Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research tackles the complex challenge of intersectional bias in machine learning models, offering a robust framework for fairer and more equitable results.

This paper introduces a mixed-integer optimization approach to detect and mitigate bias across multiple sensitive attributes, improving fairness without sacrificing performance or interpretability.

Despite increasing demands for fairness in high-stakes artificial intelligence applications, current bias mitigation strategies often fail to address disparities experienced at the intersection of multiple protected groups. This paper, ‘Intersectional Fairness via Mixed-Integer Optimization’, introduces a novel framework leveraging mixed-integer optimization to train classifiers that demonstrably reduce intersectional bias while maintaining model performance. We prove the equivalence of key fairness metrics and empirically show improved bias detection, enabling the creation of interpretable models that bound unfairness below a specified threshold. Could this approach provide a robust and transparent solution for ensuring equitable outcomes in regulated industries and beyond?

Unveiling the Hidden Biases Within the Machine

As artificial intelligence systems become increasingly integrated into daily life – from loan applications and hiring processes to criminal justice and healthcare – the potential for algorithmic bias presents a substantial threat to fairness and equity. These systems, while appearing objective, are trained on data that often reflects existing societal biases, inadvertently perpetuating and even amplifying discriminatory outcomes. The reliance on these algorithms, therefore, isn’t simply a matter of technological advancement; it’s a socio-technical challenge demanding careful consideration of how data collection, model development, and deployment can unintentionally disadvantage certain groups. This isn’t about malicious intent, but rather the subtle ways in which systemic inequalities can become embedded within the very tools designed to optimize decision-making, necessitating robust methods for detection, mitigation, and ongoing monitoring.

Algorithmic bias isn’t simply a matter of coding errors; rather, it arises from deeply embedded systemic issues within the data and the very architecture of predictive models. Datasets often reflect historical inequalities and societal prejudices, inadvertently teaching algorithms to perpetuate – and even amplify – these biases. Furthermore, the choices made during model design – from feature selection to algorithm choice – introduce further opportunities for unfairness. Consequently, seemingly neutral algorithms can produce disparate outcomes, disproportionately impacting marginalized groups in areas like loan applications, criminal justice, and even healthcare. This isn’t a failure of technology itself, but a clear demonstration that algorithms are only as equitable as the data and design principles they embody, demanding careful scrutiny and proactive mitigation strategies.

Mitigating algorithmic bias demands more than simply applying conventional definitions of fairness, as these often prove inadequate when confronting the nuanced realities of societal harm. Current approaches frequently focus on statistical parity or equal opportunity, yet fail to account for historical disadvantages or the compounding effects of bias across multiple systems. A truly proactive response necessitates a shift toward intersectional fairness, acknowledging that individuals belong to multiple protected groups and experience discrimination in complex, interwoven ways. Furthermore, it requires moving beyond purely technical solutions to incorporate ethical considerations, stakeholder engagement, and ongoing monitoring for unintended consequences, ultimately recognizing that fairness is not a static metric, but a dynamic process of continuous improvement and accountability.

