Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new approach leverages the power of transformer models to directly predict solutions for discrete optimization problems, sidestepping the need for traditional inverse optimization techniques.

This work introduces a structured prediction framework utilizing transformer models and constraint reasoning for data-driven combinatorial optimization.

Addressing combinatorial optimization problems with unknown components often relies on computationally expensive inverse optimization techniques. This paper, ‘Inverse Optimization Without Inverse Optimization: Direct Solution Prediction with Transformer Models’, introduces a novel framework leveraging transformer models and constraint reasoning to directly predict solutions from past data. The approach yields remarkably strong performance and scalability across problems like knapsack, bipartite matching, and scheduling, consistently generating near-optimal solutions in a fraction of a second. Could this data-driven paradigm offer a viable alternative to traditional optimization methods, particularly when dealing with complex and implicit constraints?

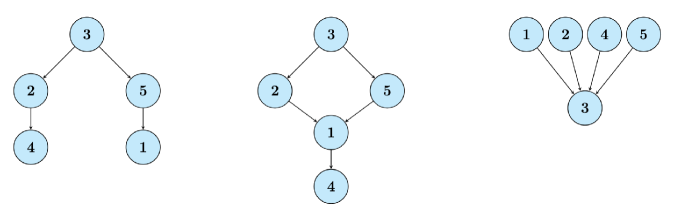

The Geometry of Choice: Defining Discrete Optimization

The seemingly disparate challenges of modern life – efficiently routing delivery trucks, scheduling airline crews, or allocating limited hospital resources – are often manifestations of a single underlying mathematical problem: discrete optimization. These scenarios aren’t about finding the best value along a continuous spectrum, but rather selecting the optimal combination from a finite, and often vast, set of possibilities. Each decision involves choosing from distinct options – a specific route, a particular crew member, a designated operating room – creating a combinatorial landscape where the number of potential solutions grows exponentially with the problem’s size. This fundamental characteristic defines discrete optimization and differentiates it from continuous optimization, demanding specialized algorithms and approaches to navigate the complex search space and arrive at practical, effective solutions.

The inherent difficulty in solving discrete optimization problems stems from what is known as combinatorial explosion – a rapid growth in the number of possible solutions as the problem’s size increases. Consider a seemingly simple task like scheduling deliveries; adding even a few more stops drastically multiplies the number of potential routes. Traditional algorithms, while effective for smaller instances, quickly become overwhelmed by this exponential increase in complexity, demanding computational resources that scale prohibitively. This limitation hinders their adaptability to real-world scenarios characterized by dynamic changes and large datasets. Consequently, these methods struggle to find optimal, or even reasonably good, solutions within practical timeframes, necessitating the development of novel approaches capable of navigating this vast solution space efficiently.

Predicting Structure: A Data-Driven Synthesis

Structured prediction differs from traditional machine learning approaches by directly learning a mapping from input variables, denoted as x, to a complete solution, represented as y. Rather than predicting individual elements of y independently, structured prediction models consider the dependencies between these elements and output the entire solution structure at once. This is achieved through algorithms that optimize a loss function measuring the discrepancy between predicted and true solution structures. Consequently, the model learns to predict the optimal y given x, circumventing the need for separate decoding or search procedures typically required to construct a solution from individual predictions. Examples include sequence labeling, parsing, and machine translation, where the relationships between output elements are crucial for accuracy.

Structured prediction utilizes labeled datasets to learn the relationships between input features and corresponding optimal outputs. By training on historical data, the system identifies recurring patterns and establishes a probabilistic model that maps new, unseen instances to likely solutions. This contrasts with traditional methods that often require exhaustive search through a solution space, as the learned model directly predicts the entire output structure, reducing computational cost and enabling generalization to previously unencountered scenarios. The efficacy of this approach relies on the quantity and quality of the training data and the model’s capacity to represent the underlying dependencies within the data.

The performance of structured prediction models is directly contingent on the selected architectural design and its capacity to model intricate relationships within the data. Effective architectures must accurately represent the dependencies between input features and output elements, allowing the model to generalize beyond the training data. This often involves utilizing specific network layers – such as conditional random fields (CRFs), recurrent neural networks (RNNs), or transformers – capable of capturing sequential or hierarchical information. The complexity of the architecture should be commensurate with the complexity of the dependencies present in the data; insufficient architectural capacity may lead to underfitting, while excessive complexity can result in overfitting and reduced generalization performance. Careful consideration of these dependencies during architectural design is crucial for achieving optimal predictive accuracy.

