Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research demonstrates that a distribution-based approach can match or exceed the performance of deep learning methods in complex clustering tasks.

This paper introduces a Cluster-as-Distribution framework that leverages kernel methods and dimensionality reduction to achieve state-of-the-art results without complex representation learning.

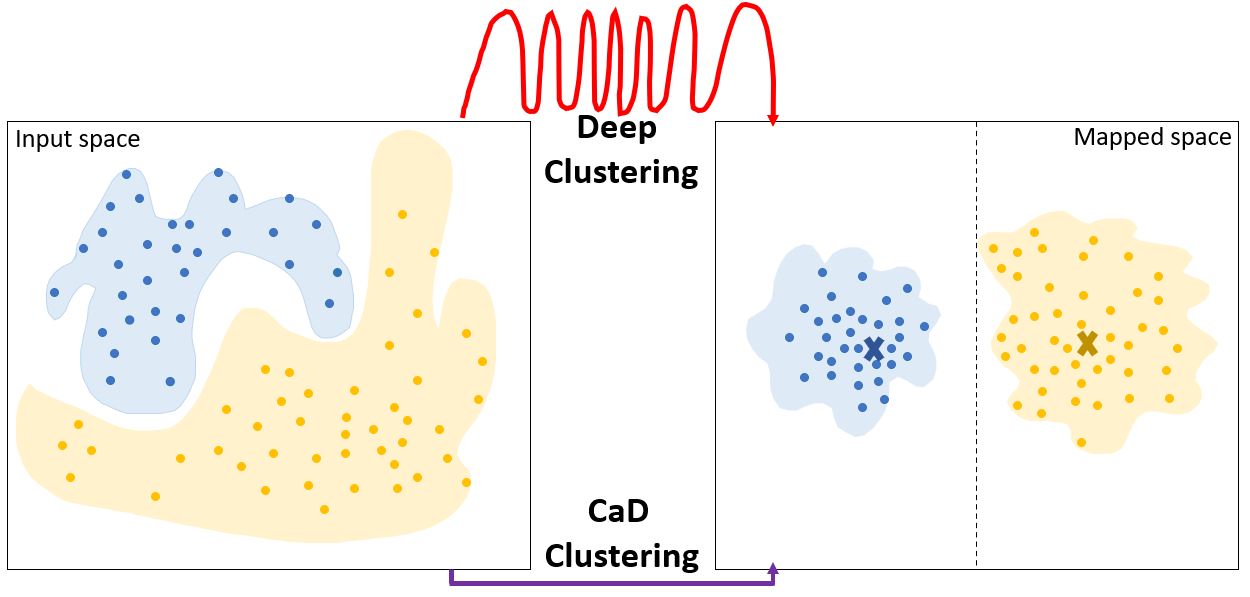

Despite claims of superior performance, deep clustering methods often fail to demonstrably overcome the fundamental limitations of traditional approaches like k-means, particularly regarding the discovery of clusters with complex geometries. This paper, ‘How to Achieve the Intended Aim of Deep Clustering Now, without Deep Learning’, investigates this paradox by challenging the necessity of deep learning for achieving the stated goals of deep clustering. We demonstrate that a non-deep learning approach-leveraging distributional information via a ‘Cluster-as-Distribution’ framework-can effectively address limitations in discerning clusters of arbitrary shapes, sizes, and densities, often outperforming deep learning methods. Does this suggest that the true power of deep clustering lies not in complex representation learning, but in effectively capturing and utilizing underlying data distributions?

