Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers are leveraging the power of graph neural networks to decode the complex activity of simulated brain regions and reveal the underlying principles of neural computation.

Graph neural networks successfully infer connectivity, functional roles, and external stimuli from time-series data of simulated neural assemblies.

Decomposing the activity of complex neural systems remains a significant challenge, often requiring trade-offs between predictive power and mechanistic interpretability. This is addressed in ‘Graph neural networks uncover structure and functions underlying the activity of simulated neural assemblies’, which introduces a novel framework leveraging graph neural networks to infer both the structure and dynamics of large-scale neural activity. The authors demonstrate that their approach can simultaneously recover connectivity matrices, neuron types, signaling functions, and even hidden external stimuli from observed neural dynamics. Could this method provide a pathway toward truly interpretable models of neural computation and ultimately, a deeper understanding of brain function?

The Fragility of Abstraction: Beyond Simplistic Neural Models

Conventional computational neuroscience frequently relies on abstractions of neural interactions, often treating neurons as simple input-output devices or reducing synaptic connections to mere weighted sums. While these simplifications enable researchers to model large networks, they inherently discard critical information about the rich, dynamic processes occurring within and between neurons. This loss of detail obscures the nuanced interplay of temporal dynamics, dendritic computations, and synaptic plasticity – all of which profoundly shape network behavior. Consequently, models built on these assumptions may fail to capture essential features of neural computation, such as the emergence of complex patterns, the sensitivity to noise, and the adaptability of biological systems. A growing body of evidence suggests that these seemingly minor omissions can lead to significant discrepancies between model predictions and experimental observations, highlighting the need for more biologically realistic and computationally tractable approaches.

The functional behavior of a neural assembly – a group of interconnected neurons – isn’t simply the sum of its parts; it arises from the intricate web of connections and the unique characteristics of each neuron within it. Recent research demonstrates that accurately modeling these assemblies demands a departure from generalized network representations. Instead, computational approaches must incorporate the specific connectivity patterns – the strength and type of synaptic connections – alongside individual neuronal properties like firing thresholds, membrane resistance, and dendritic morphology. Failing to account for these nuances can lead to simulations that drastically misrepresent the assembly’s actual response to stimuli, obscuring crucial insights into neural computation and information processing. This necessitates the development of techniques capable of handling both the detailed biophysics of individual neurons

Current computational neuroscience faces a significant challenge in reconciling the detail of biophysical models with the need for large-scale simulations. While highly detailed models can accurately represent the behavior of individual neurons – incorporating factors like ion channel dynamics and synaptic plasticity – they are computationally expensive, limiting the size of networks that can be realistically simulated. Conversely, simplified models, capable of simulating vast networks, often sacrifice biological realism, potentially missing crucial emergent properties arising from complex interactions. This disconnect hinders a comprehensive understanding of neural systems; researchers are actively exploring novel approaches – including multi-scale modeling and neuromorphic computing – to bridge this gap and enable simulations that are both biologically plausible and computationally tractable, ultimately aiming to capture the full spectrum of neural behavior from single neuron dynamics to large-scale brain function.

