Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a new method to extract meaningful spectral representations from neural networks, moving beyond ‘black box’ predictions to reveal the underlying mechanisms.

This work presents a framework for discovering interpretable spectral kernels from Prior-Data Fitted Networks (PFNs) without iterative optimization, bridging the gap between predictive performance and mechanistic understanding.

While Prior-Data Fitted Networks (PFNs) excel at efficient probabilistic modeling, their learned priors and resulting kernel structures remain largely opaque. This work, ‘Amortized Spectral Kernel Discovery via Prior-Data Fitted Network’, introduces a framework to interpret and extract explicit spectral representations from pre-trained PFNs, revealing the connection between latent outputs and underlying function covariance. By leveraging Bochner’s theorem, we demonstrate how to map PFN latents to spectral density estimates and corresponding stationary kernels, enabling accurate Gaussian process regression with significantly reduced inference time. Could this approach unlock a new level of mechanistic understanding and practical utility for amortized inference in complex systems?

The Inevitable Decay: Quantifying Uncertainty in Prediction

Many conventional machine learning models prioritize predictive accuracy without explicitly estimating the confidence in those predictions. This omission is a critical limitation, as a seemingly accurate point prediction is often insufficient for informed decision-making, particularly in high-stakes applications like medical diagnosis or financial modeling. Without quantifying uncertainty – understanding the range of plausible outcomes – it becomes difficult to assess the risk associated with a prediction and to reliably differentiate between genuine signals and random noise. Consequently, models lacking explicit uncertainty quantification can lead to overconfident, yet incorrect, conclusions, hindering their practical utility and potentially leading to costly errors. The ability to express not just what a model predicts, but also how sure it is, represents a significant advancement toward more robust and trustworthy artificial intelligence.

Gaussian Processes represent a robust method for modeling functions and quantifying uncertainty in predictions, differing from many machine learning approaches that offer only point estimates. However, the very strength of this probabilistic framework comes at a computational price; traditional Gaussian Process implementations require calculations that scale cubically with the number of data points, denoted as O(n^3). This steep scaling limits their applicability to relatively small datasets, creating a significant bottleneck when dealing with the large-scale problems common in modern data science. The core issue stems from the need to invert the covariance matrix, a computationally expensive operation, and this limitation has driven research into methods for approximating or efficiently representing Gaussian Processes to unlock their potential for larger, more complex datasets.

The computational burden of Gaussian Processes, while powerful for probabilistic modeling, stems from operations that scale poorly with dataset size. A key innovation addresses this through spectral representations, which decompose the kernel function – the heart of a Gaussian Process – into its constituent frequencies. This decomposition, known as the spectral density, allows for computations to be performed in the frequency domain, often leveraging the Fast Fourier Transform for significant speedups. Moreover, examining the spectral density provides valuable insights into the characteristics of the kernel and, consequently, the underlying function being modeled; peaks in the spectral density, for example, indicate dominant frequencies or periodicities. By shifting the focus from the original input space to the spectral domain, researchers gain both computational efficiency and a more interpretable understanding of the Gaussian Process model, opening doors to applications with larger datasets and more nuanced analyses.

Adapting to the Flow: Learning Kernels from Data

Deep Kernel Learning (DKL) addresses limitations of static kernels by constructing kernels directly from data through iterative optimization processes. Unlike traditional kernel methods which rely on pre-defined kernels, DKL employs parameterized functions-typically neural networks-to map data into a feature space where a kernel can be implicitly defined. The parameters of these networks are then adjusted via gradient descent or similar optimization algorithms to maximize performance on a given task. This data-dependent approach allows the kernel to adapt to the specific characteristics of the dataset, potentially capturing complex relationships that would be missed by a fixed kernel. The optimization objective typically incorporates a regularization term to prevent overfitting and ensure generalization to unseen data.

Kernel Reconstruction is a core component of Deep Kernel Learning, enabling the creation of kernels directly from their spectral densities. This process leverages Bochner’s Theorem, which establishes a bijective relationship between a positive definite kernel function k(x, x') and its characteristic frequency function, or spectral density \Phi(\omega) . Specifically, Bochner’s Theorem states that a continuous, symmetric function k(x) is a positive definite kernel if and only if its Fourier transform, \Phi(\omega) , is non-negative. By defining a desired spectral density and then performing an inverse Fourier transform, a corresponding kernel function can be explicitly constructed, offering a method for kernel design based on frequency domain characteristics.

