Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that even advanced generative models struggle to build consistent world models, often failing to grasp the fundamental rules governing the environments they simulate.

This paper introduces an adversarial method to verify the soundness of implicit world models in generative sequence models, demonstrating a lack of causal reasoning in current systems.

Despite advances in generative sequence modeling, a fundamental question remains regarding their ability to truly capture the underlying structure of complex domains. This work, ‘Verification of the Implicit World Model in a Generative Model via Adversarial Sequences’, introduces an adversarial methodology to rigorously assess the soundness of these learned “world models” using the game of chess as a testbed. Our findings demonstrate that even models trained on extensive datasets are demonstrably unsound, failing to consistently predict valid moves, and often exhibit a disconnect between learned board state representations and actual prediction behavior. Can we develop training techniques and model architectures that move beyond mere sequence imitation toward genuine world model acquisition and robust reasoning?

Beyond Prediction: The Illusion of Understanding

For years, sequence modeling largely centered on predictive tasks – discerning the next element in a series based on preceding data. However, a shift towards more sophisticated applications, such as realistic text generation, image creation, and even code synthesis, necessitates models capable of genuine generation, not just prediction. While predicting the subsequent word in a sentence demonstrates understanding of language patterns, creating novel and coherent text demands a deeper grasp of underlying structures and relationships. This transition signifies a move beyond simply recognizing patterns to actively constructing them, requiring models to possess the capacity to invent, innovate, and produce outputs that weren’t explicitly present in the training data. The limitations of purely predictive models in tackling these increasingly complex tasks have driven the development of generative approaches, which aim to build systems capable of autonomous content creation.

Generative sequence models, exemplified by architectures such as GPT-2 and LLaMA, represent a significant leap beyond traditional sequence modeling focused solely on prediction. These models don’t simply anticipate the next element in a sequence; they actively construct new sequences, demonstrating a capacity for creative output and a more nuanced understanding of underlying data patterns. By learning the statistical relationships within vast datasets, they effectively internalize complex information, allowing them to generate text, code, or even musical compositions that exhibit coherence and originality. This capability extends beyond mere imitation, suggesting an ability to model the structure of the data itself, opening possibilities for applications ranging from automated content creation to sophisticated data augmentation and even assisting in scientific discovery by proposing novel hypotheses.

Generative sequence models don’t simply memorize training data; instead, they construct complex, internal representations of the world’s underlying structure. Through exposure to vast datasets, these models distill patterns and relationships, effectively building what can be termed ‘world models’. This isn’t a literal map, but a probabilistic understanding of how elements within the data connect and evolve – anticipating not just what comes next, but why. Consequently, the model isn’t merely predicting outputs; it’s simulating a process, drawing upon its learned internal framework to generate novel sequences that align with the implicit rules it has discovered. The sophistication of these internal representations is directly linked to the model’s capacity for creative and coherent generation, exceeding simple extrapolation and enabling nuanced responses to complex prompts.

The capacity of generative sequence models to produce remarkably coherent text stems from specialized training objectives. Rather than simply assessing a model’s accuracy, these techniques focus on its ability to predict the probability of the next element in a sequence – be it a word, a note in a melody, or a step in a robotic motion. Next Token Prediction compels the model to learn the statistical relationships within data, effectively mapping context to likely continuations. Simultaneously, Probability Distribution Prediction refines this understanding by demanding the model not just choose the most probable element, but accurately estimate the likelihood of all possible elements. This dual approach fosters a nuanced internal representation of the underlying data distribution, allowing the model to generate sequences that aren’t merely plausible, but reflect a deep grasp of the patterns and structures within the training data, ultimately leading to creative and contextually relevant outputs.

Testing the Limits: Exposing the Cracks

Soundness, in the context of sequence generation models, refers to the consistent production of valid outputs according to the defined rules of the target domain. A model exhibiting high soundness will rarely, if ever, generate sequences containing illegal or invalid elements. This property is crucial for applications requiring strict adherence to predefined constraints, as even a small percentage of invalid outputs can render the model unusable. Evaluating soundness necessitates rigorous testing methodologies capable of identifying edge cases and vulnerabilities that might lead to the generation of invalid sequences, and is often quantified by measuring the percentage of valid sequences produced across a large and diverse set of inputs.

