The stock market is soaring-or, at least, it is for some. Others, like Opendoor Technologies (OPEN), watch helplessly as the rising tide lifts them with it, a spectacle of strange and illogical motion, like some uninvited guest at a party one is not entirely sure was ever meant to be there in the first place. Launched into the public eye in 2020, the company’s stock has plummeted-no, has evaporated-by over 95% from its previous peaks, only to find a peculiar rebirth, driven not by reason but by the fevered optimism of large investors and the erratic enthusiasm of meme traders.

Now, a 500% increase year-to-date, a tenfold jump from the depths of despair in June-one might think it an invitation to hope. But the cold, indifferent market cap of $7 billion, with its stock priced at a mere $9.50 as of September 15, mocks any sense of coherent judgment. Even at this modest valuation, Opendoor remains below its debut price-after merging with a special purpose acquisition company (SPAC)-as though all that has occurred is an elaborate form of futility, the company stumbling blindly through a marketplace that demands precision.

So the question lingers, like an unanswerable riddle: is this, beneath $10, a stock worth buying?

A New CEO, or Just Another Bureaucratic Shift?

In an attempt to break free from its tormented trajectory, Opendoor’s board has made an incongruent decision-replacing its CEO, Carrie Wheeler, in August, as though a simple change in leadership might somehow unlock the shackles of its deeply ingrained inefficiencies. They have turned to Kaz Nejatian, the former COO of Shopify, a man whose success in building technology businesses will, it is hoped, be transferred-effortlessly, perhaps-to the troubled real estate market.

Nejatian’s plans, it seems, are predicated on a curious assumption: that a shift away from the work-from-home model will somehow ignite innovation within Opendoor’s already strained infrastructure. The logic here is impossible to fathom, like an automaton being wound up only to begin its purposeless march towards the same obscure destination. Yet Nejatian, ever confident, will attempt to apply the same methods that made Shopify a success. He will “transform” the company, or so it is said, bringing along Keith Rabois and Eric Wu to bolster the board-a band of founders returning to their creation, though one wonders what they have learned from the past.

As Nejatian takes up the reins, Rabois, in an interview on CNBC, expressed plans to trim the company’s workforce, which has bloated to unmanageable proportions. The promise of cost-cutting, of getting rid of inefficiencies, sounds more like the necessary maintenance of a machine that will continue its inexorable malfunction, rather than a true revitalization. The changes, they assure, will come-but when? How? One can only wait, like a prisoner awaiting the next bureaucratic decree that will either free or condemn them to further, unanswerable tasks.

The Mirage of Growth and Profitability

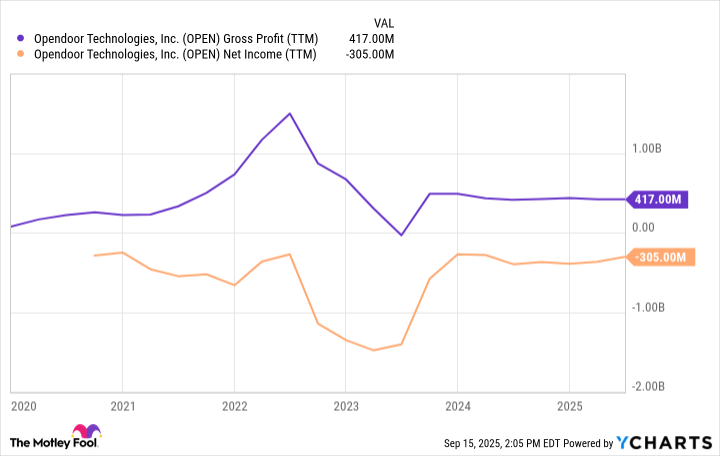

For Opendoor, growth is not an aspiration but a desperate need-one that seems increasingly out of reach. Last quarter, the company posted revenue of $1.6 billion. Yet, this revenue hides the cruel paradox of the business model: low gross profit margins. Opendoor earns only the spread between its purchase and selling prices of homes, a meager amount that is dwarfed by the escalating costs of operating such a business.

At the close of the last quarter, Opendoor’s gross profit stood at a mere $128 million, a pittance compared to the vast expanse of its operational expenditures. A marketing budget of $86 million, general overhead of $28 million, and $21 million dedicated to product development-these are the tolls extracted from the already thin profit margin. Coupled with $36 million in interest expense, the company posted a loss of $29 million, a grim reminder of its inability to generate positive net income over the past year.

And so, the cycle continues, a Sisyphean struggle to make ends meet. In the short term, cost reductions are necessary-a painful but inevitable requirement. In the long term, Opendoor seems to hope for a miracle: diversification into title services, mortgages, and partnerships with real estate agents. But what does this strategy entail? Is it truly a path to salvation, or just another delusion masked by grand promises?

The astute investor would do well to keep a watchful eye not on the company’s rhetoric, but on its ability to convert its gross profit into meaningful net income. Until that feat is accomplished, the narrative remains one of endless futility.

The Dread of Valuation Under $10

And here we arrive at the crux of the matter: the valuation. A market cap of $7 billion, a price-to-gross-profit ratio of 20-these figures are not mere numbers but reflections of an existential dilemma. Can a company that has yet to achieve profitability justify such high expectations? The answer is elusive, buried beneath layers of half-baked theories and misplaced hopes. The price-to-earnings ratio (P/E) is an impossibility here, as Opendoor loses money by every metric. Thus, we are left with the price-to-gross-profit ratio as a crude compass, though its direction is unclear.

The expectations placed on Opendoor are the same as those placed on a prisoner who is expected to perform an impossible task. There is no question of whether the task can be completed; it is only a question of how long it will take before the inevitable failure becomes apparent. Investors should refrain from viewing Opendoor as an opportunity-it is merely another cautionary tale, a bizarre dance of expectations that will only be undone by the cruel machinations of reality.

So, is Opendoor a buy under $10? Perhaps the real question is: can one ever truly buy hope, or is it simply a fleeting illusion? 🌀

Read More

- 39th Developer Notes: 2.5th Anniversary Update

- Shocking Split! Electric Coin Company Leaves Zcash Over Governance Row! 😲

- Celebs Slammed For Hyping Diversity While Casting Only Light-Skinned Leads

- The Worst Black A-List Hollywood Actors

- Quentin Tarantino Reveals the Monty Python Scene That Made Him Sick

- TV Shows With International Remakes

- All the Movies Coming to Paramount+ in January 2026

- Game of Thrones author George R. R. Martin’s starting point for Elden Ring evolved so drastically that Hidetaka Miyazaki reckons he’d be surprised how the open-world RPG turned out

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Here Are the Best TV Shows to Stream this Weekend on Hulu, Including ‘Fire Force’

2025-09-19 10:32