Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers are exploring how advanced artificial intelligence can be trained to detect early indicators of Alzheimer’s Disease through language analysis.

This review examines the efficacy of fine-tuning large language models with supervised learning, representation probing, and novel data synthesis techniques for Alzheimer’s Disease detection.

Early and reliable detection of Alzheimer’s disease remains a significant clinical challenge, often hindered by limited labeled datasets. The study ‘What Do LLMs Know About Alzheimer’s Disease? Fine-Tuning, Probing, and Data Synthesis for AD Detection’ investigates the potential of large language models (LLMs) to address this issue through supervised fine-tuning and representation learning. Researchers demonstrate that fine-tuning enhances LLM performance, revealing task-relevant information encoded within internal representations and enabling a novel data synthesis method utilizing linguistic markers to generate diagnostically informative samples. Could this approach unlock new avenues for LLMs in biomedical applications and ultimately improve early detection rates for neurodegenerative diseases?

The Ghosts in the Machine: Detecting Early Linguistic Drift

Alzheimer’s Disease poses a growing global health crisis, impacting millions and placing immense strain on healthcare systems and families. The insidious nature of the disease-its slow, progressive deterioration of cognitive function-demands a proactive approach to detection, moving beyond reliance on symptoms that manifest only after substantial neurological damage has occurred. Current diagnostic methods, frequently involving subjective evaluations and neuroimaging, can be costly, time-consuming, and inaccessible to many. Consequently, there is a pressing need for innovative, scalable, and accurate methods to identify individuals in the earliest stages of AD, ideally before irreversible brain changes take hold, offering a critical opportunity to intervene with potential disease-modifying therapies and improve patient outcomes. This pursuit of early detection isn’t simply about diagnosis; it’s about preserving quality of life and alleviating the immense personal and societal burdens associated with this devastating condition.

