Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research demonstrates that reinforcement learning algorithms can develop surprisingly rich and robust communication strategies, even in complex strategic environments.

This review analyzes how reward-driven adaptation in reinforcement learning shapes information transmission and impacts welfare outcomes in settings involving algorithmic communication and Bayesian persuasion.

Traditional models of strategic communication often assume fully rational agents, yet real-world advice is frequently generated by adaptive algorithms. This paper, ‘The Algorithmic Advantage: How Reinforcement Learning Generates Rich Communication’, analyzes communication dynamics when advice stems from a reinforcement learning algorithm, revealing that reward-driven adaptation can robustly lead to informative communication, even from initially uninformative policies. Notably, with misaligned preferences, learning generates cyclical patterns that sustain higher payoffs than any static equilibrium. Does this suggest that algorithmic communication can overcome limitations inherent in rational-based models and unlock new possibilities for information transmission?

The Illusion of Transparency: Why Complete Information Is a Myth

Conventional models of communication frequently operate under the assumption that all parties possess complete and equal access to information, a scenario rarely mirrored in practice. Human interaction is, instead, often characterized by information asymmetry – where individuals hold private knowledge or incentives to present information strategically. This divergence from idealized transparency impacts everything from negotiations and political discourse to everyday social exchanges. Individuals rarely reveal their true preferences or intentions fully, instead crafting messages designed to achieve specific outcomes. Consequently, interpreting communicated information requires accounting not only for its literal content but also for the sender’s potential motivations and the information they choose not to share, creating a complex dynamic where meaning is often inferred rather than directly conveyed.

The ‘Cheap Talk Framework’ elegantly models communication where one party possesses private information and signals it to another, yet predicting the resulting outcome proves remarkably difficult. While game theory suggests optimal signaling strategies for both parties, simulations consistently demonstrate that complete and honest revelation of information is frequently not the most effective approach. Instead, strategic ambiguity and partial disclosure often yield better results, highlighting that fully transparent communication isn’t always rational or beneficial. This arises because the informed party can manipulate signals to influence the receiver’s beliefs and actions, and the receiver must account for this potential deception. Consequently, even with perfectly rational actors employing optimal strategies, communication often falls short of complete information transfer, revealing the inherent limits of transparency in real-world interactions.

Adaptive Signaling: Learning to Communicate Effectively

Q-Learning is employed as the reinforcement learning algorithm to enable dynamic refinement of the sender’s messaging policy within the Cheap Talk Framework. This involves the sender iteratively learning an optimal signaling strategy by interacting with the receiver in a simulated environment. The algorithm maintains a Q-table, which estimates the expected cumulative reward for taking a specific messaging action in a given state. Through repeated interactions, the sender updates these Q-values based on the received feedback, progressively improving its ability to convey information effectively and influencing the receiver’s actions. The state space is defined by the sender’s private information, and the action space consists of the available messages. The reward function is designed to incentivize truthful signaling and maximize overall welfare, guiding the learning process towards a superior equilibrium compared to static messaging strategies.