Constraining the Search: Validity Through Deterministic Systems

Solution feasibility is a critical component of problem-solving beyond simply identifying a potential answer. A predicted solution must adhere to all explicitly defined constraints of the problem space to be considered valid. These constraints represent the limitations or rules governing acceptable outcomes; failure to satisfy even one constraint renders the solution unusable. Consequently, a system capable of generating solutions must incorporate a mechanism to verify constraint satisfaction, preventing the output of invalid or impractical results, regardless of predictive accuracy. This verification step is distinct from, and equally important as, the solution prediction itself.

DFA-based constraint reasoning operates by representing possible solution states as nodes within a Deterministic Finite Automaton (DFA). Constraints are encoded as transitions between these states; a transition is only permitted if the proposed solution component satisfies all applicable constraints. During the prediction process, the system traverses the DFA, effectively building a solution incrementally while simultaneously verifying constraint adherence at each step. If a transition is unavailable due to a constraint violation, that solution path is immediately discarded, guaranteeing that only valid solutions-those satisfying all predefined constraints-are considered. This approach avoids generating infeasible solutions, thereby increasing efficiency and ensuring the reliability of the final result.

DFA-based constraint reasoning exhibits increased efficiency when applied to problems characterized by monotone constraint systems. In these systems, the addition of a new solution does not necessitate the removal or invalidation of any previously identified solutions; constraints are only added as the search progresses. This property allows for incremental validation and avoids the need to re-evaluate the feasibility of existing solutions with each new finding, significantly reducing computational complexity and improving performance compared to scenarios involving non-monotone constraints where backtracking and re-evaluation are frequent necessities.

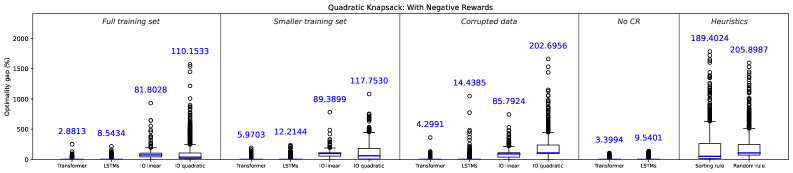

Beyond Simplification: Embracing Complex Objectives

Optimization problems frequently present simplified, linear objectives for ease of solution, yet the challenges of the real world rarely conform to such neatness. Many practical scenarios – from resource allocation and logistical planning to financial modeling and machine learning – involve quadratic, polynomial, or even more intricate objective functions. These complexities arise from factors like diminishing returns, interactions between variables, or non-linear relationships inherent in the system being optimized. Consequently, algorithms designed solely for linear optimization often struggle to find truly optimal – or even reasonably good – solutions in these realistic settings, necessitating more sophisticated approaches capable of navigating these non-linear landscapes and accurately reflecting the underlying problem structure.

The architecture’s adaptability stems from its integration of constraint reasoning with a structured prediction framework. Rather than relying on simplifying assumptions of linearity, the system can accommodate quadratic and higher-order objective functions commonly found in practical optimization challenges. This is achieved by encoding problem-specific constraints – limitations on feasible solutions – directly into the prediction process, guiding the model toward valid and increasingly optimal outcomes. Consequently, the framework doesn’t merely search for solutions; it constructs them by intelligently adhering to defined boundaries, which is particularly advantageous when dealing with the inherent complexities of real-world scenarios where simple linear models often fall short.

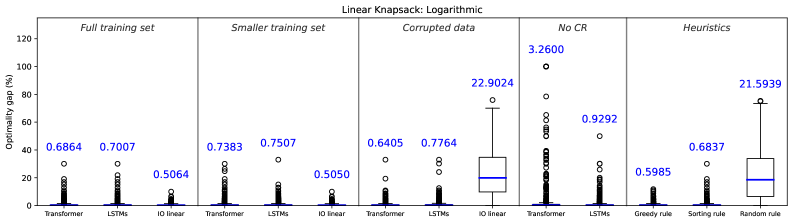

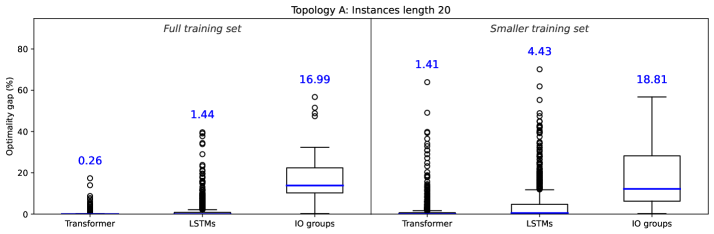

Evaluations across three distinct combinatorial optimization challenges – the knapsack problem, bipartite matching, and job-shop scheduling – demonstrate the superior performance of the proposed transformer-based structured prediction approach. Compared to both Inverse Optimization (IO) techniques and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks, this method consistently achieves lower optimality gaps, indicating solutions closer to the true optimum. This consistent improvement suggests the transformer architecture’s ability to effectively capture complex dependencies within these problems, allowing for more accurate predictions of optimal structures and ultimately leading to enhanced solution quality. The results highlight the potential of this framework to tackle real-world optimization tasks where near-optimal solutions are critical and traditional methods struggle with complexity.

