DJs and MCs are a classic pairing in hip-hop. The DJ handles the music, while the MC provides the rhymes, and together they create an incredibly energetic and exciting performance.

At first glance, the rapper (MC) and the DJ in hip-hop seem like very different artists who rely on each other. The MC uses their voice and a microphone, while the DJ uses records and equipment like turntables and mixers.

Despite their different approaches, MCs and DJs frequently share a common aim: to connect with the audience and express themselves creatively, often through the use of sampling.

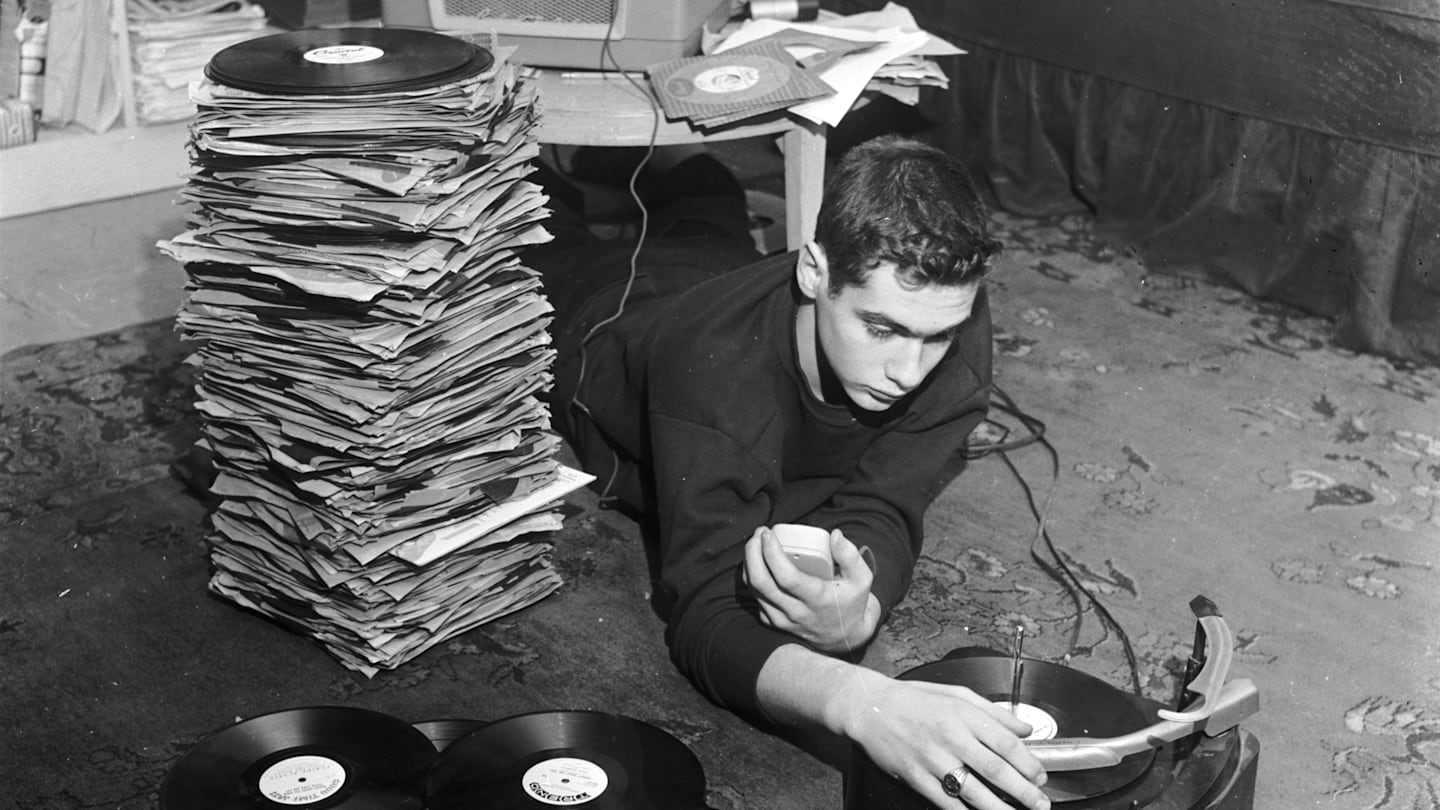

Scratching a record of my life

I think the link between hip-hop and DJing really comes down to a desire for control, starting with the DJ’s ability to command what we hear on the radio.

