Author: Denis Avetisyan

Researchers have developed a novel theoretical framework for understanding how noise affects the complex dynamics of recurrent neural networks.

This work introduces the Gaussian Equivalent Method, a mean field theory for analyzing stochastic dynamical systems with nonlinear noise, offering an alternative to perturbative approaches.

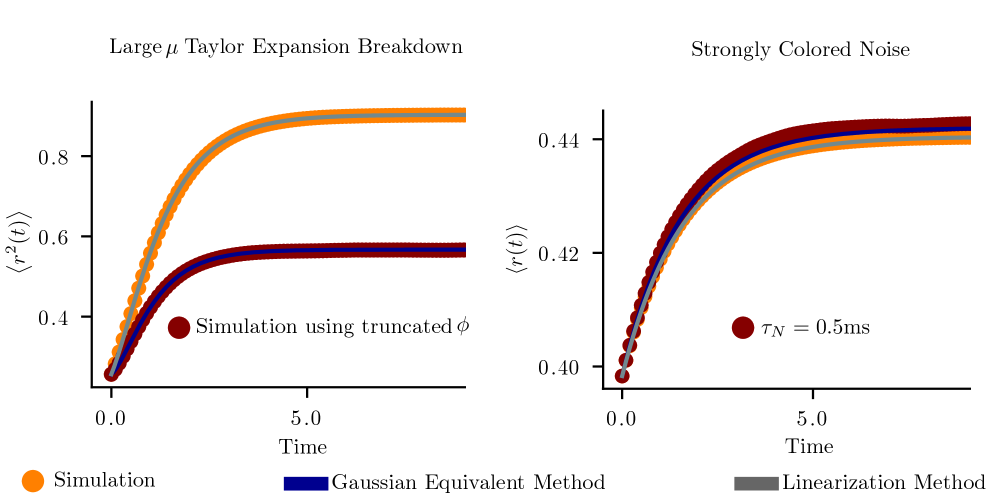

Analyzing recurrent neuronal networks is complicated by the fact that strong, correlated noise often passes through nonlinear functions, challenging traditional dynamical mean-field approaches. This is addressed in ‘Dynamic Mean Field Theories for Nonlinear Noise in Recurrent Neuronal Networks’, which introduces a novel method-the Gaussian Equivalent Method (GEM)-to approximate nonlinear noise with a matched Gaussian process and a lognormal moment closure. The resulting closed-form theory accurately captures order-one transients, fixed points, and noise-induced shifts in bifurcation structure, outperforming linearization-based approximations in regimes of strong fluctuation. Could this approach provide a broadly applicable framework for analyzing noise-dependent phase diagrams in other complex stochastic dynamical systems beyond neuroscience?

Beyond Straight Lines: Why Linear Models Fail the Brain

Conventional mean-field theory, a workhorse for simplifying the analysis of large neural networks, frequently employs linear approximations to make calculations tractable. However, this simplification can obscure crucial aspects of neural dynamics, as brain activity is inherently nonlinear. These linearizations often fail to capture phenomena like bursting, bistability, and complex oscillations – hallmarks of rich neural computation. The brain doesn’t operate on straight lines; its responses exhibit saturation, adaptation, and complex interactions between neurons. Consequently, models based solely on linear assumptions may predict inaccurate or incomplete representations of population activity, hindering a comprehensive understanding of how neural circuits process information and generate behavior. More sophisticated approaches, capable of capturing these nonlinearities, are therefore essential for building realistic and predictive models of brain function.