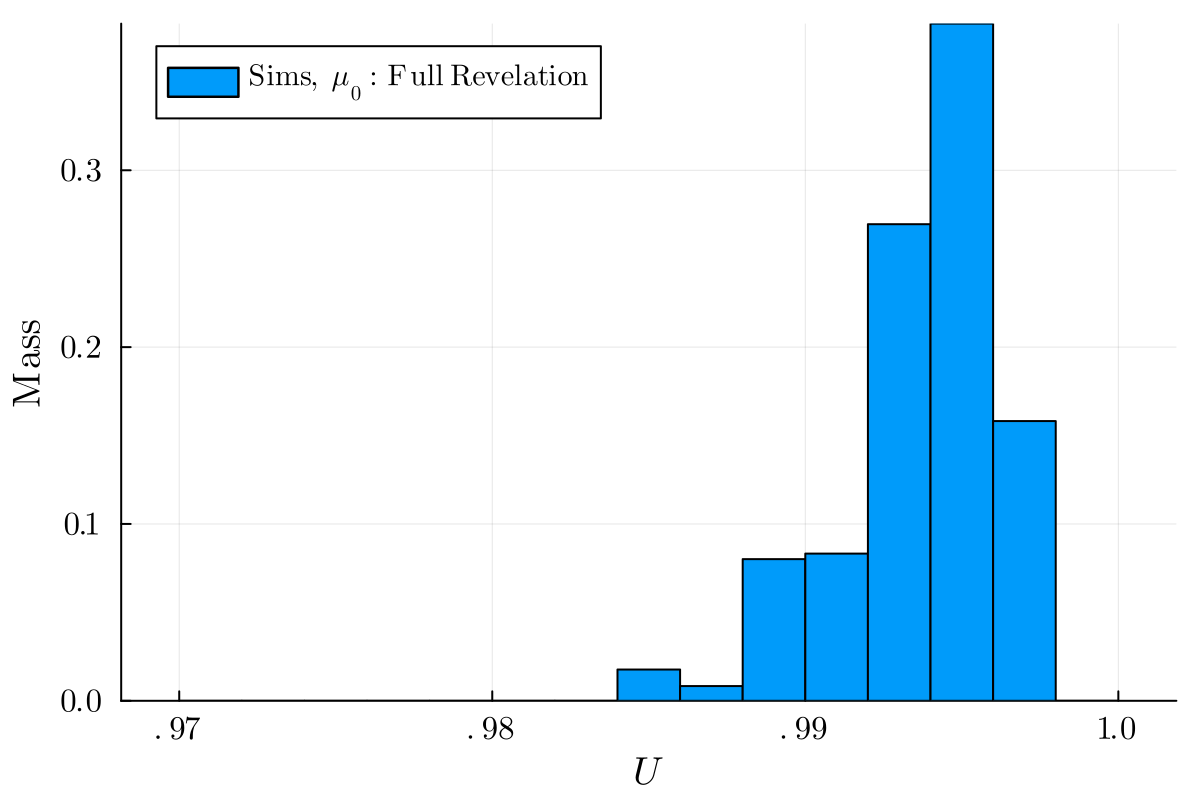

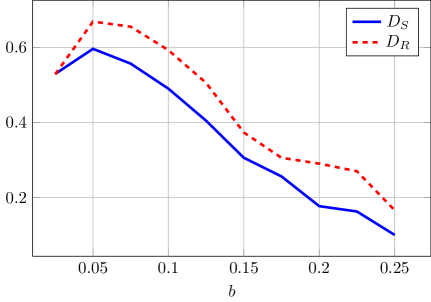

Reward-driven adaptation within the Q-learning algorithm operates by modulating the probability of message transmission based on observed outcomes. Successful messages – those resulting in the receiver taking the desired action – are positively reinforced, increasing their future likelihood. Conversely, messages that fail to elicit the desired response are attenuated, decreasing their probability of future use. This iterative process allows the sender to dynamically refine its signaling strategy, moving towards an optimal policy that maximizes expected welfare. The algorithm’s objective is to achieve a welfare ratio exceeding 1, demonstrating performance superior to that of static, pre-defined signaling equilibria; this ratio is calculated as the achieved welfare divided by the welfare of the highest static equilibrium.