The Limits of Point-to-Point Thinking

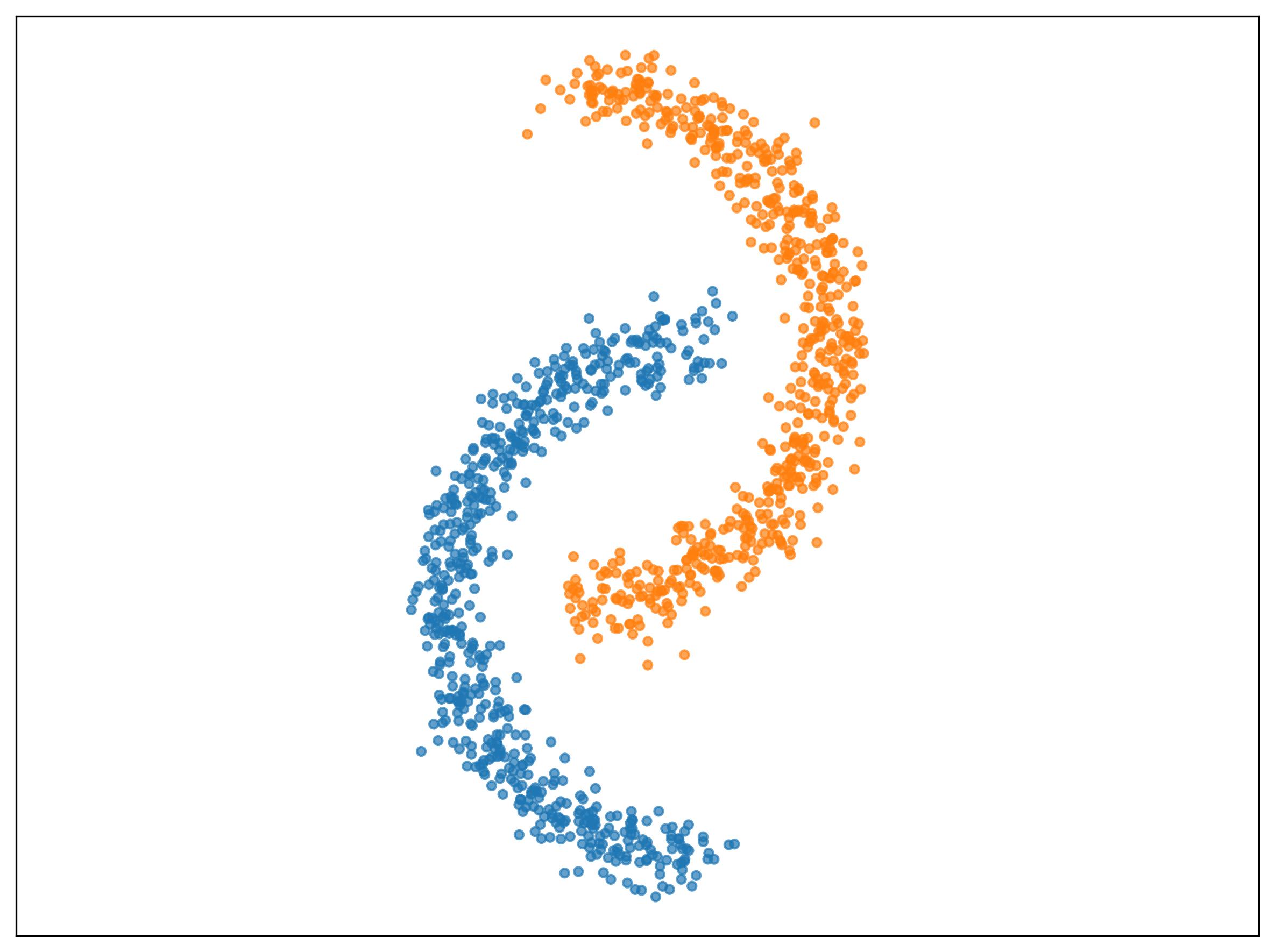

Many conventional clustering algorithms, such as k-means, operate on the principle of point-to-point similarity, evaluating the proximity of individual data points to define group membership. This methodology fundamentally assumes that each data point represents a discrete, independent entity – a clear separation between observations is implied. Consequently, these algorithms excel when clusters are well-defined and characterized by strong internal cohesion and clear boundaries. However, this reliance on direct point comparisons limits their capacity to identify more nuanced relationships, such as hierarchical structures or overlapping communities, where the essence of a cluster isn’t simply a collection of nearby points, but a complex interplay of shared attributes or contextual relationships. The inherent assumption of distinct entities therefore restricts the ability of these techniques to uncover all potential underlying data structures.

