Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach leverages neural networks to refine false discovery rate control, leading to more reliable insights from high-dimensional datasets.

This paper introduces a model-based neural network method to improve the accuracy of the T-Rex selector for variable selection while maintaining approximate control of the false discovery rate.

Balancing statistical power and rigorous error control remains a central challenge in high-dimensional variable selection. The paper ‘Learning False Discovery Rate Control via Model-Based Neural Networks’ addresses this by introducing a learning-augmented enhancement to the T-Rex Selector, utilizing a neural network trained on synthetic data to more accurately estimate the false discovery rate. This refined approach enables operation closer to the desired FDR level, increasing detection of true variables while maintaining approximate control. Will this neural network-based calibration pave the way for more powerful and reliable high-dimensional inference across diverse scientific domains?

Decoding Complexity: The Challenge of High-Dimensional Data

Contemporary genomic research routinely produces datasets characterized by an enormous number of variables-often exceeding the number of sampled individuals. This high-dimensional landscape presents a significant challenge: discerning which genetic variants, proteins, or other biological factors truly influence a trait or disease, versus those arising from random chance or technical noise. Identifying these genuinely influential variables is not merely a statistical exercise; it’s fundamental to understanding complex biological systems and translating genomic discoveries into effective diagnostics and therapies. Consequently, researchers are actively developing and refining statistical methods specifically designed to navigate these data-rich environments, focusing on techniques that can reliably pinpoint causal relationships amidst a sea of potential associations. The ability to effectively reduce dimensionality and prioritize relevant variables is therefore paramount to progress in modern genomics.

While techniques like Lasso and Elastic Net are widely employed for variable selection, their application to high-dimensional genomic data presents a significant challenge regarding false discovery rates. These methods, designed for scenarios where the number of variables is less than the number of samples, often fail to adequately control for the increased risk of identifying spurious associations when applied to datasets where the opposite is true. The underlying statistical theory assumes a certain level of sparsity and signal strength, assumptions frequently violated in genomic studies. Consequently, the p-values generated by these methods can be unreliable, leading to an overestimation of the number of truly influential variables. Researchers are actively developing modified approaches and theoretical frameworks to address this limitation, striving for more robust and statistically sound variable selection in the era of large-scale genomic investigations.

Analyzing modern genomic data presents a significant computational hurdle due to the sheer volume of variables-often numbering in the tens or hundreds of thousands-and the need for rapid processing. Traditional statistical methods, while accurate on smaller datasets, become prohibitively slow and memory-intensive when applied to these high-dimensional spaces. Consequently, researchers are actively developing scalable algorithms and computational strategies, including parallel processing and approximation techniques, to manage the data efficiently. These advancements aren’t simply about speed; they are crucial for enabling timely discoveries and translating genomic insights into practical applications, as the time required for analysis directly impacts the pace of scientific progress and potential clinical interventions. Without computationally efficient methods, the wealth of genomic data risks remaining untapped, hindering advancements in personalized medicine and our understanding of complex diseases.

The T-Rex Selector: A Framework for Scalable Variable Selection

The T-Rex Selector utilizes sparse linear regression as its core methodology to pinpoint the most impactful variables within a dataset. This approach differs from traditional linear regression by intentionally driving the coefficients of irrelevant variables to zero, effectively removing them from the model. By focusing solely on the significant predictors, sparse regression enhances model interpretability and reduces overfitting. The technique achieves this by incorporating a regularization penalty – typically L1 regularization (Lasso) – during the coefficient estimation process. This penalty encourages sparsity by adding the sum of the absolute values of the coefficients to the error function, leading to a simpler, more focused model that highlights the key drivers of the observed phenomenon. \hat{\beta} = argmin_{\beta} ||y - X\beta||^2 + \lambda ||\beta||_1 , where λ controls the degree of sparsity.

The T-Rex Selector utilizes fast forward selection algorithms to mitigate the computational demands inherent in variable selection for large datasets. Specifically, it implements the Least Angle Regression (LARS) algorithm, which efficiently identifies predictive variables by sequentially adding those most correlated with the residuals. LARS achieves speed improvements over traditional forward selection by solving for multiple variables simultaneously along a piecewise linear path, rather than iteratively adding one variable at a time. This approach reduces the computational cost from O(p^2n) to O(pn) in many cases, where ‘p’ represents the number of potential predictors and ‘n’ the number of observations, enabling scalability for high-dimensional data analysis.