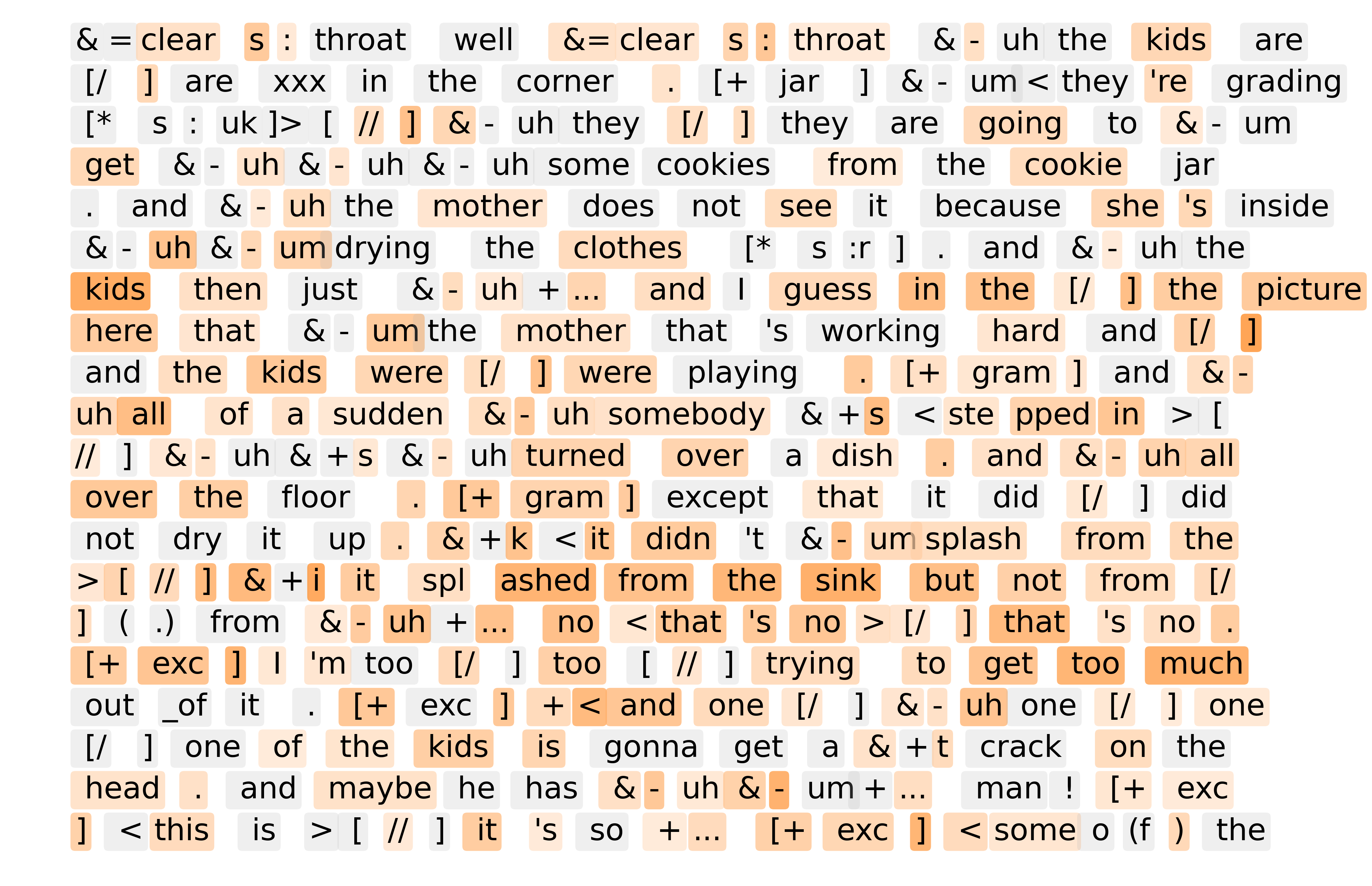

The earliest stages of cognitive decline, even before noticeable memory loss or confusion, frequently manifest as subtle shifts in an individual’s language use. Research indicates that increased hesitations – the ‘umms’ and ‘ahs’ that pepper speech – and a tendency toward repetition of words or phrases can serve as surprisingly sensitive indicators of underlying neurological changes. These linguistic markers aren’t necessarily signs of reduced vocabulary or grammatical skill; rather, they suggest the brain is working harder to retrieve information and formulate thoughts, a struggle often preceding the full emergence of clinical symptoms. This phenomenon offers a valuable diagnostic window, as tracking these minute linguistic shifts through speech analysis may allow for earlier detection of conditions like Alzheimer’s Disease, potentially enabling timely interventions and improved patient outcomes before significant cognitive impairment takes hold.

Current methods for gauging cognitive function frequently rely on assessments vulnerable to interpretation, demanding significant clinician time and potentially introducing variability in diagnosis. These traditional evaluations, while valuable, can be influenced by factors like a patient’s mood, education level, or even the examiner’s own biases, complicating early detection of neurodegenerative diseases. Consequently, researchers are increasingly focused on developing automated analyses of language – a readily available and often subtly altered biomarker – using computational linguistics and machine learning. This data-driven approach promises to provide objective, repeatable measurements of linguistic features, offering a potentially more sensitive and efficient means of identifying individuals at risk of cognitive decline before symptoms become clinically apparent.

Teaching Old Models New Tricks: LLM Fine-tuning for AD

Large Language Model (LLM) fine-tuning was implemented to specialize general-purpose LLMs for the detection of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). This process involves further training a pre-trained LLM on a dataset containing language patterns characteristic of individuals with AD, allowing the model to discern subtle linguistic differences indicative of cognitive decline. By adjusting the model’s weights based on this AD-specific data, the LLM’s ability to recognize and interpret language associated with the disease is significantly improved, moving beyond general language understanding to a focused understanding of AD-related communication patterns. This adaptation is crucial, as individuals with AD often exhibit distinct changes in vocabulary, sentence structure, and semantic coherence, requiring a specialized model for accurate detection.

Supervised Fine-tuning (SFT) was implemented as the primary adaptation method for large language models, leveraging the publicly available DementiaBank dataset. This dataset provides labeled transcripts of communicative interactions, specifically designed for the study of language in individuals with and without cognitive impairment. The SFT process involved presenting the LLMs with these labeled examples – consisting of text inputs and corresponding diagnostic labels – and iteratively adjusting the model’s parameters to minimize the difference between predicted and actual labels. This approach enabled the models to learn the specific linguistic features and patterns associated with Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) as represented within the DementiaBank corpus, effectively tailoring their capabilities for AD detection tasks.

