Author: Denis Avetisyan

The stunning abilities of modern language models aren’t evidence of understanding, but rather a testament to the power of pattern recognition and data compression.

This review argues that large language models demonstrate ‘unreasonable effectiveness’ through advanced statistical pattern matching rather than genuine cognitive ability.

Despite ongoing debate about the nature of intelligence in artificial systems, large language models (LLMs) continue to exhibit surprising capabilities-abilities that challenge simple characterizations of these systems as mere mimicry or data recall. This paper, ‘The unreasonable effectiveness of pattern matching’, investigates this phenomenon by demonstrating an LLM’s remarkable aptitude for interpreting structurally coherent “Jabberwocky” language-text where content words are replaced with nonsense-suggesting a powerful capacity for recovering meaning from patterns alone. The core finding is that this ability isn’t evidence of genuine understanding, but rather highlights the unexpectedly potent role of pattern matching and compression in LLM performance. If meaning can be extracted from structure alone, what does this imply about the relationship between pattern recognition and intelligence itself?

The Limits of Pattern Recognition

Large language models, prominently including systems like ChatGPT, demonstrate a remarkable aptitude for discerning and reproducing patterns present within vast textual datasets. This proficiency, however, frequently operates without genuine comprehension of the content’s meaning or the concepts it represents. These models excel at predicting the most probable continuation of a given text sequence, effectively mastering statistical relationships between words and phrases. Yet, this skill should not be mistaken for understanding; the models manipulate symbols based on learned correlations, rather than possessing cognitive awareness of the information those symbols convey. Consequently, while capable of generating human-sounding text, they often struggle with tasks demanding nuanced reasoning, common sense, or a grasp of the real-world context underpinning the language.

The remarkable fluency of current large language models often obscures a fundamental limitation: they operate as sophisticated “Stochastic Parrots.” This evocative term highlights the models’ reliance on statistical correlation rather than genuine comprehension. These systems excel at predicting the next word in a sequence, based on patterns learned from massive datasets, effectively mimicking human language without possessing any understanding of the concepts those words represent. While a model might convincingly generate text about complex topics, it does so by stitching together statistically probable word combinations, not by reasoning about the subject matter itself. This creates an illusion of intelligence, masking a lack of semantic grounding and an inability to truly innovate or adapt to novel situations beyond the patterns already encoded within its training data.

The boundaries of current large language models are sharply defined when facing challenges demanding authentic reasoning and an understanding of context. While proficient at identifying and reproducing linguistic patterns, these models often falter when tasked with problems requiring more than surface-level analysis. Studies reveal a distinct inability to extrapolate meaning beyond the statistically probable, demonstrating that correlation, however complex, does not equate to comprehension. This shortfall suggests that advancements beyond simply scaling up pattern recognition – perhaps incorporating mechanisms for causal inference or world modeling – are crucial for achieving genuine artificial intelligence and moving past the limitations of sophisticated mimicry.

Meaning Reconstruction as Compression

Large Language Models (LLMs) exhibit a demonstrable capacity for ‘Meaning Reconstruction,’ which refers to the ability to accurately infer missing or corrupted portions of text. This functionality extends beyond simple pattern completion; LLMs can effectively predict omitted words, phrases, or even entire sentences based on contextual understanding. Performance in tasks such as masked language modeling – where portions of text are intentionally hidden and the model must predict the missing content – provides quantitative evidence of this reconstructive capability. The success of LLMs in these scenarios indicates an internal representation of meaning that allows for effective prediction even with incomplete or degraded input data.

Large Language Models (LLMs) consistently demonstrate the ability to recover obscured information within textual data, a capability proven through performance on masked language modeling tasks. These models are not limited to general knowledge domains; they exhibit proficiency even when reconstructing meaning from text pertaining to specialized and complex fields such as Federal Law. Evaluation metrics consistently show high accuracy rates in predicting masked words or phrases, indicating a robust understanding of contextual relationships and legal terminology. This success extends to scenarios involving significant textual corruption or incomplete information, suggesting LLMs can effectively infer missing data based on surrounding context and learned patterns within the legal domain.