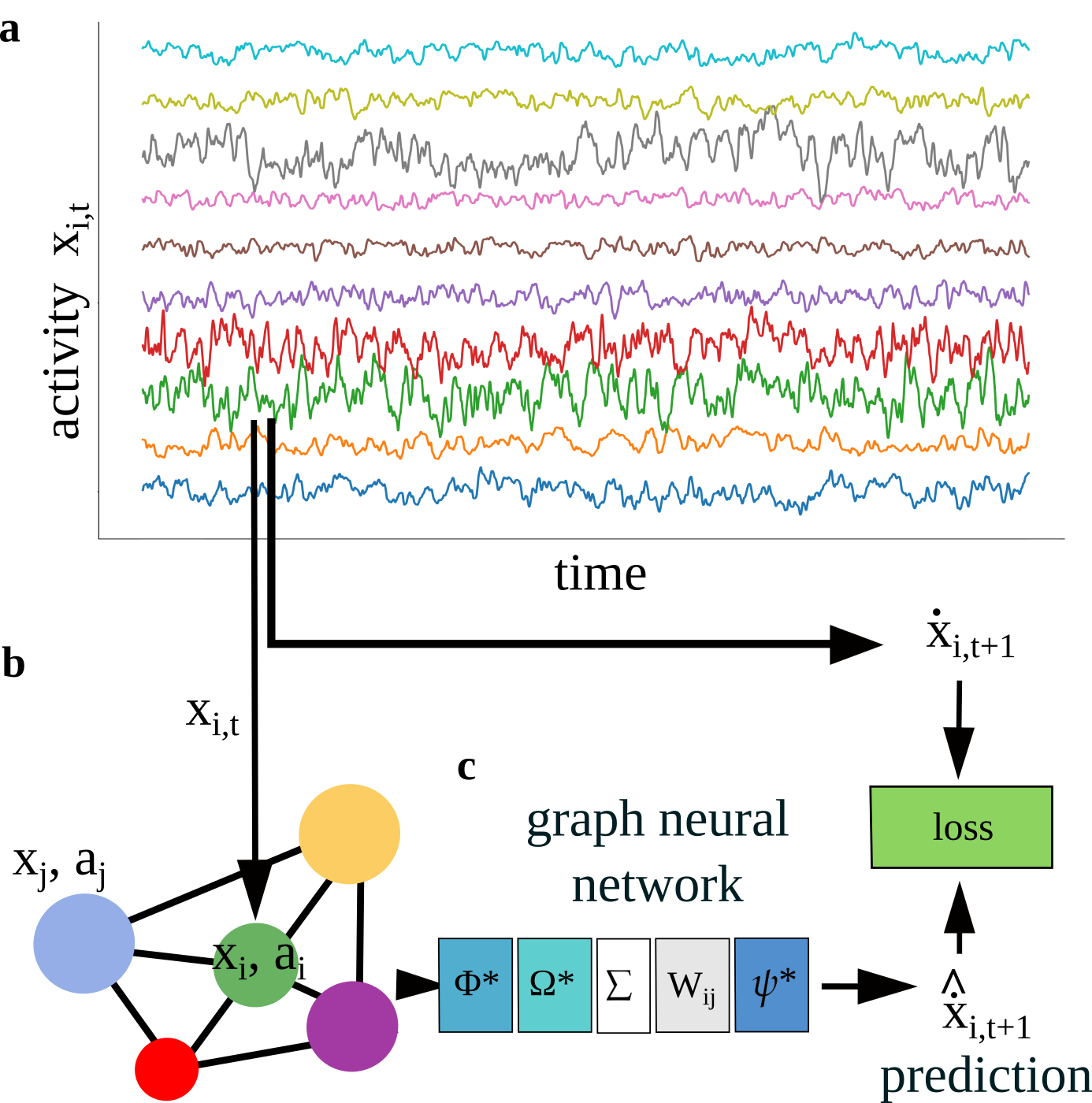

Graph Neural Networks: Mapping the Architecture of Connection

A Graph Neural Network (GNN) is utilized to model neural assemblies as graph structures, where individual neurons are represented as nodes and synaptic connections between them are defined as edges. This representation allows the GNN to directly process the connectivity patterns within the assembly. The Adjacency Matrix derived from the connectivity data serves as the primary input to the GNN, defining the graph’s topology. By treating the neural assembly as a graph, the GNN can leverage graph-based learning algorithms to analyze and infer properties of the network based on its structural organization, moving beyond traditional methods that treat neurons in isolation.

The Graph Neural Network (GNN) operates on the premise that network functionality is directly determined by its structural connectivity. Specifically, the GNN analyzes the Connectivity Matrix, which defines the synaptic relationships between neurons within a Neural Assembly, to predict intrinsic neuron properties. These predicted properties include Neuron Type – classifying neurons based on their physiological characteristics – and Update Rule, defining how a neuron’s state changes based on incoming signals. By processing the connectivity data, the GNN effectively infers the functional state of the network without requiring explicit knowledge of individual neuron parameters, offering a data-driven approach to neural modeling.

Employing a N-dimensional latent vector to represent individual neuron properties enables efficient capture of heterogeneity within a neural assembly. This approach moves beyond discrete classifications of neuron type and update rule, allowing for a continuous representation of characteristics. By encoding these properties as a vector, the model reduces the computational complexity associated with tracking individual parameters for each neuron, facilitating scalability to larger networks. The dimensionality N represents a trade-off between representational capacity and computational cost; higher values allow for more nuanced characterization but increase the parameter space, while lower values offer computational efficiency at the expense of detail. This vector-based representation is learned directly from the connectivity matrix, allowing the network to infer and represent inherent diversity without explicit labeling.