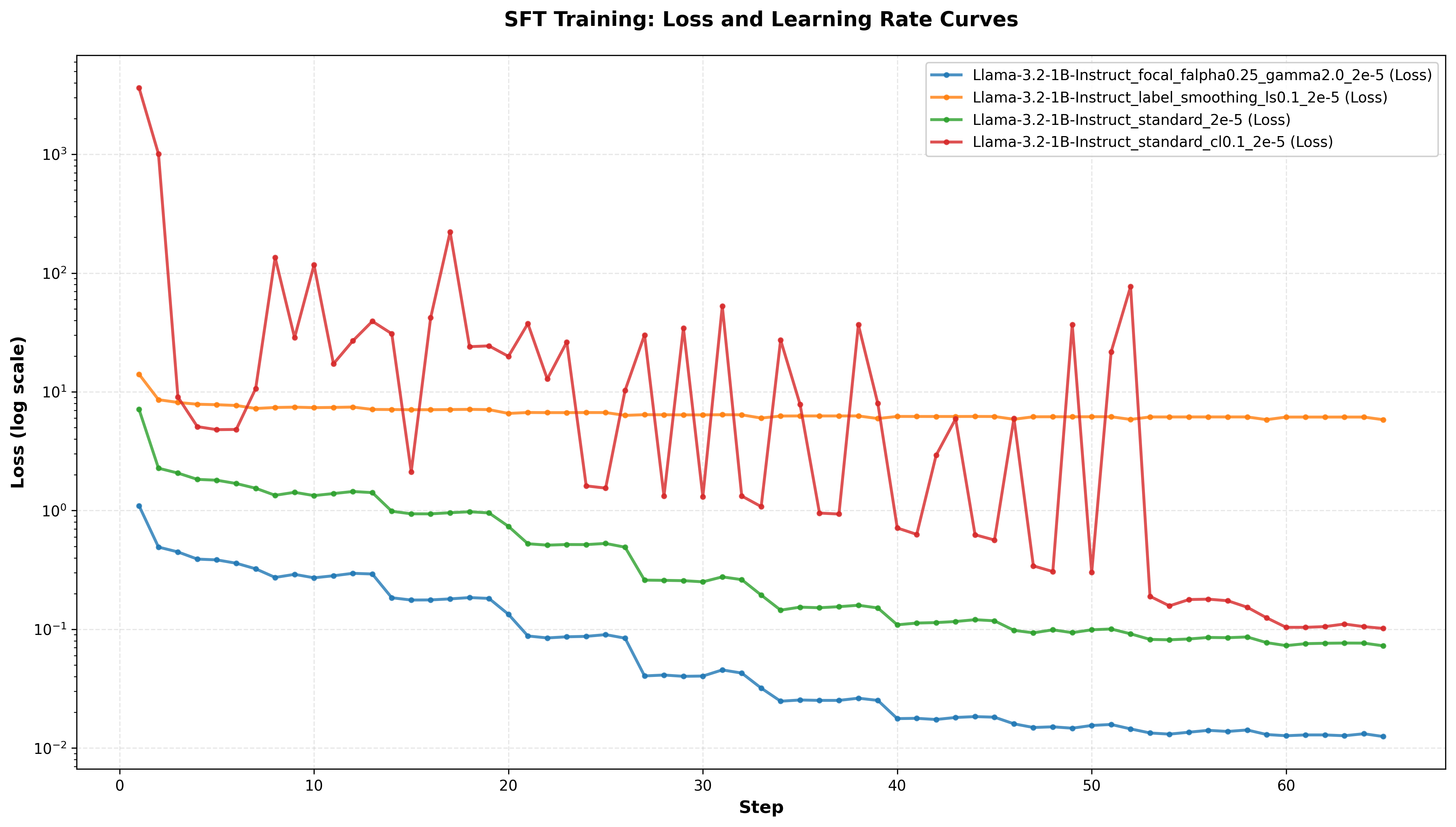

To improve the performance and resilience of supervised fine-tuning (SFT) for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) detection, several advanced learning techniques were incorporated. Contrastive Learning was used to emphasize distinguishing features within the DementiaBank dataset, while Focal Loss addressed class imbalance by down-weighting easily classified examples and focusing on harder cases. Label Smoothing regularized the model by preventing overconfidence in predictions. The combined implementation of these techniques resulted in a peak accuracy of 0.868 on the test dataset, demonstrating enhanced model generalization and reliability in identifying AD-related language patterns.