Traditional clustering algorithms often falter when confronted with datasets lacking clear boundaries between groups. These methods, frequently reliant on calculating distances between data points, presume that clusters are compact and well-separated, a condition rarely met in real-world scenarios. Complex datasets may exhibit overlapping memberships, irregular shapes, or varying densities, rendering simple distance metrics ineffective at discerning meaningful structure. For instance, data exhibiting hierarchical relationships, or those influenced by non-Euclidean spaces, will likely produce suboptimal or misleading results. Consequently, the inherent limitations of point-to-point similarity hinder the accurate identification of clusters in data where relationships are nuanced and not easily captured by straightforward distance calculations.

Many conventional clustering algorithms operate under assumptions that restrict their ability to fully reveal the organization within complex datasets. These methods often excel when identifying tightly-knit, spherical clusters based on direct similarity between data points, but falter when faced with non-convex shapes, varying densities, or hierarchical relationships. The inherent limitation stems from a reliance on predefined distance metrics and the presumption that meaningful groupings are always readily apparent through simple proximity; consequently, intricate structures such as manifolds, nested clusters, or data exhibiting strong correlations along multiple, non-Euclidean dimensions can remain hidden. This means that even with substantial computational power, certain underlying patterns within the data may be fundamentally undetectable using these established techniques, necessitating exploration of alternative approaches capable of discerning more nuanced data topologies.

