Author: Denis Avetisyan

A novel collaboration between human intuition and artificial intelligence is proving surprisingly effective at identifying the most difficult cases for optimization algorithms.

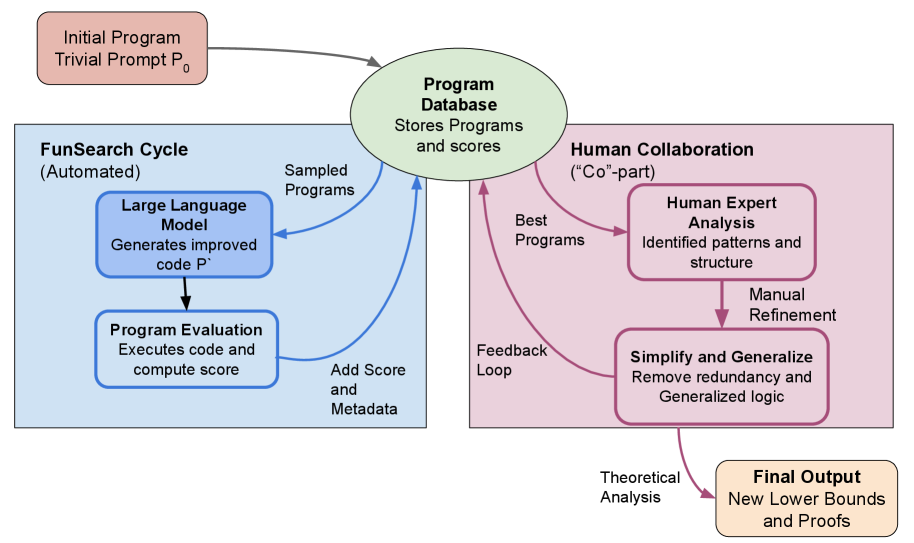

This work introduces Co-FunSearch, a method combining large language models with human search to generate adversarial instances for heuristics across combinatorial optimization problems.

Despite decades of progress in combinatorial optimization, establishing tight lower bounds for heuristic performance remains a significant challenge. This is addressed in ‘The Art of Being Difficult: Combining Human and AI Strengths to Find Adversarial Instances for Heuristics’, which introduces a collaborative approach-Co-FunSearch-leveraging both large language models and human expertise to generate challenging adversarial instances. This synergy yields state-of-the-art lower bounds for established heuristics on problems including hierarchical k-median clustering and the knapsack problem, even surpassing results achieved in over a decade for some cases. Could this human-AI collaboration unlock further breakthroughs in addressing notoriously difficult problems across theoretical computer science and beyond?

The Inevitable Limits of Simplification

A vast number of practical challenges, ranging from logistical planning to resource allocation, are fundamentally instances of combinatorial optimization. These problems involve selecting the best option from a discrete set of possibilities, a task that quickly becomes computationally intractable as the number of choices grows. A classic example is the Gasoline Problem, which seeks the most efficient route to visit a series of locations, demanding a careful evaluation of countless permutations. Unlike problems with continuous solutions, simply refining an initial guess isn’t sufficient; each potential arrangement must be considered, or a carefully designed strategy employed, to ensure a viable and, ideally, optimal solution is discovered within a reasonable timeframe. The sheer scale of these problems necessitates the development of efficient algorithms capable of navigating complex solution spaces and delivering practical results.

While commonly employed for their speed, traditional heuristics in combinatorial optimization frequently falter when confronted with intricate problem instances. These approaches, such as greedy algorithms or simple local search, prioritize computational efficiency over solution accuracy, often settling for ‘good enough’ rather than demonstrably optimal results. This trade-off stems from their inability to comprehensively explore the vast solution space inherent in these problems; as complexity increases – with more variables and constraints – the likelihood of these heuristics becoming trapped in suboptimal local minima grows significantly. Consequently, while they may provide a quick answer, there’s no assurance that the solution is even remotely close to the best possible arrangement, potentially leading to substantial inefficiencies or flawed decision-making in real-world applications like logistics, scheduling, and resource allocation.

The inherent shortcomings of heuristic approaches in tackling complex combinatorial challenges necessitate a shift towards methodologies that prioritize exhaustive or near-exhaustive solution space exploration. While heuristics offer speed, their reliance on simplifying assumptions can lead to suboptimal results, particularly as problem complexity increases. Consequently, research is increasingly focused on techniques – such as branch and bound, integer programming, and advanced local search algorithms – designed to systematically evaluate a wider range of potential arrangements. These methods, though potentially more computationally intensive, offer the crucial benefit of demonstrably approaching optimality, providing solutions with guaranteed bounds on their quality – a critical advantage in applications where even small improvements can yield significant gains or mitigate substantial risks. The pursuit of such systematic approaches represents a fundamental step toward resolving increasingly intricate real-world optimization problems.

