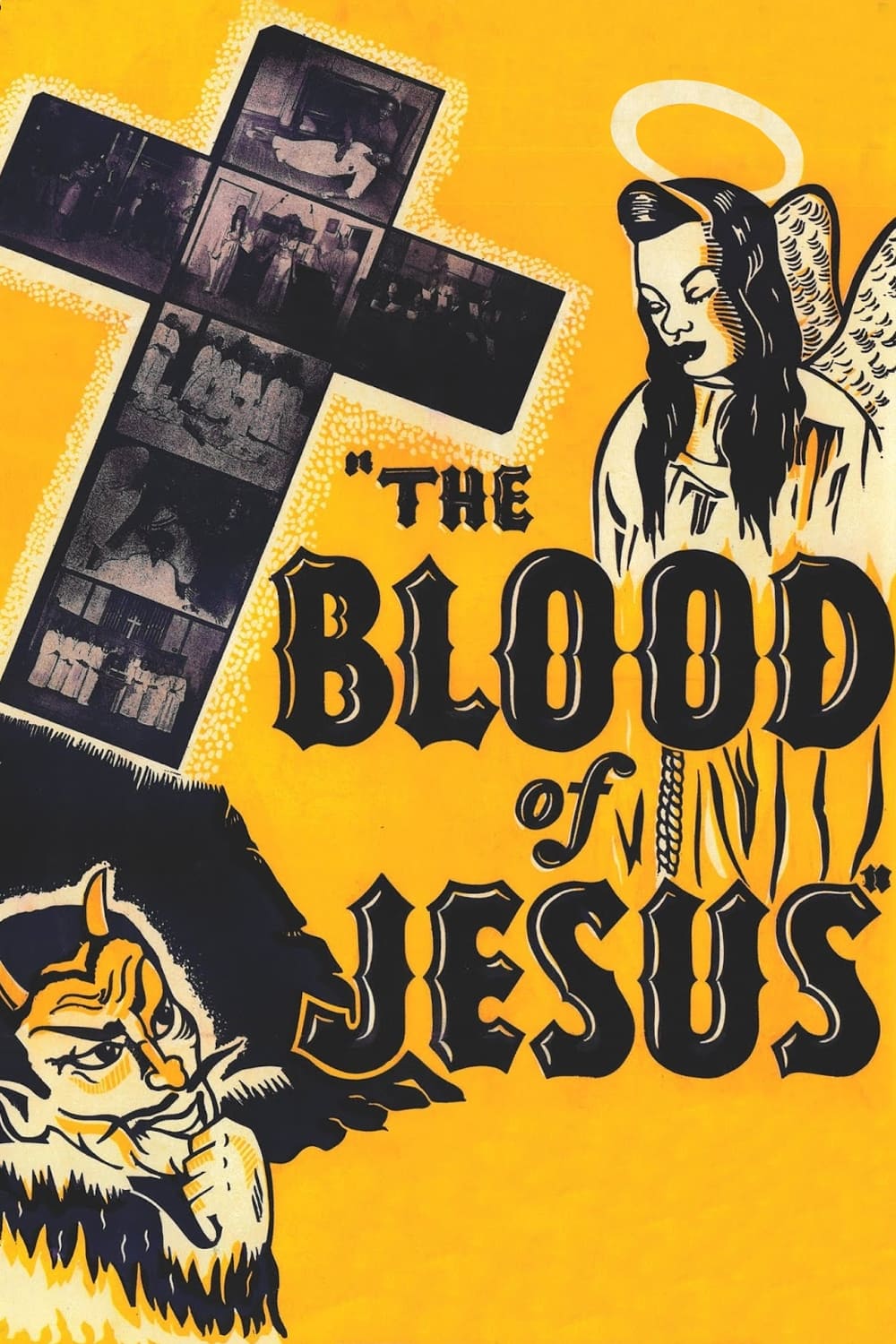

‘The Blood of Jesus’ (1941)

Spencer Williams created and starred in this film, made for Black audiences during segregation. Originally shown in southern theaters and churches, it was lost for many years until a copy was rediscovered in a warehouse in the 1980s. The film tells the story of a woman’s spiritual journey, using religious themes and elements of folk culture. Its importance to American culture led to it being the first “race film” added to the National Film Registry.