Transforming kernel learning problems into the frequency domain – specifically, analyzing the kernel’s spectral density – allows for a decomposition of the data based on its constituent frequencies. This frequency-based representation reveals inherent data structure, such as dominant periodicities or the distribution of variances across different scales. Consequently, kernel design becomes more efficient as optimization can be performed on the spectral density directly, often leading to closed-form solutions or simplified iterative procedures. Analyzing the spectral density also facilitates the identification of appropriate kernel parameters, enabling the creation of kernels tailored to the specific characteristics of the data and potentially reducing computational complexity compared to optimization in the original data space.

Beyond Static Forms: Embracing Non-Stationary Complexity

Stationary kernel functions, defined by their translational invariance – meaning the kernel’s value depends only on the distance between data points, not their absolute location – offer computational benefits in machine learning models like Gaussian Processes. However, this very property limits their ability to effectively model non-stationary data common in real-world applications. Specifically, stationary kernels assume consistent relationships across the entire input space, failing to capture localized variations or directional dependencies. This inflexibility manifests as poor performance when dealing with data exhibiting differing characteristics across different regions or with features that interact in a non-uniform manner, necessitating the use of more complex, non-stationary kernel approaches to achieve accurate modeling.

Spectral Mixture Kernels (SMKs) address limitations of stationary kernels by constructing a kernel function as a weighted sum of Gaussian functions in the frequency domain. Unlike stationary kernels which assume a single spectral density, SMKs model the spectral density as a mixture of Gaussian distributions \sum_{i=1}^{K} w_i N(\mu_i, \Sigma_i) , where K represents the number of Gaussian components, w_i are the weights, and N(\mu_i, \Sigma_i) denotes a Gaussian distribution with mean \mu_i and covariance \Sigma_i . This allows SMKs to represent a broader range of spectral shapes and capture non-stationary characteristics in the data by effectively modeling variations in frequency-domain energy distribution. The kernel function is then constructed by taking the inverse Fourier transform of this spectral mixture.

Additive Gaussian Process (GP) models increase model flexibility by representing a function as the sum of multiple independent GP components, each potentially operating on a different subset of input dimensions or feature spaces. This decomposition allows the model to capture complex, non-additive interactions between variables that a single GP kernel would struggle to represent. Specifically, given K(x, x') as the covariance function of a standard GP, an additive GP defines a new covariance function as K_{additive}(x, x') = \sum_{i=1}^{n} K_i(x, x'), where K_i represents the covariance function of the i-th GP component. Each K_i can utilize different kernel parameters or even different kernel types, allowing for specialized modeling of specific input features or interactions. This approach effectively increases the model’s capacity to represent complex relationships without necessarily increasing computational cost proportionally, as inference can often be performed by summing the predictions from each individual GP component.