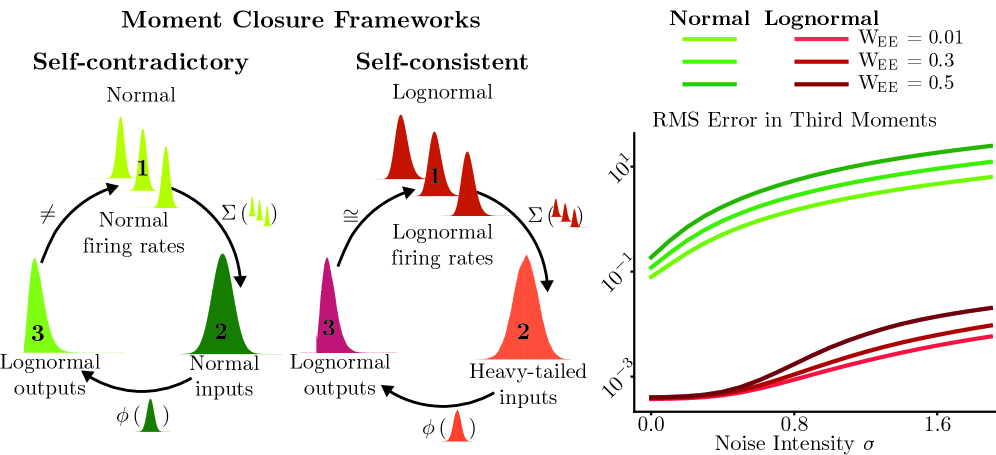

Understanding how populations of neurons interact hinges on precisely characterizing the distribution of their firing rates, a task far more complex than traditional models often allow. Simple assumptions, such as Poisson statistics or Gaussian approximations, frequently fail to capture the nuanced patterns observed in real neural networks – patterns that include skewness, multimodality, and heavy tails. These deviations from standard distributions aren’t merely statistical quirks; they directly influence the collective behavior of the network, impacting information processing and coding efficiency. Consequently, researchers are increasingly employing more sophisticated mathematical frameworks – including density-dependent kernels and non-Gaussian distributions – to model these firing rate distributions accurately. Capturing these subtleties is vital for building biologically realistic models and ultimately deciphering the neural code, moving beyond approximations to reveal the true complexity of population dynamics.

Neural systems are inherently stochastic, and while random, uncorrelated noise is often assumed in simplified models, real neural circuits experience significant correlated noise. This arises from shared synaptic inputs, common network fluctuations, and the limited number of input channels converging on a neuron. Consequently, seemingly minor correlations can dramatically alter population dynamics, shifting the system’s response from predictable to chaotic, and influencing both the precision and reliability of neural coding. Accurately capturing these correlations is therefore paramount; ignoring them can lead to substantial misinterpretations of neural information processing, as the resulting dynamics may diverge considerably from observed biological activity. Sophisticated modeling approaches are increasingly focused on incorporating these dependencies to better reflect the complex interplay of noise and signal in the brain, offering a more nuanced understanding of how neural circuits function and generate behavior.

Escaping Linearization: A Non-Perturbative Solution

The Gaussian Equivalent Method addresses the limitations of traditional mean-field theory by providing a non-perturbative approach to handling nonlinear dependencies of noise. Conventional mean-field analyses often rely on perturbative expansions around a stable fixed point, which can fail when noise correlations are strong or when the system exhibits significant fluctuations. This method circumvents these limitations by directly approximating the nonlinear noise terms with equivalent Gaussian processes that preserve key statistical properties, such as the mean and variance, without requiring small-noise assumptions. Consequently, it offers a more accurate representation of the system’s dynamics, particularly in regimes where perturbative methods are unreliable, and allows for the investigation of phenomena that are masked by linearization procedures.

The Gaussian Equivalent Method leverages the Ornstein-Uhlenbeck (OU) process – a stochastic process describing the velocity of a particle undergoing Brownian motion – to approximate the temporal correlations inherent in neural activity. This process is characterized by a tendency towards a mean value, with fluctuations governed by a normally distributed random variable. Critically, the method models the distribution of neural activity, which is often non-Gaussian, using a log-normal distribution derived from the OU process. This transformation allows for analytical tractability; while neural firing rates themselves may not be normally distributed, their logarithm is, enabling the application of Gaussian statistics to represent stochastic fluctuations in neural dynamics. The log-normal representation accurately captures the skewness observed in neuronal firing rate distributions, offering a more realistic depiction of neural variability than purely Gaussian approximations.

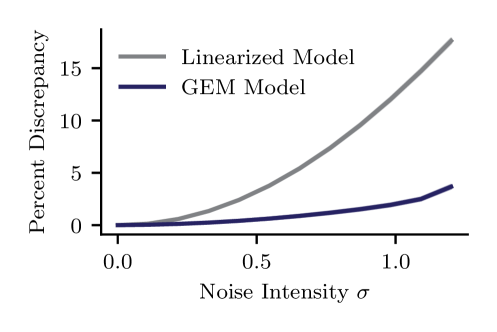

The Gaussian Equivalent Method simplifies the analysis of nonlinear stochastic systems by approximating complex, non-Gaussian noise terms with their Gaussian counterparts. This substitution allows for the application of computationally efficient techniques derived from Gaussian process theory, which would otherwise be intractable with the original noise distribution. Specifically, this approach facilitates the calculation of system dynamics, particularly during transient periods, with demonstrably higher accuracy than traditional linearization methods. Linearization often fails to capture the full range of stochastic fluctuations, while the Gaussian Equivalent Method provides a more faithful representation of the system’s response to noise, even when the underlying noise is significantly non-Gaussian. This is achieved without requiring perturbative expansions, which can introduce errors and limit the validity of the results.

