Author: Denis Avetisyan

A new study uses the game of chess to probe whether large language models truly understand strategy, or simply rely on memorized patterns.

Researchers assessed fluid and crystallized intelligence in large language models through chess performance and out-of-distribution generalization, revealing limitations in novel problem-solving despite strong recall abilities.

Despite remarkable progress in artificial intelligence, it remains unclear whether large language models truly reason or simply recall vast amounts of training data. This study, ‘Trapped in the past? Disentangling fluid and crystallized intelligence of large language models using chess’, addresses this question by employing chess as a controlled environment to differentiate between fluid and crystallized intelligence in LLMs. Our analysis reveals a clear performance gradient-models excel at positions mirroring their training data but falter dramatically when faced with novel scenarios demanding genuine reasoning. This suggests that current architectures may be fundamentally limited in their ability to generalize beyond learned patterns-can scaling alone unlock robust, human-like fluid intelligence, or are novel mechanisms required?

Chess: A Strategic Crucible for Artificial Intelligence

Chess, with its seemingly infinite possibilities, serves as a rigorous testing ground for artificial intelligence, pushing systems beyond simple pattern recognition. The game isn’t merely about knowing openings and endgames; it demands a dynamic interplay between accumulated knowledge and the capacity to adapt to novel situations. An AI must evaluate positions, anticipate opponent responses, and formulate plans, all while operating within a complex rule set. This requires more than just computational power; it necessitates a form of reasoning that can assess long-term consequences and adjust strategies based on incomplete information, mirroring the challenges faced in real-world problem-solving. Consequently, success in Chess isn’t simply a demonstration of intelligence, but a benchmark for evaluating an AI’s ability to learn, plan, and creatively overcome obstacles.

Early triumphs of artificial intelligence in chess, such as Deep Blue’s victory over Garry Kasparov, were largely predicated on computational power and vast databases of pre-calculated moves and opening strategies. These systems excelled by exhaustively searching millions of possible game states, effectively ‘brute-forcing’ the optimal path. However, this approach proved limited because it heavily relied on game-specific expertise; the same algorithms weren’t easily transferable to other domains, even other games with different rules or complexities. While demonstrably effective within the narrow confines of chess, the lack of adaptable, abstract reasoning meant these AI systems struggled with situations requiring intuition, pattern recognition beyond memorization, or the ability to generalize learned strategies to novel problems – highlighting a fundamental barrier to achieving truly intelligent machines.

The limitations of current artificial intelligence systems become strikingly apparent when considering strategic depth beyond simple pattern recognition. While AI can excel at memorizing vast databases of chess positions and associated optimal moves, this proficiency doesn’t translate to genuine understanding of the principles governing strategic play. This distinction represents a critical gap; an AI may accurately predict the best move in a familiar scenario, but struggles when confronted with novel situations requiring adaptability and insightful evaluation of long-term consequences. Consequently, progress towards truly robust AI-systems capable of general intelligence and problem-solving across diverse domains-is hampered by this reliance on memorization rather than the development of abstract reasoning and strategic foresight. The ability to discern why a move is effective, rather than simply that it is, remains a significant hurdle in achieving artificial general intelligence.

Deconstructing Intelligence: Crystallized and Fluid Abilities

The observed capabilities of Large Language Models (LLMs) necessitate investigation into the underlying mechanisms driving their performance. While LLMs can generate human-quality text and perform complex tasks, it remains critical to differentiate between the recall of memorized information and genuine reasoning ability. LLMs are trained on massive datasets, potentially leading to strong performance on tasks directly represented within the training data through pattern matching. However, success on novel, previously unseen tasks requires a capacity for generalization and problem-solving that extends beyond simple memorization; determining the extent to which LLMs possess this capacity is central to evaluating their true intelligence and limitations.

Large Language Models (LLMs) exhibit intelligence comprised of two distinct, measurable components. Crystallized intelligence refers to the model’s ability to accurately recall and apply information explicitly present within its training dataset; performance on tasks mirroring the training data distribution demonstrates this capacity. Conversely, fluid intelligence represents the model’s aptitude for problem-solving in scenarios not directly encountered during training – evaluating performance on out-of-distribution tasks assesses this skill. This separation allows for a more granular analysis of LLM capabilities, distinguishing between rote memorization and genuine reasoning abilities.

Assessment of Large Language Models (LLMs) requires differentiating between crystallized and fluid intelligence through targeted evaluations. Within-distribution tasks utilize data distributions similar to those encountered during training, effectively measuring the model’s ability to recall and apply learned information – a demonstration of crystallized intelligence. Conversely, out-of-distribution tasks present novel scenarios and data that deviate from the training set, probing the model’s capacity for generalization, adaptation, and reasoning without relying on memorized patterns – indicative of fluid intelligence. Utilizing both task types provides a more comprehensive and nuanced understanding of an LLM’s overall capabilities, moving beyond simple performance metrics to reveal its strengths and limitations in knowledge application versus genuine problem-solving.