Adversarial Sequence Generation is a testing methodology designed to evaluate the robustness of sequence generation models by actively seeking inputs that elicit invalid outputs. This process involves formulating prompts intended to ‘break’ the model, pushing it towards generating sequences that violate predefined rules or constraints. The technique differs from passive evaluation, where model performance is assessed on a standard dataset; instead, it employs algorithms to specifically maximize the probability of failure. By identifying these adversarial inputs, developers can pinpoint vulnerabilities and improve model soundness, ensuring consistent and valid sequence generation across a wider range of conditions.

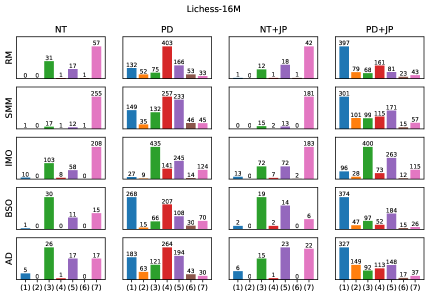

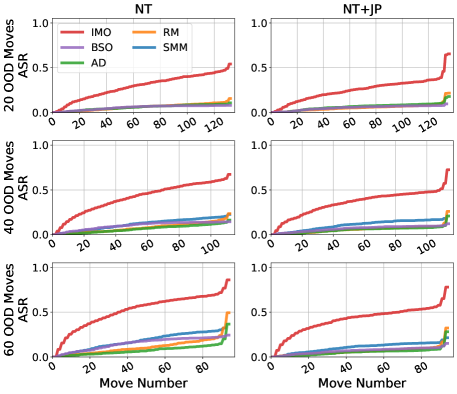

Adversarial sequence generation employs techniques such as the Illegal Move Oracle to identify inputs specifically designed to elicit invalid outputs from language models. This Oracle functions by iteratively searching for input sequences that maximize the probability of an illegal continuation, as defined by the rules of the environment – in contexts like game playing, this means generating moves that violate legal game rules. Testing has demonstrated a 100% Attack Success Rate (ASR) against several models when utilizing this method, indicating a consistent ability to force the generation of invalid sequences through targeted input construction. The ASR metric quantifies the proportion of attempts where the model produces an illegal continuation given an adversarial input.

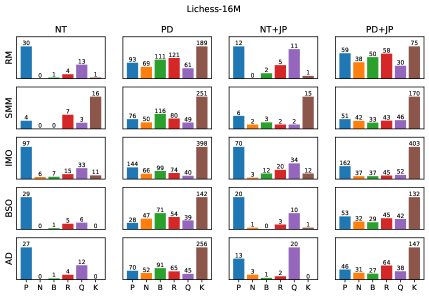

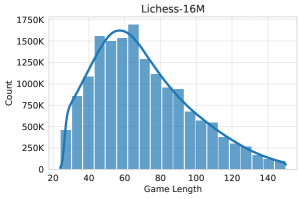

Chess provides a robust environment for evaluating sequence generation models due to its deterministic rules and unambiguous validity criteria; any move not conforming to these rules is immediately identifiable as invalid. This allows for quantitative assessment of a model’s ‘Soundness’ – its capacity to consistently produce legal sequences. Input and output moves are standardized using Universal Chess Interface (UCI) notation, a widely adopted protocol that facilitates automated testing and comparison across different chess engines and models. The clear delineation between valid and invalid states, combined with the structured data format of UCI, allows for the creation of automated ‘Illegal Move Oracles’ to efficiently identify inputs that maximize the probability of generating an illegal continuation.

Decoding Strategies and the Illusion of Control

The characteristics of generated sequences in language models are fundamentally determined by the interplay between training data and the decoding strategy utilized. Training on curated datasets, typically composed of high-quality examples demonstrating desired behaviors, tends to yield outputs prioritizing correctness and adherence to established patterns. Conversely, training on broader, randomly generated datasets encourages exploration of a wider solution space, potentially increasing diversity but also introducing a higher risk of suboptimal or invalid sequences. The decoding strategy then governs how the model samples from its learned probability distribution; methods like Top-k or Top-p sampling modulate the balance between exploiting high-probability tokens and exploring lower-probability alternatives, directly impacting both the coherence and novelty of the generated output.

Training datasets for sequence generation models commonly fall into two categories: curated and random. Curated datasets consist of sequences derived from expert demonstrations – for example, game play recorded from skilled players – and prioritize high-quality, strategically sound examples. Random datasets, conversely, are generated through stochastic processes, creating a wider, though potentially less optimal, distribution of states and actions. The choice between these approaches impacts model behavior; curated datasets can lead to imitation of expert strategies, while random datasets encourage exploration of a larger state space, potentially uncovering novel, albeit less conventional, solutions. The composition of the training data directly affects the model’s learned policy and its subsequent performance characteristics.