From Simulation to Inference: The Predictive Power of Network Reconstruction

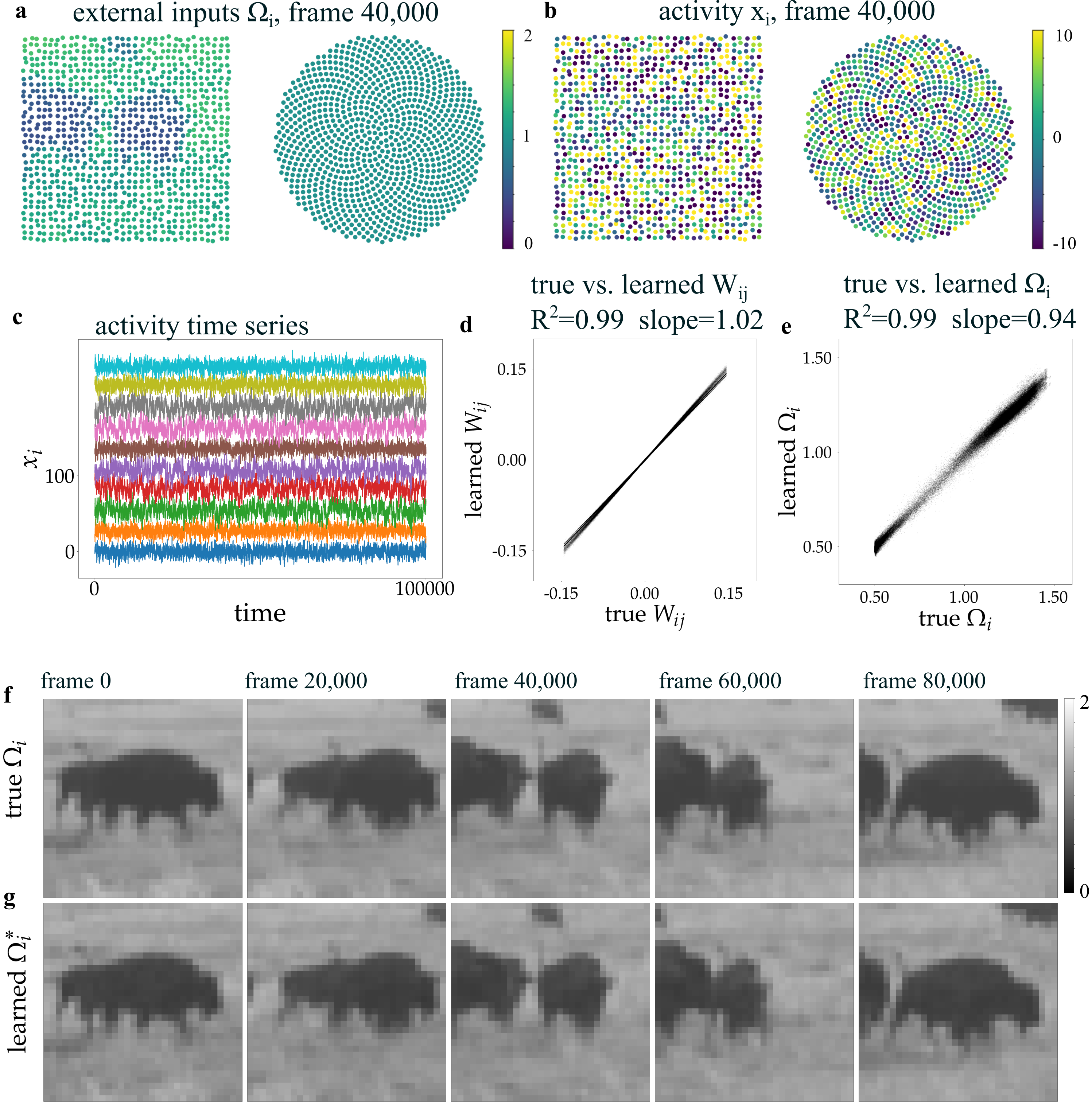

Simulation environments are utilized to generate a variety of input conditions for the neural assembly. These environments model realistic scenarios by defining parameters for diverse external stimuli, including variations in intensity, duration, and spatial distribution. This allows for systematic exploration of the neural assembly’s response to a wide range of potential inputs, effectively creating a controlled experimental setting within the computational model. The simulation process generates datasets of stimulus-response pairs which are then used to train and validate the Graph Neural Network (GNN) used for predictive inference.