Beyond Single Attributes: Deconstructing Intersectional Bias

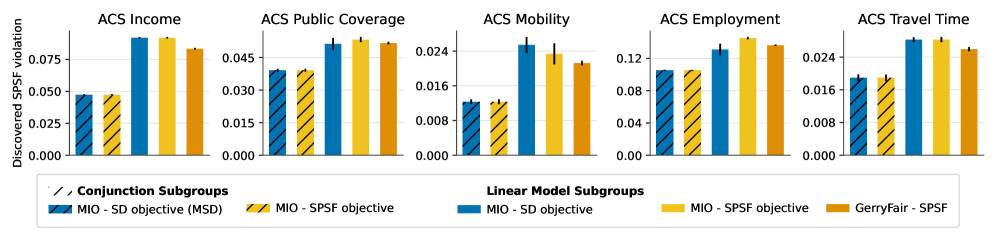

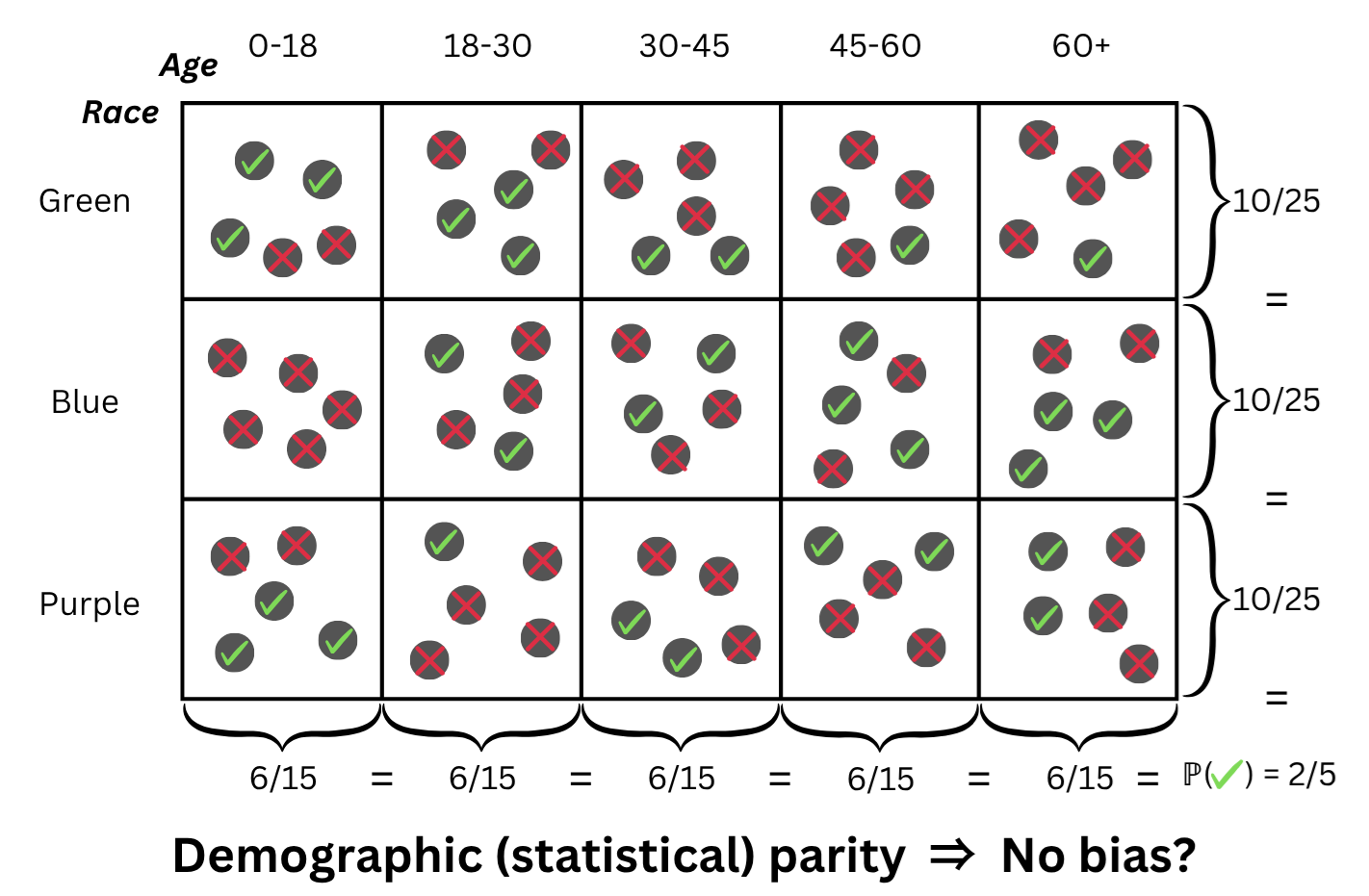

Intersectional fairness represents an evolution of traditional fairness metrics in algorithmic decision-making. Standard criteria such as Statistical Parity and Equal Opportunity typically assess fairness across single protected attributes – for example, race or gender – in isolation. Intersectional fairness extends these analyses to consider the overlap of multiple protected characteristics. This means evaluating outcomes not just for the general population, or for individuals defined by a single attribute, but specifically for subgroups defined by the intersection of those attributes – such as Black women, or elderly Hispanic men. This approach recognizes that individuals can experience disadvantage stemming from the combined effect of multiple forms of discrimination, and aims to identify and mitigate disparities that would be obscured by analyzing single attributes alone.