The T-Rex Selector incorporates dummy variables to address potential biases arising from categorical predictor variables. These binary (0 or 1) variables represent the presence or absence of a specific category within a qualitative feature, effectively converting non-numerical data into a numerical format suitable for regression analysis. By including dummy variables, the model avoids incorrectly interpreting ordinal relationships where none exist and accurately estimates the effect of each category relative to a defined baseline. This technique is critical for ensuring the robustness of the variable selection process and preventing spurious correlations driven by the underlying representation of categorical data.

Refining Statistical Rigor: Controlling False Discovery Rates

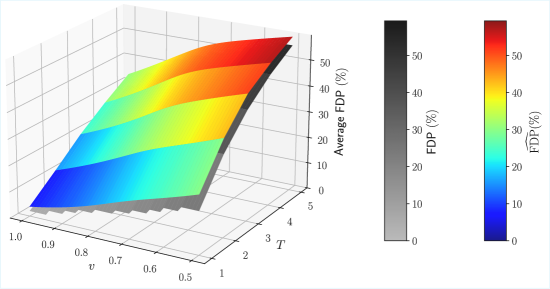

The initial implementation of the T-Rex Selector utilized an Analytical False Discovery Rate (FDP) Estimator to control for multiple hypothesis testing. This estimator, while computationally efficient, operates under simplifying assumptions regarding the distribution of p-values and effect sizes. In complex genomic datasets exhibiting characteristics such as linkage disequilibrium, population stratification, and varying effect size distributions, these assumptions are frequently violated. Consequently, the Analytical FDP Estimator can exhibit reduced accuracy in estimating the proportion of false positives, leading to suboptimal control of the FDP and potentially impacting statistical power. This limitation motivated the development of a data-driven approach, the Learned FDP Estimator, to more accurately model the complex relationships within these datasets.

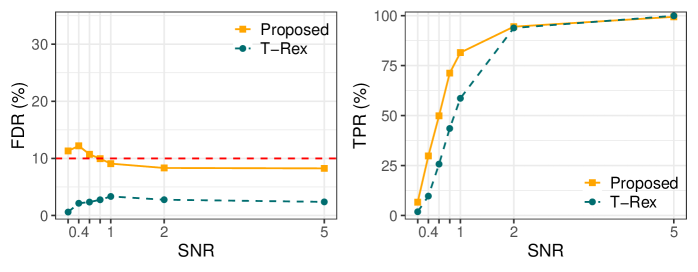

A Learned False Discovery Rate (FDR) Estimator was implemented to address accuracy limitations of the original Analytical FDP Estimator. This estimator utilizes a neural network architecture, enabling more precise FDR control, particularly in complex datasets. Evaluation on genomics data demonstrated a 2.4% increase in True Positive Rate (TPR) when employing the Learned FDP Estimator compared to the original T-Rex Selector, indicating improved statistical power and sensitivity in identifying true associations.

Effective training and validation of the Learned FDP Estimator necessitate the generation of substantial synthetic data due to the limited availability of real-world datasets with known false discovery proportions. This synthetic data is created using parameterized models that simulate various characteristics of genomic data, allowing for control over key variables influencing the FDP. The estimator is then trained on this synthetic data and its generalization performance rigorously evaluated using independent synthetic datasets. This process ensures the estimator can accurately estimate the FDP across a range of data distributions and avoid overfitting to specific characteristics of any single training set, which is crucial for reliable FDR control in downstream analyses.

Evaluation of the Learned False Discovery Rate (FDR) Estimator utilized realistic Genome-Wide Association Study (GWAS) data, generated with tools including HAPGEN2, to assess performance gains. Results indicate a True Positive Rate (TPR) of 17.3% was achieved using the Learned FDP Estimator, representing a measurable improvement over the 14.9% TPR obtained with the original T-Rex Selector when applied to the same GWAS datasets. This demonstrates the estimator’s ability to more effectively identify true positive associations within complex genomic data.

Beyond Statistical Significance: Assessing Variable Reliability

The T-Rex Selector’s reliability hinges on assessing how consistently it identifies key variables, a process quantified by ‘Relative Frequency’. This metric represents the proportion of times a specific variable appears within the selected set across numerous independent experiments. A variable repeatedly chosen signifies its potential importance, suggesting a robust association with the phenomenon under study. Calculating relative frequency allows researchers to move beyond single-instance selections and evaluate whether a variable’s prominence is a genuine characteristic or simply a result of random chance within a particular experimental run. Consequently, relative frequency serves as a crucial indicator of a variable’s true influence, providing a statistically grounded measure of its relevance within the complex system being investigated.