From Points to Distributions: A More Holistic View

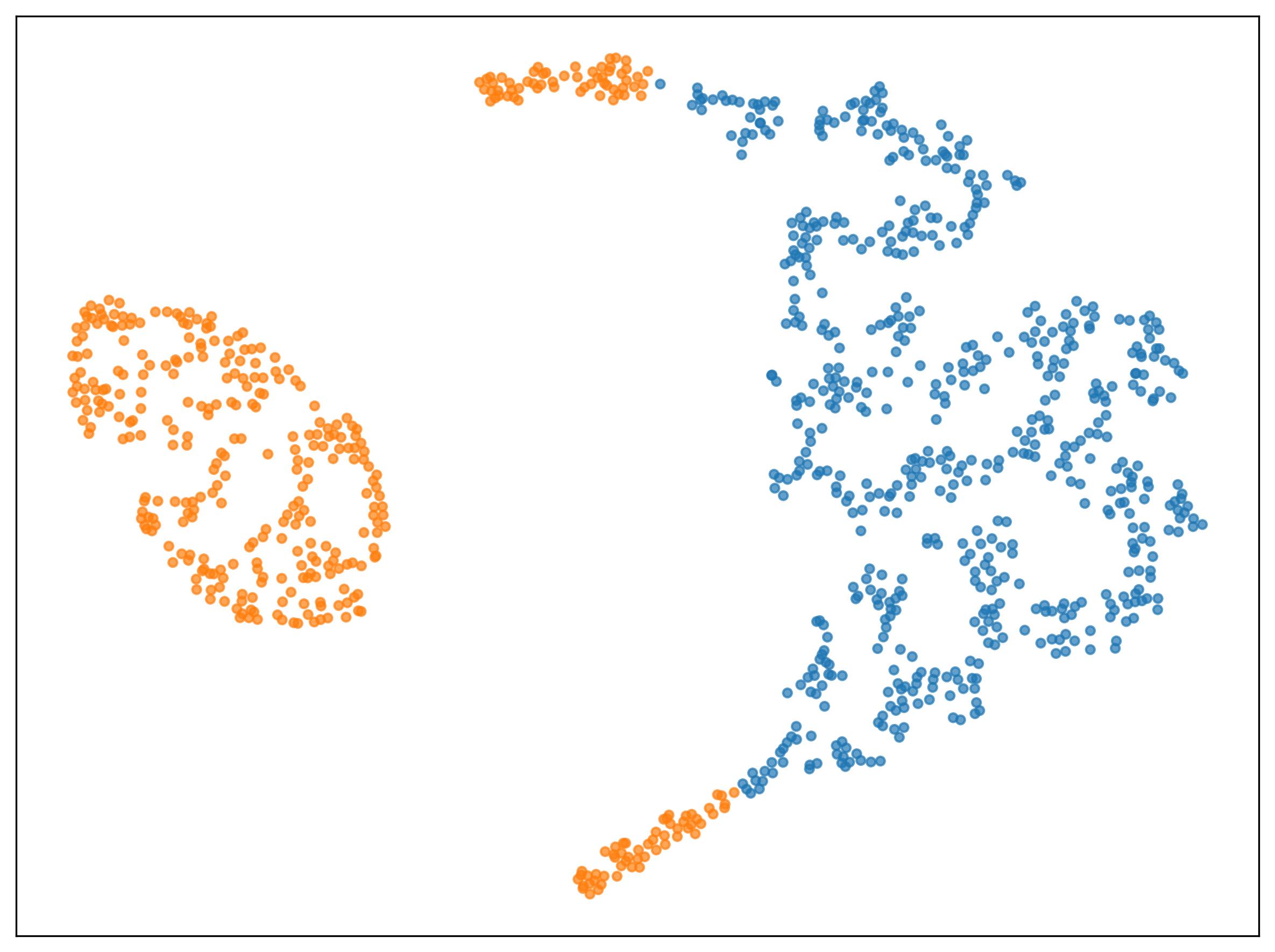

Traditional clustering algorithms typically define clusters based on the proximity of discrete data points, often using metrics like Euclidean distance. Cluster-as-Distribution Clustering departs from this approach by characterizing each cluster not as a collection of points, but as a probability distribution. This means a cluster is defined by the likelihood of observing particular data values within its boundaries, effectively representing the cluster’s overall shape and spread. Instead of assigning a data point to the nearest centroid, this method assesses the similarity between the data point’s distribution and the distribution representing each cluster. This allows for the identification of clusters with complex geometries and handles overlapping data more effectively than point-based methods, as the similarity is determined by distributional characteristics rather than simple spatial proximity.

Distributional Kernels offer a method for quantifying the similarity between probability distributions by mapping them into a potentially infinite-dimensional feature space. Unlike point-wise comparisons which assess proximity based on individual data points, these kernels consider the entire distributional shape, capturing more complex relationships such as varying degrees of overlap or divergence. This is achieved by defining a kernel function k(P, Q) that returns a scalar value representing the similarity between distributions P and Q, without explicitly computing the distance in the feature space. Common examples include kernels based on characteristic functions or optimal transport, allowing for the detection of similarity even when distributions do not have identical means or variances.

Kernel-Based Clustering (KBC) builds upon the cluster-as-distribution approach by utilizing Kernel Mean Embedding (KME) to map probability distributions into a reproducing kernel Hilbert space (RKHS). This transformation allows for the application of standard kernel-based clustering algorithms, such as those based on Gaussian kernels, to distributions directly. The KME effectively represents each distribution as a single point in the feature space, enabling efficient computation of distances and cluster assignments. Performance evaluations on the 1024-dimensional COIL-20 dataset demonstrate the efficacy of KBC, achieving Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) scores of 0.98, indicating a high degree of agreement between the identified clusters and the ground truth labels.