Experimentation utilized LLama3-1b-instruct and Qwen-2.5-1.5b-instruct as base models for Supervised Fine-Tuning (SFT). Implementation of Label Smoothing loss during the SFT process resulted in a recorded accuracy of 0.853, an F1-Score of 0.919, and a Recall of 0.975. These metrics demonstrate the effectiveness of Label Smoothing in enhancing model performance on the AD detection task when applied to these specific foundational models.

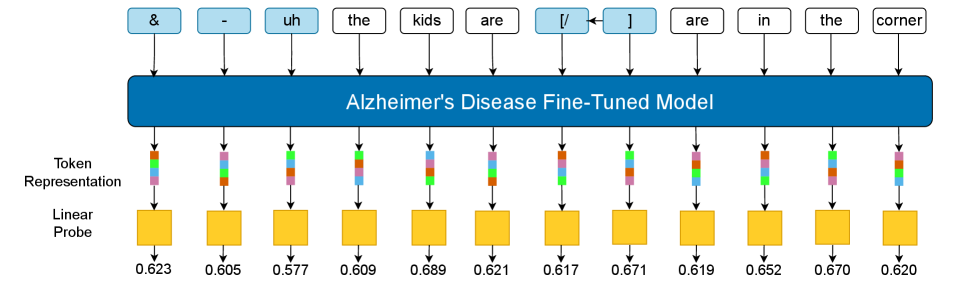

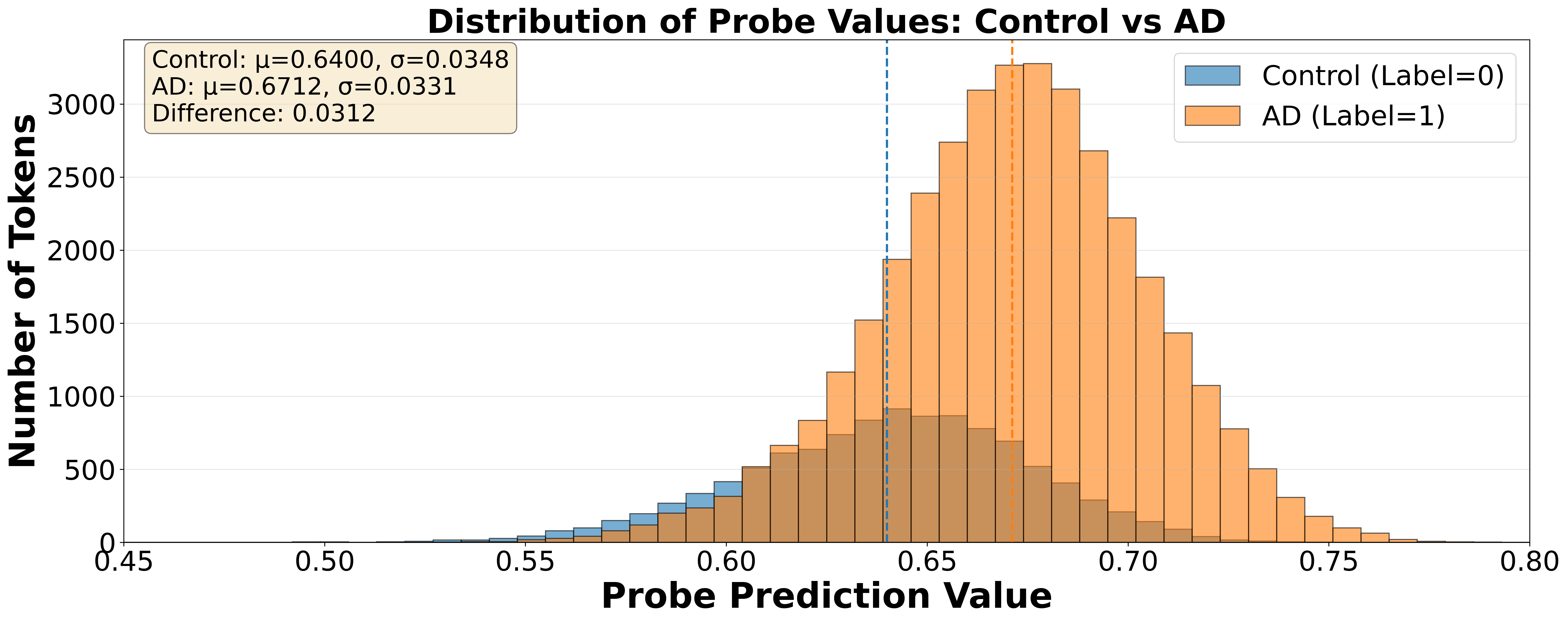

Peeking Inside the Black Box: Probing Model Representations

Linear probes were utilized as a method for interpreting the internal representations learned by the fine-tuned Large Language Models (LLMs). These probes consist of simple linear classifiers trained to predict diagnostic status – Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) versus healthy control – from the LLM’s hidden state vectors. By training a linear model on top of the frozen LLM representations, researchers can quantify the degree to which information relevant to AD diagnosis is encoded within those representations. The performance of the linear probe serves as a proxy for the interpretability of the LLM; higher accuracy indicates a more readily accessible and discernible signal related to the target diagnostic task. This approach avoids modifying the LLM itself, preserving its learned knowledge while enabling focused analysis of its representational space.

Token-level representation analysis involved examining the internal activations of the fine-tuned Large Language Models (LLMs) for individual tokens within patient transcripts. This process identified specific tokens-words or sub-word units-that exhibited statistically significant differences in their representation between Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) patients and healthy control subjects. Feature importance scores were calculated to quantify the contribution of each token to the classification task, allowing researchers to isolate those most indicative of cognitive impairment. Tokens associated with linguistic features known to be affected by AD, such as function words, pronoun usage, and semantic complexity, consistently demonstrated higher importance scores, confirming their diagnostic value within the model’s learned representations.