The composition of the final variable set, as determined by the T-Rex Selector, is intrinsically linked to the chosen ‘Voting Threshold’ parameter. This threshold acts as a selectivity control; a higher threshold demands stronger, more consistent selection across experiments before a variable is included, leading to lower relative frequencies for all but the most robustly influential factors. Conversely, a lower threshold broadens inclusion, increasing relative frequencies but potentially introducing variables with weaker, less reliable associations. Consequently, the observed relative frequencies aren’t simply a measure of inherent variable importance, but a direct reflection of this algorithmic gatekeeping, necessitating careful consideration when interpreting results and prioritizing subsequent research efforts.

A consistently high relative frequency – the rate at which a variable is selected across repeated experiments – serves as a powerful indicator of its genuine influence within a complex system. When a variable appears prominently in numerous analyses, it suggests the observed association isn’t merely due to chance or random noise. This statistical robustness allows researchers to move beyond tentative hypotheses and focus investigative efforts on these consistently identified factors. The more frequently a variable surfaces as important, the greater the confidence that it represents a true and meaningful relationship, enabling a more efficient and directed exploration of underlying biological mechanisms and accelerating the pace of scientific discovery.

By quantifying variable reliability through relative frequency, researchers gain a powerful tool for navigating the intricacies of complex biological systems. This prioritization isn’t simply about identifying any influential variable, but rather pinpointing those consistently deemed important across multiple experimental runs – a signal suggesting genuine, rather than spurious, associations. This focused approach dramatically reduces the scope of follow-up investigations, allowing resources to be concentrated on variables most likely to yield meaningful biological insights. Consequently, the method facilitates a more efficient and directed exploration of underlying mechanisms, accelerating the pace of discovery and fostering a deeper understanding of the interconnectedness within these systems.

The pursuit of statistical power, as demonstrated by this work on the T-Rex Selector and neural network calibration, reveals a fundamental truth about human endeavors. The model’s attempt to refine false Discovery Rate control isn’t a triumph of pure logic, but rather a sophisticated accounting for the inherent imperfections of estimation. As Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel observed, “We do not know truth, we only know its becoming.” This research embodies that becoming; it doesn’t discover a perfect rate, but learns to navigate the inevitable errors in high-dimensional data, striving for better approximations amidst the constant flux of uncertainty. The model, in essence, acknowledges the limits of certainty and adapts accordingly.

What’s Next?

This work, attempting to refine the identification of genuine signals amidst noise, feels less like a statistical advance and more like an exercise in applied optimism. Every hypothesis is an attempt to make uncertainty feel safe. The authors demonstrate a capacity to nudge the False Discovery Rate closer to the desired level, but the fundamental problem remains: the signals themselves are rarely as clean, or as meaningful, as the models require. The synthetic data, while useful for initial calibration, obscures the messy reality of data generated by complex, and often irrational, systems.

The true challenge isn’t better calibration, but a deeper acknowledgement of the inherent subjectivity in variable selection. Inflation is just collective anxiety about the future, and similarly, statistical significance is often a reflection of the researcher’s prior beliefs, encoded in model choices and parameter settings. Future work should focus not on minimizing false positives, but on quantifying – and perhaps even embracing – the degree of this inherent bias.

One wonders if the pursuit of ever-more-refined FDR control is a distraction. Perhaps the energy would be better spent developing methods for assigning degrees of belief to discoveries, rather than forcing a binary true/false categorization. After all, even a slightly-believed signal might prove useful, while a definitively “significant” finding can still be entirely spurious. The path forward isn’t necessarily more precision, but a more honest reckoning with the limits of knowledge.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05798.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 21 Movies Filmed in Real Abandoned Locations

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- The 11 Elden Ring: Nightreign DLC features that would surprise and delight the biggest FromSoftware fans

- 10 Hulu Originals You’re Missing Out On

- 39th Developer Notes: 2.5th Anniversary Update

- Rewriting the Future: Removing Unwanted Knowledge from AI Models

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- PLURIBUS’ Best Moments Are Also Its Smallest

- Bitcoin, USDT, and Others: Which Cryptocurrencies Work Best for Online Casinos According to ArabTopCasino

- 15 Western TV Series That Flip the Genre on Its Head

2026-02-07 22:21