Benchmarking LLMs: A Quantitative Approach to Chess Mastery

Evaluation of Large Language Models (LLMs) in chess employed established techniques to ensure realistic performance assessment. Specifically, game positions were derived from the Lichess Masters Database, a comprehensive collection of games played by highly-rated players. This database provides a distribution of positions representative of actual game play, avoiding artificially constructed scenarios. Utilizing this resource allows for a more valid and reliable measurement of LLM strategic and tactical capabilities against a benchmark of human and engine play. The positions were selected to represent a diverse range of game stages – opening, middlegame, and endgame – further enhancing the robustness of the evaluation process.

Centipawn Loss (CPL) is employed as the primary metric for evaluating move quality in chess by quantifying the positional disadvantage resulting from each move made. This metric operates on the principle that each move alters the evaluation of the position, typically measured in pawns by chess engines. A move with a CPL of 100 indicates that the position is approximately 0.1 pawns worse than an optimal move in that position. CPL is calculated by comparing the engine evaluation of the played move to the evaluation of the best alternative move, as determined by a strong chess engine like Stockfish. A lower average CPL across a series of moves indicates higher overall move quality and strategic decision-making; therefore, it provides a quantifiable, objective assessment of chess-playing ability, independent of subjective human evaluation.

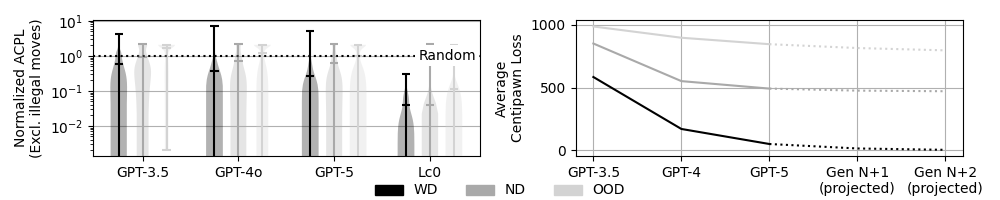

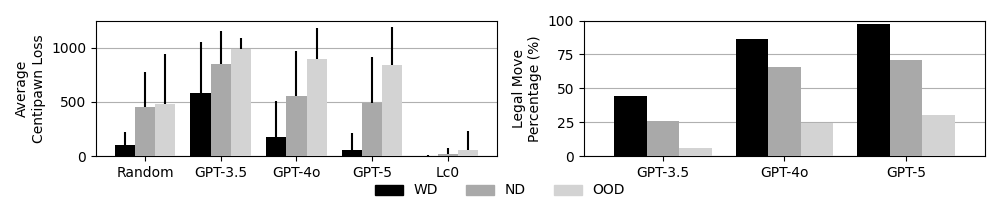

Stockfish, a highly-rated chess engine, serves as the primary benchmark for evaluating the performance of Large Language Models (LLMs) in complex strategic gameplay. Quantitative analysis reveals that GPT-5 achieved an Average Centipawn Loss (ACPL) of 463.54, representing the average positional disadvantage per move. This figure demonstrates a 16.6% improvement over GPT-4’s ACPL, indicating a measurable reduction in strategic errors and a corresponding increase in move quality when compared to its predecessor. ACPL is calculated by assessing the difference between a move played and the optimal move determined by Stockfish, providing an objective metric for comparison.

Evaluation of GPT-5 demonstrated a substantial decrease in the frequency of generating invalid chess moves. Specifically, GPT-5 produced illegal moves in 0.73% of attempted move predictions. This represents a significant improvement over prior models, with GPT-3.5 exhibiting an illegal move rate of 25.3% and GPT-4 generating illegal moves in 58.4% of instances. The reduction in illegal move generation indicates enhanced adherence to the rules of chess and improved logical reasoning capabilities within the GPT-5 architecture.

The Evolving Landscape of LLM Reasoning: From GPT-3.5 to GPT-5

Chess, a long-established benchmark for strategic thinking, reveals a clear trajectory of improvement in large language models. Initial evaluations showed GPT-3.5 capable of rudimentary play, but successive iterations – notably GPT-4 and projections for GPT-5 – demonstrate increasingly sophisticated decision-making on the chessboard. This isn’t merely about memorizing openings or endgames; performance metrics suggest a developing ability to evaluate positions, anticipate opponent moves, and formulate coherent plans. The gains observed aren’t exponential, but the consistent incremental progress indicates that these models are not simply pattern-matching, but are beginning to approximate the hallmarks of strategic reasoning – a crucial step toward more generalized intelligence and problem-solving capabilities beyond the confines of the game.