Following the identification of specific linguistic markers differentiating Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) patients from healthy controls via linear probe analysis, a data synthesis strategy was implemented to generate artificial transcripts. This process aimed to augment existing datasets with examples exhibiting these identified markers, thereby improving model robustness and diagnostic accuracy. Synthetic transcripts were created to statistically match the observed distributions of these features in genuine AD and control samples, allowing for controlled experimentation and the mitigation of data scarcity issues. The generated data was not intended to replicate natural language perfectly, but rather to specifically embody the linguistic characteristics demonstrably associated with cognitive decline as revealed by the representation analysis.

The T5 model was utilized as a text-to-text generator to create synthetic speech transcripts exhibiting linguistic characteristics identified as diagnostic signals for Alzheimer’s Disease (AD). This process involved inputting plain text prompts into the T5 model and conditioning its output to specifically include features – such as increased semantic errors, simplified sentence structures, and repetitive phrasing – that were previously determined to differentiate AD patients from healthy controls via linear probe analysis of LLM representations. The T5 model’s generative capabilities allowed for the controlled introduction of these features, effectively augmenting the dataset with synthetic examples that mimic the linguistic patterns associated with cognitive decline.

Beyond Detection: Implications for Early Intervention and Future Research

Recent advancements showcase the viability of automated Alzheimer’s disease (AD) detection through the innovative application of large language model (LLM) fine-tuning and representational analysis. By adapting powerful LLMs – initially designed for natural language processing – researchers have demonstrated the ability to discern subtle linguistic patterns indicative of cognitive decline. This process involves training the LLM on speech or text samples and then analyzing the resulting internal representations to identify biomarkers associated with AD. The success of this approach signifies a shift towards data-driven diagnostics, potentially offering a scalable and objective method for early detection that complements traditional clinical assessments. This technology could one day provide a more accessible and efficient pathway for identifying individuals at risk, fostering proactive healthcare and personalized interventions.

