Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a method to dramatically speed up graph analysis by moving computations from discrete nodes to a continuous space, unlocking new possibilities for large-scale graph machine learning.

SWING efficiently approximates graph kernel methods using continuous-space random walks, improving computational efficiency for implicit graphs.

Calculating graph kernels on large, implicitly defined graphs presents a significant computational challenge due to the need for combinatorial calculations on potentially infinite node sets. This paper introduces ‘SWING: Unlocking Implicit Graph Representations for Graph Random Features’, a novel algorithm that bypasses direct graph traversal by performing random walks in the continuous embedding space of these graphs. SWING efficiently approximates graph kernel methods using a customized Gumbel-softmax sampling mechanism and linearized kernels, all without requiring explicit graph materialization. By leveraging the connection between implicit graphs and Fourier analysis, could SWING unlock new possibilities for scalable graph analysis in machine learning applications?

The Challenge of Quantifying Graph Similarity

A growing number of machine learning applications now represent data as graphs, reflecting complex relationships within domains like social networks, chemical compounds, and knowledge bases. Consequently, the ability to quantify the similarity between these graph-structured data points becomes crucial for tasks such as classification, clustering, and prediction. However, traditional methods for assessing graph similarity often face significant scalability issues when applied to large datasets. These techniques, frequently relying on exhaustive comparisons of graph features or substructures, exhibit computational complexity that increases rapidly with graph size, quickly becoming impractical for real-world applications involving thousands or even millions of nodes and edges. This limitation necessitates the development of novel approaches that can efficiently approximate graph similarity without sacrificing accuracy, enabling the broader application of powerful machine learning algorithms to complex, graph-based data.

The computational demands of determining similarity between graphs escalate dramatically as graph size increases, largely due to the challenges inherent in direct kernel calculations. These calculations, foundational to many powerful machine learning techniques – including support vector machines and Gaussian processes – require evaluating all pairwise comparisons between graph nodes or substructures. For graphs with even a modest number of nodes, this results in a computational complexity that quickly becomes prohibitive, scaling factorially or exponentially with graph size. Consequently, the application of sophisticated kernel methods, which excel at capturing complex relationships within data, is often impractical for large-scale graph datasets. This limitation necessitates the development of approximation techniques that can efficiently estimate kernel values without sacrificing crucial accuracy, a central focus within the field of graph machine learning.

A central difficulty in applying kernel methods to large graphs lies in the computational expense of accurately estimating graph kernels. These kernels, which quantify the similarity between graphs, often require comparing substructures or paths, leading to combinatorial explosion as graph size increases. Researchers are actively developing approximation techniques – including random feature maps and landmark-based methods – that aim to reduce this complexity without substantial loss of discriminatory power. The challenge isn’t simply computational speed; maintaining the kernel’s ability to distinguish between subtly different graph structures is paramount. Successful approximation strategies must balance efficiency with fidelity, enabling the application of powerful machine learning algorithms to increasingly large and complex graph datasets, and pushing the boundaries of what is computationally feasible in areas like drug discovery, social network analysis, and materials science.

Graph Random Features: A Pathway to Computational Efficiency

Graph Random Features address computational bottlenecks in kernel methods by transforming the kernel matrix – typically dense and requiring O(n^2) storage and O(n^3) computation for operations like matrix inversion – into a sparse representation. This decomposition is achieved by mapping each node in the graph to a lower-dimensional vector space using randomly selected features. The resulting kernel approximation then relies on computations involving these lower-dimensional vectors, reducing both memory requirements and computational complexity. Specifically, the computational cost associated with kernel operations can be reduced to approximately O(n \cdot m), where ‘n’ is the number of nodes and ‘m’ is the number of random features, provided ‘m’ is significantly smaller than ‘n’. This sparsity enables the application of kernel methods to graphs with a larger number of nodes than would be feasible with traditional kernel matrix calculations.

