Author: Denis Avetisyan

Ecologists can now build custom machine learning models for image-based wildlife monitoring without needing extensive coding expertise or massive datasets.

This review details a lightweight and accessible machine learning pipeline, demonstrated with successful age and sex classification of red deer from camera trap images using transfer learning and active learning techniques.

While increasingly vital for ecological monitoring, applying machine learning to image-based wildlife data often requires specialized expertise and reliance on generalized models. This limitation is addressed in ‘Beyond Off-the-Shelf Models: A Lightweight and Accessible Machine Learning Pipeline for Ecologists Working with Image Data’, which introduces a user-friendly pipeline enabling ecologists to independently build and iterate on custom image classifiers. Demonstrated through successful age and sex classification of red deer from camera trap images-achieving 90.77% and 96.15% accuracy respectively-this framework empowers researchers to tailor models to specific datasets and research questions. Could this accessible approach unlock broader adoption of machine learning for detailed demographic analysis and ultimately, more effective wildlife conservation efforts?

The Data Deluge: Unlocking Insights from the Wild

The efficacy of modern wildlife monitoring is increasingly dependent on the analysis of images captured by a growing network of camera traps, yet this reliance presents a significant logistical challenge. These devices generate immense datasets – often numbering in the millions of images per year, per study – and traditionally, extracting meaningful information required painstaking manual annotation. This process, involving humans identifying and categorizing animals within each image, is not only exceptionally time-consuming but also carries a substantial financial burden, limiting the scale and frequency of crucial biodiversity assessments. The sheer volume of imagery quickly overwhelms available resources, creating a data bottleneck that impedes timely insights into population trends, species distribution, and the effectiveness of conservation strategies. Consequently, advancements in automated image analysis are essential to unlock the full potential of camera trap data and accelerate wildlife research.