Douglas “Jocko” Henderson was a highly charismatic radio personality in the mid-20th century, and is often cited as a key influence on the development of hip-hop. He was known for his engaging and lively on-air presence, earning him the nickname “personality jock.”

As a gamer, I really dug this character’s vibe! It had everything – this cool, rhythmic way of talking, kinda like a rap before rap existed, and a whole sci-fi thing going on with a show called ‘Rocket Ship’. Apparently, this was all inspired by a local Baltimore DJ named Maurice ‘Hot Rod’ Hulbert back in the early 50s. I learned about this from a book called Voice Over: The Making of Black Radio by William Barlow – he goes into detail about it in a section called ‘Spin Doctors of the Postwar Era’.

Jocko hosted popular R&B shows at the Apollo Theater starting in the mid-1950s, featuring famous artists like Sam Cooke, Stevie Wonder, and the Supremes. However, Barlow argues that Jocko was a star performer in his own right, captivating audiences with his stage presence.

For Jocko’s dramatic entrance, the Apollo team created a full-scale rocket ship prop that lowered onto the stage. The descent was enhanced with smoke, lights, and realistic rocket sounds.

Jocko wore a real U.S. Air Force spacesuit during the shows, which Barlow says he got as part of a publicity campaign organized by the Pentagon’s space program.

Jocko’s television show, “Rocket Ship,” featuring a real rocket and spacesuit at the Apollo theater, is legendary and heavily inspired Parliament-Funkadelic’s idea of the Mothership – a spaceship that, like Jocko’s rocket, would descend onto the stage during performances. George Clinton even directly quotes one of Jocko’s well-known rhyming patterns at the start of “Mr. Wiggles,” the first track on Parliament’s 1978 album, Motor Booty Affair.

While Jocko Henderson had a huge, futuristic persona, I think the real reason he and other Black DJs were so popular and important to hip-hop was their ability to control and shape the music itself.

Hearing a DJ like Jocko Henderson on a New York City station like WADO was captivating not just because of his skill with rhymes, but also because he used his equipment – what he called his “record machine” – to powerfully enhance his delivery.

Jocko had complete control over his show, able to select music, talk or sing over it, share fan messages, and decide where and how to include advertisements.

Jocko was a powerful speaker who captivated audiences, and his voice on the radio felt incredibly controlled and dynamic. This skill allowed him to excel in the back-and-forth exchange between speaker and listener – a key element of African American communication, often referred to as ‘Black Dialogue,’ a term highlighted by the hip-hop group The Perceptionists in their 2005 album of the same name.

The DJ gained a powerful image through radio, and hip-hop artists embraced that influence by incorporating it into their music – both by using samples and by rapping over the DJ’s tracks.

However, it’s important to note that hip-hop wasn’t the first time the influence of radio DJs shaped how music was created.

You know, when I think about the roots of sampling in hip-hop, it actually goes way back to the ’50s and ’60s – around the same time Jocko Henderson was getting popular. There were these funny records called “break-in” records, and they were made by literally cutting and splicing tape together. Basically, people would take bits and pieces of different songs and remix them into something totally new – it was a really early form of what we now call sampling!

I was digging into the history of those really early novelty records – you know, the ones where artists kinda ‘broke in’ to existing songs – and I found out a lot of them came from this team, Bill Buchanan and Dickie Goodman. They actually started way back in 1956 with a track called “The Flying Saucer” on Luniverse Records! I found a super detailed history of them and that song on a blog called Way Back Attack by Michael Jack Kirby – it’s a great read if you’re into this stuff.

Essentially, “The Flying Saucer” was made by combining pieces of lyrics and music from popular 1950s rock and roll songs and weaving them into a funny science fiction story created by Buchanan and Goodman.

The sketch used snippets of songs by artists like Little Richard and Fats Domino to make it seem like they were part of the scene. Buchanan and Goodman likely provided the voices for all the other characters, including the radio DJs, news reporters, scientists, and the alien.

