Author: Denis Avetisyan

New research reveals that carefully crafted self-supervised learning techniques can unlock more sensitive brain imaging biomarkers for earlier and more accurate Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis.

A novel self-supervised learning framework leveraging structural MRI features outperforms traditional methods in identifying subtle indicators of Alzheimer’s disease.

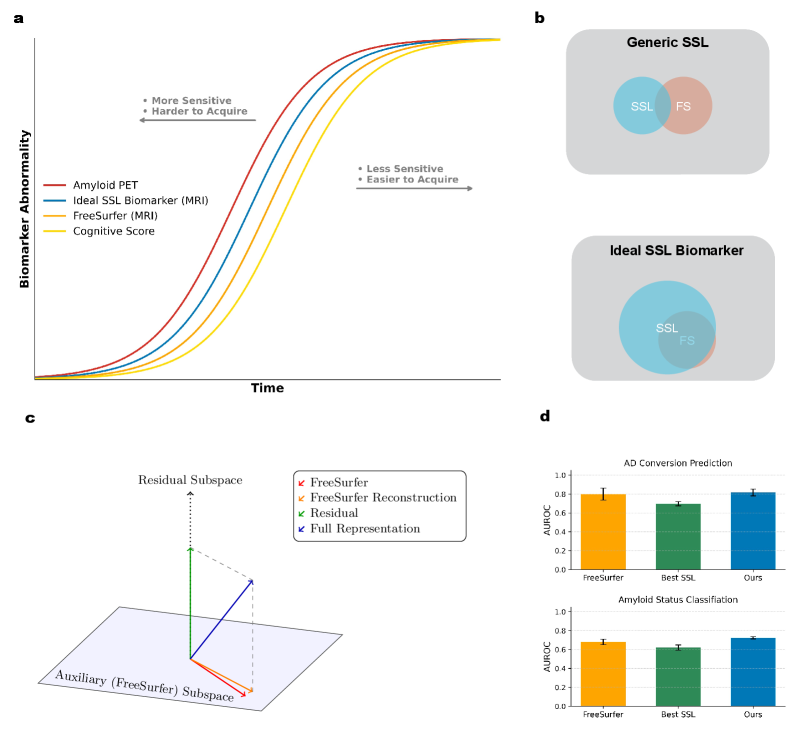

Despite the promise of automated feature discovery, applying self-supervised learning (SSL) to neuroimaging data has yielded surprisingly limited gains over established techniques. This is the central question explored in ‘A Cautionary Tale of Self-Supervised Learning for Imaging Biomarkers: Alzheimer’s Disease Case Study’, which investigates whether SSL can unlock more sensitive Alzheimer’s disease biomarkers from structural MRI. By introducing Residual Noise Contrastive Estimation (R-NCE), a novel framework integrating traditional features with augmentation-invariant learning, the authors demonstrate superior performance across multiple benchmarks, including prediction of disease conversion and associations with genetic factors linked to neurodegenerative processes. Could this approach, leveraging both established knowledge and learned representations, represent a critical step toward earlier and more accurate diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease?

The Inevitable Decay: Seeking Predictive Signals in a Noisy System

The pursuit of effective therapies for neurodegenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer’s, is severely hampered by the late-stage diagnosis typical with current methods. Often, noticeable cognitive decline indicates substantial, irreversible brain damage has already occurred, limiting the potential for preventative interventions. Consequently, a significant focus within neurological research centers on identifying sensitive biomarkers – measurable indicators detectable long before clinical symptoms manifest. These biomarkers ideally would reveal the earliest pathological changes associated with these diseases, allowing for proactive strategies aimed at slowing progression or even preventing onset. The challenge lies in discerning subtle, early signals from the natural variations in brain health, necessitating increasingly sophisticated analytical techniques and a deeper understanding of the molecular and structural changes that precede cognitive impairment.

The current approach to diagnosing neurodegenerative diseases frequently centers on observable clinical symptoms, a strategy inherently limited by the insidious nature of these conditions. By the time cognitive decline or motor impairments become clinically apparent, significant and often irreversible neurological damage has already occurred. This reliance on late-stage indicators drastically reduces the window for effective preventative interventions, as therapeutic strategies are often most successful when applied before substantial neuronal loss. Consequently, treatments aimed at slowing disease progression or improving quality of life face considerable challenges, highlighting the urgent need for biomarkers capable of detecting pathological changes at much earlier, pre-symptomatic stages, and allowing for proactive healthcare strategies.