‘Hell-Bound Train’ (1930)

Created by James and Eloyce Gist, this silent film was designed to spread religious messages within Black communities. It uses the metaphor of a train – each car symbolizing a different sin – to show the path to destruction. The film wasn’t made for mainstream movie theaters, but was shown in places like community centers. Thankfully, the Library of Congress restored this unusual footage from its original 16mm format, saving an important piece of early Black surrealist filmmaking.

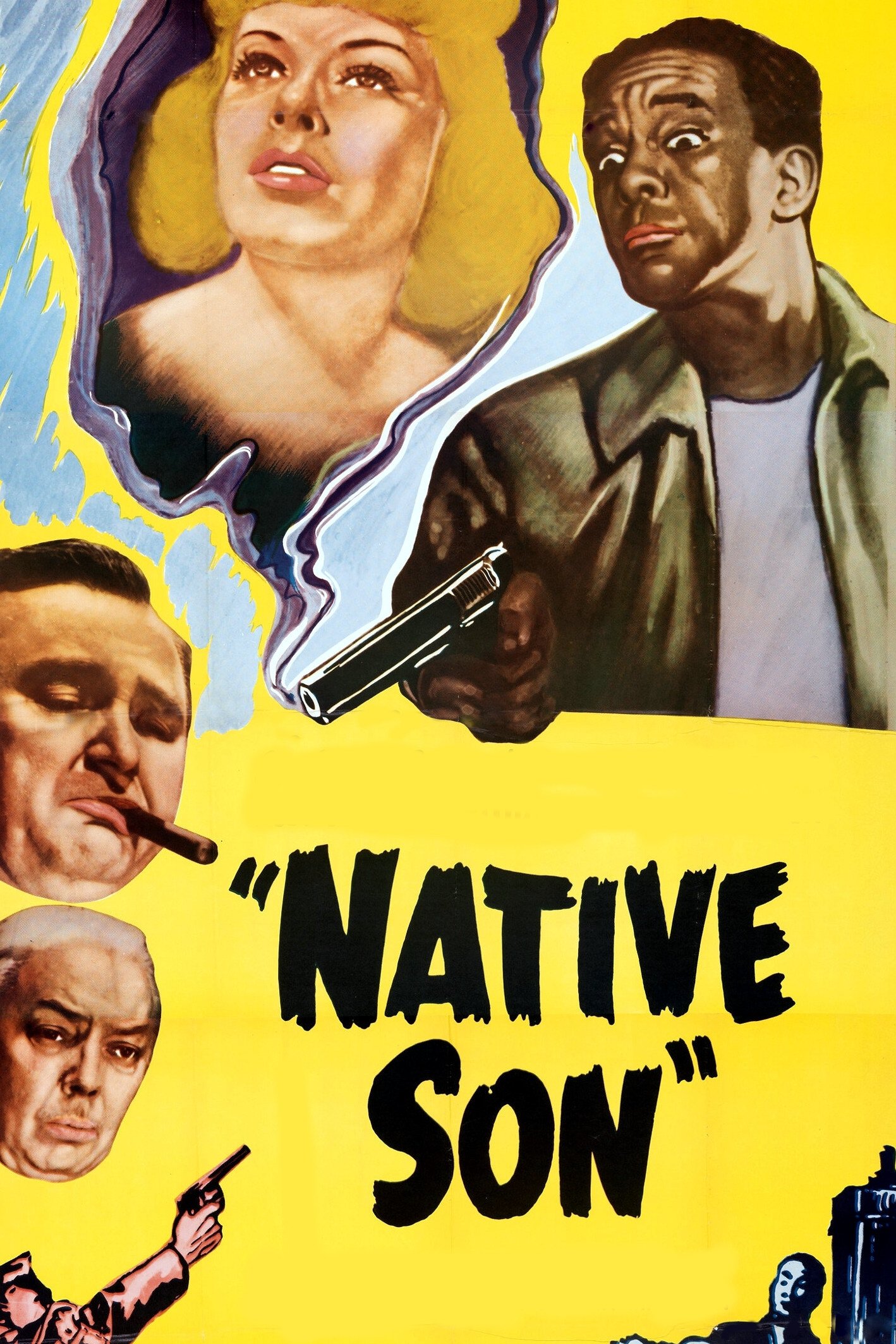

‘Native Son’ (1951)