Stable States and Responses: Validating the Approach

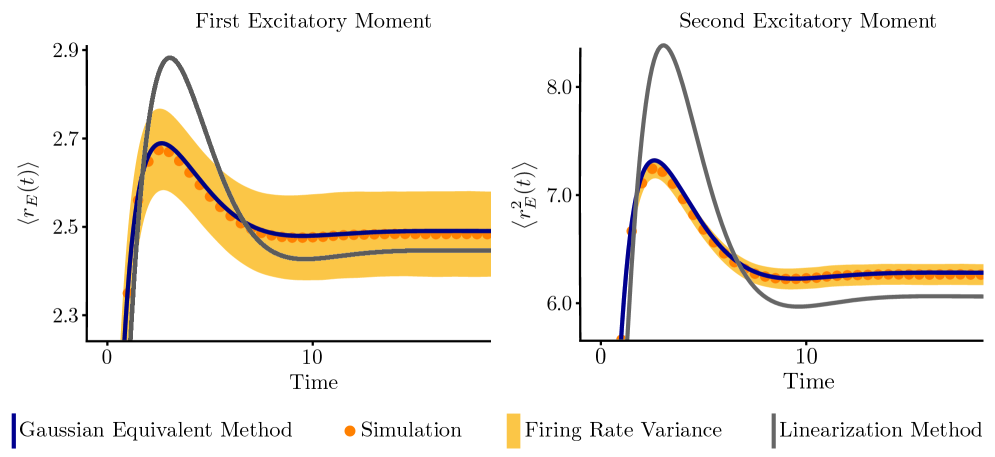

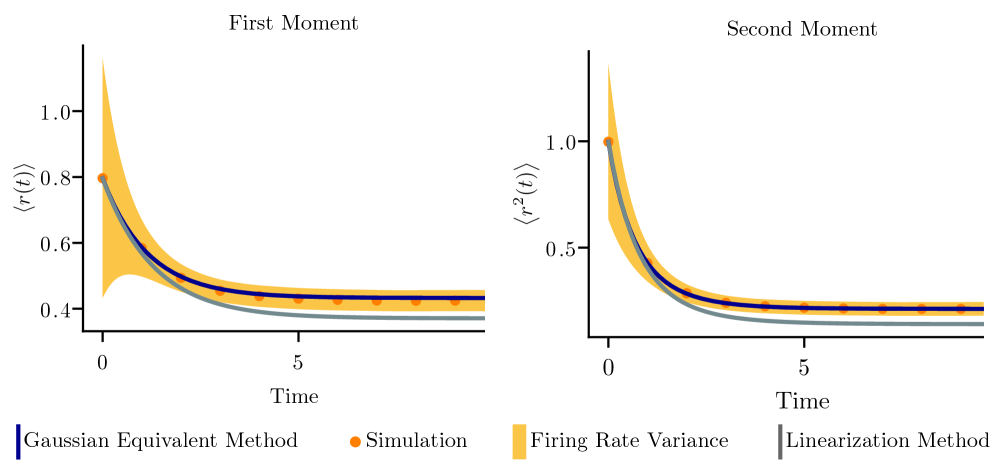

This methodology enables the precise determination of fixed points within the modeled neural population, representing stable equilibrium states. These fixed points are identified as the conditions where the rate of change in neural activity reaches zero, indicating a balanced state. The accuracy of fixed point determination relies on iterative numerical solvers applied to the system’s governing equations, allowing for the characterization of both excitatory and inhibitory balance. Identified stable states correspond to persistent patterns of activity, providing a baseline for understanding how the neural population maintains information or prepares for subsequent stimuli. The number and characteristics of these stable states are dependent on network parameters, such as synaptic weights and external input.

Characterizing transient system behavior-the response to stimuli prior to reaching a stable state-provides crucial insight into neural information processing dynamics. This methodology allows for the analysis of how the system evolves over time, revealing the intermediate states and pathways taken during computation. Importantly, models utilizing this approach demonstrate a reduced Root Mean Square Error (RMSE) when compared to traditional linear models, indicating improved accuracy in predicting system responses. The lower RMSE values suggest that the non-linear dynamics captured by this method are essential for accurately representing the complexities of neural system behavior and outperform the simplifying assumptions of linear approximations.

The methodological accuracy of this system analysis is mathematically substantiated by Isserlis’ theorem, specifically concerning the calculation of moments of normally distributed random variables. This theorem allows for the validation of approximations made when assuming a log-normal distribution to model system behavior. By demonstrating the consistency between calculations derived from the assumed log-normal distribution and those predicted by Isserlis’ theorem for normal distributions, the approach confirms the validity of utilizing the log-normal distribution as a representative model for the observed neural population dynamics, and provides a means of quantifying the error introduced by this approximation.