Kernel methods, while powerful, scale poorly with graph size due to the O(n^3) complexity of computing and inverting the kernel matrix for a graph with n nodes. Graph Random Features address this limitation by approximating the kernel matrix using a set of randomly selected features. This approximation reduces the computational complexity to approximately O(n \cdot m), where m is the number of random features and m < n. Importantly, the number of random features m can be tuned to control the trade-off between approximation accuracy and computational efficiency. Empirical results demonstrate that, with appropriate selection of m, Graph Random Features can achieve comparable performance to exact kernel methods on various graph tasks while enabling scalability to graphs with millions of nodes.

The performance of Graph Random Features is directly impacted by the fidelity of the kernel approximation and the selection of random features. A higher-quality approximation – minimizing the difference between the full kernel matrix and its sparse representation – generally leads to improved accuracy in downstream tasks. The choice of random features, specifically their number and the function used to generate them, influences both the approximation quality and computational cost; increasing the number of features improves accuracy but also increases the dimensionality of the approximated feature space and associated computational demands. Therefore, a trade-off exists between approximation accuracy and computational efficiency, necessitating careful consideration of these parameters during implementation.

SWING: Introducing Continuous Random Walks for Kernel Approximation

Traditional graph kernel methods approximate similarity by counting walks between nodes in a discrete graph. SWING departs from this approach by formulating random walks in a continuous space embedding of the graph. This is achieved by representing graph structure with node positions in a continuous space and defining transition probabilities based on distances between these positions. Instead of discrete steps between nodes, SWING simulates walks as continuous trajectories, allowing for differentiation and enabling the use of gradient-based optimization techniques. This continuous representation facilitates kernel approximation without the limitations imposed by discrete walk enumeration, and allows for more efficient computation of kernel matrices, particularly for large graphs.

SWING utilizes the Matrix Exponential and Gumbel-Softmax to facilitate continuous random walks suitable for kernel approximation. The Matrix Exponential exp(A), where A is an adjacency matrix, allows for the propagation of information across continuous space, effectively smoothing the graph structure. Gumbel-Softmax, a differentiable approximation of the argmax function, is employed to sample continuous walk directions, enabling gradient-based optimization of walk parameters. This combination allows for the computation of approximate kernel values while maintaining differentiability, which is crucial for end-to-end training of models utilizing the kernel. The Gumbel-Softmax reparameterization trick ensures that the sampling process is differentiable, enabling gradients to flow through the random walk process.

Importance Sampling within the SWING framework addresses the computational challenges inherent in random walk-based kernel methods by selectively weighting paths based on their contribution to the kernel estimate. This technique avoids uniformly sampling all possible walks, instead prioritizing those with higher probabilities of significantly impacting the final kernel value. Specifically, SWING utilizes Importance Sampling to re-weight the paths generated by the continuous random walks, effectively concentrating computational resources on the most informative trajectories and diminishing the contribution of less relevant ones. This focused approach dramatically improves the efficiency of kernel approximation, enabling the computation of kernel values with a reduced variance and lower computational cost compared to standard Monte Carlo methods, particularly for large graphs where exhaustive path exploration is impractical.