This movie, based on Richard Wright’s novel, was filmed in Argentina due to political issues that prevented production in the United States. When it was released in America, it underwent significant censorship, losing many of its powerful criticisms of society. Richard Wright, the author, plays the lead role of Bigger Thomas, a young man struggling with poverty and ongoing violence. The complete, original version of the film, which had been lost for years, was recently found and restored.

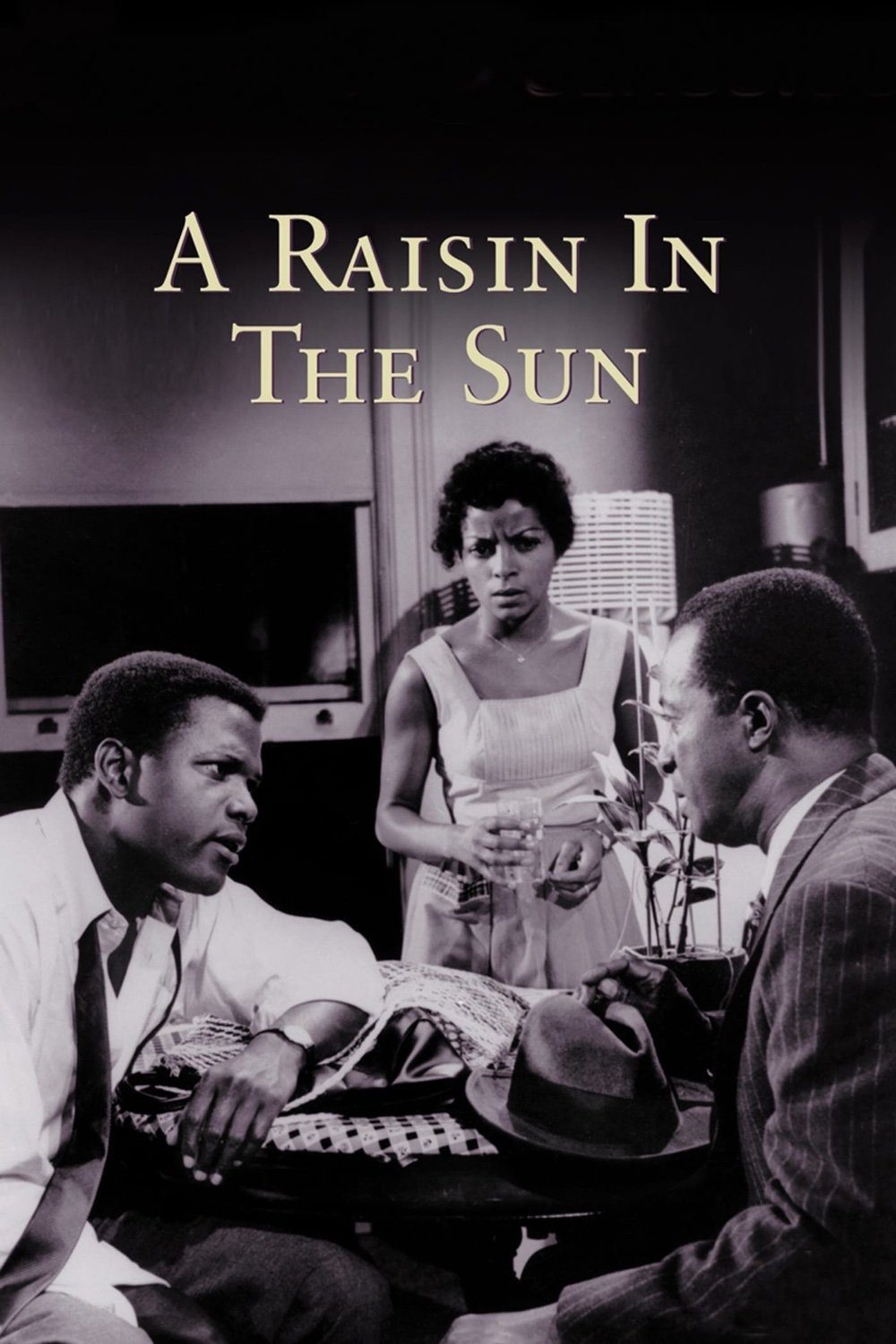

‘A Raisin in the Sun’ (1961)

I’ve always been captivated by this film, especially knowing the hurdles it overcame. Apparently, even though it was based on a successful play, studio heads worried a white audience wouldn’t connect with a story about a Black family’s life. They actually changed the script multiple times, trying to soften the social message to appeal to more people. But despite all that, it still powerfully captures the fight for a better life and the realities of housing discrimination in Chicago. And honestly, the acting – Sidney Poitier and Claudia McNeil are just phenomenal. It’s incredible to think their performances weren’t immediately embraced – now, they’re rightly considered legendary!

‘Nothing But a Man’ (1964)

This compelling drama tells the story of a railroad worker in Alabama, and it was notable for its realistic portrayal of characters – a refreshing change from the stereotypes common in 1960s films. Despite being a well-made film, it struggled to find an audience because it didn’t fit the typical expectations for movies with Black leads, which were often expected to be overtly political. Featuring Ivan Dixon and Abbey Lincoln, the film powerfully and subtly explores the challenges of preserving one’s self-respect in the face of systemic racism. It was a film admired by Malcolm X and continues to be celebrated as an important example of independent filmmaking due to its genuine and honest approach.

‘Symbiopsychotaxiplasm: Take One’ (1968)

