Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that even before training, the architecture of transformer models introduces systematic biases affecting how they process information.

Randomly initialized transformers exhibit inherent biases in token preferences and internal representations, with implications for model fingerprinting and architectural design.

Despite the common assumption that transformer architectures are structurally neutral at initialization, recent work in ‘Transformers Are Born Biased: Structural Inductive Biases at Random Initialization and Their Practical Consequences’ reveals systematic biases emerge even before training begins. This paper demonstrates that randomly initialized transformers exhibit strong token preferences and a contraction of hidden representations driven by interactions between MLP activations and self-attention-biases that persist throughout pretraining and establish a stable model identity. These initialization-induced biases not only enable reliable model fingerprinting via a novel method called SeedPrint, but also provide a mechanistic explanation for the attention-sink phenomenon. Could understanding these inherent biases lead to more efficient training and fundamentally improved transformer architectures?

The Transformer’s Foundation: Parallel Processing and Emergent Abilities

The Transformer architecture has rapidly become foundational to the field of Natural Language Processing, eclipsing previous recurrent and convolutional approaches with its parallelizable design and superior performance. This breakthrough is largely attributable to the mechanism of self-attention, which allows the model to weigh the importance of different words in a sequence, capturing long-range dependencies more effectively than prior methods. Consequently, Transformers now underpin state-of-the-art results across a remarkably diverse range of tasks – from machine translation and text summarization to question answering and code generation. Their scalability, coupled with innovations like positional encoding and multi-head attention, has enabled the training of increasingly large and powerful models, continually pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in artificial intelligence and solidifying the Transformer’s position as a central component of modern NLP systems.

The efficacy of modern Transformer models is inextricably linked to the synergistic relationship between powerful optimization algorithms and massive datasets. Algorithms like AdamWOptimizer don’t simply guide the learning process; they navigate the extraordinarily complex, high-dimensional landscape of model parameters, efficiently converging on solutions that minimize prediction errors. This optimization, however, is critically dependent on the scale and quality of the training data; datasets such as OpenWebTextDataset, comprising billions of tokens, provide the necessary breadth of examples for the model to generalize effectively. Without such large-scale data, even the most sophisticated optimizer would struggle to overcome the limitations imposed by insufficient training signal, resulting in models prone to overfitting or lacking the capacity to perform complex natural language tasks. The combination allows for the creation of models capable of exhibiting emergent abilities previously unattainable.

The very genesis of a Transformer model’s performance lies within its initial random weights, established through a process called RandomInitialization. These aren’t simply neutral starting points; they exert a surprisingly strong influence on the model’s eventual capabilities and, critically, its inherent biases. Research demonstrates that distinct random initializations can lead to dramatically different outcomes, even with identical training data and hyperparameters. Fortunately, a technique called fingerprinting allows for the reliable detection of these initial weight configurations, enabling researchers to analyze how these early conditions shape the model’s behavior and potentially mitigate unwanted biases before extensive training occurs. This ability to ‘read’ the model’s origins is becoming increasingly vital as these powerful systems are deployed in sensitive applications, demanding accountability and fairness.