Beyond Simple Sums: The Reality of Nonlinear Dynamics

Neural systems rarely respond to stimuli in a simple, linear fashion; instead, the relationship between input and the resulting output – described by the transfer function – frequently demonstrates power-law behavior. This isn’t merely a quirk of biological systems, but a signature of fundamental nonlinearity, where a small change in input can trigger a disproportionately large – or small – response. y = ax^k represents this power-law relationship, where ‘y’ is the output, ‘x’ is the input, ‘a’ is a constant, and ‘k’ is the exponent defining the nonlinearity. Such nonlinearities are critical because they allow neural circuits to perform sophisticated computations, like amplifying weak signals, detecting subtle differences, and implementing diverse coding strategies beyond what a linear system could achieve, ultimately shaping how information is represented and processed within the brain.

Neural populations don’t simply relay information linearly; the relationship between input stimuli and resulting neural responses is fundamentally nonlinear. This nonlinearity profoundly impacts how information is processed and encoded, meaning a simple summation of neuronal activity fails to capture the full computational power of the network. The presented approach effectively models these deviations from linearity, revealing that subtle distortions in the input-output relationship can dramatically alter the encoded information. Consequently, the brain isn’t merely a passive receiver of signals, but an active transformer, capable of sophisticated computations due to these inherent nonlinearities-allowing for a richer, more nuanced representation of the external world than would be possible with a linear system.

A more nuanced understanding of neural computation emerges when acknowledging the inherent nonlinearities within biological systems. Traditional models often rely on linear approximations, which can obscure the true complexity of information processing; however, recent research demonstrates that neural populations encode and transmit information through distinctly nonlinear transfer functions, frequently exhibiting power-law behavior. This approach not only enhances the realism of computational models, but also reveals a remarkable capacity for complex information processing – crucially, the degree of information loss during this processing diminishes as the sample size increases, with the Information Loss Ratio converging towards zero. This suggests that, given sufficient data, the system’s ability to accurately represent and transmit information approaches an ideal limit, offering a compelling pathway towards decoding the intricate mechanisms underlying neural computation.

The pursuit of elegant theory often collides with the messy reality of implementation. This paper’s Gaussian Equivalent Method, a novel mean field theory for handling nonlinear noise, feels less like a revolution and more like a sophisticated workaround. It acknowledges that perturbative approaches falter when noise dominates – a painfully familiar situation. The study’s focus on stochastic dynamical systems highlights a truth often obscured by theoretical neatness: production environments rarely conform to idealized models. As Carl Sagan once observed, “Somewhere, something incredible is waiting to be known.” But knowing isn’t enough; it’s the inevitable patching and refactoring that truly defines the lifespan of any system, even one built on a seemingly solid theoretical foundation. This GEM method will undoubtedly require its own set of adjustments once faced with real-world data.

The Road Ahead

This Gaussian Equivalent Method, a new flavor of mean field theory, predictably aims to tame the beast of nonlinear noise. It’s a familiar story; a mathematically elegant attempt to sidestep the truly messy business of simulating actual neurons. One anticipates a flurry of papers demonstrating GEM’s prowess on increasingly contrived network topologies, followed by the inevitable realization that production-level recurrent networks-those sprawling, patched-together things built by people with deadlines-don’t politely adhere to theoretical assumptions. The log-normal distributions GEM favors will likely prove… optimistic, in the face of real-world data.

The promise of moving beyond perturbative approaches is, of course, alluring. But history suggests that each ‘non-perturbative’ method simply trades one set of approximations for another. The core challenge remains: accurately capturing the emergent dynamics of these systems without drowning in computational cost. It’s a bit like building a better map of a forest fire; the map will always be further behind the flames.

One suspects the next iteration won’t be a fundamentally new theory, but rather an increasingly elaborate suite of correction terms, designed to bandage the inevitable discrepancies between GEM’s predictions and experimental observations. Everything new is just the old thing with worse docs, and a slightly more complex codebase.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15462.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- Building 3D Worlds from Words: Is Reinforcement Learning the Key?

- Securing the Agent Ecosystem: Detecting Malicious Workflow Patterns

- The Best Directors of 2025

- Gold Rate Forecast

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Mel Gibson, 69, and Rosalind Ross, 35, Call It Quits After Nearly a Decade: “It’s Sad To End This Chapter in our Lives”

- 20 Best TV Shows Featuring All-White Casts You Should See

- TV Shows Where Asian Representation Felt Like Stereotype Checklists

- Umamusume: Gold Ship build guide

- Top 20 Educational Video Games

2026-01-25 01:06