William Greaves’ film is a groundbreaking blend of documentary and fiction, known for its unconventional structure. Lost for many years, it was rediscovered in the early 2000s thanks to actors Steve Buscemi and Danny Glover. The film uniquely captures a film crew at work, while another crew films them, offering a fascinating look at how movies are made. Today, it’s celebrated as a key work of American experimental cinema and a surprising predecessor to modern reality TV.

‘The Learning Tree’ (1969)

Gordon Parks made history as the first Black director to lead a major film studio production, adapting his own semi-autobiographical novel for the screen. While Warner Bros.-Seven Arts financed the project, its gentle and reflective style didn’t easily fit with the fast-paced action films popular at the time. The movie portrays a boy’s childhood in 1920s Kansas, focusing on his developing understanding of racial issues. It’s remembered for its stunning visuals and its honest depiction of the challenges and nuances of life in a rural setting.

‘Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song’ (1971)

Melvin Van Peebles was the driving force behind this groundbreaking film, handling everything from producing and directing to composing the music and starring in it. It’s considered the film that launched the Blaxploitation genre. Though initially given an X rating, Van Peebles cleverly used this to draw in Black viewers. Because major film studios wouldn’t take a chance on the project, he released it himself in just two theaters. It went on to become a huge independent success, demonstrating that there was a large Black audience that had been largely ignored.

‘Buck and the Preacher’ (1972)

Sidney Poitier’s first time directing was this Western, which aimed to show the often-overlooked contributions of Black pioneers in the American West. Poitier insisted on having creative control to make sure the film truthfully portrayed the lives of Black people after the Civil War. The movie centers on a former soldier and a trickster who work together to help escaped slaves find a new life on the frontier. This role was a big change for Poitier, as he was usually cast in parts that asked him to fit into mainstream white society.