Distilling Essence: Decoding Spectral Representations for Efficient Inference

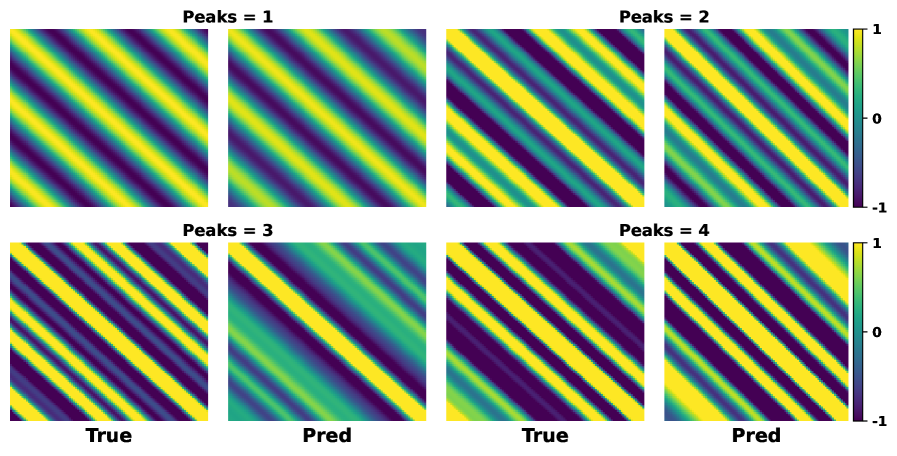

The Filter Bank Decoder offers a novel approach to utilizing pre-trained neural networks for inference by explicitly extracting the spectral densities embedded within their frozen weights. This process transforms the network into a functional form, revealing how it processes information across different frequencies and allowing for a more transparent understanding of its internal representations. Instead of relying on computationally expensive forward passes through the entire network, the decoder distills the essential spectral information, enabling predictions to be generated with significantly reduced computational cost. The resulting spectral representation not only accelerates inference but also provides a means of interpreting the network’s behavior, bridging the gap between complex deep learning models and more interpretable statistical methods like Gaussian processes.

The decoder architecture employs Multi-Query Attention, a technique designed to drastically reduce computational demands during the extraction of latent representations from frozen neural networks. Traditional attention mechanisms require calculating attention weights for every query-key pair, creating a significant bottleneck, particularly with high-dimensional data. Multi-Query Attention cleverly shares the key and value projections across all queries, effectively decreasing the computational cost while preserving representational capacity. This sharing strategy allows the decoder to efficiently process information without sacrificing accuracy, resulting in a substantial reduction in both memory usage and processing time. The innovation enables faster inference without the need for retraining or modifying the original neural network, making it a practical solution for resource-constrained environments and real-time applications.

The innovative Decoupled-Value Attention mechanism establishes a compelling link between deep learning and Gaussian Process (GP) regression by structurally mirroring the GP update rule. Traditional attention mechanisms compute a weighted sum of values based on query-key similarity; however, this approach lacks a direct correspondence to Bayesian inference. Decoupled-Value Attention, in contrast, explicitly separates the computation of attention weights from the aggregation of values, allowing the network to learn a representation that closely resembles the posterior mean and variance update steps in a GP. This architectural alignment isn’t merely theoretical; it enables the model to perform inference in a manner consistent with probabilistic reasoning, potentially improving generalization and uncertainty estimation, while also providing a clear interpretation of the learned representations in terms of established Bayesian principles. The resulting framework allows for a more principled understanding of attention mechanisms and facilitates the transfer of theoretical insights from Gaussian Processes to deep neural networks.