Achieving a high Legal Move Ratio, ranging from 94.65% to 99.98% in evaluated models, indicates proficiency in generating syntactically valid actions within the rules of the game but provides limited insight into the model’s understanding of the underlying game state or long-term strategic implications. This metric assesses only the immediate legality of a move and does not correlate with the model possessing a robust or accurate internal representation of the game world, causal relationships, or the consequences of its actions beyond the immediate turn. Consequently, a high Legal Move Ratio should not be interpreted as evidence of genuine intelligence or strategic depth; it merely confirms the model’s ability to adhere to the defined rule set.

Top-k Sampling and Top-p (nucleus) Sampling are decoding strategies used to introduce variability into sequence generation while maintaining coherence. Top-k Sampling restricts the next-token selection to the k most probable tokens, preventing low-probability, potentially nonsensical outputs. Top-p Sampling, conversely, dynamically selects the smallest set of tokens whose cumulative probability exceeds a probability p, allowing for a more adaptive selection range. Both methods balance exploration – generating diverse outputs – and exploitation – favoring high-probability continuations. The parameter values for k and p directly influence this balance; lower values encourage exploitation and higher values promote exploration, affecting the overall diversity and quality of the generated sequence.

Probing the Void: What Does It Mean to “Understand”?

Determining whether an artificial intelligence truly understands a task requires more than simply evaluating its performance; a focus on internal representations is crucial. While observable outputs demonstrate a model’s ability to produce correct answers, they offer limited insight into how those answers are generated. A system might excel at predicting outcomes without possessing a coherent, structured understanding of the underlying principles governing those outcomes. Therefore, researchers are increasingly turning to methods that directly examine the information encoded within the model itself-essentially, peering into its “mind” to assess if it has constructed a meaningful and accurate representation of the world, rather than merely memorizing patterns in the data. This shift in focus allows for a deeper evaluation of genuine comprehension, moving beyond superficial success to uncover the quality of the model’s internal world model.

The Board State Probe offers a novel method for dissecting the “black box” of complex AI models by attempting to reconstruct the game board’s configuration directly from the model’s internal data representations. This technique functions by training a separate predictive model – the probe – to decode the information encoded within a specific layer of the AI’s neural network. If the probe can accurately predict the board state – the positions of pieces, for instance – it suggests that the AI itself has implicitly learned and stored a representation of that state within its internal structure. Essentially, the probe acts as an interpreter, revealing what information the AI deems relevant to its decision-making process and how that information is organized, offering valuable insights into the model’s underlying understanding of the game environment.