The concept of a ‘Brain Age Gap’ represents a novel approach to evaluating neurological well-being, moving beyond simple disease diagnosis to quantify an individual’s brain health trajectory. Rather than focusing solely on the presence of pathology, this metric establishes a predicted brain age based on complex analyses of neuroimaging data – typically from MRI scans – and compares it to a person’s chronological age. A widening gap – where the predicted brain age exceeds actual age – may signal accelerated cognitive decline and increased vulnerability to neurodegenerative diseases, even before the appearance of noticeable symptoms. This quantifiable difference offers the potential for early risk assessment and the tracking of interventions designed to promote brain resilience, ultimately shifting the focus from reactive treatment to proactive prevention and personalized brain health management.

Accurate estimation of the ‘Brain Age Gap’ relies heavily on the detailed insights provided by neuroimaging techniques, particularly magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). MRI allows researchers to move beyond subjective assessments and quantify structural and functional brain changes with unprecedented precision. By analyzing MRI scans, algorithms can predict a ‘brain age’ based on observed characteristics – things like gray matter volume, white matter integrity, and network connectivity. A significant discrepancy between this predicted age and a person’s chronological age – the ‘Brain Age Gap’ – signals potential neurodegeneration, even before the emergence of noticeable cognitive symptoms. This proactive approach allows for the identification of individuals at heightened risk, opening opportunities for early interventions and potentially delaying, or even preventing, the onset of debilitating neurodegenerative diseases. The power of MRI, therefore, isn’t simply in seeing the brain, but in predicting its future health.

Escaping the Subjectivity: Automating Feature Extraction from Noise

Traditional analysis of Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) data relies heavily on manual feature extraction, a process where trained radiologists or experts identify and quantify specific anatomical or pathological characteristics. This method is inherently time-consuming, requiring substantial clinician effort for each scan analyzed. Furthermore, manual extraction is susceptible to inter-rater variability; different experts may delineate the same features differently, introducing subjective bias into the analysis and potentially impacting diagnostic accuracy and the reproducibility of research findings. The time and resource demands, coupled with the potential for bias, limit the scalability of manual feature extraction for large-scale studies and clinical applications.

Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) addresses limitations of traditional machine learning by eliminating the need for extensive manual annotation of imaging datasets. Instead of relying on labeled data, SSL algorithms leverage the inherent structure within unlabeled MRI scans to learn useful feature representations. This is achieved by formulating pretext tasks – artificial predictive problems designed to force the model to understand underlying data characteristics – such as predicting missing image patches or the spatial arrangement of image components. The model learns to extract features that are effective for solving these pretext tasks, and these learned representations can then be transferred to downstream tasks like disease classification or segmentation with minimal fine-tuning, significantly reducing the reliance on costly and time-consuming expert labeling.

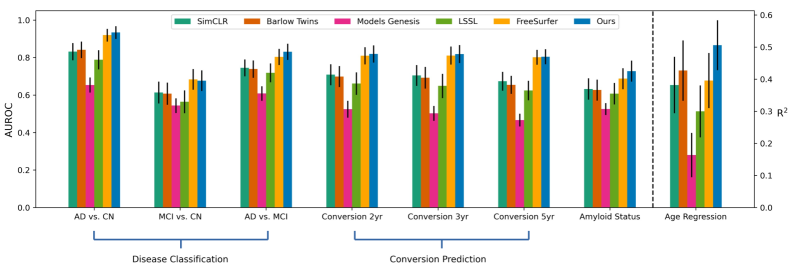

Self-supervised learning (SSL) methods such as Models Genesis, SimCLR, and Barlow Twins extract robust image features without requiring manual labels. Models Genesis learns by generating synthetic image patches and training a network to discriminate between real and generated content. SimCLR maximizes the agreement between different augmented views of the same image, creating representations invariant to transformations. Barlow Twins minimizes the cross-correlation between the outputs of different layers in a neural network, encouraging the learning of independent and informative features. These techniques operate by defining pretext tasks – reconstruction or correlation minimization – that force the model to learn meaningful representations of the input data as a byproduct of solving the task.