From Stability to Cycles: The Dynamics of Policy Outcomes

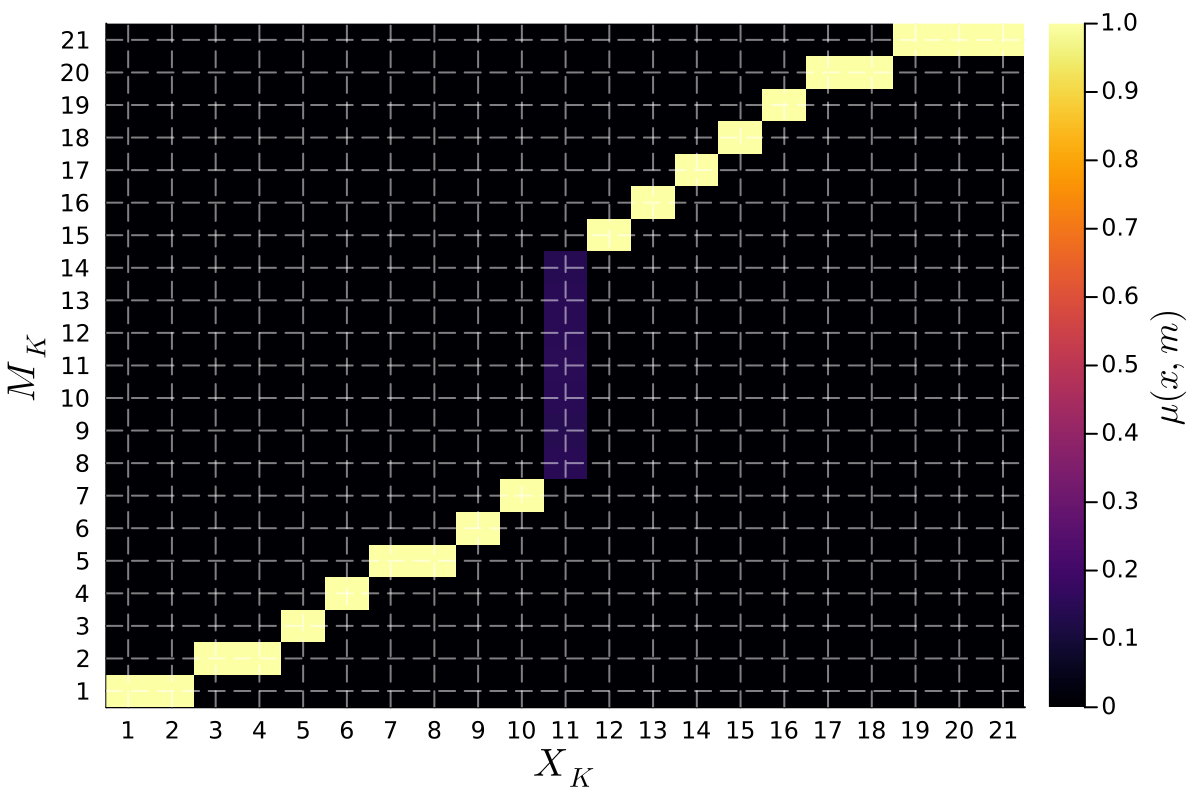

The Crawford-Sobel Equilibrium represents a stable outcome in signaling games where the sender and receiver establish a mutual understanding despite incomplete information. This equilibrium is characterized by a static messaging policy; the sender adopts a single, consistent signal, and the receiver infers a specific type or state based on that signal. Crucially, this outcome requires conditions where the cost of misrepresentation for the sender, and the cost of incorrect inference for the receiver, are balanced. When these costs align, a clear and predictable communication pattern emerges, preventing indefinite oscillation between signaling strategies and allowing for efficient information transfer. The resulting policy is a Nash equilibrium, meaning neither party has an incentive to deviate from their established strategy, given the other party’s behavior.