The prospect of earlier Alzheimer’s disease detection, as demonstrated by recent advances in natural language processing, holds significant promise for altering the trajectory of the illness. Timely interventions, initiated before substantial neurodegeneration occurs, may slow cognitive decline and preserve functional abilities. These interventions range from lifestyle modifications-such as increased physical exercise and cognitive training-to emerging pharmacological therapies currently under investigation. By identifying individuals at risk earlier in the disease process, clinicians can implement personalized treatment plans and provide supportive care, ultimately aiming to improve patient quality of life and potentially delay the onset of severe symptoms. The ability to detect subtle linguistic changes indicative of early cognitive impairment offers a non-invasive and scalable approach to screening, potentially leading to more effective disease management and improved patient outcomes.

A significant outcome of this research is the creation of a synthetically generated dataset mimicking the linguistic patterns associated with Alzheimer’s disease. This resource addresses a critical limitation in the field – the scarcity of labeled data for training robust detection models. By offering a readily available, expanded dataset, researchers can now develop and rigorously evaluate algorithms without being constrained by the challenges of acquiring and annotating real-world patient data. This synthetic data isn’t intended to replace clinical datasets, but rather to augment them, enabling more comprehensive model training and facilitating the exploration of novel approaches to early Alzheimer’s diagnosis. The accessibility of this resource promises to accelerate progress in the field and foster the creation of more accurate and reliable diagnostic tools.

Continued investigation must prioritize assessing whether these findings extend beyond the studied demographics, acknowledging that Alzheimer’s disease manifests differently across ethnic, cultural, and linguistic backgrounds. A crucial next step involves combining these linguistic biomarkers – subtle patterns in speech and writing – with established clinical data, such as neuroimaging results, cerebrospinal fluid analyses, and genetic predispositions. This multi-faceted approach promises a more holistic and accurate diagnostic picture, potentially revealing earlier and more reliable indicators of cognitive decline than any single method could achieve alone, and ultimately paving the way for personalized interventions tailored to individual patient profiles.

The pursuit of representing complex conditions like Alzheimer’s Disease within a Large Language Model feels…familiar. It’s another layer of abstraction built upon existing, imperfect data. The researchers demonstrate gains through fine-tuning and data synthesis, but one suspects even the most elegant representation is merely a sophisticated approximation. As Claude Shannon observed, “The most important thing is to get the message across.” This work attempts to encode a ‘message’ – the subtle linguistic markers of cognitive decline – but the channel, the model itself, introduces noise. It’s a useful signal, certainly, but production – the messy reality of clinical application – will undoubtedly reveal the limitations of even the most meticulously crafted representation. It’s not about perfect knowledge; it’s about managing the inevitable degradation of information.

What’s Next?

The pursuit of algorithmic diagnosis, in this case for Alzheimer’s Disease, invariably reveals the brittleness of ‘understanding’. This work demonstrates incremental gains in LLM performance, achieved through the familiar choreography of fine-tuning and data augmentation. But the boosted metrics obscure a fundamental question: are these models learning to detect Alzheimer’s, or simply to correlate linguistic patterns with diagnostic labels? The bug tracker, inevitably, will tell the tale. The synthesized data, built on linguistic markers, feels less like a breakthrough and more like a sophisticated form of feature engineering-a temporary reprieve from the need for true semantic comprehension.

Future iterations will undoubtedly explore larger models and more elaborate data pipelines. Yet, the real challenge isn’t scale, but generalization. These systems excel within the carefully curated confines of research datasets. Production, as always, will introduce noise, ambiguity, and the frustrating reality that human language is rarely neat. The inevitable drift in performance will necessitate continuous retraining, a Sisyphean task disguised as ‘model maintenance’.

The promise of early detection remains potent, but this work underscores a crucial point: the models don’t deploy-they let go. The burden of validation, of ensuring clinical relevance, falls squarely on those who must interpret the outputs, manage the false positives, and navigate the ethical complexities of algorithmic medicine.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.11177.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- 20 Films Where the Opening Credits Play Over a Single Continuous Shot

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 50 Serial Killer Movies That Will Keep You Up All Night

- Here Are the Best TV Shows to Stream this Weekend on Paramount+, Including ‘48 Hours’

- ‘The Substance’ Is HBO Max’s Most-Watched Movie of the Week: Here Are the Remaining Top 10 Movies

- 17 Black Voice Actors Who Saved Games With One Line Delivery

- Top gainers and losers

- 20 Movies to Watch When You’re Drunk

- 10 Underrated Films by Ben Mendelsohn You Must See

2026-02-14 10:58