Analyzing fairness through the lens of intersectionality requires evaluating model performance not simply across single protected attributes, such as race or gender, but specifically within subgroups created by the combination of those attributes. This means calculating fairness metrics – like statistical parity difference or equal opportunity difference – for groups defined by the intersection of characteristics (e.g., Black women, Asian men), rather than solely for the broader categories of “women” or “Black individuals”. This granular approach identifies disparities that may be masked when considering single attributes in isolation; a model might exhibit overall statistical parity but still demonstrate significant disparate impact within a specific intersectional subgroup. Consequently, intersectional analysis provides a more nuanced and accurate assessment of fairness and helps pinpoint areas where mitigation strategies are most needed to address inequitable outcomes.

Identifying and mitigating disparate impact requires analysis beyond aggregate fairness metrics and necessitates examination of subgroups created by the intersection of protected attributes. These “conjunction subgroups” – formed by applying ‘and’ logic to attribute combinations (e.g., female and African American) – can reveal fairness discrepancies masked when considering single attributes in isolation. Disparate impact may not be apparent when analyzing overall outcomes, but become visible when evaluating performance within these specific, intersecting demographic segments. This granular approach allows for targeted interventions addressing fairness issues affecting particularly vulnerable groups and ensures a more equitable outcome for all individuals, not just the majority population.

Quantifying Disparity: The Metrics of Equitable Outcomes

Fairness assessment in intersectional settings utilizes both Ratio-based and Distance-based Fairness Measures. Ratio-based measures, such as Statistical Parity Difference and Equal Opportunity Difference, compare the rates of positive outcomes across subgroups by calculating the ratio of these rates. Distance-based measures, including Demographic Parity and Equalized Odds, quantify the divergence between outcome distributions using metrics like the Kullback-Leibler divergence or the Wasserstein distance. These calculations allow for the identification and quantification of disparities experienced by specific intersectional subgroups, providing a numerical basis for evaluating fairness and informing mitigation strategies. The selection of an appropriate measure depends on the specific fairness definition being prioritized and the characteristics of the data being analyzed.

Quantifying disparity between subgroups relies on comparing their outcome distributions using statistical measures. These methods calculate the difference in key metrics – such as acceptance rates, error rates, or resource allocation – across defined groups. For example, a ratio of outcomes between a privileged and disadvantaged group exceeding a predetermined threshold indicates a disparity. Distance-based measures, like the Kolmogorov-Smirnov statistic or the Jensen-Shannon divergence, provide a numerical assessment of the separation between these distributions, offering a more granular understanding of the degree of difference. These quantifiable metrics allow for objective evaluation of fairness and facilitate the tracking of progress during mitigation efforts, moving beyond subjective assessments.