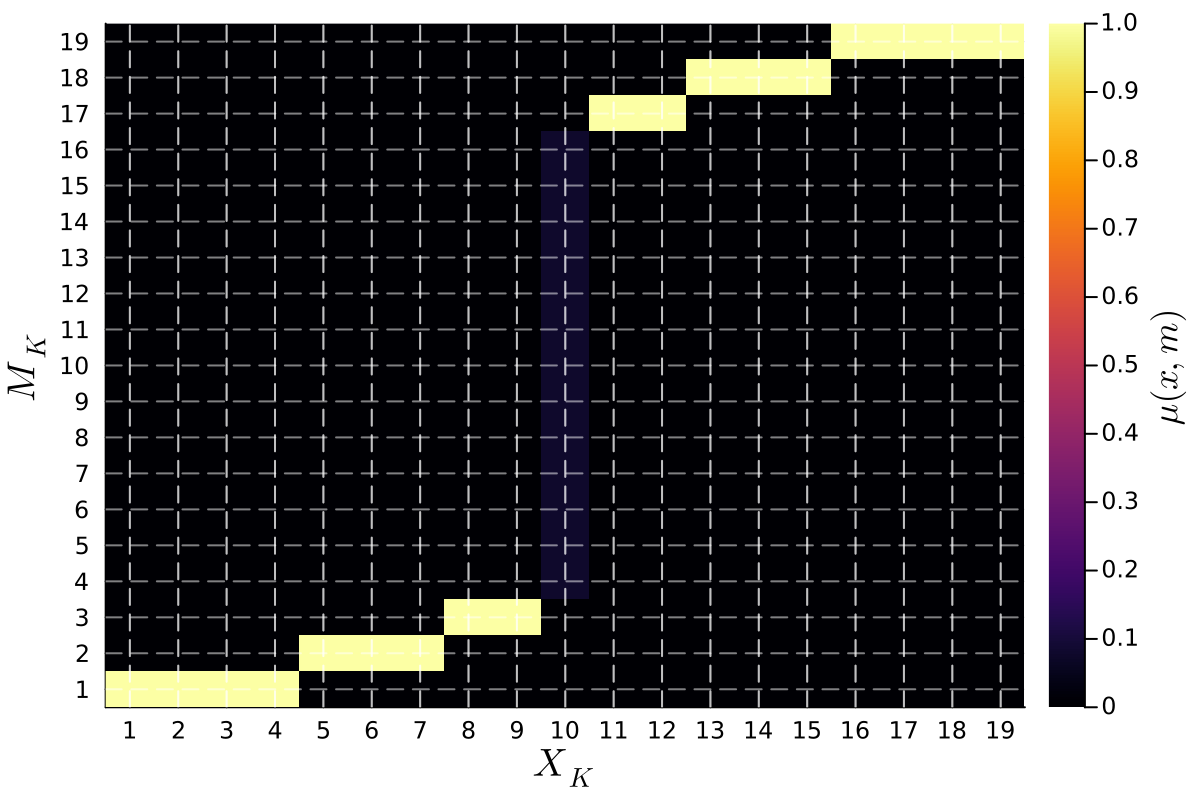

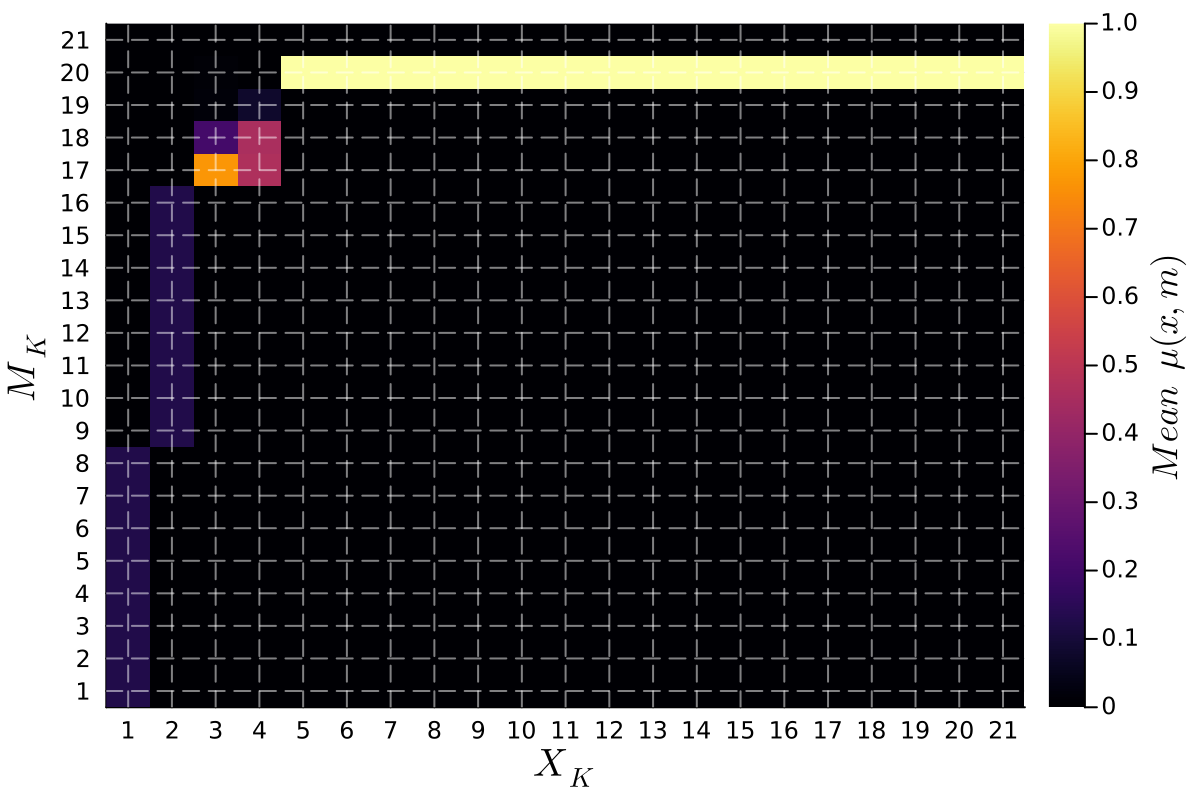

Preference bias, representing a divergence of interests between the sender and receiver, introduces instability into the learned policy and results in cyclical messaging patterns. When the sender’s optimal message differs from the receiver’s preferred information, the Q-learning algorithm fails to converge on a stable equilibrium. Instead, the sender and receiver engage in repeated, non-convergent messaging cycles as each attempts to adapt to the other’s biased preferences. This dynamic prevents the attainment of a clear understanding and leads to sustained oscillation in the messaging strategy, as neither party can reliably predict the other’s response or achieve a mutually beneficial outcome.

An increased exploration rate within the Q-learning algorithm allows the sender to identify and capitalize on nuanced advantages in signaling, potentially improving performance. However, this heightened exploration introduces instability into the learning process; while a sender can approach optimal signaling, the algorithm may not converge to a static solution. Specifically, in scenarios without preference bias, the algorithm achieves at least 98% of the maximum surplus attainable through full revelation – representing a near-optimal outcome despite the inherent instability associated with high exploration rates.

Measuring Success Beyond Information: The Importance of Welfare