“The Flying Saucer” playfully imitated the science fiction movies about space that were popular at the time, like Robert Wise’s 1951 film, The Day the Earth Stood Still.

As Michael Jack Kirby noted, the news report style of “The Flying Saucer” recalled earlier radio dramas, especially the 1938 CBS broadcast of The War of the Worlds from Mercury Theatre on the Air. This episode, adapted from the 1898 H.G. Wells novel, was narrated and directed by Orson Welles, the show’s primary creative force.

Returning to hip-hop, Buddy Holly’s “The Flying Saucer” was used as a sample in 1985 for a mix called “History of Hip-Hop Mix,” also known as “Lesson 3.” This mix was part of a series of sample-based tracks called “lessons” released by Tommy Boy Records. The series began in 1983 with “Lesson 1,” or “The Payoff Mix,” a remix of G.L.O.B.E. and Whiz Kid’s song “Play That Beat Mr. D.J.” This remix won a contest held by Tommy Boy, challenging artists to create a new version of the track.

As a huge fan of both Orson Welles and James Brown, it’s amazing to me that the famous War of the Worlds radio broadcast actually ended up in a James Brown song! They used a clip of one of the announcers – I think it was Dan Seymour – in a track called “Lesson 2,” which people also know as the “James Brown Mix.” It’s a really cool connection between two totally different worlds of entertainment.

In a recent video, producer and YouTuber El Train delved into the history of hip-hop mixes and sampling, focusing on the work of Double Dee and Steinski. He explained how their innovative techniques paved the way for artists like DJ Shadow and Cut Chemist (formerly of Jurassic 5).

I’m discussing Buchanan & Goodman’s “The Flying Saucer” to illustrate how the influence of a radio DJ moved into recorded music. The record intentionally sounds like a radio show, and it’s made by combining pieces of different songs – a technique I think was inspired by a DJ’s ability to control what music listeners hear and how it’s presented.

Just like collage, hip-hop sampling lets artists take existing recordings and creatively reshape them to express their own ideas.

Okay, so you don’t just have to mess with the actual music files to change things up. I realized you can actually do it with your voice – it’s a totally different way to control what’s playing, and honestly, it’s pretty cool!

Before hip-hop, consider the 2019 documentary Ella Fitzgerald: Just One Of Those Things, directed by Leslie Woodhead. It features people discussing Ella Fitzgerald’s legendary improvised performance of “How High The Moon” in Berlin in 1960, with accompaniment from The Paul Smith Quartet.

After famously forgetting the words to “Mack the Knife” during a Grammy-winning performance – and playfully filling the gap with an impression of Louis Armstrong – Ella Fitzgerald repeated the feat with “How High the Moon.” This time, she improvised a five-minute vocal performance using scat singing instead of remembered lyrics.

In this impressive performance, Fitzgerald manages to weave in references to over 40 different songs. These include everything from classic jazz and orchestral pieces to familiar nursery rhymes, show tunes, and both traditional folk songs and playful novelty numbers.

According to music critic Will Friedwald, Ella Fitzgerald’s performance included songs like “Love in Bloom,” “Deep Purple,” “The Peanut Vendor,” “I Cover the Waterfront,” “Ornithology,” “Gotta Be This Or That,” and “Hawaiian War Chant.” She also performed her signature song “A-Tisket, A-Tasket,” originally recorded with Chick Webb, and a rendition of “Smoke Gets In Your Eyes” where she playfully changed the lyrics to “sweat gets in my eye” because she was working up a sweat during the energetic show.

Although Ella Fitzgerald wasn’t a hip-hop artist, the way she blended references to many songs in 1960 feels surprisingly similar to how a hip-hop DJ or producer samples and mixes different tracks today.

I believe Ella Fitzgerald’s vocal style is remarkably similar to the innovative way Grandmaster Flash constructed his 1981 mix, “Adventures of Grandmaster Flash on the Wheels of Steel.” Both artists essentially build something new by skillfully combining existing elements.

Grandmaster Flash became famous for his innovative DJ skills, seamlessly blending tracks from artists like Spoonie Gee, The Sequence, Blondie, Chic, The Incredible Bongo Band, Queen, and The Furious Five to create something new.