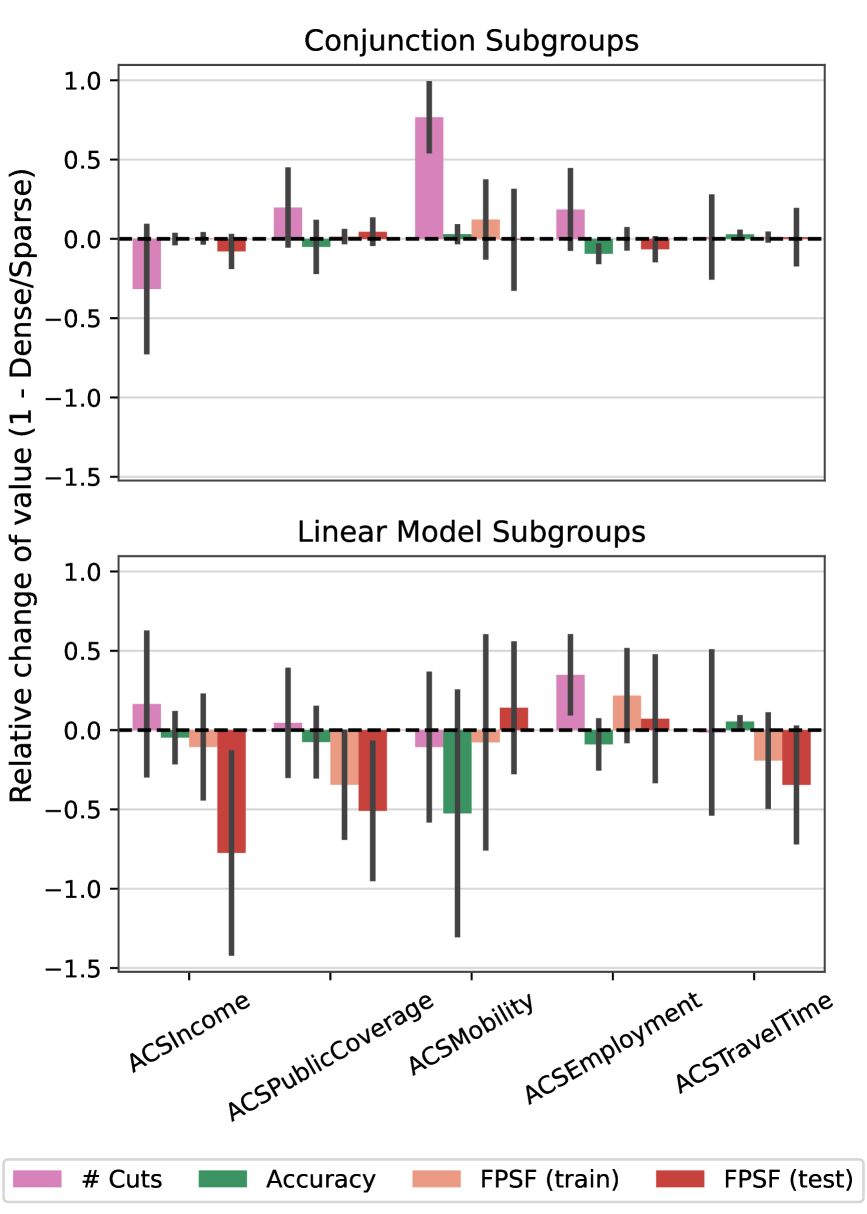

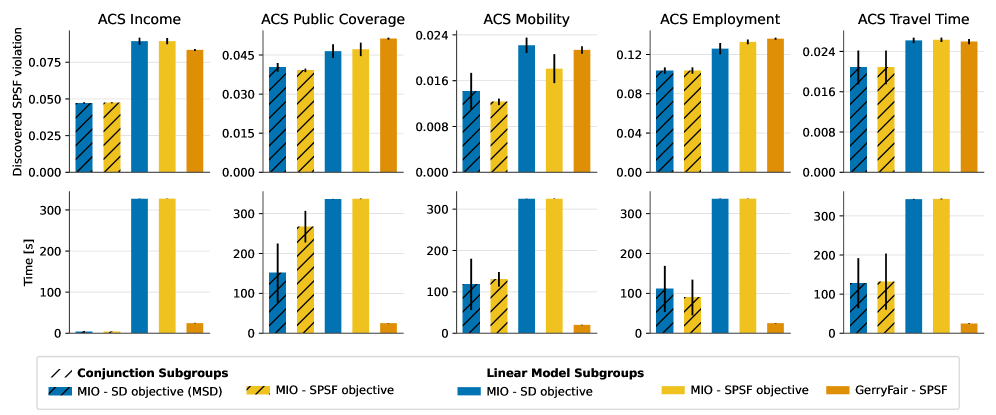

The implemented fairness framework demonstrably reduces disparity, achieving a Fairness Violation (FPSF) score consistently below 1.5 times the established threshold. This represents a significant performance improvement when compared to baseline models lacking dedicated fairness constraints. Analysis of subgroups, particularly those definable through Linear Subgroups – characterized by specific feature combinations impacting outcomes – allows for the identification of populations disproportionately affected by unfair predictions. This granular understanding facilitates the development of targeted mitigation strategies, enabling interventions tailored to address the root causes of disparity within those specific subgroups and improve overall system equity.

Constructing a Fairer Future: Frameworks for Bias Mitigation

The translation of abstract fairness principles into practical application requires robust bias mitigation frameworks. These frameworks serve as a crucial bridge, transforming ethical aspirations into actionable guidelines and enforceable regulations for artificial intelligence systems. Without such structured approaches, fairness remains a nebulous concept, susceptible to subjective interpretation and inconsistent implementation. By providing a standardized methodology for identifying, assessing, and rectifying bias throughout the AI lifecycle – from data collection and model training to deployment and monitoring – these frameworks empower developers and policymakers to proactively address potential harms and ensure equitable outcomes. Their importance extends beyond technical considerations, fostering public trust and enabling the responsible innovation of AI technologies that benefit all members of society.