Evaluating the effectiveness of communication necessitates a metric beyond simple information transfer; the concept of ‘Welfare’ provides this crucial assessment. Welfare, in this context, isn’t merely about accurate signaling, but rather the combined benefit realized by both the sender and the receiver of a message. A communication strategy isn’t successful if it conveys information perfectly but leaves one party worse off. Instead, a truly effective system maximizes the sum of payoffs – ensuring both the sender and receiver achieve a mutually advantageous outcome. This holistic approach acknowledges that communication serves a purpose – to improve collective well-being – and therefore, its success should be measured by the extent to which it achieves that improvement, quantified as a ratio where values exceeding one indicate a net positive gain for all involved.

Research indicates that maximizing communicative welfare – the combined benefit to both the sender and receiver of information – isn’t necessarily achieved through static, unchanging communication strategies. Simulations reveal that both established equilibrium points, such as the Crawford-Sobel Equilibrium, and dynamically adjusted, even cyclical, communication policies can, under certain conditions, yield superior outcomes. Critically, these simulations demonstrate a welfare ratio exceeding 1, indicating a measurable improvement in overall payoff compared to traditional static benchmarks. This suggests that flexible communication approaches, capable of adapting to evolving circumstances, hold significant potential for enhancing the efficiency and benefits derived from information exchange, challenging the assumption that a stable equilibrium always represents the optimal solution.