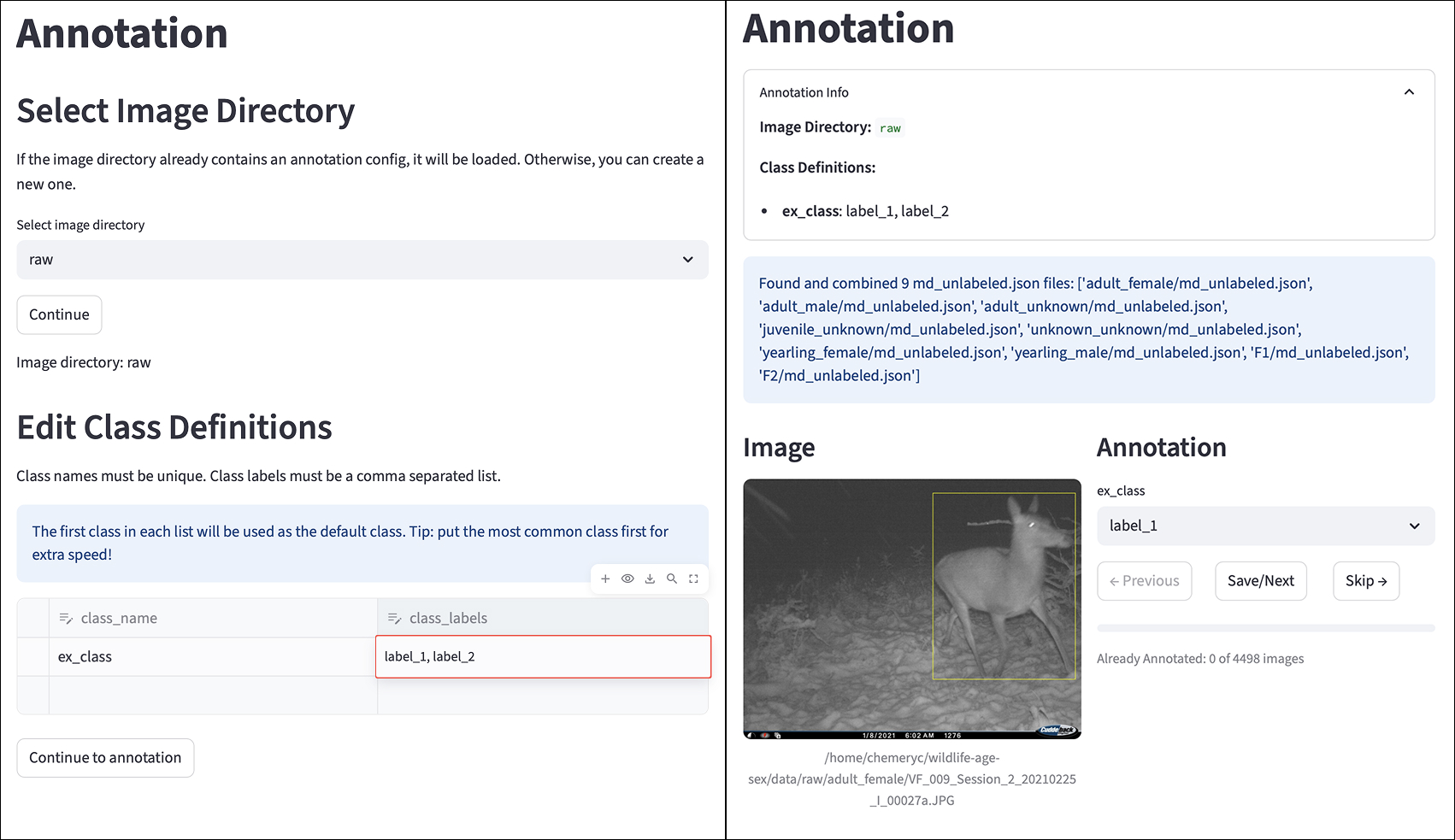

Accurate identification of animals within camera trap images begins with reliable bounding box detection – the process of digitally outlining each animal present. This localization step provides regions of interest which are then used for subsequent analyses, such as species identification and individual recognition, and depends on correctly localized subjects. A leading tool in this endeavor is MegaDetector, an algorithm designed to efficiently scan large datasets and automatically draw these bounding boxes. While not infallible, MegaDetector significantly reduces the burden of manual annotation, allowing researchers to process images at a scale previously unattainable and paving the way for more timely and informed conservation decisions. The precision of these bounding boxes directly influences the accuracy of downstream tasks, making this automated detection a critical component of modern wildlife monitoring efforts.

The escalating volume of data generated by modern wildlife monitoring presents a significant impediment to conservation. While camera trap technology offers unprecedented opportunities to study animal populations, the sheer quantity of images-often numbering in the millions per year from a single study-overwhelms traditional analytical methods. This data bottleneck delays crucial insights into population trends, species distribution, and the effectiveness of conservation strategies. Consequently, researchers face extended processing times, limiting their ability to respond quickly to emerging threats, such as habitat loss or poaching. The lag between data collection and actionable knowledge hinders adaptive management, potentially undermining conservation efforts that require timely interventions to protect vulnerable species and ecosystems.