The Erosion of Meaning: Intra- and Inter-Sequence Contraction

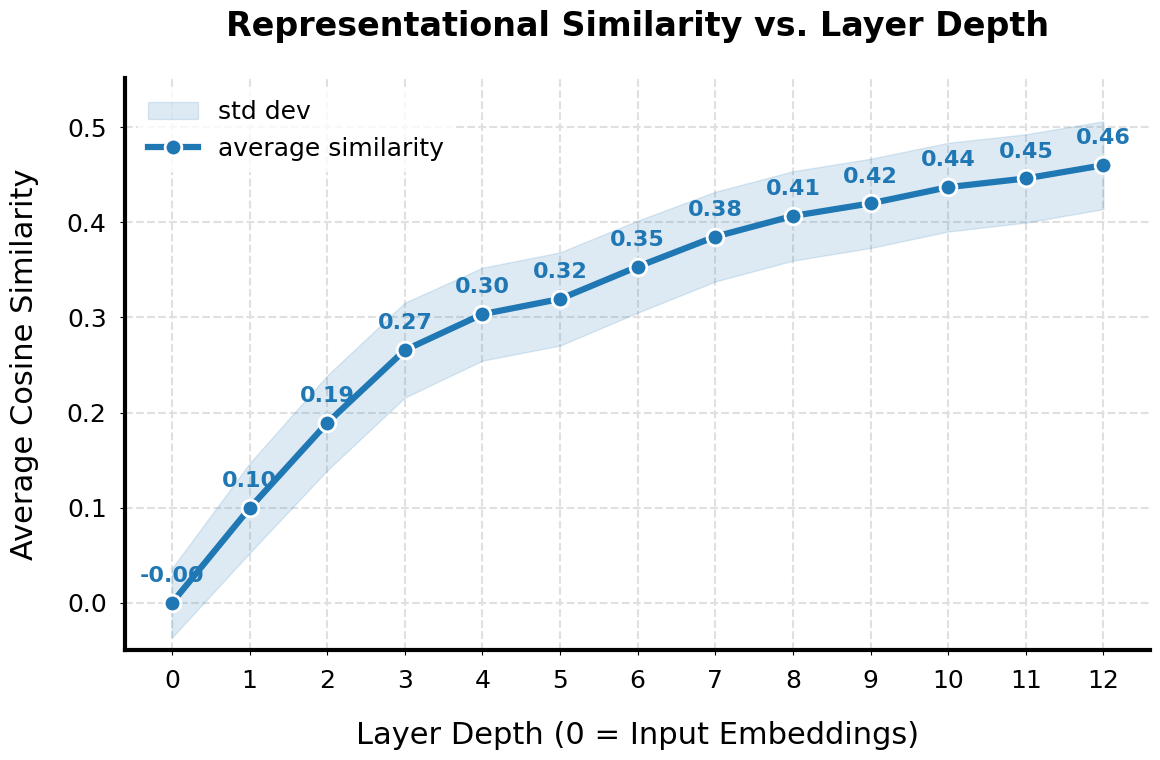

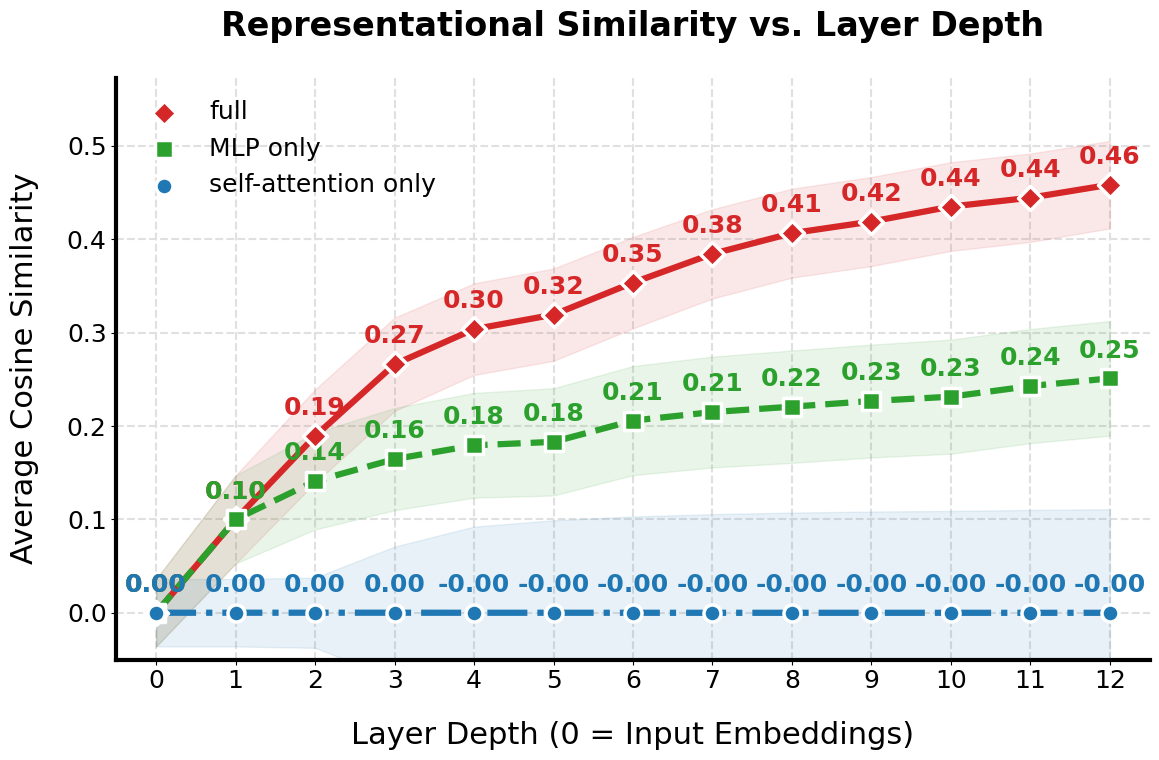

IntraSequenceContraction refers to the observed phenomenon within transformer models where the vector representations of tokens processed within a single input sequence become increasingly similar as the sequence length increases. This means that, during forward propagation, the model’s internal representations lose distinctiveness between individual tokens. Consequently, the model’s ability to differentiate the specific contribution of each token to the overall sequence meaning is diminished, leading to performance degradation on tasks requiring precise token-level understanding or long-range dependency modeling. This effect isn’t a result of identical tokens, but rather a consequence of the model’s architecture and training process, where later tokens’ representations are unduly influenced by earlier, already-processed tokens.

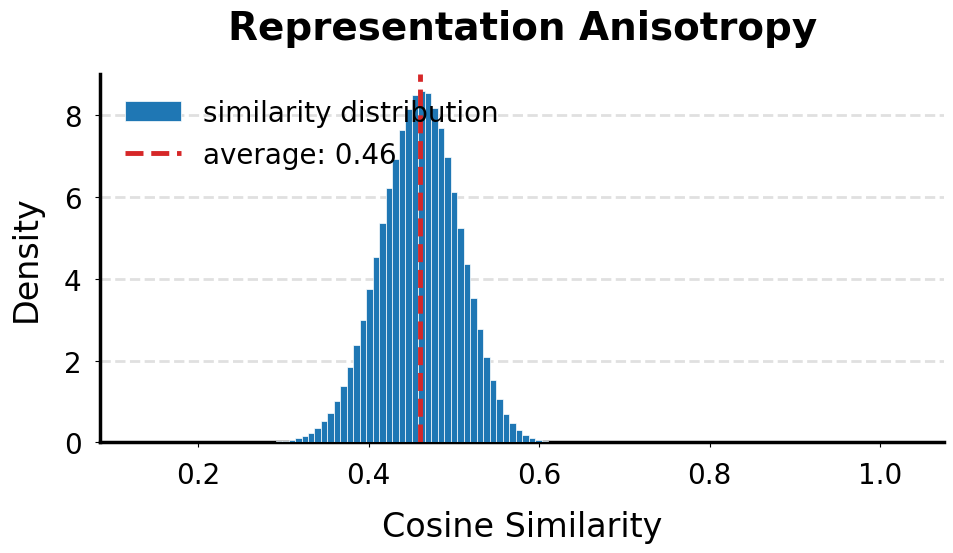

InterSequenceContraction refers to the observed convergence of representational vectors generated for different input sequences. This phenomenon indicates a reduction in the model’s ability to differentiate between distinct inputs, as the internal representations become increasingly similar regardless of the original input’s content. The effect is not simply an averaging of representations, but a genuine contraction of the representational space, leading to a loss of information that distinguishes one sequence from another. This convergence exacerbates the issues caused by IntraSequenceContraction, as both effects contribute to a diminished capacity for nuanced understanding and accurate processing of diverse inputs.

Representational contraction, specifically IntraSequenceContraction and InterSequenceContraction, results in a quantifiable loss of information within the model’s internal representations. This loss directly degrades performance on tasks demanding detailed comprehension, such as question answering, reading comprehension, and tasks involving subtle distinctions between inputs. The degree of information loss is measurable through metrics that quantify representational similarity; higher similarity scores between token or sequence representations indicate greater contraction and a corresponding reduction in the model’s ability to differentiate between distinct elements of the input data. These metrics provide a concrete method for identifying and assessing the impact of representational collapse on model behavior.

Positional Encoding and the Emergence of Attentional Bias

Representational collapse, where distinct tokens are mapped to similar vector representations, is directly affected by the method of positional encoding. Distortions introduced during positional encoding – inaccuracies in representing token order – lead to what is defined as PositionalVarianceDiscrepancy. This discrepancy quantifies the degree to which the variance of positional embeddings deviates from an ideal, uniform distribution. A higher PositionalVarianceDiscrepancy indicates a greater loss of positional information, increasing the likelihood of the model incorrectly interpreting or ignoring token order, and ultimately contributing to issues within the attention mechanism.