Flash famously sampled the beginning of actor and radio announcer Jackson Beck’s introduction to the 1966 record, Official Adventures of Flash Gordon. He edited the clip to remove the name “Gordon,” making it sound like Beck was saying “The official adventures of Flash” – essentially creating a custom introduction. This edited clip is also where the song got its title.

Okay, so here’s a fun little detail – about four years after that first use, they actually sampled that same Jackson Beck clip in Schoolly D’s “P.S.K. – What Does It Mean?”! But this time, DJ Code Money chopped it up even more, so all you hear is “The official adventures of…” It’s a really short snippet, but I always recognize it when I hear the song.

I’m comparing Ella Fitzgerald and Grandmaster Flash, along with DJ Code Money, because they all show incredible control over music. Each artist has a unique way of taking pieces from many different songs and blending them together to create something new.

I’ve noticed something really cool when I listen to a lot of rappers. They’re kind of like jazz musicians, especially when I think about Ella Fitzgerald’s incredible version of “How High The Moon.” It’s like they use their voices and lyrics to remix songs on the fly, improvising and blending things together – it’s a similar vibe to a really good jazz solo.

Grand Puba’s 1995 song “I Like It (I Wanna Be Where You Are)” blends rapping and singing with references to many classic R&B songs, including tracks by Michael Jackson (as the title suggests), The Force M.D.’s (“Tears”), and The Stylistics (“You Are Everything”).

Mark Sparks’ song “I Like It” features a sample taken directly from the chorus of the DeBarge song with the same title. Instead of sampling, Grand Puba could have recreated the song’s sound using his own voice, a technique he frequently employed.

If both DJs and MCs manipulate music to suit their own styles, it naturally leads us to ask: what are they trying to achieve by doing so?

Simply put, hip-hop artists want to excite the audience and get them engaged. But looking closer at how they do that reveals a deeper desire: to truly connect with people on a personal level.

Simply put, hip-hop often directly presents itself as a culture for young people – kids, teens, and young adults. I think this focus has been present since the very beginning of the genre.

Around seven minutes into the 1982 film Wild Style, directed by Charlie Ahearn, the movie features a fast-paced sequence of graffiti art. The montage showcases impressive pieces on trains, in sketchbooks, and painted on walls.

Throughout the artwork, a common thread is the repeated appearance of characters from comics and cartoons. The montage features familiar faces like Dick Tracy, Popeye, Donald Duck, and Richie Rich. Most notably, the central character, played by graffiti artist Lee Quiñones, is inspired by the classic hero Zorro, adopting a similar masked persona and tagging style within the film.

Back in 1978, artist Lee Quiñones became well-known for painting a mural featuring the Marvel Comics character Howard the Duck at Corlears Junior High School in Manhattan’s Lower East Side.

As a huge fan, what really struck me about the graffiti in Wild Style was how clearly it captured a young, energetic vibe. And honestly, the way hip-hop plays with sound feels the same way – it’s always been about that raw, youthful energy, and still is today.

In his 1984 book, Hip Hop: The Illustrated History of Break Dancing, Rap Music, and Graffiti, Steven Hager describes a well-known DJ competition around 1977 between Afrika Bambaataa and Disco King Mario, as detailed in the chapter “Herculords at the Hevalo.”

Bambaataa, who would later be called the “Master of Records” for his unique musical choices, began his sets in an unexpected way. He’d start with the theme song from The Andy Griffith Show (1960-1968) and then play the theme from The Munsters (1964-1966), both layered over a drum break. He’d even record the Andy Griffith theme directly off his television. After these themes, he’d move into James Brown’s “I Got The Feelin’.”

Around the same time, Kenny Wilson, an engineer working in the Bronx, also creatively used television in a mixtape he made. This mixtape, titled “Live” Convention ’77-’79, was an early version of the “Live” Convention albums that came out in the early 1980s on Johnny Soul’s Disc-O-Wax label—a label I briefly discussed in a previous article about live hip-hop performances.

The planned 1981 release of

According to Kenny Wilson, as he shared in an interview accompanying the 2007 release of “Live” Convention ‘77-79’, the project started around 1978. He wanted to combine pieces from various hip-hop tapes from the late 70s that his brother Reggie had collected and sold – a popular practice at the time.

