There is a peculiar sort of beauty in stocks that refuse to bloom. While the market dances after the glitter of quantum computing and AI promises, the frozen food industry remains a frostbitten relic-practical, unglamorous, and quietly enduring. Nomad Foods, a company that sells frozen peas and chicken nuggets, has fallen 63% from its peak. One might call it a tragedy, or perhaps a miscalculation. Either way, it lingers in the cold.

Nomad Foods: Europe‘s Leader in Frozen Foods

Nomad Foods, a British enterprise, owns the Birds Eye and Findus brands. It is the largest frozen foods manufacturer in Europe, a fact that seems both impressive and absurd in an age where investors crave the next big thing. The company’s revenue is split between protein and vegetables, a decision that might be described as prudent-or, in the parlance of Wall Street, “positioning for the health-conscious consumer.” One wonders if the same logic applies to selling dehydrated potatoes in a world increasingly preoccupied with kale smoothies.

1. Optimizing Capacity

Since 2015, Nomad has acquired five companies, a strategy that often leads to the kind of operational chaos one associates with family dinners and holiday gatherings. Now, the company is attempting to streamline its logistical chain, reduce depots, and increase production capacity from 66% to something slightly less pitiful. Management speaks of $200 million in savings by 2028, a sum that sounds generous until one considers the cost of maintaining a fleet of refrigerated trucks in a climate prone to rain and existential dread.

2. Share Buybacks

If the cost savings materialize-and there is no guarantee they will-Nomad plans to use the proceeds for share repurchases. The company has bought back 4% of its shares annually since 2021, a gesture that could be interpreted as confidence or desperation. At current valuations, these buybacks resemble a man purchasing a secondhand coat to appear less destitute in public. Still, there is a certain dignity in the act.

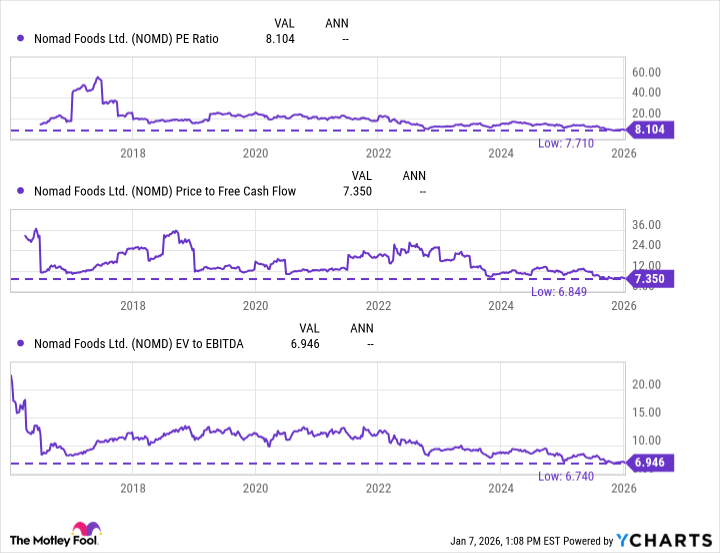

3. A Once-in-a-Decade Valuation

By most metrics, Nomad trades at a decade-low valuation. The company’s enterprise value is $4 billion, a number that feels both vast and meaningless in the context of frozen food. Its stock price suggests a business on the brink of extinction, despite five years of 6% annual sales growth. One might argue that the market is simply acknowledging the inherent risks of selling frozen meals in a world where people increasingly cook their own dinners. Or perhaps it is a mistake. Time will tell.

4. Even Management Is Buying the Stock

Martin Franklin, the company’s co-founder, has declared the stock “unusually cheap.” During the third-quarter earnings call, he spoke of share repurchases as the “primary use of cash flow after dividends.” Meanwhile, CFO Ruben Baldew purchased $1 million in Nomad stock with his own money, a gesture that could be read as either courage or optimism. One imagines him sipping tea in a dimly lit office, surrounded by spreadsheets and the faint smell of fish fingers.

5. An Ultra-High-Yield Dividend

Nomad’s dividend yield now stands at 5.8%, a figure that would make even the most jaded investor pause. The payments consume only 46% of net income, leaving room for further buybacks. The company has raised its dividend 13% this year, a performance that might be described as modest. Yet, in a world where many stocks offer nothing but vapor, 5.8% feels almost like a promise.

A Patient Buy for Me

I have added to my Nomad position this year and plan to hold it for three to five years, perhaps longer. The snow melts slowly in Europe, and so too does the company’s redemption. For now, I collect the dividend and watch as management buys back shares at a valuation that defies logic. There is a quiet hope here, a belief that the market will one day remember the value of steady hands and frozen vegetables. Until then, I wait. ❄️

Read More

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Brown Dust 2 Mirror Wars (PvP) Tier List – July 2025

- Banks & Shadows: A 2026 Outlook

- Gemini’s Execs Vanish Like Ghosts-Crypto’s Latest Drama!

- Wuchang Fallen Feathers Save File Location on PC

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- QuantumScape: A Speculative Venture

- ETH PREDICTION. ETH cryptocurrency

- Uncovering Hidden Groups: A New Approach to Social Network Analysis

2026-01-10 18:43