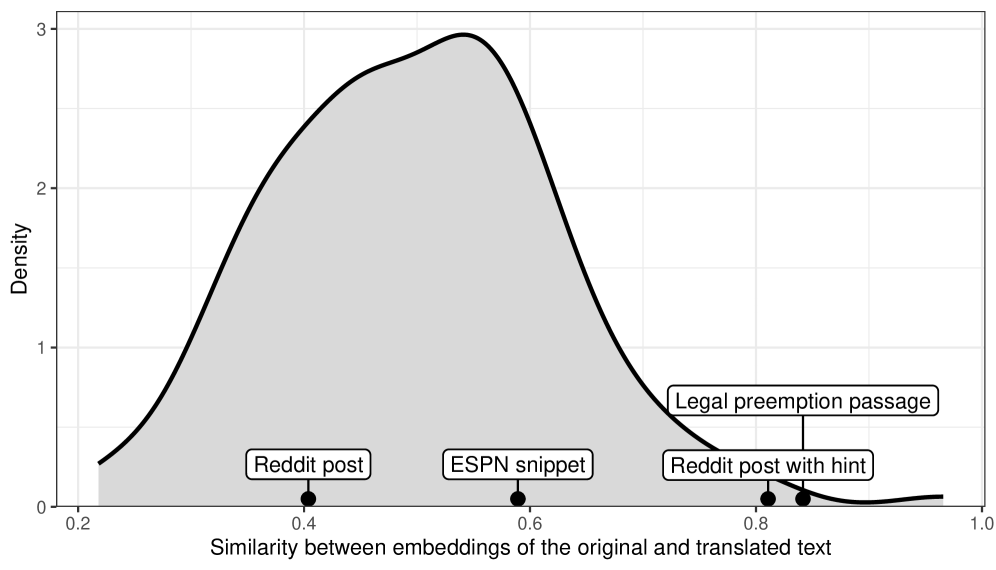

The observed ability of Large Language Models to reconstruct meaning from incomplete or corrupted text shares functional similarities with data compression techniques. In compression, data is reduced to its most essential elements, allowing for efficient storage and transmission, followed by accurate reconstruction upon retrieval. The research detailed in this paper demonstrates this principle through high success rates in translating heavily modified texts, indicating the model doesn’t merely memorize patterns but distills information into a compressed representation capable of faithful reconstruction. This suggests an underlying principle where meaning is not simply processed but represented in a form amenable to both reduction and accurate recovery, mirroring the core function of compression algorithms.

Relational Understanding: Beyond Simple Patterns

Large language models (LLMs) achieve reconstructive text processing not solely through identifying statistical patterns, but through a combined process of pattern matching and contextual understanding. This involves recognizing relationships between patterns – how words relate to each other syntactically and semantically – and interpreting those patterns within the broader context of the text. The models analyze linguistic constructions, encompassing elements from individual words to complete sentence structures, to establish these relationships. This integrated approach allows LLMs to move beyond simple pattern recognition and towards a more nuanced comprehension of text, even when presented with unfamiliar or nonsensical input.

Large Language Models (LLMs) process language not merely through pattern identification, but by establishing relationships between these patterns and their surrounding linguistic context. This relational understanding is facilitated by ‘Constructions’, which encompass a broad spectrum of linguistic structures, from individual words and morphemes to complex syntactic arrangements and discourse-level patterns. LLMs analyze how these constructions interact – how a particular word modifies another, how a phrase functions within a sentence, or how a sentence contributes to the overall meaning of a passage – allowing them to derive meaning beyond simple sequential analysis. The models leverage these relational analyses to predict and generate text that is statistically coherent and contextually appropriate, even when presented with novel or incomplete input.

Large language models exhibit the capacity to process and derive meaning from text lacking semantic coherence, as evidenced by performance on texts like Lewis Carroll’s ‘Jabberwocky’ and within the interactive fiction game ‘Gostak.’ In both cases, LLMs were able to successfully navigate and, in the case of ‘Gostak,’ partially play the game despite the presence of invented words and non-standard linguistic structures. This success isn’t based on recognizing the invented vocabulary, but rather on identifying and applying relational patterns – grammatical structures and contextual cues – to establish relationships between the components of the text, allowing for processing even without traditional semantic understanding.