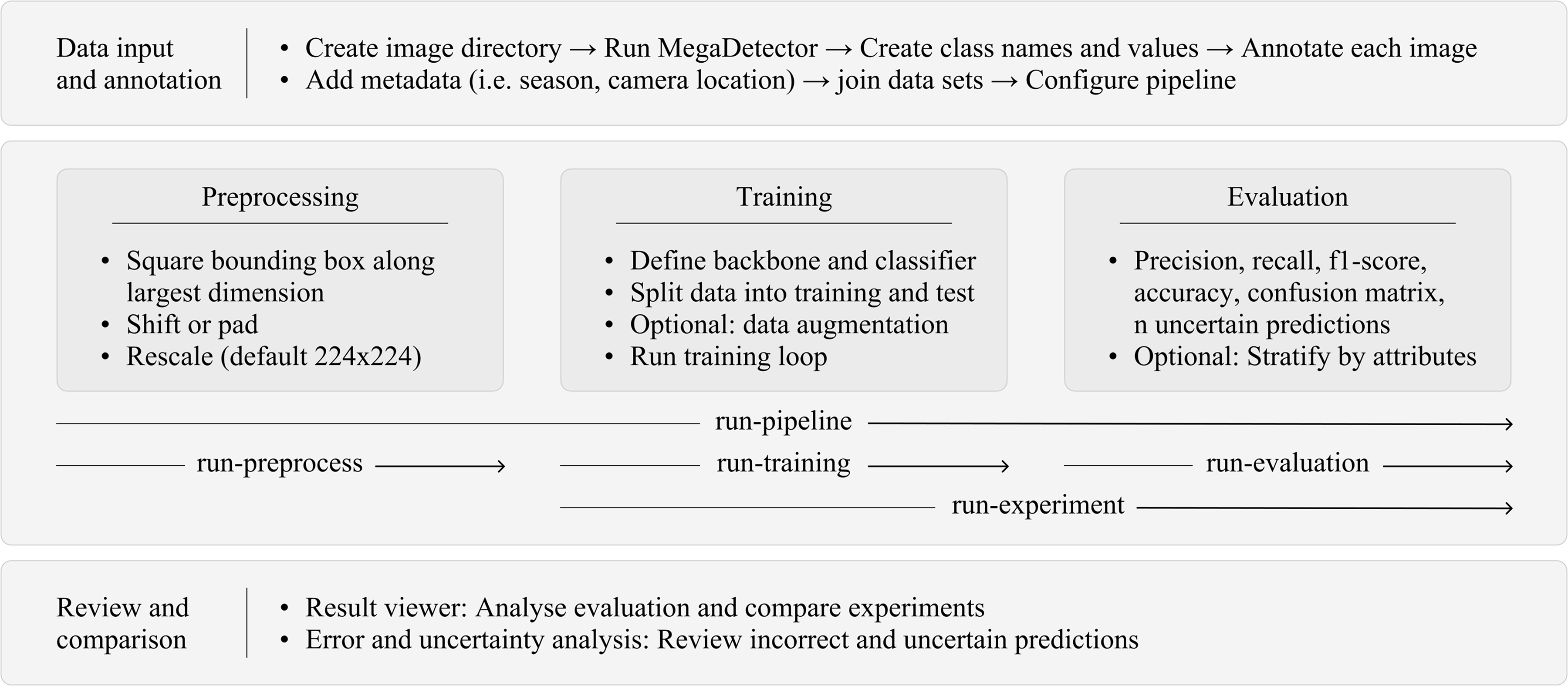

The Automated Sentinel: A Classification Pipeline

The Classification Pipeline functions by initially employing bounding box detection to locate animals within images or video frames. This localization step provides regions of interest which are then fed into deep learning models for subsequent classification. The integration of these two processes automates the identification of animal species, eliminating the need for manual annotation and reducing processing time. Bounding box detection ensures that the classification model focuses on the animal itself, improving accuracy and minimizing false positives caused by background elements. The pipeline supports various bounding box detection algorithms, allowing for optimization based on specific environmental conditions and animal characteristics.

The classification pipeline leverages pre-trained convolutional neural networks (CNNs) as feature extraction backbones to optimize both processing speed and classification accuracy. Specifically, ResNet50, VGG19, DenseNet161, and DenseNet201 architectures are employed; these networks have been pre-trained on large image datasets, enabling transfer learning and reducing the need for extensive training from scratch. ResNet50 provides a balance between performance and computational cost, while VGG19, though deeper, offers established performance. DenseNet161 and DenseNet201 utilize dense connections to enhance feature propagation and improve accuracy, albeit at a higher computational expense. The selection of a specific backbone depends on the required trade-off between speed and accuracy for the specific application.

Data augmentation is implemented within the classification pipeline to artificially expand the training dataset, enhancing model robustness and generalization performance, especially when faced with limited real-world data. Techniques employed include random horizontal and vertical flips, rotations within a defined degree range, random brightness and contrast adjustments, and small-scale translations. These transformations create modified versions of existing images, effectively increasing the dataset size and exposing the model to a wider variety of image variations. This process reduces overfitting and improves the model’s ability to accurately classify images captured under different conditions or with slight variations in animal pose and appearance.

The Classification Pipeline utilizes a TOML Configuration File to define all parameters governing model training and evaluation, ensuring complete reproducibility of results. This file specifies the chosen model architecture – including options such as ResNet50, VGG19, DenseNet161, and DenseNet201 – alongside associated hyperparameters like learning rate, batch size, and the number of training epochs. By externalizing these parameters, the pipeline allows for systematic experimentation with different configurations without requiring code modifications, and provides a clear record of the exact settings used to generate any given result. This configuration-driven approach facilitates collaborative research and simplifies the process of comparing model performance across varied settings.

Decoding the Wild: Demographic Insights

The automated pipeline successfully categorizes Red Deer individuals into distinct age and sex classes, generating key demographic data for population monitoring and management. Age classification distinguishes between juvenile and adult animals, while sex classification identifies males and females. This classification is achieved through machine learning models trained on image data, enabling large-scale demographic assessments that would be impractical with traditional methods. The resulting data informs conservation strategies by providing insights into population structure, reproductive rates, and overall population health.