Seeding Failure: LLMs as Adversarial Instance Generators

FunSearch employs Large Language Models (LLMs) to generate adversarial instances for algorithm testing, representing a departure from conventional methods. These instances are specifically crafted inputs designed to challenge and potentially expose weaknesses within heuristic algorithms. The process involves prompting the LLM to create inputs that maximize the likelihood of failure or suboptimal performance of the target heuristic. Unlike random or manually designed test cases, LLM-generated instances are iteratively refined based on the heuristic’s response, allowing for a focused and automated search for edge cases and vulnerabilities. This approach facilitates a more systematic evaluation of algorithm robustness and performance boundaries.

FunSearch’s iterative refinement process involves generating candidate adversarial instances with a Large Language Model, evaluating their performance against the target heuristic, and then using the results to guide the LLM in creating improved instances. This cycle repeats, with each iteration focusing on areas where the heuristic exhibits weakness. The system doesn’t simply identify failing cases; it actively shapes the input to maximize the probability of exposing performance boundaries and vulnerabilities within the heuristic’s logic. This targeted approach contrasts with random or manually created test cases, which lack the directed search for edge-case behavior that iterative refinement provides, and allows for a more efficient discovery of heuristic weaknesses.

Traditional algorithm testing commonly employs either randomly generated inputs or test cases specifically designed by human experts. Random inputs offer broad coverage but lack focus on boundary conditions where heuristics often fail. Hand-crafted inputs, while targeted, are limited by the scope of human intuition and may not adequately explore the input space. FunSearch, in contrast, utilizes Large Language Models to systematically generate adversarial instances, iteratively refining them to maximize the probability of exposing weaknesses. This LLM-driven approach allows for a more exhaustive and automated evaluation, surpassing the limitations of both random and hand-crafted testing methods by probing a wider range of potentially problematic inputs and focusing on areas where performance is most sensitive.

The Illusion of Control: Human-LLM Collaboration for Robustness

CoFunSearch builds upon the automated adversarial instance generation of FunSearch by incorporating human feedback into the process. Rather than relying solely on algorithmic mutation and selection, CoFunSearch allows human experts to review and refine instances proposed by the Large Language Model (LLM). This human-in-the-loop approach ensures generated instances are not only challenging for the system under test, but also represent meaningful and realistic scenarios. The integration of human expertise facilitates the discovery of more effective adversarial examples and provides a more nuanced understanding of system vulnerabilities than purely automated methods.

The CoFunSearch framework incorporates human refinement of instances initially generated by a Large Language Model (LLM) to improve the robustness of heuristic searches. This process ensures generated test cases are not only adversarial – meaning they challenge the LLM – but also meaningful, representing realistic and relevant scenarios. Human feedback allows for correction of syntactically valid but semantically nonsensical instances produced by the LLM, and facilitates the steering of the search towards more informative and diverse test cases, ultimately leading to a more thorough evaluation of the heuristic’s performance across a broader range of inputs.

The integration of human expertise within the CoFunSearch framework enables a more nuanced analysis of heuristic performance. By refining LLM-generated adversarial instances, human input facilitates the identification of specific failure modes and areas for improvement within the heuristic algorithm. This process extends beyond simple error detection, allowing for the construction of Pareto Sets – sets of solutions where no single solution can improve on all objectives without worsening at least one other. The identification of these sets provides a detailed understanding of the trade-offs inherent in the heuristic’s design, enabling developers to make informed decisions about optimization strategies and algorithm refinement, moving beyond simply maximizing a single metric.

CoFunSearch employs lower bound calculations as a key component of its search strategy, enabling evaluation of generated test case solution quality and efficient direction of the search process. For the Bin Packing Problem, this implementation resulted in an improved lower bound of 1.5, representing a measurable increase over the prior value of 1.3. This improvement indicates a more accurate assessment of optimal solution proximity and facilitates the discovery of more challenging and informative adversarial instances during the robustness testing phase. The lower bound serves as a heuristic to prioritize exploration of promising areas within the search space, contributing to a more effective and targeted approach.