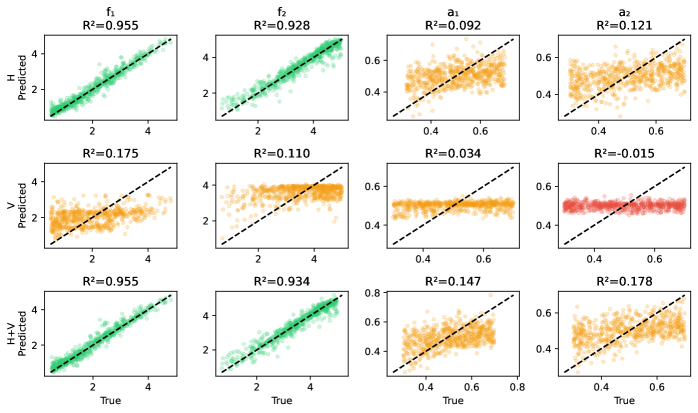

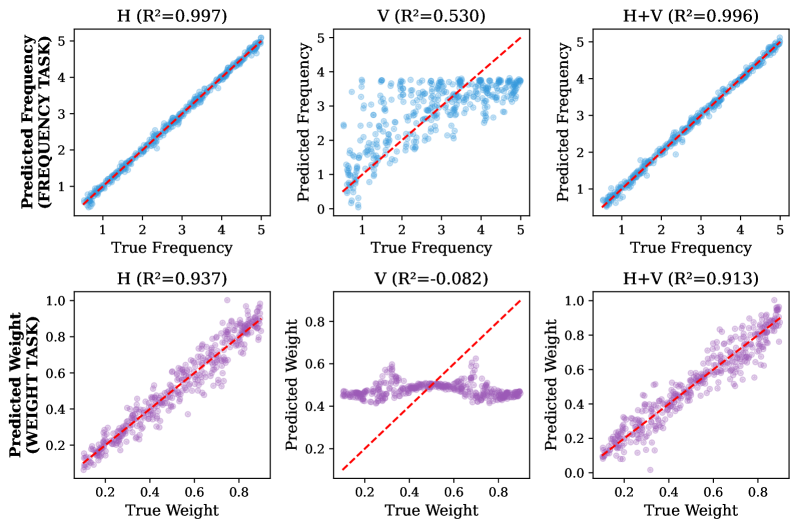

The proposed framework demonstrates a substantial leap in inference efficiency, achieving speedups of roughly three orders of magnitude when contrasted with established kernel optimization techniques like DKL and RFF. This acceleration doesn’t come at the expense of accuracy; rigorous evaluation on the Kernel Cookbook benchmark reveals performance comparable to highly optimized Gaussian processes. Such a significant reduction in computational demands opens possibilities for deploying complex kernel methods in resource-constrained environments and scaling them to larger datasets, effectively bridging the gap between theoretical power and practical application. The ability to achieve comparable results with dramatically reduced computation represents a key advancement in the field of machine learning inference.

The Horizon of Understanding: Data Requirements and the Limits of Identifiability

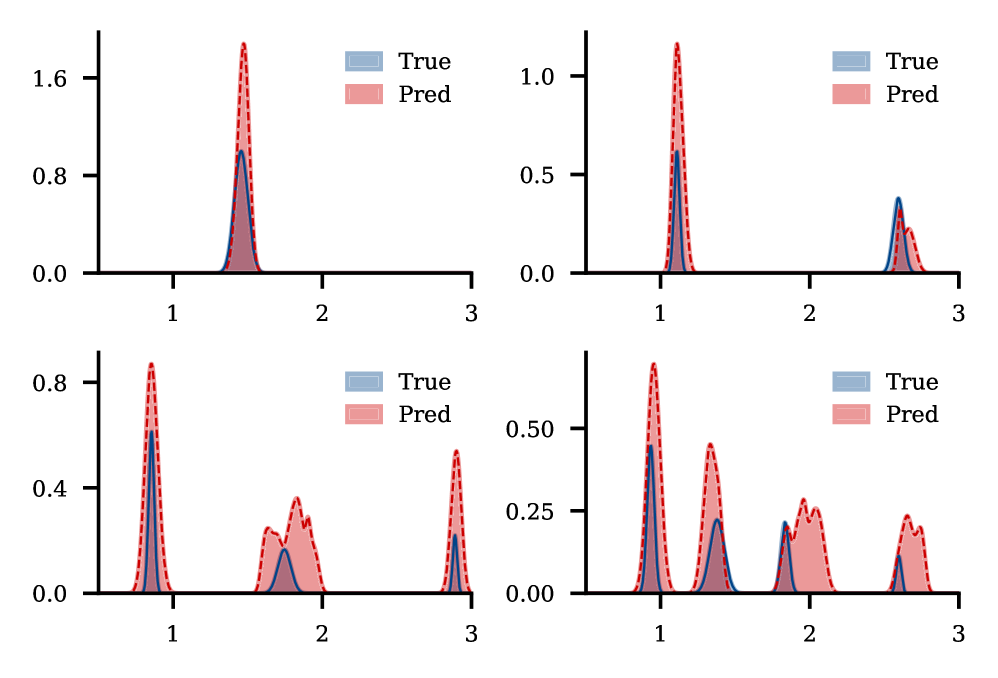

Statistical identifiability faces inherent limitations when relying on a single realization of a random process, posing significant challenges to accurate spectral estimation. This constraint arises because a single observation provides insufficient information to uniquely determine the underlying probability distribution governing the process; numerous spectral densities could plausibly generate the observed data. Consequently, estimates derived from single realizations are prone to substantial uncertainty and may exhibit considerable deviation from the true spectrum. The difficulty isn’t simply one of computational precision, but a fundamental limitation imposed by the data itself – a single sample inherently lacks the power to resolve the complexities of the underlying spectral structure. This necessitates careful consideration of model assumptions and the potential for overfitting, and motivates the exploration of methodologies leveraging multiple independent observations to enhance the reliability and accuracy of spectral estimates.