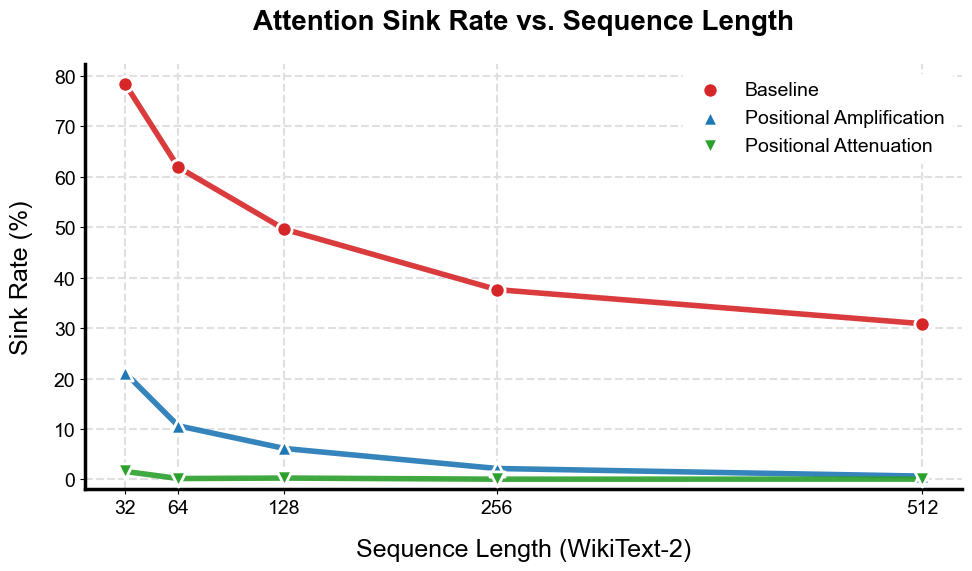

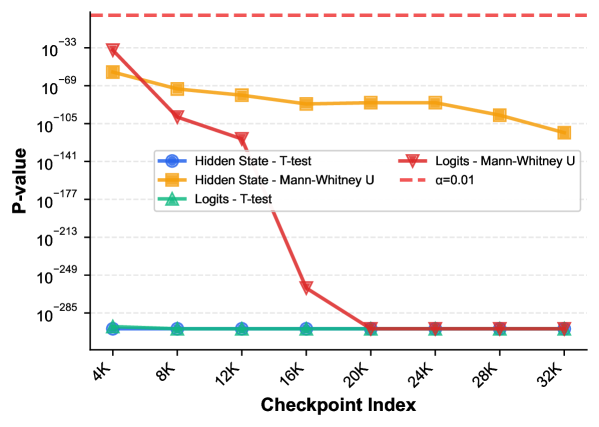

The PositionalVarianceDiscrepancy, arising from distortions in positional encoding, directly impacts the attention mechanism within the Transformer architecture, leading to a phenomenon termed AttentionSink. This effect is characterized by a disproportionate allocation of attention weights to the initial token of an input sequence. Consequently, subsequent tokens receive comparatively less attention, hindering the model’s ability to effectively process and integrate information across the entire sequence length. Statistical analysis demonstrates the significance of this effect, consistently yielding p-values below 0.01, indicating that the observed attention bias is not attributable to random chance.

Within the Transformer architecture, several techniques – RoPE (Rotary Positional Embeddings), SwiGLU (Swish-Gated Linear Unit), and RMSNorm (Root Mean Square Layer Normalization) – are implemented to address issues stemming from positional encoding, specifically the AttentionSink phenomenon. Our analysis, utilizing Cosine Similarity as a key metric, demonstrates that these interventions yield a statistically significant reduction in attention disproportionately focused on the initial tokens of a sequence. However, it is important to note that while these methods demonstrably alleviate the AttentionSink effect, they do not fully eliminate it; residual attention bias remains even with their application.

Statistical analysis confirms the presence of the AttentionSink effect, indicating that the observed disproportionate focus on the initial token in a sequence is not attributable to random chance. Testing consistently yields p-values below 0.01, establishing statistical significance across multiple experimental runs. This low p-value threshold demonstrates a high level of confidence that the observed AttentionSink phenomenon is a genuine characteristic of the model’s behavior under the tested conditions, rather than a result of statistical noise. The consistent statistical significance supports the need for interventions designed to address this bias in attention distribution.