‘The Spook Who Sat by the Door’ (1973)

I recently had the chance to see a film with a fascinating history. Originally released back in the early 70s, it was shockingly pulled from cinemas just weeks after hitting screens. Apparently, the FBI leaned on United Artists because of its pretty radical themes – think revolution and guerilla warfare. For years, the only way to see it was through grainy bootlegs! Thankfully, it’s been beautifully restored digitally. The plot centers around a highly skilled Black operative, trained by the CIA, who decides to use those skills to spark a rebellion right in the heart of Chicago. It’s a gripping story with a seriously interesting backstory.

‘Ganja & Hess’ (1973)

Originally premiering to acclaim at Cannes, this unique horror film was unfortunately altered by its producers and released as a standard vampire movie called ‘Blood Couple’. Director Bill Gunn intended the film’s use of blood to represent both addiction and the challenges of fitting into mainstream culture for African Americans. The original, artistic version was almost lost to time, but has been carefully preserved by the Museum of Modern Art. It’s now recognized as a significant achievement in Black independent filmmaking, celebrated for its beautiful visuals and thought-provoking themes.

‘Claudine’ (1974)

This movie provided a realistic and moving portrayal of a single mother raising six children and dealing with the challenges of the welfare system. Despite earning Diahann Carroll an Academy Award nomination, many critics at the time mistakenly grouped it with cheaper action films. The filmmakers aimed to show the humanity of a group of people who were often unfairly criticized or overlooked in the media. Its combination of lighthearted romance, comedy, and honest social commentary was unusual for a major studio film of the mid-1970s.

‘Uptown Saturday Night’ (1974)

Sidney Poitier’s action-comedy brought together a huge cast of prominent Black actors, like Bill Cosby and Richard Pryor. Though it did well in theaters, many mainstream critics didn’t appreciate its focus on Black humor and experiences. The film was one of three intended to showcase positive and uplifting stories about Black life. It also helped popularize the buddy-cop and ensemble comedy styles that would become very common in the 1980s.

‘Cooley High’ (1975)

Set in 1960s Chicago, this film offered a realistic take on teenage life as a counterpoint to the popular Blaxploitation films of the time. While it resonated with audiences and inspired later filmmakers, it’s often been overlooked when discussing the best American teen movies. The story, about friendship and loss, is powerfully told with a nostalgic feel and a soundtrack filled with Motown classics. It’s still cherished today for its honest and genuine depiction of Black teenagers and city life.

‘Passing Through’ (1977)

Larry Clark’s film is widely considered a stunning portrayal of jazz. However, because of difficulties securing music rights and the director’s insistence on complete artistic freedom, it wasn’t shown in many theaters. The story centers on a young saxophonist’s quest to find his musical idol while staying true to his artistic vision. Its rarity over the years has made it a beloved and legendary film for serious movie fans and jazz experts.

‘Killer of Sheep’ (1978)

Charles Burnett made this film in the Watts neighborhood of Los Angeles as his graduate school project, working with very little money. For almost 30 years, it couldn’t be shown in theaters because it was too expensive to secure the rights to the music used in it. The film tells the story of a man working in a slaughterhouse and his efforts to keep his family together and maintain their dignity. Now recognized as a landmark achievement in American cinema, it’s been preserved in the National Film Registry.

‘Bush Mama’ (1979)

Haile Gerima’s film offers a powerful and realistic depiction of hardship and systemic injustice in 1970s Los Angeles, specifically within the Watts neighborhood. Made as part of the L.A. Rebellion film movement, it follows a woman’s struggles with welfare and encounters with police brutality. Due to its politically charged content and independent production, the film wasn’t widely released, mainly being shown at film festivals. It remains a stark and unflinching portrayal of the social and political realities of the time.

‘Personal Problems’ (1980)

Created by Ishmael Reed and directed by Bill Gunn, this unique film—often described as a ‘soap opera about soap operas’—was originally made on video tape. Though intended for public television, it was mostly ignored by the mainstream film industry for many years. The film offers a realistic and spontaneous look at the everyday lives of Black New Yorkers. A restoration in 2018 brought it to a wider audience and helped establish Bill Gunn’s important place in film history.