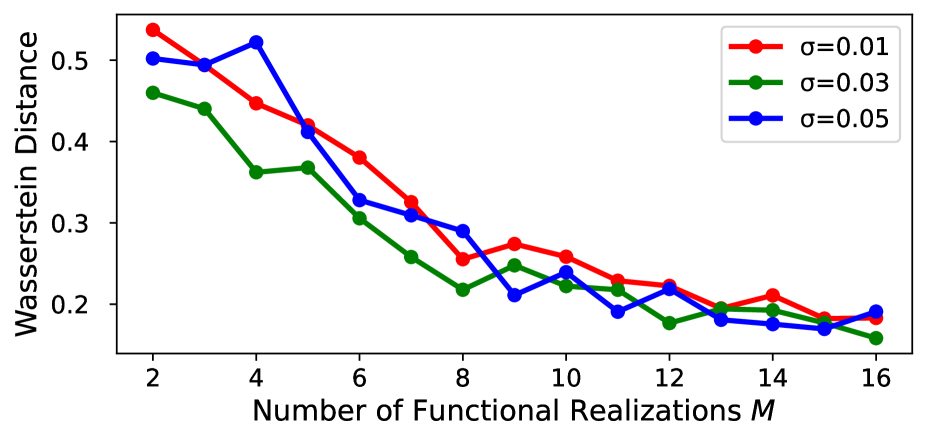

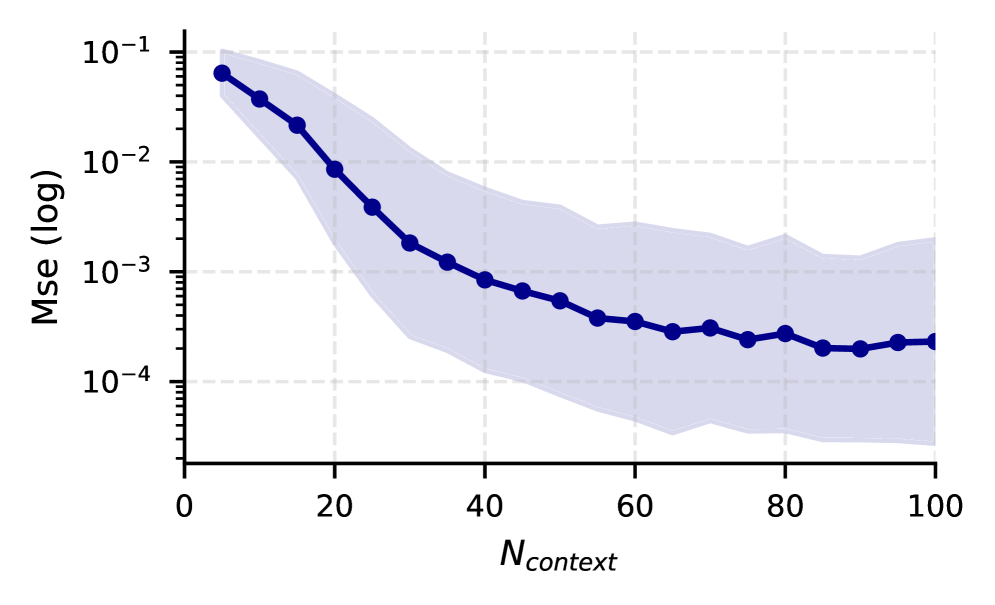

Statistical identifiability, the capacity to uniquely determine a model’s parameters from observed data, is fundamentally enhanced when transitioning from a single realization to a multi-realization setting. Acquiring multiple, independent observations allows for a more robust estimation of underlying spectral densities, mitigating the inherent limitations imposed by single datasets. This improvement stems from the ability to average out random fluctuations and noise, leading to a clearer signal and a more accurate representation of the true spectral characteristics. Consequently, model reliability increases substantially; predictions become less sensitive to individual data points and more representative of the general underlying process, enabling confident inference and informed decision-making based on spectral analysis.