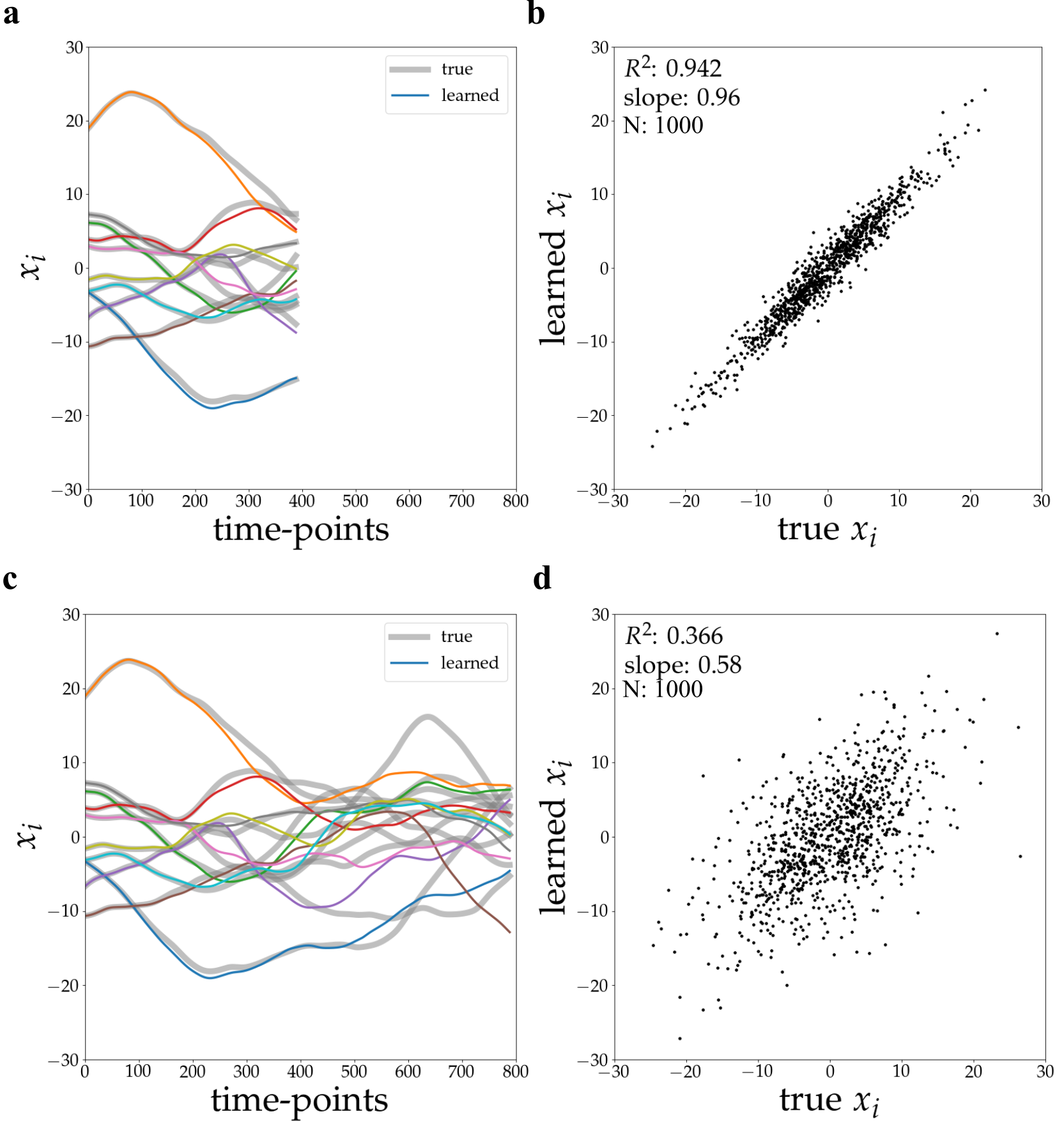

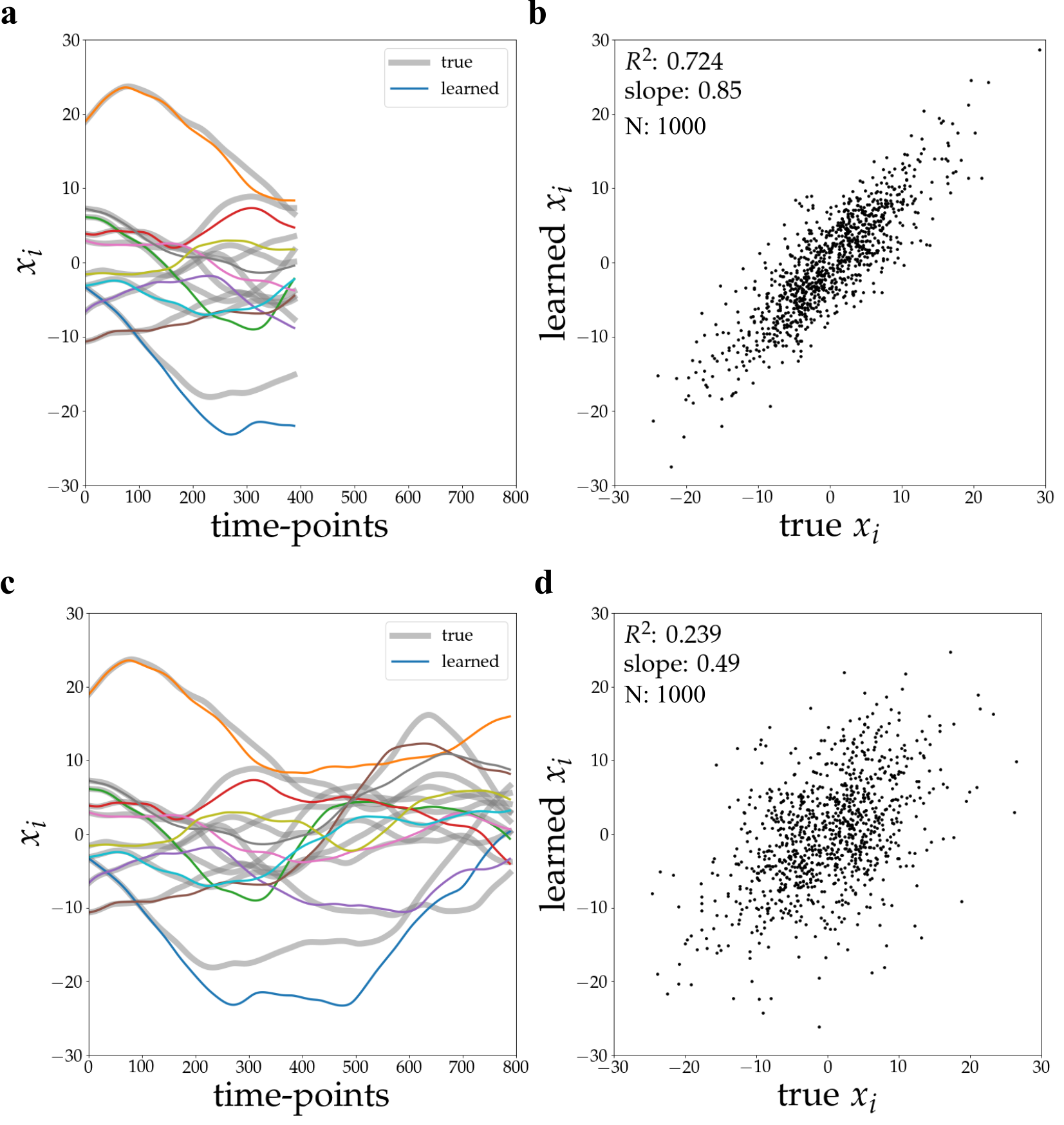

Rollout inference utilizes the trained Graph Neural Network (GNN) to forecast the temporal evolution of neural assembly activity. This predictive capability was evaluated by simulating network responses to various external stimuli and comparing the predicted activity with the actual simulated response. Quantitative analysis demonstrated a high degree of correlation, as evidenced by an R² value of 0.996 achieved over a prediction horizon of 800 time steps. This indicates the GNN effectively models the dynamic relationships within the neural assembly, enabling accurate forecasting of future states based on initial conditions and input stimuli.

Regularization techniques are integral to maximizing the predictive power of the trained Graph Neural Network (GNN). These methods, including L1 and L2 regularization as well as dropout, mitigate overfitting to the training data by penalizing model complexity. This penalty encourages the network to learn more robust and generalizable features, thereby improving its ability to accurately predict responses to novel, previously unseen external stimuli. The application of regularization results in a model that doesn’t simply memorize the training data, but instead learns underlying patterns, leading to enhanced performance and broader applicability across diverse input conditions.