Longitudinal Self-Supervised Learning (SSL) enhances feature representation by leveraging temporal data. This approach processes imaging data collected from the same subjects at multiple time points, establishing a correspondence between features extracted from different visits. By minimizing the discrepancy between these aligned features, the model learns representations that are robust to natural variations in image appearance and sensitive to disease-related changes over time. This alignment process, performed across a cohort of subjects, effectively creates a consistent feature space, improving the accuracy and generalizability of downstream tasks such as disease classification and progression monitoring, without requiring manual labeling of the temporal data.

From Signals to Substance: Quantifying the Inevitable Decline

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) data can be quantitatively analyzed using neuroimaging software such as FreeSurfer to derive measurements of brain structure. Specifically, FreeSurfer algorithms enable the calculation of Cortical Thickness, representing the thickness of the cerebral cortex, and Subcortical Volume, quantifying the size of deep gray matter structures including the hippocampus, amygdala, and thalamus. These measurements are obtained through automated image processing pipelines that segment the brain, identify cortical surfaces, and calculate volumetric parameters. The resulting metrics provide quantifiable data on brain morphology that can be used to assess individual differences and track changes over time, forming the basis for numerous neuroscientific investigations and clinical applications.

The integration of structural MRI-derived measurements, such as cortical thickness and subcortical volume, with representations generated through self-supervised learning (SSL) techniques demonstrates increased predictive capability. Specifically, employing Residual Noise Contrastive Estimation (R-NCE) as the SSL method yields superior performance compared to utilizing raw FreeSurfer outputs and other established SSL approaches like SimCLR. R-NCE achieves this enhancement by learning robust feature representations from the data itself, effectively capturing subtle structural variations that contribute to improved predictive accuracy in tasks like age prediction, Alzheimer’s Disease conversion prediction, and amyloid sensitivity assessment. This improved performance indicates that R-NCE effectively complements traditional structural MRI analysis by providing a more nuanced and informative feature space.

Analysis of cortical thickness and subcortical volume, derived from MRI scans of large-scale cohorts such as the UK Biobank and the Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative (ADNI), enables the detection of subtle structural alterations associated with preclinical disease stages. These cohorts, comprising tens of thousands of individuals, provide the statistical power necessary to identify minute differences in brain structure that may not be apparent in smaller studies. Longitudinal data within these cohorts facilitates tracking of structural changes over time, allowing for the identification of trajectories indicative of disease progression before the onset of clinical symptoms. Specifically, these metrics can reveal early atrophy in regions vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease or other neurodegenerative conditions, offering potential biomarkers for early detection and intervention.

