The market, my dear friends, has been enjoying a most unbecoming display of optimism these past seven years. The S&P 500, that barometer of collective folly, has managed a respectable ascent in all but one annum. The Dow Jones, a relic of a bygone era, and the Nasdaq, that playground of speculative excess, have both climbed to heights that suggest a regrettable lack of imagination. It is, of course, precisely when things appear most secure that one should begin to polish the life raft.

The impending transition at the Federal Reserve promises a spectacle of no small interest. Jerome Powell’s tenure draws to a close, and his predecessor, a man of predictable temperament, has viewed his stewardship with a distinct lack of enthusiasm. The appointment of Kevin Warsh, therefore, is less a surprise than the inevitable consequence of a world determined to repeat its errors with ever-increasing extravagance.

Mr. Warsh, it is said, is intended to soothe the anxieties of Wall Street. A veteran of the Federal Open Market Committee, he possesses the requisite experience – though one might argue that experience is merely the art of making the same mistakes with greater efficiency. His record, however, suggests a gentleman of rather…firm convictions, and it is conviction, you see, that often leads to catastrophe.

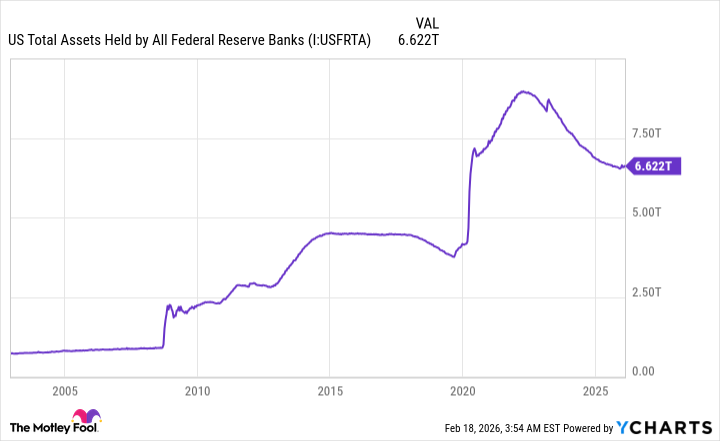

Mr. Warsh, it seems, views the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet – that monstrous accumulation of six and a half trillion dollars – with a decided lack of affection. He believes, quite rightly perhaps, that the central bank should not be meddling in the markets. A perfectly sensible notion, of course, though rather like demanding that a peacock refrain from displaying its plumage. It is, after all, in its nature.

The reduction of this balance sheet – the selling of Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities – is where the trouble begins. It is a simple matter of supply and demand, you see. Less demand for bonds means higher yields, and higher yields mean…well, let us simply say that borrowing becomes less of a pleasure and more of a necessity. The market, naturally, dislikes necessities.

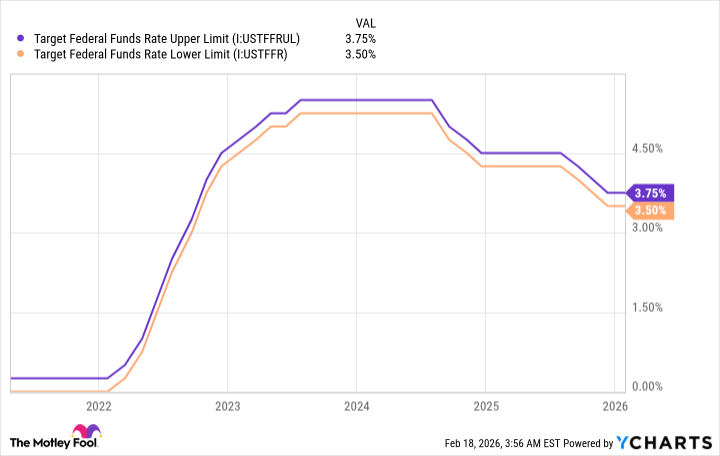

One might argue that lower interest rates are merely a postponement of the inevitable. But the market, my dear friends, is rarely concerned with logic. It prefers the illusion of prosperity to the reality of prudence. And it will punish any attempt to disturb its delusions.

However, the true danger lies not in Mr. Warsh’s policies, but in the fractured state of the Federal Open Market Committee. A unified front, even a misguided one, is far more reassuring than a chorus of dissenting voices. The recent meetings have been marked by a rather alarming degree of disagreement – a veritable Babel of economic opinion. To have members pulling in opposite directions is akin to navigating a ship with two captains – a recipe for disaster, naturally.

Mr. Warsh, it appears, places a greater emphasis on price stability than on employment. A perfectly reasonable position, of course, though rather like admiring the wallpaper while the house is on fire. One must, after all, prioritize. But to ignore the plight of the unemployed is to court social unrest – a rather unpleasant prospect for any investor.

The appointment, it must be said, is far from certain. The Senate Banking Committee, a body not known for its decisiveness, must first approve his nomination. And even then, a majority vote in the Senate is required. But should Mr. Warsh overcome these hurdles, one can expect a period of considerable turbulence. The market, you see, dislikes surprises. And Mr. Warsh, I suspect, is a man who enjoys them immensely.

To lose one billion dollars may be regarded as a misfortune; to lose two looks like carelessness. And to appoint a central banker who actively seeks to disrupt the prevailing complacency? Well, that, my dear friends, is simply good theatre.

Read More

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Brown Dust 2 Mirror Wars (PvP) Tier List – July 2025

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Wuchang Fallen Feathers Save File Location on PC

- Banks & Shadows: A 2026 Outlook

- Gemini’s Execs Vanish Like Ghosts-Crypto’s Latest Drama!

- HSR 3.7 breaks Hidden Passages, so here’s a workaround

- Exit Strategy: A Biotech Farce

- MicroStrategy’s $1.44B Cash Wall: Panic Room or Party Fund? 🎉💰

- QuantumScape: A Speculative Venture

2026-02-21 14:42