Deep Learning: Learning to See the Structure

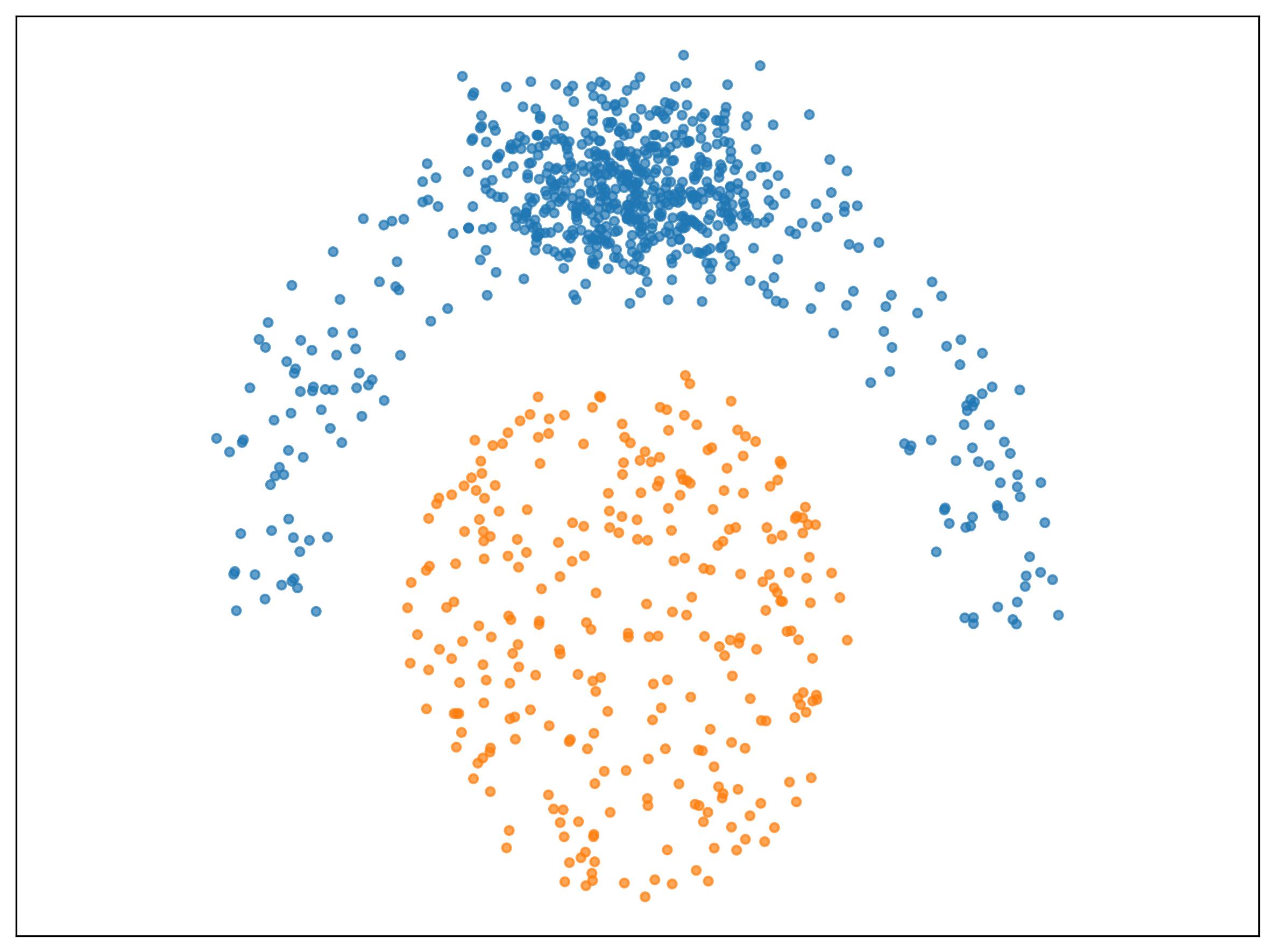

Deep clustering employs representation learning techniques – typically utilizing neural networks like autoencoders – to transform raw, high-dimensional data into lower-dimensional feature spaces where distributional clustering algorithms can be effectively applied. This process aims to learn data representations that capture the underlying structure and relationships within the dataset, enabling more accurate and robust cluster assignments. By learning these meaningful features, deep clustering overcomes limitations of traditional methods that rely on hand-engineered features or direct application of clustering algorithms to the original data space. The learned representations facilitate the identification of complex, non-linear patterns, improving the performance of subsequent clustering steps based on distributional similarity.

Deep Embedded Clustering (DEC) and Improved Deep Embedded Clustering (IDEC) employ autoencoders to reduce the dimensionality of input data into a lower-dimensional embedding space. This embedding is designed to be more amenable to clustering algorithms. Crucially, these methods simultaneously optimize both the autoencoder’s reconstruction ability and the cluster assignments. This joint optimization is achieved through the incorporation of a Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence term in the loss function. The KL divergence measures the difference between the predicted cluster distribution for each data point and a target distribution, encouraging data points to form well-separated clusters in the embedding space. By minimizing this divergence, DEC and IDEC directly encourage the formation of cohesive and distinct clusters during the representation learning process.

Deep learning methods for distributional feature extraction demonstrate particular efficacy with high-dimensional data by mitigating the effects of the curse of dimensionality and enabling the identification of complex, subtle patterns. While these approaches generally improve performance over traditional clustering techniques in such datasets, the Kernel-Based Clustering (KBC) method consistently achieves superior results. Specifically, on the w100Gaussians dataset, KBC attained perfect Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) scores, a benchmark where both traditional and other deep learning-based clustering methods failed to produce accurate groupings.