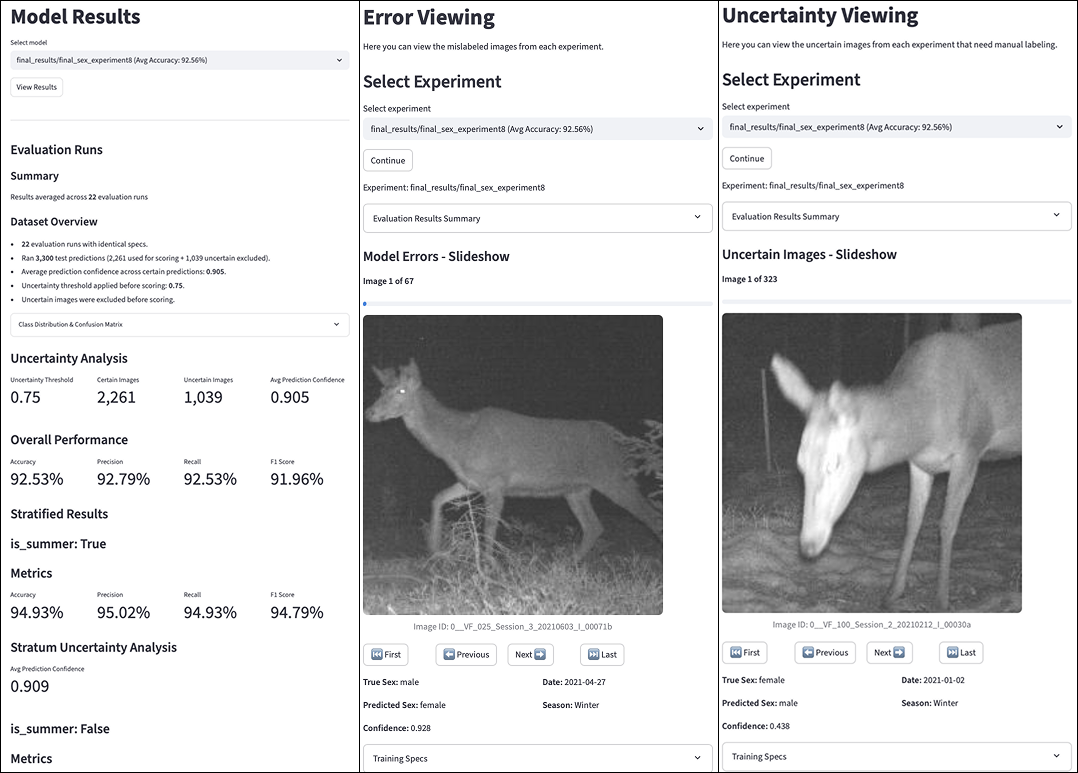

The prediction pipeline incorporates both confidence and uncertainty thresholds to maintain data reliability. Predictions generated by the model are assessed against a predetermined confidence threshold; results falling below this threshold are discarded as unreliable. Simultaneously, an uncertainty threshold is applied, filtering predictions where the model expresses significant doubt in its assessment. This dual-threshold system minimizes the inclusion of low-quality data in subsequent analyses, ensuring the demographic insights derived from age and sex classification are based on high-confidence predictions.

The implemented Streamlit user interface facilitates comprehensive review of model predictions for both age and sex classification of red deer. This interface allows users to visually inspect individual predictions alongside input imagery, enabling detailed error analysis and identification of potential failure modes. Furthermore, the UI supports comparison of performance metrics between different model versions or configurations, streamlining the model selection process and allowing for iterative improvement based on observed results. This functionality is crucial for validating model accuracy and ensuring the reliability of demographic data used for conservation management.

The red deer classification pipeline demonstrates high performance in both age and sex identification. Overall accuracy reached 90.68% for age classification and 92.53% for sex classification. Detailed evaluation of age classification yielded a precision of 82.22%, a recall of 90.68%, and an F1-score of 86.24%. Sex classification resulted in a precision of 92.79%, a recall of 92.53%, and an F1-score of 91.96%. These metrics indicate a robust ability to accurately categorize red deer by age and sex, providing valuable data for conservation management strategies.

The Art of Persuasion: Optimizing Annotation with Active Learning

An Active Learning Pipeline was implemented to address the substantial costs associated with image annotation and simultaneously enhance model performance. This iterative process moves beyond random data selection, instead prioritizing images that will yield the greatest improvement in the model’s understanding. By intelligently choosing which data points require manual labeling, the pipeline minimizes the total annotation effort needed to achieve a desired level of accuracy. This focused approach not only reduces financial expenditure but also accelerates the training process, as the model learns more effectively from the most informative examples, ultimately leading to a more robust and reliable system.