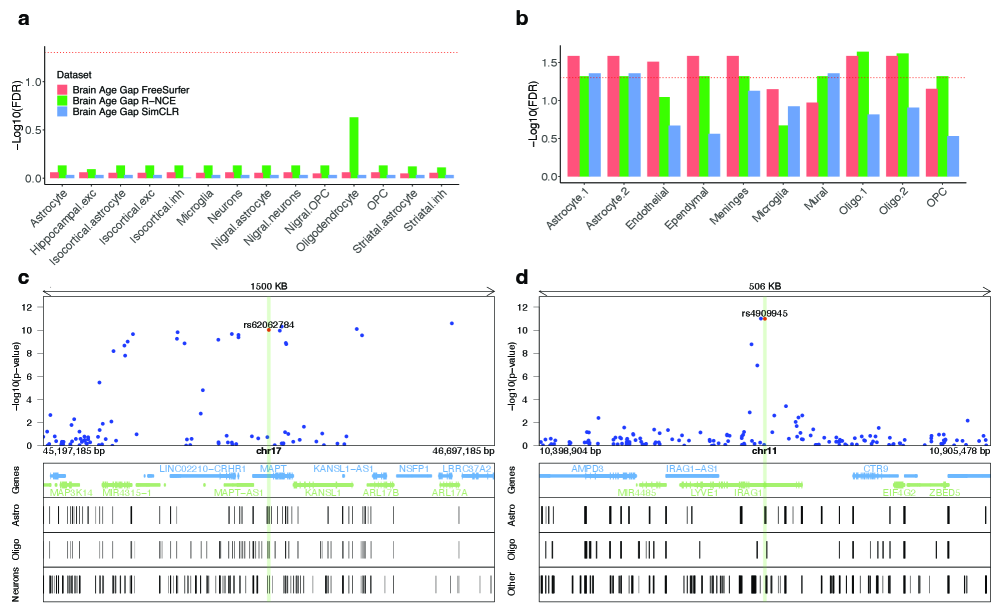

Genome-Wide Association Studies (GWAS) and Linkage Disequilibrium Score Regression (LDSC) are utilized to dissect the genetic architecture underlying structural brain variations quantified from MRI data. GWAS identifies specific genetic variants – single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) – associated with differences in cortical thickness and subcortical volume. LDSC then refines these findings by estimating the heritability explained by these genetic variants and partitioning it into different genomic annotations, including the identification of expression Quantitative Trait Loci (eQTLs). eQTLs represent genomic regions where genetic variation influences gene expression levels, thereby linking structural brain traits to underlying molecular mechanisms and potential causal genes.

Evaluation of age prediction accuracy demonstrates that Residual Noise Contrastive Estimation (R-NCE) achieves a Mean Absolute Error (MAE) of 4.05 years. This represents a statistically significant improvement over both FreeSurfer, which yielded an MAE of 4.56 years, and the SimCLR self-supervised learning method, which produced an MAE of 4.65 years. These results indicate that R-NCE effectively captures structural information from MRI scans that is more strongly correlated with chronological age than features derived using traditional FreeSurfer pipelines or alternative self-supervised learning techniques.

Analysis demonstrates that Residual Noise Contrastive Estimation (R-NCE) significantly improves prediction of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) conversion over a 2-year period, with a p-value of less than 0.0001 when compared to features derived solely from FreeSurfer. Furthermore, R-NCE exhibits superior performance in identifying amyloid sensitivity, also with a p-value of less than 0.0001 compared to FreeSurfer-derived features. These results indicate that the SSL-derived representations generated by R-NCE capture information relevant to early AD pathology and disease progression not fully represented by traditional volumetric and cortical thickness measurements.

Beyond Reaction: Towards Proactive Management of Inevitable Decline

A novel predictive framework combines insights from self-supervised learning (SSL) with conventional structural magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to estimate an individual’s ‘Brain Age Gap’ – the difference between their predicted brain age and their chronological age. This integration leverages the power of SSL to extract subtle, yet meaningful, features from MRI scans that might otherwise be missed, enhancing the accuracy of predicting those at heightened risk of Alzheimer’s Disease. By quantifying this gap, researchers can identify individuals exhibiting accelerated brain aging, potentially years before the onset of clinical symptoms, and offering a crucial window for early intervention and preventative strategies. The approach demonstrates a significant advancement beyond traditional risk assessment, moving toward a proactive model of neurodegenerative disease management.

The potential for proactive intervention in neurodegenerative diseases represents a paradigm shift in treatment strategies, moving beyond reactive care to preventative measures. By identifying individuals at risk – through predictive modeling of the ‘Brain Age Gap’ and analysis of structural MRI data – clinicians can begin personalized treatment plans years before the emergence of clinical symptoms. This early intervention may involve lifestyle modifications, targeted therapies, or enrollment in clinical trials designed to slow disease progression. Importantly, delaying the onset of neurodegeneration, even by a few years, can significantly improve an individual’s quality of life and reduce the societal burden associated with these devastating conditions; mitigating the severity of symptoms through preemptive action offers a crucial opportunity to preserve cognitive function and independence for longer.

The potential to proactively address neurodegeneration hinges on the capacity to identify at-risk individuals before significant brain damage occurs, and large-scale population studies employing routinely collected Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) data offer a practical pathway to achieve this. By analyzing the brain scans of vast cohorts, researchers can pinpoint subtle structural variations – indicators of early neurodegenerative processes – that might otherwise go unnoticed. This isn’t about scanning entire populations, but rather leveraging the wealth of MRI data already acquired for clinical purposes. Statistical models can then highlight individuals exhibiting patterns suggestive of an accelerated ‘Brain Age Gap’, effectively flagging those most likely to benefit from preventative lifestyle modifications or, in the future, targeted therapies. Such a strategy shifts the focus from reactive treatment of established disease to proactive intervention, potentially delaying onset or lessening the severity of conditions like Alzheimer’s and offering a new paradigm for neurological healthcare.