Beyond the Horizon: Contrastive Learning and a New Era

Contrastive clustering represents a significant shift in how algorithms identify patterns within data, moving beyond traditional methods that often struggle with noisy or complex datasets. This approach operates on the principle of representation learning, where the algorithm actively learns to map similar data points closer together in a feature space while simultaneously pushing dissimilar points further apart. By explicitly defining relationships between data instances – emphasizing what makes them alike or different – the resulting cluster assignments become more resilient and meaningful. This ‘pull and push’ mechanism allows the algorithm to construct robust feature representations that are less sensitive to irrelevant variations, ultimately leading to improved clustering accuracy and the ability to generalize effectively to unseen data. The technique’s effectiveness stems from its capacity to distill the essential characteristics of each cluster, creating a clearer separation between groups and enhancing the overall quality of the discovered patterns.

The efficacy of modern clustering techniques increasingly hinges on their ability to discern and leverage the inherent structure within data. Rather than treating all features equally, these methods focus on learning data representations that highlight meaningful patterns and relationships. This approach enables algorithms to not only identify clusters more accurately in the given dataset, but also to generalize effectively to unseen data. By capturing the underlying geometry of the data distribution, these learned representations become more robust to noise and irrelevant variations, ultimately leading to improved performance across diverse applications – a principle demonstrated by recent advancements in contrastive clustering that significantly outperform traditional methods in complex datasets like single-cell transcriptomics.