Algorithmic bias, if left unchecked, can perpetuate and amplify societal inequalities; therefore, robust mitigation frameworks are essential for responsible AI development. These frameworks don’t simply address bias as an afterthought, but rather integrate fairness considerations throughout the entire AI lifecycle – from initial data collection and preprocessing to model training, evaluation, and deployment. A structured approach allows developers to systematically identify potential sources of bias, assess their impact on different demographic groups, and implement targeted interventions – such as data re-weighting or algorithmic adjustments – to minimize discriminatory outcomes. This proactive strategy moves beyond reactive bias detection, fostering a continuous cycle of monitoring and improvement that ensures AI systems are not only accurate and efficient, but also equitable and just in their application.

A novel bias mitigation framework leverages the power of Mixed-Integer Optimization to actively enforce fairness criteria within artificial intelligence systems. This approach demonstrably achieves a mean of 47 distinct fairness constraints – effectively ‘cutting’ biased outcomes – while impressively maintaining accuracy levels comparable to those of unbiased baseline models. Critically, the framework completes bias detection within a swift 5-minute timeframe, a performance benchmark that favorably positions it against existing tools like GerryFair. These results highlight the viability of proactive, mathematically-grounded interventions, and underscore the essential role such frameworks play in ensuring AI technologies deliver equitable benefits across all societal demographics.

The pursuit of ‘intersectional fairness’-a concept this paper tackles with mixed-integer optimization-feels less like solving a problem and more like a meticulously designed stress test. It’s a systematic probing of model vulnerabilities, exposing biases hidden within intersecting demographic groups. Vinton Cerf aptly noted, “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” This framework, however, isn’t about conjuring fairness from thin air; it’s about revealing the mechanics of bias-the code-level illusions-and rebuilding the system with transparency. The elegance lies in its approach: not simply demanding equitable outcomes, but defining fairness as a constraint within the optimization process, effectively forcing the model to account for these intersections. It’s a calculated dismantling, followed by a deliberate reconstruction, all in the name of uncovering what was previously hidden.

What Lies Ahead?

The pursuit of ‘fairness’ through formal optimization reveals a predictable truth: defining fairness is the real bottleneck, not the computation. This work, while elegantly applying mixed-integer programming to intersectional bias, merely formalizes existing assumptions about parity. The system will optimize for what it is told to optimize for-the interesting failures will occur at the edges of those definitions. One anticipates scenarios where minimizing bias in one intersection paradoxically exacerbates it in another, revealing the inherent trade-offs in any multi-objective function. The true test isn’t achieving a desired statistical outcome, but understanding why that outcome necessitates certain compromises.

Future iterations must move beyond simply detecting bias, and instead focus on building models that actively signal their limitations. A machine learning system that admits its inability to generalize across certain demographics is, paradoxically, more trustworthy than one that offers a confidently incorrect prediction. The field needs to embrace ‘controlled failure’ – intentionally introducing perturbations to reveal the sensitivity of the model to protected attributes. This approach is less about achieving a utopian ideal of unbiased prediction and more about creating a system capable of honestly communicating its boundaries of competence.

Ultimately, this line of inquiry highlights a fundamental point: algorithms are mirrors. They reflect not just the data they are trained on, but also the values – and the blind spots – of those who design them. The challenge, then, isn’t to eliminate bias entirely, but to make it visible, auditable, and subject to ongoing critical examination. A model’s ‘fairness’ is less a property of the code, and more a reflection of the questions we dare to ask.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.19595.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- TON PREDICTION. TON cryptocurrency

- Gold Rate Forecast

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- Nikki Glaser Explains Why She Cut ICE, Trump, and Brad Pitt Jokes From the Golden Globes

- Sandisk: A Most Peculiar Bloom

- Here Are the Best Movies to Stream this Weekend on Disney+, Including This Week’s Hottest Movie

- IonQ: A Quantum Flutter, 2026

- Ephemeral Engines: A Triptych of Tech

- Meta: A Seed for Enduring Returns

2026-01-29 02:51