Kenny wanted to create a collection of the best recordings from that time. He planned to use his editing talents to combine audio from various tapes in Reggie’s collection and enhance the sound quality, which was often poor because many were copies of copies.

To fix the sound problem, Kenny recorded the instrumental breakbeats directly to a reel-to-reel tape and then layered in the vocals from Reggie’s recordings. He also creatively sequenced the “Live” Convention performance by lengthening the breakbeats and mixing in audio from other sources to play during those extended sections.

The track featured audio from Jalal Mansur Nuriddin’s 1973 album, Hustlers Convention, a hugely important record in the development of hip-hop, known for its style inspired by traditional African American storytelling, particularly the boasts and rhymes of hustlers. It also included samples from several TV shows, like The Six Million Dollar Man and Fat Albert and the Cosby Kids, although the Fat Albert sample was later removed.

These examples – like using TV sounds in music or comic book characters in graffiti – demonstrate that hip-hop has always drawn inspiration from popular culture and children’s media. This shows that, at its heart, hip-hop is about young people expressing themselves and connecting with each other.

Beyond the music your family might have played, what kids see in movies, on TV, or in comics often finds its way into their artwork. This influence then frequently appears in hip-hop, showing up in lyrics, DJ techniques, and the way music is produced.

For instance, LL Cool J’s 1987 song “My Rhyme Ain’t Done” features the rapper delivering imaginative verses where he journeys through different historical and pop culture settings in America. He rapidly moves between these worlds, repeatedly stating that his rap is far from over.

In this song, LL Cool J reimagines history, telling stories like performing at Ford’s Theatre right before Abraham Lincoln’s assassination, being pulled into a TV and meeting the cast of The Honeymooners, and even finding himself in a cartoon world jamming with Spider-Man, Charlie Brown, and Snoopy in a comic strip band.

Similar to how Grand Puba blended sounds on “I Like It (I Wanna Be Where You Are)”, this song uses lyrics to combine different media elements – almost like a DJ mixing tracks on a turntable or creating a mixtape. Considering LL Cool J was only 18 when he recorded “My Rhyme Ain’t Done,” it’s fitting that he included a verse about cartoons.

Several hip-hop artists have sampled or referenced the educational cartoon Schoolhouse Rock! For example, both De La Soul and Compton’s Most Wanted used material from the Multiplication Rock series (originally aired from 1973 to 1985) in the very first songs on their albums.

De La Soul’s 1989 song “The Magic Number,” from their first album 3 Feet High and Rising, heavily borrows from Bob Dorough’s “Three Is A Magic Number.” The song was produced by Prince Paul and the group themselves, and it’s notable for its extensive use of samples – including “Lesson 3” by Double Dee and Steinski, just to name one.

Compton’s Most Wanted sampled the start of Blossom Dearie’s song “Figure Eight” as the introduction to their 1992 album, Music To Driveby. MC Eiht and DJ Slip produced this intro segment.

I called this section “Scratching a Record of My Life” to highlight how artists – whether it’s LL Cool J referencing cartoons or Compton’s Most Wanted sampling Schoolhouse Rock! – use music to express their identity and background. They’re all using sound to tell their stories.

Hip-hop artists frequently borrow sounds from popular culture to connect with listeners. These sounds were common during both their childhoods and those of their audience, making them a relatable and enjoyable way to express themselves.

In hip-hop, artists often see themselves as a constantly evolving story, needing to identify and share meaningful experiences and perspectives with their audience in a creative way.

Read More

- The Most Anticipated Anime of 2026

- Crypto’s Broken Heart: Why ADA Falls While Midnight Rises 🚀

- ‘Zootopia 2’ Smashes Box Office Records and Tops a Milestone Once Held by Titanic

- Actors With Zero Major Scandals Over 25+ Years

- When Markets Dance, Do You Waltz or Flee?

- Child Stars Who’ve Completely Vanished from the Public Eye

- SOXL vs. QLD: A High-Stakes Tech ETF Duel

- Aave DAO’s Big Fail: 14% Drop & Brand Control Backfire 🚀💥

- BitMine Bets Big on Ethereum: A $451 Million Staking Saga! 💰😄

- Crypto Chaos: Hacks, Heists & Headlines! 😱

2025-10-26 16:03