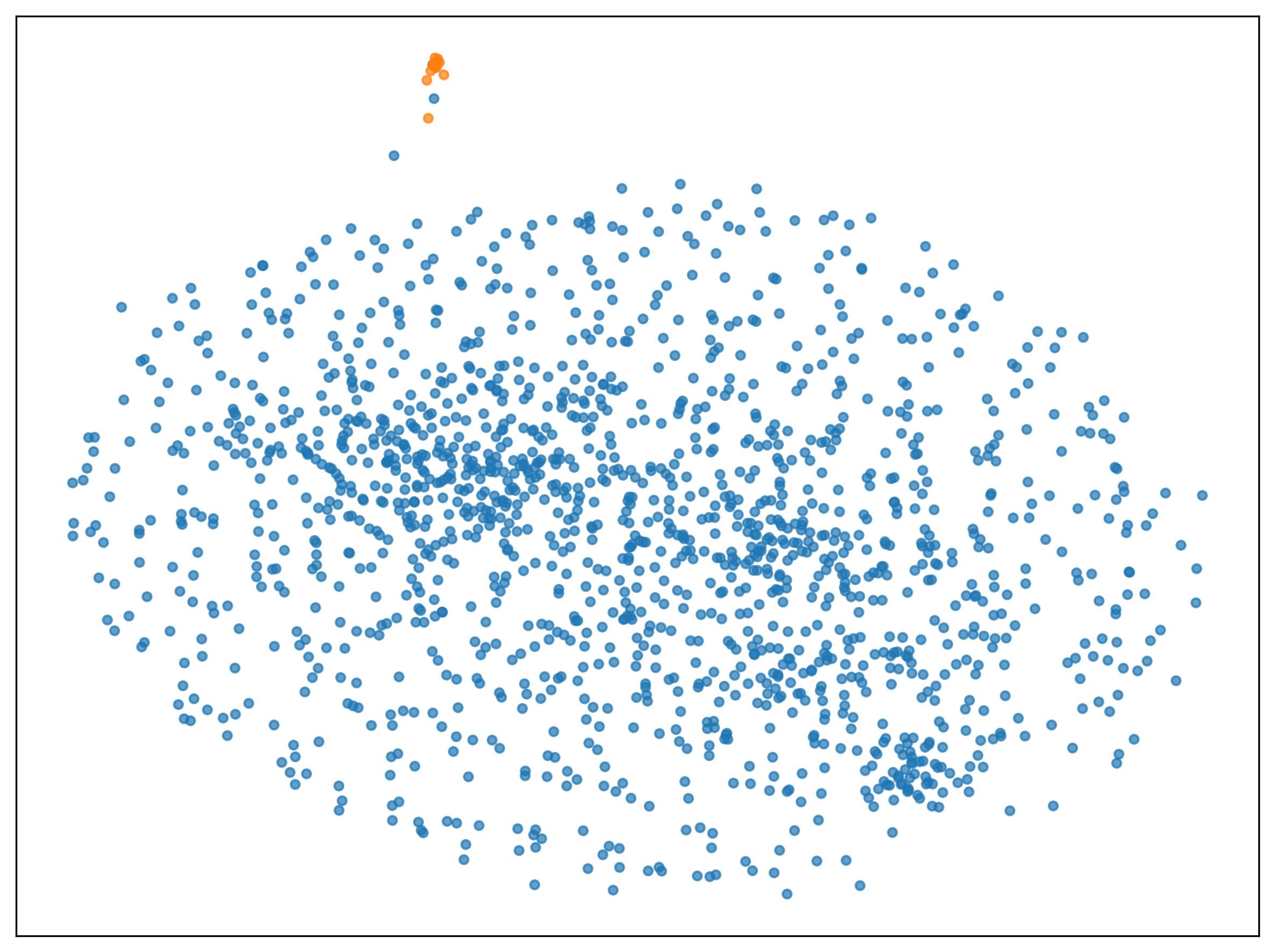

Recent progress in clustering techniques, particularly contrastive learning methods, is poised to revolutionize data analysis and informed decision-making across diverse fields. Demonstrating this potential, Kernel-Based Clustering (KBC) has achieved a Normalized Mutual Information (NMI) score of 0.87 when applied to the challenging Tutorial single-cell transcriptomics dataset. This result signifies a substantial leap forward, as competing methods, namely IDEC and CC, produced NMI scores approaching zero on the same dataset. Such improvements highlight the ability of these advanced clustering approaches to effectively discern meaningful patterns within complex biological data, and suggest broader applicability to other domains requiring sophisticated data segmentation and interpretation.

The pursuit of elegant solutions in clustering, as outlined in this paper, invariably reminds one of the cyclical nature of technology. This work proposes a return to distributional kernel methods – a seemingly less ‘revolutionary’ approach – yet achieves competitive results without the complexities of deep learning. As Bertrand Russell observed, “The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.” The authors demonstrate that the ‘old idea’ of focusing on distributional characteristics within a kernel framework is remarkably resilient, especially when confronting the inherent challenges of high-dimensional data and the limitations of representation learning. It’s a familiar pattern: a complex system is initially lauded, then slowly revealed to be unnecessarily intricate, only for a simpler, more direct approach to re-emerge.

Where Do We Go From Here?

The demonstrated efficacy of a distribution-based approach to clustering, bypassing the now-ubiquitous deep learning pipeline, invites a certain… weariness. It seems the field chases complexity for its own sake, convinced each novel architecture will fundamentally solve clustering, rather than merely re-package the same issues in shinier layers. The authors rightly point out limitations in how ‘cluster quality’ is even defined, and that remains a stubbornly persistent problem. Better metrics won’t magically create meaningful clusters, of course; they’ll just give production systems more elegant ways to fail.

Future work will undoubtedly focus on scaling these kernel methods to truly massive datasets – the usual trade-off between computational cost and statistical significance. One anticipates a flurry of papers proposing ‘efficient’ approximations, each introducing its own subtle biases and requiring increasingly elaborate hyperparameter tuning. It is likely that the core idea – treating clusters as distributions – will be absorbed into some larger, more convoluted framework, losing its simplicity in the process.

Ultimately, this work serves as a useful reminder: sometimes, the most impactful innovation isn’t a breakthrough, but a deliberate step back towards established principles. The elegance of avoiding complex representation learning is notable, though one suspects it will be remembered as a temporary reprieve before the next wave of ‘essential’ deep clustering components arrives. Everything new is just the old thing with worse docs.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05749.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 21 Movies Filmed in Real Abandoned Locations

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- The 11 Elden Ring: Nightreign DLC features that would surprise and delight the biggest FromSoftware fans

- 10 Hulu Originals You’re Missing Out On

- 39th Developer Notes: 2.5th Anniversary Update

- PLURIBUS’ Best Moments Are Also Its Smallest

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Top ETFs for Now: A Portfolio Manager’s Wry Take

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- Leaked Set Footage Offers First Look at “Legend of Zelda” Live-Action Film

2026-02-08 00:05