‘Losing Ground’ (1982)

Kathleen Collins’s film is a landmark achievement, notable as one of the first feature films directed by a Black woman. Though critically praised, it wasn’t shown in theaters and remained hidden for over three decades. The film delves into the complex inner world of a philosophy professor as she navigates her marriage and rediscovers her own creativity. It was beautifully restored and widely celebrated in 2015, many years after Collins’s passing.

‘Cane River’ (1982)

Horace B. Jenkins wrote and directed this moving love story, but sadly passed away soon after finishing it. The film wasn’t shown and was thought to be lost forever, until a copy was found in a New York vault in 2013. It’s about a romance between two young Black people from different backgrounds in rural Louisiana. When it was restored in 2020, it became clear that the film offered a surprisingly insightful look at issues like prejudice based on skin color and the importance of land ownership – themes that were remarkably progressive for its time.

‘Chameleon Street’ (1991)

Wendell B. Harris Jr.’s satirical film won the top prize at the Sundance Film Festival, but surprisingly, Hollywood studios wouldn’t distribute it, believing it was too challenging for mainstream audiences. The movie is based on the true story of a con artist who convincingly posed as various professionals, including doctors, lawyers, and journalists. After self-releasing the film, it remained relatively unknown until a recent high-quality 4K restoration brought it renewed attention.

‘Tongues Untied’ (1989)

Marlon Riggs’s groundbreaking documentary gave a strong voice to Black gay men. When it aired on public television, it sparked intense controversy and led to debates in Congress over funding for the arts. The film boldly combines poetry, dance, and music to challenge both racism and homophobia in America. Its powerful and frank content led to it being blocked from airing in many areas.

‘To Sleep with Anger’ (1990)

This family drama was made possible with financial support from Danny Glover and directed by acclaimed filmmaker Charles Burnett. Though critics loved the film, its distributor had trouble finding an audience for its unique mix of Southern folklore and realistic family life. The story centers on a stranger from the South who unexpectedly changes the lives of a Black family in Los Angeles. Many consider it a deeply meaningful and important film in American cinematic history.

‘Daughters of the Dust’ (1991)

Julie Dash’s film was groundbreaking as the first feature directed by an African-American woman to play in many theaters across the U.S. However, despite this achievement, it was difficult to find studios willing to distribute the film widely, as they didn’t believe it would appeal to audiences outside of the Black community. The story beautifully portrays three generations of women from the Gullah community in South Carolina as they get ready to move away from their island home. Its stunning visuals and unique storytelling style later inspired artists like Beyoncé, influencing her visual album ‘Lemonade’.

‘Deep Cover’ (1992)

As a film fan, I always loved this movie. It’s a gritty noir thriller directed by Bill Duke, and Laurence Fishburne is fantastic as an undercover cop going deep into the drug world. Honestly, when it first came out, it was sold as just another action flick, but it’s so much more than that. It’s a really smart take on the war on drugs and how messed up the system is. Back then, a lot of critics missed the deeper stuff – the complicated moral choices and the philosophical questions it raises. But now, people are finally recognizing it as a true 90s crime masterpiece, especially because of its really powerful political message.

‘The Watermelon Woman’ (1996)

Cheryl Dunye’s film is a groundbreaking achievement, being the first feature-length movie directed by an openly Black lesbian. It sparked controversy when a politician criticized public funding for the project. The film centers on a young filmmaker’s search for a Black actress from the 1930s who was frequently typecast. Today, it’s recognized as a vital piece of both Black and LGBTQ+ film history.