Validating SWING: Demonstrating Accuracy and Efficiency

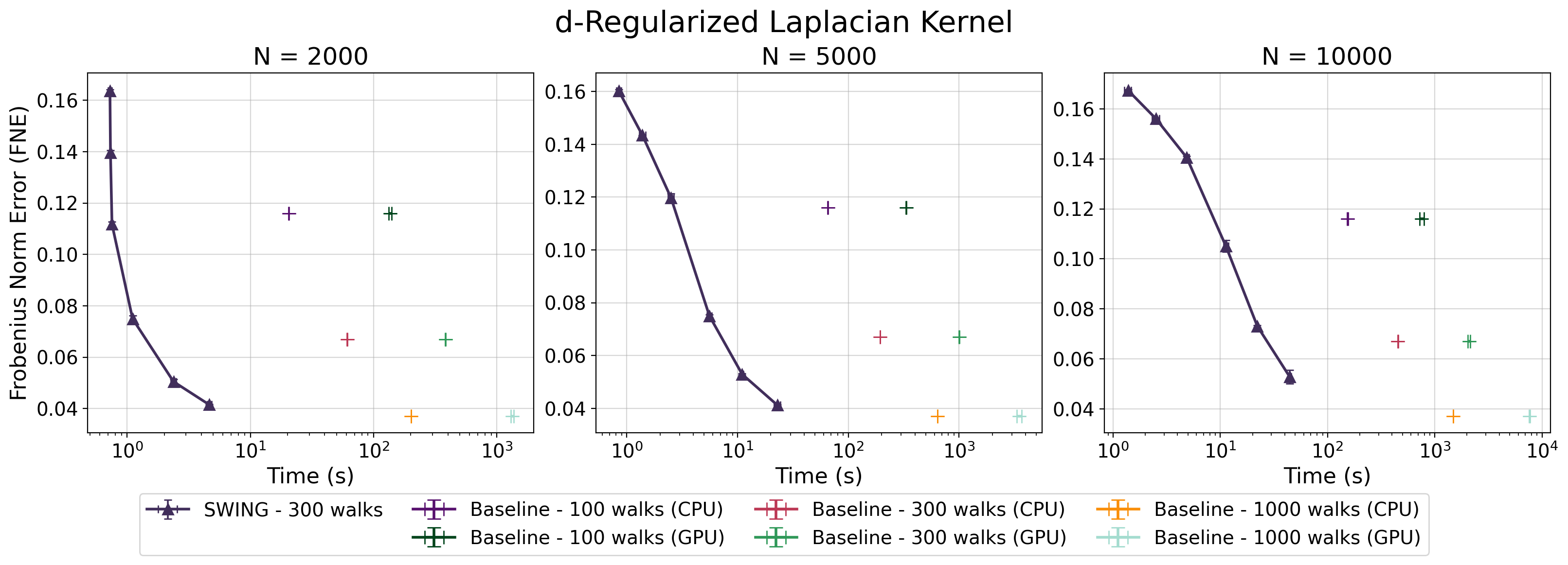

The fidelity of SWING’s kernel approximation is established through a rigorous evaluation using the Frobenius Norm Error, a metric that quantifies the difference between the approximated kernel matrix and the true kernel matrix. This approach provides a precise and quantifiable assessment of performance, allowing for a detailed understanding of the approximation’s accuracy across various datasets and kernel parameters. Specifically, the Frobenius Norm Error calculates the square root of the sum of the squares of the differences between corresponding elements in the two matrices – a value that directly reflects the overall error in the kernel approximation. Lower Frobenius Norm Error values indicate higher accuracy, demonstrating SWING’s ability to reliably estimate kernel functions without significant loss of information – a critical factor for the overall performance of Gaussian Random Field applications.

Rigorous testing confirms that SWING delivers accuracy on par with established Gaussian Random Field (GRF) methods when applied to synthetic point cloud data. Evaluations encompassed a diverse range of commonly used kernels – including pp-step random walk, diffusion, and regularized Laplacian – ensuring broad applicability of the findings. This consistent performance across different kernel types suggests SWING effectively captures the underlying geometric properties of the data, offering a reliable alternative to traditional GRF approaches without sacrificing fidelity. The ability to maintain comparable accuracy while offering substantial speed improvements positions SWING as a compelling tool for applications requiring both precision and efficiency in point cloud processing.

Investigations reveal that SWING significantly accelerates Gaussian Random Field (GRF) computations, achieving up to a tenfold increase in inference speed when contrasted with conventional GRF methodologies. This performance boost is attained without compromising accuracy, as demonstrated through rigorous evaluation using established metrics. Notably, SWING’s efficiency extends to kernel construction itself; as the complexity of the underlying mesh increases – representing larger and more detailed datasets – SWING consistently outperforms standard methods in building the kernel, thereby providing a scalable solution for high-resolution geometric processing and analysis. This combination of speed and maintained precision positions SWING as a compelling alternative for applications requiring rapid and accurate GRF-based calculations.