Unveiling Causal Mechanisms: Towards a Deeper Understanding of Neural Systems

Investigating the dynamics of neural assemblies moves beyond simple correlation to establish causal relationships between synaptic connections and resulting network activity. This approach utilizes targeted perturbations within the modeled neural network, allowing researchers to directly assess how altering specific connections impacts overall assembly behavior. By systematically disrupting or strengthening individual synapses, it becomes possible to discern which connections are critical for specific functions, such as signal propagation or pattern completion. This capability provides a mechanistic understanding of how neural circuits operate, moving beyond descriptive models to reveal the underlying principles governing information processing within the brain. The identified causal links offer valuable insights into the potential roles of different connections in cognitive processes and neurological disorders, paving the way for more targeted interventions and therapies.

The research team advanced their computational framework by employing symbolic regression, a technique that uncovers underlying mathematical relationships within complex data. This approach moved beyond simply observing network dynamics to actively deriving analytical transfer functions – concise equations that describe how signals propagate through the neural assembly. Rather than relying on approximations, symbolic regression produced explicit formulas representing the network’s behavior, allowing for a deeper, more interpretable understanding of its computational properties. These derived functions, expressed mathematically, provide a precise characterization of stimulus-response relationships and open avenues for predicting network behavior under novel conditions, essentially translating learned dynamics into a readily usable, analytical form.

A novel approach utilizing a coordinate-based Multilayer Perceptron (MLP) demonstrates a remarkable capacity to model how spatial external stimuli impact neural network responses. This architecture effectively translates the location of incoming signals into alterations within the network’s activity, achieving complete accuracy in reconstructing the network’s connectivity matrix – as evidenced by a perfect R² value of 1.00. Furthermore, the MLP accurately classifies neuron types, again with 100% accuracy, suggesting a strong correlation between spatial input and the resulting neuronal organization and function. This precise mapping highlights the potential for understanding how external factors shape neural circuits and influence information processing within the brain, opening avenues for advanced computational neuroscience and potentially biomimetic engineering.

The study reveals a predictable pattern: systems, even those as complex as simulated neural assemblies, inevitably exhibit decay over time, though the manner of that decline can be surprisingly graceful. This echoes Bertrand Russell’s observation that, “The only thing that you see from being afraid is what you fear.” The research demonstrates how Graph Neural Networks can dissect the ‘fear’ – the underlying mechanisms – from observed activity, revealing latent connectivity and functional properties. While the networks don’t prevent decay, they offer insight into its progression, highlighting how even apparent stability may only represent a temporary delay of inevitable systemic change. The recovery of external stimuli through latent representations suggests a fleeting grasp of order before the entropic tide claims it.

What Lies Ahead?

The capacity to infer mechanistic underpinnings from observed dynamics, as demonstrated by this work, is not a triumph over complexity, but an acknowledgement of its inevitable decay. Every recovered connection, every predicted stimulus, is merely a snapshot of a system’s past – a fossil in the temporal strata of activity. The true challenge does not lie in reconstructing the network, but in predicting its future drift, its inevitable divergence from the recovered state. Technical debt, in this context, is not merely imperfect code, but the accumulating difference between model and reality.

Current limitations are not deficiencies, but opportunities. The reliance on simulated data, while providing a clean foundation, highlights the fragility of these methods when confronted with the noise inherent in biological systems. Future work must address the question of robustness – how gracefully does the inference degrade as the signal weakens and the chaos increases? The next iteration will likely involve exploring architectures capable of explicitly modeling uncertainty, recognizing that perfect reconstruction is a phantom goal.

Ultimately, the value of this approach will not be measured by its ability to mirror existing knowledge, but by its capacity to reveal novel dynamics. Each bug, each unexpected inference, is a moment of truth in the timeline – a signal that the model, and by extension, our understanding, is incomplete. The pursuit of mechanistic insight is, therefore, not a quest for static truth, but a continuous negotiation with the inherent impermanence of complex systems.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.13325.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Wuchang Fallen Feathers Save File Location on PC

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Brown Dust 2 Mirror Wars (PvP) Tier List – July 2025

- All weapons in Wuchang Fallen Feathers

- Where to Change Hair Color in Where Winds Meet

- Top 15 Celebrities in Music Videos

- Here Are the Best TV Shows to Stream this Weekend on Paramount+, Including ‘48 Hours’

- Best Video Games Based On Tabletop Games

- Macaulay Culkin Finally Returns as Kevin in ‘Home Alone’ Revival

2026-02-17 14:46