It was, perhaps, a touch optimistic to suggest that Netflix and Oracle would, by 2030, join the rather exclusive club of companies boasting a market capitalization exceeding a trillion dollars. One recalls a similar enthusiasm surrounding the South Sea Bubble, though admittedly, the streaming services offer slightly more tangible returns. As of this writing, however, both appear to be navigating waters considerably choppier than anticipated. Netflix, down a regrettable 38.6% from its recent peak, and Oracle, suffering an even more precipitous decline of 56.5%, present a picture of decidedly diminished prospects.

Currently, Netflix languishes at a mere $346.9 billion, while Oracle trails at $410.4 billion – a considerable distance from the company of Nvidia, Alphabet, Apple, Microsoft, Amazon, Broadcom, Meta Platforms, Tesla, Berkshire Hathaway, and even, rather surprisingly, Walmart. One begins to suspect that the pursuit of such astronomical valuations is, at best, a fool’s errand, and at worst, a symptom of a wider, and rather worrying, detachment from reality.

The question, naturally, is why. And whether a purchase might still be considered, despite the circumstances.

Oracle: A Spending Spree of Dubious Wisdom

Oracle, like many of its peers, is currently embroiled in the frantic, and largely unexamined, rush to embrace Artificial Intelligence. The notion that this technology will fundamentally alter the landscape of software-as-a-service is, of course, widely accepted. What is less clear is whether the expenditure required to achieve this transformation is, in any way, justified. Oracle’s investments are primarily focused on expanding its data centers for Oracle Cloud Infrastructure (OCI), and attempting to integrate its database services into the cloud offerings of Amazon, Microsoft, and Alphabet. A rather ambitious undertaking, one might observe.

The market, quite rightly, is beginning to exhibit a degree of skepticism regarding such capital-intensive ventures. Especially given Oracle’s reliance on a handful of large clients to generate sufficient order volume. A precarious position, to say the least.

As of the most recent quarterly report, Oracle carries approximately $99.98 billion in long-term debt, offset by a paltry $19.24 billion in cash. A balance sheet that would give even the most seasoned accountant cause for concern.

On February 1st, the company announced plans to raise between $45 and $50 billion in 2026 to fund this expansion, and to satisfy the demands of clients such as OpenAI, Nvidia, Advanced Micro Devices, Meta Platforms, TikTok, and xAI. The proposed methods – selling equity, convertible securities, and bonds – are all, shall we say, less than ideal. The interest rates on the bonds will be unfavorable, and Oracle’s stock price is hardly buoyant. A rather desperate measure, one suspects.

While debt is not inherently problematic, it requires sufficient cash flow to service. Oracle, however, reported a negative free cash flow of $13.2 billion in the second quarter of fiscal 2026, compared to $9.5 billion in the same period last year. The company has transitioned from a reliable cash cow to a capital-intensive money pit. Investors, understandably, are concerned.

There is a glimmer of hope, of course. Expenditure should eventually decline as capital expenditures decrease and revenue from the backlog materializes. But Oracle remains vulnerable to any slowdown in AI spending. A distinct possibility, given the prevailing economic climate.

If Oracle manages to achieve its forecast of $144 billion in OCI revenue by 2031, the company’s valuation could, conceivably, exceed a trillion dollars. But that remains a rather large ‘if’. And a continued failure to address its balance sheet could result in a prolonged period of underperformance.

Netflix: Valuation and the Warner Bros. Discovery Gambit

Unlike Oracle, which faces genuine structural challenges, Netflix’s recent decline is largely attributable to valuation concerns and the mixed reception surrounding its proposed acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery. One suspects the market has simply grown tired of paying a premium for a streaming service, however successful.

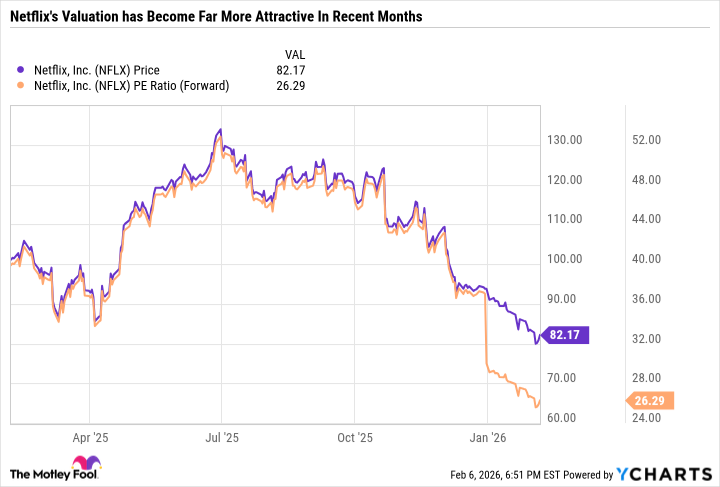

As the following chart illustrates, Netflix’s valuation has fallen considerably since its peak on June 30, 2025.

Currently trading at 26.3 times forward earnings, Netflix is approaching the S&P 500’s forward P/E ratio of 23.6. Though it remains, undeniably, a far superior company to the average S&P 500 constituent.

Netflix generates high margins and enjoys a solid growth rate. Its cash flow allows it to fund content spending without resorting to debt, providing a clear path for compounding over time. A rare and admirable quality in the current climate.

The company has achieved considerable success with both live-action and animated series and films, from Stranger Things to its most popular film, KPop Demon Hunters. A testament to its content creation capabilities.

The acquisition of Warner Bros. Discovery would broaden Netflix’s content suite and allow it to offer a combined subscription with HBO and HBO Max. A potentially lucrative combination, though hardly essential to the company’s success.

While a smart acquisition, Netflix does not need Warner Bros. Discovery to succeed. Which is why the stock remains a buy, even if the deal falls through. A comforting thought, in these uncertain times.

Read More

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Monster Hunter Stories 3: Twisted Reflection launches on March 13, 2026 for PS5, Xbox Series, Switch 2, and PC

- Here Are the Best TV Shows to Stream this Weekend on Paramount+, Including ‘48 Hours’

- 🚨 Kiyosaki’s Doomsday Dance: Bitcoin, Bubbles, and the End of Fake Money? 🚨

- 20 Films Where the Opening Credits Play Over a Single Continuous Shot

- ‘The Substance’ Is HBO Max’s Most-Watched Movie of the Week: Here Are the Remaining Top 10 Movies

- First Details of the ‘Avengers: Doomsday’ Teaser Leak Online

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- The 11 Elden Ring: Nightreign DLC features that would surprise and delight the biggest FromSoftware fans

2026-02-13 20:13