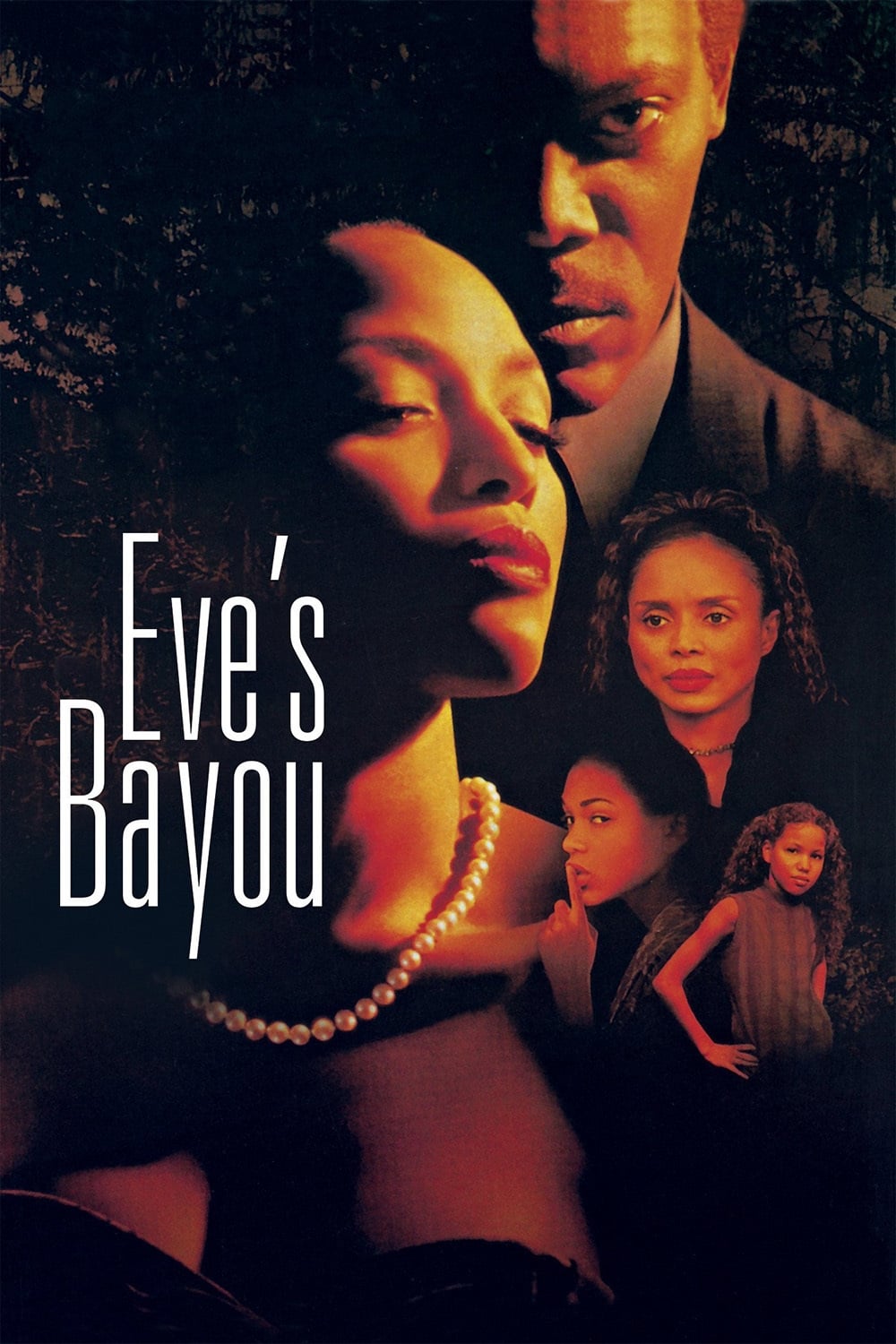

‘Eve’s Bayou’ (1997)

Kasi Lemmons’ first film as a director is a Southern Gothic drama set in 1960s Louisiana. Though critics loved it and it became the most successful independent film of its year, it didn’t receive much attention from major award shows. The story unfolds from the perspective of a young girl who learns about her father’s affairs and the mysterious, supernatural side of her family. Years later, the Library of Congress acknowledged its important artistic and cultural value.