Tracing the Lineage of Large Models: The Power of Fingerprinting

The process of RandomInitialization in large language models relies on a pseudo-random number generator, requiring a starting value known as the initial random seed. This seed dictates the initial weights assigned to the model’s parameters; even minor variations in the seed result in substantially different weight configurations. Consequently, the initial random seed functions as a unique identifier, or ‘fingerprint’, for each specific model instance created. Because the seed determines the initial state, it enables the precise replication of a model’s configuration, facilitating controlled experimentation and comparative analysis across different model instances. Without tracking this seed, reproducing specific model behaviors becomes significantly more difficult due to the inherent stochasticity of the training process.

SeedPrint is a methodology for tracking and uniquely identifying individual instances of large models generated through random initialization. This is achieved by recording the initial random seed used during model creation, effectively creating a traceable ‘fingerprint’ for each instance. The ability to precisely identify models based on their seed enables controlled experimentation and reliable replication of results; researchers can consistently reproduce specific model behaviors by reinstantiating the model with the same seed. This level of control is critical for debugging, comparative analysis, and ensuring the validity of research findings in the rapidly evolving field of large language models.

Establishing a clear relationship between the initial random seed, the resulting representational dynamics within a large language model, and observable model behavior is crucial for mitigating existing limitations. This connection allows for targeted analysis of model responses and facilitates reproducibility of experimental results. Verification of this approach has been conducted using Kendall’s Tau correlation, demonstrating a statistically significant association between the seed and subsequent model characteristics. This method enables researchers to not only track individual model instances but also to systematically investigate how variations in the initial seed impact model performance and generalization capabilities.

Experimental results indicate a statistically significant differentiation between large language models initialized with distinct random seeds. Comparison of model fingerprints – representations of internal states – consistently yields a p-value greater than 0.01. This finding demonstrates the reliability of using initial seed as a unique identifier for model instances and confirms that variations in initialization lead to demonstrably different model behaviors, detectable through fingerprint analysis. The observed statistical significance supports the use of this method for tracking and reproducing experimental results.

The study illuminates how even at their genesis, transformer models aren’t blank slates, but rather inherit structural preferences – a finding resonant with Thoreau’s observation that “we are all sculptors and painters, and our palette and chisels are the things we think.” These initial biases, manifesting as token preferences and representation contraction, demonstrate that algorithms encode worldviews from the outset. The persistence of these biases post-training underscores the importance of critically examining the values embedded within automated systems, especially as these models increasingly mediate information and shape perceptions. Efficiency gains are illusory if built upon a foundation of unexamined assumptions.

Beyond Randomness: Charting a Course for Equitable Transformers

The observation that even randomly initialized transformers harbor systematic biases presents a challenge that transcends mere architectural tweaks. It suggests that the pursuit of scale, without parallel attention to the values embedded within these foundational layers, is a form of techno-centrism. Addressing these initial conditions is not simply a matter of improving performance metrics; it requires a fundamental shift toward recognizing that algorithms are not neutral, and their biases are not simply ‘washed away’ by training data.

Future work must move beyond identifying that biases exist, and focus on developing methodologies for characterizing what those biases are, and more importantly, how they propagate through the entire model lifecycle. The potential for model fingerprinting, while intriguing, raises ethical concerns regarding privacy and accountability. Ensuring fairness is part of the engineering discipline, and requires a proactive approach to bias mitigation, rather than reactive analysis of deployed systems.

Ultimately, the field must confront the unsettling possibility that certain architectural choices inherently favor specific representations, potentially marginalizing others. The goal should not be to eliminate all bias – an impossible and perhaps undesirable task – but to achieve a greater degree of transparency and control over the values encoded within these increasingly powerful systems. The question is not simply “can it learn?” but “what does it learn, and at what cost?”

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05927.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 21 Movies Filmed in Real Abandoned Locations

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- The 11 Elden Ring: Nightreign DLC features that would surprise and delight the biggest FromSoftware fans

- 10 Hulu Originals You’re Missing Out On

- 39th Developer Notes: 2.5th Anniversary Update

- Gold Rate Forecast

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- PLURIBUS’ Best Moments Are Also Its Smallest

- 15 Western TV Series That Flip the Genre on Its Head

- Rewriting the Future: Removing Unwanted Knowledge from AI Models

2026-02-09 01:25