The efficiency of image annotation was markedly improved through a pipeline designed to prioritize the most valuable data for labeling. Rather than randomly selecting images, the system intelligently identifies those where the model exhibits the greatest uncertainty in its predictions. This focus on ‘difficult’ examples-those the model struggles to classify correctly-allows for targeted annotation, maximizing the impact of each labeled image. By concentrating effort on refining the model’s understanding of ambiguous cases, the pipeline accelerates the learning process and achieves higher accuracy with a significantly reduced annotation workload. This strategic selection ensures that limited annotation resources are deployed where they yield the greatest benefit, ultimately leading to a more robust and reliable model.

The integration of task-specific experts into the active learning pipeline dramatically enhances animal classification accuracy. Rather than relying on a single, generalized model, the system consults specialized algorithms trained to recognize particular animal features – such as subtle variations in plumage, distinctive body shapes, or unique behavioral patterns. This collaborative approach allows the model to focus on nuanced details often missed by broader analyses, effectively resolving ambiguities and reducing misclassifications. By channeling expertise directly into the annotation process, the system prioritizes images requiring refined discernment, leading to a more robust and reliable animal identification capability with fewer labeled examples.

A key benefit of the implemented active learning pipeline lies in its ability to drastically curtail the demands on manual annotation efforts. By intelligently prioritizing images that pose the greatest challenge to the model – those where prediction confidence is low – the system focuses labeling resources where they yield the most significant performance gains. This strategic selection minimizes the need for exhaustive, full-dataset annotation, representing a substantial cost and time savings. Consequently, the efficiency of data labeling is markedly improved, accelerating the model training process and allowing for quicker iteration and refinement of animal classification accuracy. The reduced annotation burden unlocks the potential for deploying machine learning solutions in scenarios previously constrained by resource limitations.

The pursuit of bespoke models, as detailed in this work regarding red deer classification, echoes a deeper truth: data are shadows, and models are ways to measure the darkness. It is not enough to simply apply pre-trained foundations; true understanding demands a sculpting of the algorithm to the unique contours of the observed world. This pipeline doesn’t promise perfect accuracy-that’s a pretty coincidence-but rather a persuasive conversation with the chaos inherent in camera trap imagery. Fei-Fei Li once said, “AI is not about replacing humans; it’s about augmenting our capabilities.” This sentiment underpins the entire endeavor; the pipeline seeks not to automate ecological understanding, but to amplify the insights gleaned from diligent observation, allowing researchers to ask more nuanced questions of the wilderness it captures.

What Lies Beyond?

The pursuit of elegant pipelines, even those built on the ostensibly firm ground of transfer learning, feels less like engineering and more like carefully arranging pebbles against a tide. This work demonstrates a method – a spell, if one prefers – for coaxing reasonable classification from the chaotic flood of camera trap imagery. But the true challenge isn’t achieving high accuracy on a curated dataset; it’s maintaining that illusion of order when confronted with the infinite variability of the natural world. The ghosts in the data-poor lighting, obscured subjects, novel poses-will always be more numerous than the signals.

Future iterations will inevitably chase ever-larger foundation models, seeking the perfect pre-trained weight configuration. This feels… optimistic. Perhaps the deeper gains lie not in bigger models, but in more nuanced approaches to the inevitable failures. Active learning, as presented, offers a path, but it’s a reactive measure. A proactive strategy might embrace uncertainty, building models that know what they don’t know, and flag those instances for human review – accepting that complete automation is a beautiful, yet ultimately unattainable, lie.

The question isn’t simply “can a machine classify a deer?” but “what does it mean when it thinks it has?” Noise isn’t a bug; it’s truth wearing a mask of low confidence. The next step isn’t about building a better classifier, but about building a better listener – one that can discern the whispers of chaos from the pronouncements of certainty.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.15813.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 39th Developer Notes: 2.5th Anniversary Update

- Gold Rate Forecast

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- TON PREDICTION. TON cryptocurrency

- Bitcoin’s Bizarre Ballet: Hyper’s $20M Gamble & Why Your Grandma Will Buy BTC (Spoiler: She Won’t)

- Celebs Who Fake Apologies After Getting Caught in Lies

- Nikki Glaser Explains Why She Cut ICE, Trump, and Brad Pitt Jokes From the Golden Globes

- The 35 Most Underrated Actresses Today, Ranked

- Rivian: A Most Peculiar Prospect

- A Golden Dilemma: Prudence or Parity?

2026-01-24 06:43