A consistently applied communication strategy, termed a ‘Connected Policy’, demonstrably enhances the effectiveness of information transfer and ultimately boosts collective well-being. This approach centers on utilizing the same messages across states that share inherent relationships, thereby fostering greater predictability for the receiver. When messages maintain consistent meaning across related scenarios, ambiguity is reduced and the receiver can more accurately infer the sender’s intent. Simulations reveal that such interconnectedness isn’t merely about clarity; it actively improves overall welfare – the combined benefit to both communicating parties – by streamlining interactions and minimizing the potential for misinterpretation. The result is a more efficient and mutually beneficial exchange of information, solidifying the value of a coherent messaging framework.

The pursuit of algorithmic communication, as detailed in the analysis of reinforcement learning strategies, reveals a fascinating dynamic. It isn’t about discovering inherent truths, but rather about iteratively refining strategies against the backdrop of inherent variance. As Richard Feynman observed, “The first principle is that you must not fool yourself – and you are the easiest person to fool.” This echoes the paper’s core insight: even ‘cheap talk’ algorithms, driven by reward-driven adaptation, can generate robustly informative communication not through perfect information transfer, but through repeated interaction and the constant disproving of initial hypotheses. The system doesn’t know the optimal communication; it learns it by failing repeatedly, ultimately rationalizing variance into a functional signal.

What’s Next?

The observation that reward-driven adaptation can yield surprisingly rich communication, even in the absence of explicitly optimized information transfer, feels less like a revelation and more like a restatement of an old principle: incentives matter. Yet, the specific mechanisms by which these algorithms achieve robustness against noise and imperfect observability remain stubbornly opaque. One suspects the ‘insight’ isn’t so much about discovering a new form of communication, but rather about the limitations of current analytical tools for characterizing complex adaptive systems. A model isn’t a mirror of reality-it’s a mirror of its maker, and current models struggle to capture the subtle interplay between learning, strategy, and environment.

Future work should resist the temptation to treat these algorithms as ‘black boxes’ delivering optimal solutions. The focus must shift toward understanding why certain communication patterns emerge, and, crucially, what conditions invalidate them. What’s the significance level of these improvements over static equilibria? Are these algorithms merely exploiting statistical regularities, or are they genuinely capable of nuanced persuasion? The question isn’t whether reinforcement learning can communicate, but whether it communicates in ways that are qualitatively different from, and potentially more fragile than, the communication predicted by established game-theoretic frameworks.

Finally, the welfare implications deserve further scrutiny. Robust communication is not necessarily beneficial communication. The paper hints at potential divergence between informational efficiency and social welfare-a point that should be explored with considerably more rigor. After all, an algorithm capable of persuasive communication is, by definition, capable of manipulative communication. The challenge, then, isn’t just to build algorithms that talk, but to understand the ethics of what they say.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.12035.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Monster Hunter Stories 3: Twisted Reflection launches on March 13, 2026 for PS5, Xbox Series, Switch 2, and PC

- Here Are the Best TV Shows to Stream this Weekend on Paramount+, Including ‘48 Hours’

- 🚨 Kiyosaki’s Doomsday Dance: Bitcoin, Bubbles, and the End of Fake Money? 🚨

- 20 Films Where the Opening Credits Play Over a Single Continuous Shot

- ‘The Substance’ Is HBO Max’s Most-Watched Movie of the Week: Here Are the Remaining Top 10 Movies

- First Details of the ‘Avengers: Doomsday’ Teaser Leak Online

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- The 11 Elden Ring: Nightreign DLC features that would surprise and delight the biggest FromSoftware fans

2026-02-13 16:35