This analytical framework demonstrates a remarkable capacity for accurate Gaussian Process (GP) regression, achieving a Mean Squared Error (MSE) that is statistically comparable to that of an “Oracle GP”-a theoretical ideal with complete knowledge of the underlying data. Crucially, this high level of performance is sustained even when dealing with datasets in 10-dimensional spaces, where performance typically degrades. The framework maintains results within 10-15% of the Oracle GP’s accuracy in these higher dimensions, signifying its robustness and scalability for complex data analysis.

Analysis reveals a consistent convergence of predicted spectral densities towards the true underlying distribution as the number of Gaussian process (GP) samples increases. Quantified using the Wasserstein distance – a metric measuring the ‘distance’ between probability distributions – the study demonstrates a monotonically decreasing trend; that is, with each additional GP sample, the predicted spectral density consistently moves closer to the ground truth. This behavior confirms the asymptotic consistency of the proposed framework, indicating that, given sufficient data, the model reliably approximates the true spectral characteristics of the observed phenomena. The decreasing Wasserstein distance serves as a powerful validation tool, demonstrating the model’s capacity to refine its predictions and converge toward accurate spectral estimation with increasing data availability.

Advancing spectral modeling necessitates focused innovation in data-efficient estimation techniques. Current methodologies often demand substantial datasets to achieve reliable performance, limiting their applicability in scenarios where data acquisition is costly or constrained. Future research should prioritize the development of robust algorithms capable of accurately reconstructing spectral densities from limited observations, potentially leveraging techniques like transfer learning, meta-modeling, or the incorporation of prior knowledge. Successfully addressing this challenge will not only broaden the scope of spectral analysis but also unlock the full potential of these models in diverse fields, ranging from signal processing and medical imaging to financial modeling and materials science, ultimately enabling meaningful insights even when data is scarce.

The pursuit of interpretable models, as demonstrated by this work on spectral kernel discovery via PFNs, echoes a fundamental truth about all systems. Every failure to fully understand a network’s behavior is a signal from time – a reminder that complexity inevitably obscures mechanistic insight. This research doesn’t merely optimize performance; it attempts a dialogue with the past, extracting kernels that reveal the underlying processes. As Bertrand Russell observed, “The difficulty lies not so much in developing new ideas as in escaping from old ones.” This framework, by moving beyond purely predictive models, embodies that escape, seeking explicit representation where implicit function approximation once held sway, acknowledging the inevitable decay of opaque systems and striving for graceful aging through understanding.

What’s Next?

The extraction of interpretable kernels from Prior-Data Fitted Networks, as demonstrated, represents a slowing of entropy – a momentary reprieve from the black box. Each commit in this lineage is a record, and each version a chapter, yet the fundamental challenge remains: the system, however transparent at a given moment, will inevitably accrue complexity. Future iterations must address the inherent trade-off between kernel expressiveness and computational tractability. The current framework offers explicit construction, but scaling to high-dimensional or deeply nested networks presents a clear bottleneck; delaying fixes is a tax on ambition.

A compelling, though perhaps asymptotic, direction lies in the exploration of kernel priors – not merely as regularization terms, but as generative models for spectral density itself. This would necessitate a shift from reactive kernel discovery to proactive kernel design, allowing for the instantiation of kernels tailored to specific inductive biases. The question isn’t simply what kernel best represents the network, but what kernel should the network become.

Ultimately, this line of inquiry serves as a reminder that predictive power, while valuable, is a transient metric. True understanding resides not in the ability to forecast, but in the capacity to reconstruct the underlying generative process-to trace the decay, and perhaps, to guide it with a little grace.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.21731.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- TON PREDICTION. TON cryptocurrency

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- 10 Hulu Originals You’re Missing Out On

- The 11 Elden Ring: Nightreign DLC features that would surprise and delight the biggest FromSoftware fans

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 📅 BrownDust2 | August Birthday Calendar

- MP Materials Stock: A Gonzo Trader’s Take on the Monday Mayhem

- The Gambler’s Dilemma: A Trillion-Dollar Riddle of Fate and Fortune

- Walmart: The Galactic Grocery Giant and Its Dividend Delights

- Leaked Set Footage Offers First Look at “Legend of Zelda” Live-Action Film

2026-01-31 00:11