Ongoing investigation centers on enhancing the precision of neurodegenerative disease prediction through iterative model refinement and the integration of multi-modal data-combining genetics, structural MRI, and potentially other biomarkers like cerebrospinal fluid analysis. This isn’t merely about earlier diagnosis; researchers are actively pursuing the identified genetic and structural variations as potential therapeutic targets. Specifically, pathways influencing brain plasticity and resilience are being explored for interventions designed to slow, halt, or even reverse the neurodegenerative process. The ultimate goal is to move beyond reactive treatment towards proactive, personalized strategies that address individual risk factors and bolster the brain’s inherent capacity to withstand disease, potentially delaying symptom onset and improving long-term cognitive health.

Research indicates a substantial genetic influence on an individual’s ‘Brain Age Gap’ – the difference between predicted and actual brain age – as demonstrated by a heritability estimate of 0.42 for R-NCE BAG. This finding suggests that a significant portion of the variation observed in brain structural differences, and thus the rate of brain aging, is attributable to inherited factors. Consequently, identifying specific genetic variants associated with a larger Brain Age Gap could prove crucial for pinpointing individuals predisposed to neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s. Understanding this genetic component opens avenues for developing risk prediction tools and, ultimately, personalized preventative strategies tailored to an individual’s genetic profile, potentially delaying or lessening the impact of age-related cognitive decline.

The pursuit of increasingly sensitive biomarkers, as demonstrated in this study of Alzheimer’s disease, inevitably invites a degree of fragility. The framework’s success hinges on incorporating auxiliary structural MRI features-a refinement that, while enhancing sensitivity, also introduces potential points of failure. This mirrors a fundamental truth about complex systems; the more exquisitely tuned they become, the less resilient they are to unforeseen perturbations. As Donald Davies observed, “A system that never breaks is dead.” The very act of seeking improvement, of pushing the boundaries of representation learning, necessitates a willingness to accept-even embrace-the inevitability of systemic breakdown as a pathway to further refinement. Perfection, in this context, leaves no room for people – or, more accurately, no room for the ongoing process of learning and adaptation inherent in truly robust systems.

The Turning of the Wheel

The pursuit of biomarkers, even with the elegance of self-supervision, remains a sculpting of shadows. This work, while demonstrating gains in sensitivity, only refines the question, not the answer. Every dependency on structural MRI-every feature coaxed from the data-is a promise made to the past, a belief in the stability of what is to predict what will be. The brain ages, and so do the assumptions baked into these representations. The ‘brain age gap’ itself is merely a moving target, a symptom shifting under the weight of observation.

The true challenge isn’t simply to detect earlier, but to anticipate the system’s inevitable drift. Control is an illusion that demands SLAs-service level agreements with the very entropy the science attempts to hold at bay. Future work will likely focus on dynamic representations, models that learn to unlearn, and architectures that embrace, rather than resist, the cyclical nature of neurological change.

Everything built will one day start fixing itself. The next iteration won’t be about creating better biomarkers, but about designing systems that can autonomously recalibrate, that acknowledge their own impermanence, and that understand the map is never the territory. The wheel turns, and the landscape reshapes itself regardless.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16467.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Building 3D Worlds from Words: Is Reinforcement Learning the Key?

- The Best Directors of 2025

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- 20 Best TV Shows Featuring All-White Casts You Should See

- Mel Gibson, 69, and Rosalind Ross, 35, Call It Quits After Nearly a Decade: “It’s Sad To End This Chapter in our Lives”

- Umamusume: Gold Ship build guide

- Uncovering Hidden Signals in Finance with AI

- TV Shows That Race-Bent Villains and Confused Everyone

- Gold Rate Forecast

- TV Shows Where Asian Representation Felt Like Stereotype Checklists

2026-01-27 05:23