The Emergence of Unexpected Abilities

Large language models increasingly demonstrate capabilities that weren’t explicitly built into their design, a phenomenon termed ’emergent abilities’. These skills aren’t about recalling memorized data; instead, they stem from the model’s capacity to process incomplete or ambiguous information and reconstruct a coherent understanding. This reconstructive process allows the model to fill in gaps, resolve uncertainties, and generate novel outputs beyond simple pattern matching. Essentially, the ability to navigate informational ambiguity isn’t a bug, but a feature-the foundation upon which more complex behaviors, such as creative writing or logical reasoning, unexpectedly emerge as the model scales in size and complexity.

The surprising capacity of large language models to perform tasks like summarization and code generation isn’t the result of direct instruction, but rather an unexpected consequence of their sheer scale and the way they process information. These ‘emergent abilities’ aren’t explicitly programmed into the system; instead, they arise as the model learns to discern relationships between concepts. By analyzing vast datasets, the model develops an internal representation of knowledge, allowing it to extrapolate and apply understanding to novel situations. This relational understanding isn’t about memorizing patterns, but about grasping the underlying connections between ideas, effectively enabling the model to synthesize information and produce coherent, original outputs – a phenomenon previously thought exclusive to human cognition.

Large language models increasingly exhibit capabilities that extend beyond simple text prediction, hinting at the development of internal representations akin to human comprehension. Rather than solely calculating probabilities for the next word in a sequence, these models appear to construct a relational understanding of information, allowing them to generalize learned patterns to novel situations. This emergent capacity manifests in abilities like summarizing complex texts or even generating functional code, tasks requiring a degree of abstract reasoning previously thought exclusive to human intelligence. While not a perfect analogy, the models’ success in these areas suggests the formation of an internal ‘world model’ – a conceptual framework enabling adaptation and problem-solving beyond rote memorization, and demonstrating a surprising level of cognitive flexibility.

The exploration of Large Language Models, as detailed in the article, reveals a system predicated not on understanding, but on extraordinarily efficient pattern recognition. This aligns perfectly with the sentiment expressed by Carl Friedrich Gauss: “If others would confide in me as much as they confide in their own arithmetic, the world would be a great deal more reasonable.” The LLMs, like complex arithmetic, operate on rules derived from data – identifying and replicating patterns with remarkable fidelity. The article posits that emergent abilities aren’t evidence of intelligence, but a consequence of this powerful compression and pattern matching – a ‘reasonable’ outcome given the scale of the data and the sophistication of the algorithms. It’s a demonstration of what can be achieved through rigorous application of statistical relationships, mirroring Gauss’s belief in the power of precise calculation.

Beyond the Echo

The assertion that current Large Language Models operate primarily via pattern matching, while perhaps unsatisfying to those seeking sentience in silicon, presents a necessary austerity. Further investigation must concentrate not on creating intelligence, but on delineating the boundaries of this remarkably efficient mimicry. The critical question isn’t whether these models ‘understand,’ but rather, what tasks are fundamentally susceptible to solution via sufficiently scaled compression of probabilistic relationships. Unnecessary is violence against attention; speculation on consciousness distracts from the concrete limitations of statistical inference.

A pressing challenge lies in developing metrics that distinguish genuine generalization from sophisticated interpolation. Current benchmarks, often predicated on human linguistic intuitions, prove vulnerable to exploitation by precisely the pattern-matching capabilities this work highlights. Future assessment should prioritize tasks demanding counterfactual reasoning, causal inference, and demonstrable adaptation to genuinely novel situations – areas where brute-force compression is likely to falter.

The field risks circularity if it continues to evaluate models based on outputs indistinguishable from human performance. Density of meaning is the new minimalism. A more fruitful path may involve intentionally limiting model capacity, forcing the emergence of efficient, interpretable representations – and, in doing so, revealing the fundamental constraints on information processing, regardless of substrate.

Original article: https://arxiv.org/pdf/2601.11432.pdf

Contact the author: https://www.linkedin.com/in/avetisyan/

See also:

- 39th Developer Notes: 2.5th Anniversary Update

- Gold Rate Forecast

- The Hidden Treasure in AI Stocks: Alphabet

- If the Stock Market Crashes in 2026, There’s 1 Vanguard ETF I’ll Be Stocking Up On

- TON PREDICTION. TON cryptocurrency

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

- Warby Parker Insider’s Sale Signals Caution for Investors

- Beyond Basic Prompts: Elevating AI’s Emotional Intelligence

- Actors Who Jumped Ship from Loyal Franchises for Quick Cash

- Berkshire After Buffett: A Fortified Position

2026-01-20 16:44