Revealing the Limits of Approximation

Investigations utilizing CoFunSearch and FunSearch methodologies on established combinatorial problems, such as the Bin Packing Problem, provide valuable insight into the practical performance of common algorithmic approaches. Specifically, analysis of the Best-Fit Heuristic – a simple, yet frequently employed strategy for bin packing – demonstrates how its efficiency is intricately linked to the order in which items are presented. These search techniques allow researchers to systematically explore a vast solution space, revealing not just if an algorithm performs well on average, but how its performance fluctuates under different input conditions, and identifying specific instances where its limitations become apparent. This granular level of analysis moves beyond abstract theoretical guarantees and provides a more realistic assessment of an algorithm’s suitability for real-world applications, allowing for targeted improvements and the development of more robust solutions.

The efficacy of the Best-Fit Heuristic, commonly used in optimization problems like bin packing, is surprisingly sensitive to the sequence in which items are presented. Research demonstrates that a seemingly simple change in input order can drastically alter the algorithm’s performance, leading to significantly different outcomes in terms of resource utilization and efficiency. To account for this variability, computational studies increasingly employ the Random Order Model, which systematically evaluates the heuristic across a multitude of randomly shuffled input sequences. This approach provides a more robust and realistic assessment of the algorithm’s average-case behavior, mitigating the risk of drawing misleading conclusions based on a single, potentially favorable, input arrangement. Understanding this dependence on input order is crucial for accurately characterizing algorithm performance and designing more reliable solutions to complex optimization challenges.

Investigations into the complexities of kk-Median Clustering, facilitated by computational techniques, have recently unveiled a fundamental limitation regarding hierarchical approaches to this optimization problem. Analysis demonstrates the existence of a “Price of Hierarchy,” quantifying the incurred cost of relying on hierarchical solutions, and establishing a non-trivial lower bound of approximately 1.618 – the Golden Ratio. This finding significantly challenges long-held assumptions within the field and, crucially, disproves the previously proposed conjecture that the Nemhauser-Ullmann heuristic, a widely used algorithm for kk-Median Clustering, possesses an output-polynomial running time, prompting a reassessment of its efficiency and scalability.

The pursuit of adversarial instances, as detailed within the study, isn’t about breaking heuristics – it’s about revealing their inherent limitations and prompting evolution. It echoes a sentiment once expressed by Carl Friedrich Gauss: “I would rather be lucky than clever.” This isn’t a dismissal of ingenuity, but a recognition that even the most meticulously crafted systems operate within a probabilistic landscape. Co-FunSearch, by deliberately introducing ‘difficulty,’ doesn’t seek control over the problem space-a control that is, after all, illusory-but rather facilitates a natural selection process. Each adversarial instance is a stress test, a prophecy of potential failure that, in turn, cultivates resilience and informs future iterations. The system, ultimately, begins fixing itself.

What Lies Ahead?

The pursuit of adversarial instances, as demonstrated by this work, isn’t a quest for robust heuristics-it’s an exercise in controlled demolition. Each discovered weakness isn’t a bug, but a prophecy of eventual failure, meticulously revealed. The collaborative approach, blending human intuition with the generative power of large language models, merely accelerates the inevitable entropy. The true challenge isn’t solving these combinatorial problems, but understanding the shapes into which their solutions will degrade.

Current methods treat heuristics as static entities, seeking to patch vulnerabilities as they appear. This is akin to building sandcastles against the tide. The focus must shift to cultivating adaptable heuristics-systems that anticipate their own obsolescence and evolve accordingly. Long stability, the hallmark of current approaches, is the most reliable indicator of a catastrophic, hidden failure mode. The next iteration of research won’t be about finding better solutions, but about designing systems that gracefully accept their own limitations.

The interplay between human and artificial intelligence offers a glimpse of this future, but it’s a precarious balance. The danger lies in mistaking the model’s creativity for genuine understanding. These tools do not reason about complexity; they reflect it. The true metric of success won’t be improved lower bounds, but a deeper comprehension of the landscapes where solutions inevitably crumble.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.16849.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 39th Developer Notes: 2.5th Anniversary Update

- Gold Rate Forecast

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- TON PREDICTION. TON cryptocurrency

- Bitcoin’s Bizarre Ballet: Hyper’s $20M Gamble & Why Your Grandma Will Buy BTC (Spoiler: She Won’t)

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Nikki Glaser Explains Why She Cut ICE, Trump, and Brad Pitt Jokes From the Golden Globes

- Ephemeral Engines: A Triptych of Tech

- AI Stocks: A Slightly Less Terrifying Investment

- 20 Games With Satisfying Destruction Mechanics

2026-01-26 09:11