The Architecture of Insight: A Transformer-Based Future

Structured prediction tasks, which involve forecasting multiple interconnected variables, often struggle with capturing the intricate relationships within the data. Integrating the Transformer architecture addresses this challenge by moving beyond sequential processing limitations. Unlike recurrent models, Transformers utilize self-attention, enabling the model to directly assess the influence of every input element on every other, regardless of their distance. This capability is particularly crucial in scenarios where long-range dependencies are prevalent, such as in complex scheduling or resource allocation problems. By modeling these relationships more effectively, the Transformer-based approach unlocks superior performance in predicting structured outputs and offers a robust framework for tackling problems where the interconnectedness of variables is paramount.

The core of this advancement lies in the Transformer’s self-attention mechanism, which fundamentally alters how the model processes input data. Unlike traditional sequential models, self-attention doesn’t prioritize information based on its position; instead, it dynamically weighs the importance of each input element relative to all others. This allows the model to directly capture long-range dependencies and contextual relationships, focusing computational resources on the most relevant parts of the problem. Consequently, solutions are not only more accurate, as the model avoids being misled by irrelevant details, but also more efficient, as unnecessary computations are minimized. By intelligently prioritizing information, the model achieves a deeper understanding of the input structure, ultimately leading to improved performance across various structured prediction tasks.

Recent advancements in structured prediction consistently demonstrate that a Transformer-based approach surpasses both Integer Optimization (IO) and Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM) networks in both the quality of solutions generated and the speed at which they are found. Across a diverse range of applications, this methodology achieves markedly higher feasibility rates, indicating a greater capacity to produce valid and practical outcomes. Notably, within complex scheduling problems, the system attains over 90% precedence satisfaction – a substantial improvement compared to traditional IO methods, which struggle to meet the same criteria. This enhanced performance stems from the Transformer’s ability to efficiently model intricate relationships within the data, leading to more robust and effective predictions and ultimately offering a compelling advantage in tackling complex structured prediction tasks.

The pursuit of direct solution prediction, as detailed in the paper, mirrors a fundamental simplification. It eschews the iterative refinement of inverse optimization for a singular, predictive leap. This aligns with a preference for structural honesty; the model doesn’t attempt to reconstruct an optimal solution, but to directly manifest it. As Grigori Perelman once stated, “Everything is simple, but everything is also complicated.” The paper embodies this sentiment by addressing the complexity of combinatorial optimization through a streamlined transformer architecture, prioritizing clarity of prediction over convoluted reconstruction-a testament to the beauty found in reductive design. The core concept of constraint reasoning within the framework reinforces this elegance, distilling problems to their essential elements.

Where To Next?

This work sidesteps inverse optimization’s inherent recursion. It predicts directly. A useful trick, certainly. But prediction, absent understanding, remains brittle. The model excels with known constraints. The true test lies in generalizing to unseen problem structures. That challenge persists.

Current approaches treat constraints as fixed inputs. Yet, real-world optimization frequently involves evolving constraints. Future work must address this dynamic element. Furthermore, interpretability remains elusive. Abstractions age, principles don’t. Knowing what the model predicts is insufficient. Understanding why is paramount.

The promise of scaling constraint reasoning via transformers is clear. However, every complexity needs an alibi. Simply increasing model size isn’t a solution. The field needs more than clever architectures. It needs foundational principles. A theory of constraint representation-one that marries symbolic reasoning with learned representations-remains the ultimate goal.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2602.05306.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 21 Movies Filmed in Real Abandoned Locations

- The 11 Elden Ring: Nightreign DLC features that would surprise and delight the biggest FromSoftware fans

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- 10 Hulu Originals You’re Missing Out On

- Gold Rate Forecast

- PLURIBUS’ Best Moments Are Also Its Smallest

- 39th Developer Notes: 2.5th Anniversary Update

- Top ETFs for Now: A Portfolio Manager’s Wry Take

- Bitcoin, USDT, and Others: Which Cryptocurrencies Work Best for Online Casinos According to ArabTopCasino

- Ethereum’s P2P Overhaul: Vitalik Buterin’s ‘Heroic’ Fix 🚀 or a Cry for Help? 💸

2026-02-07 02:25