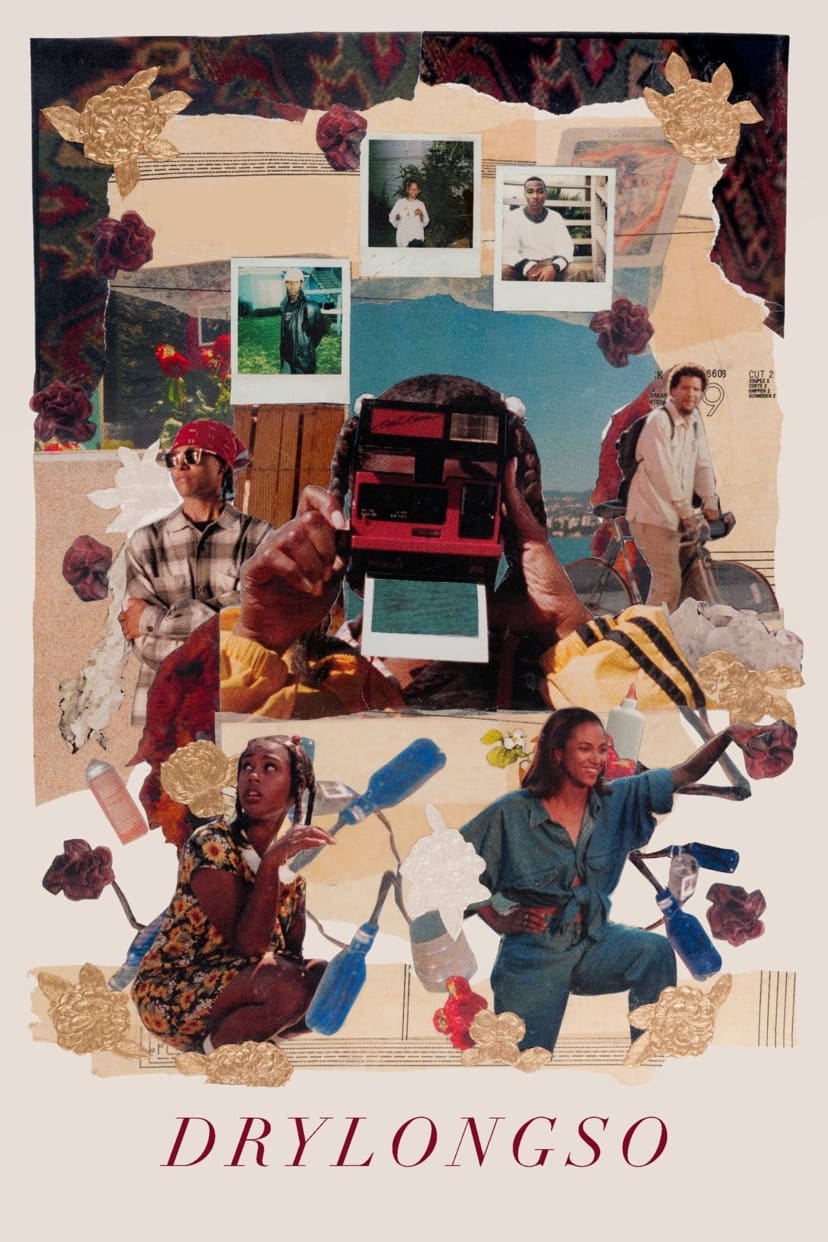

‘Drylongso’ (1998)

Cauleen Smith’s first feature film received positive attention at the Sundance Film Festival, but it took several years to find a distributor. The film centers on a young art student in Oakland who photographs Black men as a way to document their lives amidst local violence. Its distinctive, independent style, reflective of a particular time and place in the 90s, wasn’t appreciated by major studios at the time. However, a recent restoration has reintroduced the film to audiences and sparked renewed interest.

Read More

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Wuchang Fallen Feathers Save File Location on PC

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Brown Dust 2 Mirror Wars (PvP) Tier List – July 2025

- Where to Change Hair Color in Where Winds Meet

- Crypto Chaos: Is Your Portfolio Doomed? 😱

- HSR 3.7 breaks Hidden Passages, so here’s a workaround

- Macaulay Culkin Finally Returns as Kevin in ‘Home Alone’ Revival

- Solel Partners’ $29.6 Million Bet on First American: A Deep Dive into Housing’s Unseen Forces

- The Best Single-Player Games Released in 2025

2026-02-18 06:18