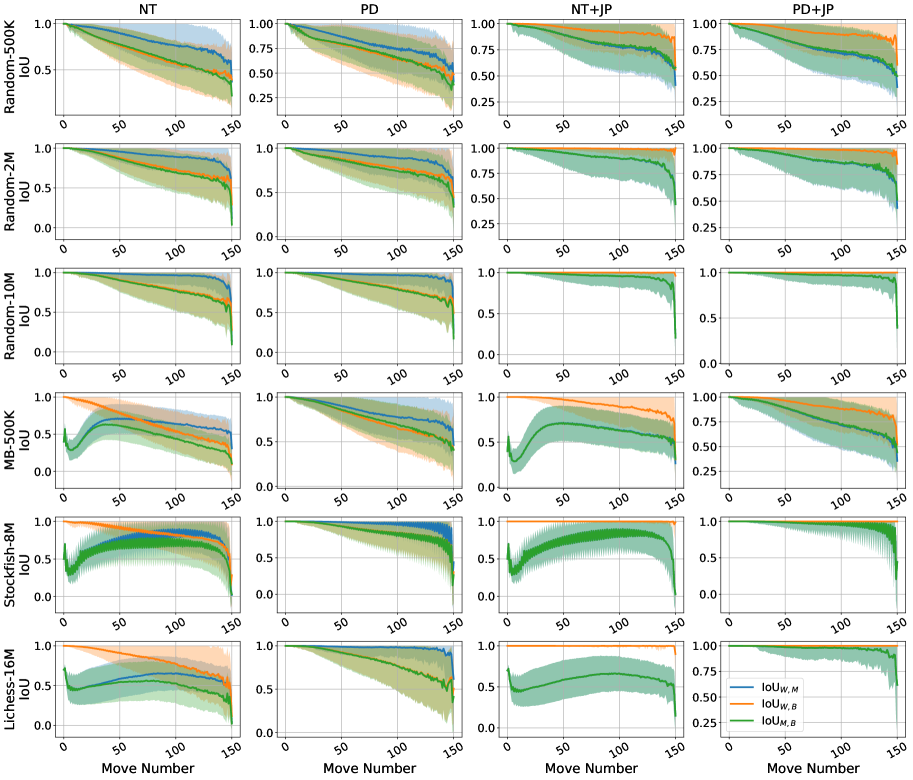

Investigations into the alignment between a model’s internal representations and the true state of the world, as measured by Intersection over Union (IoU), reveal a nuanced relationship between probing performance and the development of robust internal world models. While a model might successfully predict board states via a high-performing probe, variations in IoU scores based on different training methodologies suggest that this predictive capability doesn’t automatically guarantee a genuine understanding of the underlying environment. Specifically, certain training approaches can prioritize superficial pattern matching sufficient for accurate probing, without necessarily fostering a comprehensive and reliable internal representation of the world’s causal structure. This indicates that a model can appear to understand through successful probing, even if its internal model lacks the robustness needed for generalization or adaptation to novel situations, highlighting the importance of evaluating internal representations beyond simple predictive accuracy.

When a model successfully passes the Board State Probe – accurately predicting the game state from its internal data – it indicates more than just pattern recognition; it suggests the development of an implicit world model. This internal representation isn’t a conscious, explicitly programmed understanding, but rather an emergent ability to encode and reason about the environment. The model effectively builds a compressed, internal ‘simulation’ of the game, allowing it to anticipate consequences and plan actions based on its understanding of the relationships between objects and their potential states. This capability transcends simply learning to map inputs to outputs; it demonstrates a form of environmental understanding, crucial for generalization and robust performance in novel situations. The presence of such a model hints at a deeper level of intelligence, moving beyond superficial competence towards genuine comprehension of the underlying dynamics.

The pursuit of robust generative sequence models, as detailed in this paper, feels predictably Sisyphean. Researchers strive for models possessing sound implicit world models, yet the adversarial sequences demonstrate a fragility inherent in these systems. It’s almost quaint. Donald Davies, a pioneer of packet switching, observed that “a system is only as good as its weakest link,” and this rings true. These models, despite their complexity and training data, repeatedly fail basic causality checks. One begins to suspect ‘world model’ is just a fancy term for ‘elaborate guess,’ and the adversarial testing simply exposes the inevitable cracks. It’s the same mess, just more expensive, really. At least the failures are consistent, offering some predictability for the digital archaeologists who will inevitably dissect this work.

What’s Next?

The exercise of probing for soundness in these generative systems reveals, predictably, a gap between fluency and understanding. The models generate sequences; they do not, it seems, know anything about the worlds they simulate. The bug tracker is filling up with adversarial examples, each one a tiny indictment of the assumption that scale alone breeds intelligence. The current focus on ever-larger datasets feels less like progress and more like delaying the inevitable confrontation with fundamental limitations.

Future work will undoubtedly involve more sophisticated probing techniques, and attempts to inject causality through architectural constraints. But the deeper issue isn’t simply how to build a sound model, it’s whether the current paradigm – training on correlation alone – can ever truly capture the complexities of even a relatively simple domain like chess. The models learn to predict the next token; they don’t learn cause and effect.

The research field will cycle through increasingly elaborate verification schemes, each one temporarily raising the bar before being circumvented by a cleverly crafted adversarial sequence. It’s a Sisyphean task, but one that exposes the core fallacy: that a convincing imitation of intelligence is, in itself, intelligence. The models don’t deploy – they let go.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05903.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 21 Movies Filmed in Real Abandoned Locations

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- The 11 Elden Ring: Nightreign DLC features that would surprise and delight the biggest FromSoftware fans

- 39th Developer Notes: 2.5th Anniversary Update

- 10 Hulu Originals You’re Missing Out On

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Rewriting the Future: Removing Unwanted Knowledge from AI Models

- 15 Western TV Series That Flip the Genre on Its Head

- PLURIBUS’ Best Moments Are Also Its Smallest

- Leaked Set Footage Offers First Look at “Legend of Zelda” Live-Action Film

2026-02-07 19:00