Expanding Horizons: Implicit Graphs and Future Directions

The versatility of SWING extends beyond traditional graphs to encompass implicit graphs, a crucial advancement for analyzing data where relationships aren’t explicitly stated but emerge from observations. In these scenarios, edges aren’t pre-defined; instead, they are dynamically inferred from the data itself, such as similarity metrics between data points or probabilistic relationships. This capability dramatically broadens SWING’s applicability, enabling its use in fields like recommendation systems, where user-item interactions define the graph, and social network analysis, where connections arise from behavioral patterns. By operating effectively on these implicitly defined structures, SWING unlocks insights from datasets where traditional graph algorithms would be ineffective or require substantial pre-processing, paving the way for more nuanced and data-driven analyses across diverse domains.

Spectral graph analysis, a powerful technique for understanding graph structure, often relies on computationally expensive kernels like the Diffusion and Regularized Laplacian. Recent advancements demonstrate that SWING – a method for efficiently computing graph kernels – provides accurate approximations of these kernels, drastically reducing computational complexity. This efficiency unlocks new possibilities for analyzing large-scale graphs, previously intractable due to kernel computation bottlenecks. By enabling faster computation of \textbf{A}x – where \textbf{A} represents the graph adjacency matrix and x is a vector of node features – SWING facilitates more nuanced spectral embeddings and allows researchers to explore deeper relationships within complex network data, potentially revolutionizing fields reliant on graph-based modeling.

Continued development centers on enhancing SWING’s computational efficiency, particularly for exceptionally large and complex graphs, through algorithmic refinements and parallelization strategies. Simultaneously, research is actively investigating SWING’s potential to improve the performance of graph neural networks by providing a more robust and scalable means of computing graph signals. The technique also shows promise in bioinformatics, where it could facilitate analyses of protein-protein interaction networks and genomic data, potentially revealing new insights into disease mechanisms and therapeutic targets. This expansion into these diverse fields aims to establish SWING as a versatile tool for tackling a broad spectrum of challenges within graph-structured data analysis.

The pursuit of computational efficiency, as demonstrated by SWING, echoes a fundamental tenet of mathematical elegance. This work, by approximating graph kernels through continuous space random walks, prioritizes scalability without sacrificing accuracy-a principle akin to seeking the most concise and provable solution. As Paul Erdős famously stated, “A mathematician knows a great deal of things, and those things are very useful – but not many.” The utility of SWING lies not simply in its performance gains for implicit graphs, but in its elegant reformulation of kernel methods, offering a path toward truly scalable graph machine learning. The algorithm’s emphasis on asymptotic behavior-reducing complexity through intelligent approximation-aligns perfectly with a mathematician’s ideal of finding the most essential and generalizable truth.

What Lies Ahead?

The introduction of SWING represents a step, albeit a necessary one, towards taming the inherent computational beast of graph kernels. The algorithm’s reliance on continuous space random walks is a clever maneuver, circumventing the combinatorial explosion that plagues many graph methods. However, the elegance of the approach should not obscure the fact that approximation is still at play. The question remains: how tightly can this approximation bound be established, and what classes of implicit graphs will consistently benefit without unacceptable fidelity loss? If it feels like magic, one hasn’t revealed the invariant.

Future work should address the sensitivity of SWING to parameter selection – the dimensionality of the embedding space, the length of the random walks, and the kernel bandwidth. A rigorous theoretical analysis, beyond empirical demonstration, is required to understand the interplay of these parameters and their impact on generalization performance. Furthermore, extending SWING to handle dynamic graphs, where edges and nodes change over time, presents a significant challenge.

Ultimately, the true measure of SWING’s success will not be its speed on benchmark datasets, but its ability to unlock insights from truly massive, unstructured graph data – the kind that currently resides beyond the reach of most kernel methods. The pursuit of provable guarantees, rather than merely scalable heuristics, remains the paramount objective.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.12703.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Wuchang Fallen Feathers Save File Location on PC

- Where to Change Hair Color in Where Winds Meet

- Brown Dust 2 Mirror Wars (PvP) Tier List – July 2025

- All weapons in Wuchang Fallen Feathers

- Top 15 Celebrities in Music Videos

- Here Are the Best TV Shows to Stream this Weekend on Paramount+, Including ‘48 Hours’

- Macaulay Culkin Finally Returns as Kevin in ‘Home Alone’ Revival

- HSR 3.7 breaks Hidden Passages, so here’s a workaround

2026-02-17 03:01