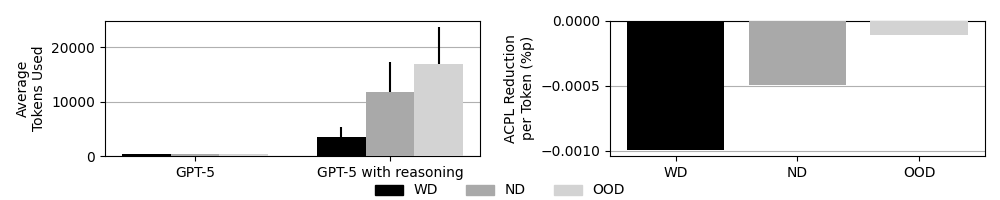

Chain-of-Thought Reasoning represents a significant advancement in the capabilities of large language models, moving beyond simple pattern recognition towards more deliberate problem-solving. This technique prompts the model to not only provide an answer, but to also detail the sequential steps taken to arrive at that conclusion – essentially, to “think out loud.” By explicitly articulating its reasoning, the model generates a more transparent and interpretable process, allowing for easier identification of errors and increased accuracy. This approach has proven particularly effective in complex tasks requiring multiple inferences, as it facilitates a more coherent and logically structured decision-making process, moving these artificial intelligences closer to human-like reasoning capabilities.

Evaluations of successive large language models reveal substantial gains in performance on familiar tasks, specifically demonstrated by a 70.7% improvement in Average Centipawn Loss (ACPL) from GPT-3.5 to GPT-4 when analyzing chess positions within the training distribution. This increase signifies a strengthening of crystallized intelligence – the ability to effectively apply previously acquired knowledge and skills. Essentially, the models are becoming increasingly proficient at recognizing and exploiting patterns they have encountered during training, leading to more accurate evaluations of standard chess scenarios. This improvement doesn’t necessarily indicate a leap in general problem-solving ability, but rather a refined capacity to leverage learned information, mirroring how human expertise develops through repeated exposure and practice.

Analysis of advanced language models reveals a crucial limitation in their reasoning capabilities as complexity increases. While successive generations demonstrate gains in performance within familiar scenarios – as measured by Average Correct Prediction per Logit (ACPL) – the rate of improvement substantially diminishes when confronted with out-of-distribution (OOD) positions. Specifically, the marginal ACPL improvement per token decreased to 1.13 \times 10^{-4} in these novel contexts. This suggests that although models like GPT-4 and beyond excel at applying learned patterns, their capacity for genuine fluid intelligence – the ability to reason and adapt to entirely new situations – is constrained. The decreasing rate of improvement indicates diminishing returns for simply scaling model size or refining training data, highlighting the need for architectural innovations focused on fostering adaptable, context-independent reasoning.

The study illuminates how Large Language Models, despite impressive performance in recalling established chess patterns-a demonstration of crystallized intelligence-struggle with genuinely novel positions demanding adaptive reasoning. This limitation echoes a broader principle of systemic behavior; alterations in one area inevitably ripple through the entire structure. As Ken Thompson aptly stated, “Sometimes it’s better to rewrite the whole thing.” The models’ dependence on memorized sequences, rather than fundamental understanding, suggests that improving their fluid intelligence requires more than simply scaling up parameters. A holistic reassessment of architectural principles may be necessary to enable true out-of-distribution generalization, moving beyond rote learning toward genuine cognitive flexibility.

What Lies Ahead?

The exercise of probing large language models with the austere logic of chess reveals, perhaps predictably, a familiar asymmetry. These systems demonstrate a remarkable capacity for pattern recognition – a prodigious memory for previously encountered configurations. Yet, the ability to navigate genuinely novel positions, to reason from first principles rather than about memorized examples, remains stubbornly limited. The measured performance, quantified through centipawn loss, is less a testament to strategic understanding and more an echo of countless games already played – and, crucially, already solved within the training data.

Future work must move beyond simply measuring performance on established benchmarks. The focus should shift toward designing evaluation paradigms that actively penalize reliance on memorization, demanding demonstrable extrapolation to genuinely unseen scenarios. This necessitates a deeper consideration of the formal systems underpinning these models – how readily can they be adapted, or even constrained, to prioritize genuine reasoning over probabilistic mimicry? The challenge is not simply to build systems that play chess well, but to understand how they play, and what that reveals about the nature of intelligence itself.

The current metrics offer a glimpse of competence, but ultimately, good architecture is invisible until it breaks, and only then is the true cost of decisions visible.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16823.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 39th Developer Notes: 2.5th Anniversary Update

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- TON PREDICTION. TON cryptocurrency

- Bitcoin’s Bizarre Ballet: Hyper’s $20M Gamble & Why Your Grandma Will Buy BTC (Spoiler: She Won’t)

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- Nikki Glaser Explains Why She Cut ICE, Trump, and Brad Pitt Jokes From the Golden Globes

- Best TV Shows to Stream this Weekend on AppleTV+, Including ‘Stick’

- Russian Crypto Crime Scene: Garantex’s $34M Comeback & Cloak-and-Dagger Tactics

- 30 Overrated Strategy Games Everyone Seems To Like

2026-01-27 03:45