… with the images and paragraphs. Replace the original text with the Mel Brooks-style rewrite, keeping the structure but adding humor.

Check for the critical instructions: deepening analysis, no template content, proper formatting. Ensure that the humor is understated, not slapstick but witty. Maybe some wordplay on “valued” and “valuation.”

Make sure the final HTML is valid, with proper tags and no extra elements. Avoid using any span tags. Keep the images in place.

Double-check the title length. Once done, add the emoji at the end of the last paragraph.

For more than a century, no asset class has come close to matching the annualized return of stocks. This year, we’ve witnessed the broad-based S&P 500 (^GSPC), ageless Dow Jones Industrial Average (^DJI), and innovation-inspired Nasdaq Composite (^IXIC) explode to multiple record-closing highs. But let’s not mistake a parade for a permanent vacation-history has a habit of interrupting the festivities with a well-timed bear market.

But just because the stock market has proved historically unstoppable over multidecade periods, that doesn’t mean getting from Point A to B is without moments of “adventure.” Think of it as a rollercoaster with a map that says, “You are here,” but no exit signs.

As the S&P 500, Dow Jones, and Nasdaq Composite have soared to rarified territory, so have stock valuations. With the rise of artificial intelligence (AI) fueling extraordinary growth for Wall Street’s most influential businesses, investors have, collectively, been willing to turn a blind eye to historical valuation markers. But as the old adage goes, “What you don’t see can’t hurt you-until it does.”

But Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell may have spoiled the party by saying the quiet part out loud regarding stock valuations. Imagine a magician revealing the trick mid-performance-suddenly, the wonder is gone, and the crowd is left wondering if the rabbit was ever real.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell just highlighted the biggest historical risk to Wall Street

On Sept. 23, Powell gave a speech in Rhode Island where he fielded questions about the stock market and how the Fed’s Board of Governors account for equity valuations in monetary policy. Though the chair of the nation’s central bank typically avoids interjecting his opinion on the stock market, he made a somewhat candid observation: “We do look at overall financial conditions… but you’re right, by many measures, for example, equity prices are fairly highly valued.” Equity prices are fairly highly valued. It’s the financial equivalent of a librarian whispering, “This book is overdue,” while you’re mid-sentence.

We do look at overall financial conditions, and we ask ourselves whether our policies are affecting financial conditions in a way that is what we’re trying to achieve. But you’re right, by many measures, for example, equity prices are fairly highly valued.

The emphasis is these six words: “equity prices are fairly highly valued.” When the head of the Fed is making observations about the historic priciness of stocks, sweeping things under the rug or kicking the can no longer becomes an option. It’s like trying to hide a elephant in a teacup-eventually, the cup wins.

Loading…

–

For what it’s worth, Powell isn’t alone in cautioning Wall Street, investors, and everyday Americans about potentially inflated asset values. In December 1996, famed Fed Chair Alan Greenspan delivered a speech at the American Enterprise Institute, where he introduced the now well-known phrase “irrational exuberance” to describe a rapid increase in asset valuations during the advent and proliferation of the internet. It’s the financial world’s version of “This is fine,” while the house burns down.

While Greenspan rightly recognized that a game-changing technological advancement (the internet) had sent broad market valuations soaring, the S&P 500, Dow Jones Industrial Average, and Nasdaq Composite didn’t hit their dot-com peak until March 2000-more than three years after Greenspan delivered his “irrational exuberance” speech. History, it seems, loves to take its time-like a slow-cooked stew, but with more crashes.

In other words, the global growth potential AI brings to the table is an unquantified variable that has the potential to, at least temporarily, support historically high stock valuations. But no mistake, history has a (thus far) flawless track record when it comes to pricey stock markets-and Fed Chair Jerome Powell is keenly aware of it. It’s like a chess game where the opponent has already checked your king, but you’re still trying to move your knight.

This is the second-priciest stock market over the last 154 years

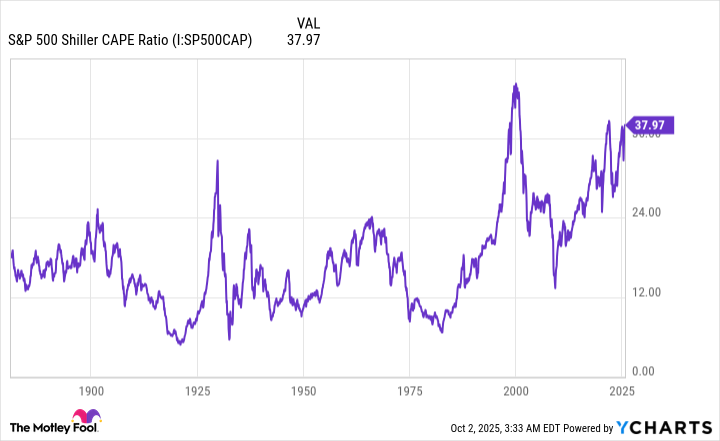

To be objective, there is no one-size-fits-all approach to valuing individual stocks or the broader market. The difference of opinion between investors over what’s cheap and what’s pricey is what makes the stock market a market in the first place. But there is one valuation measure that leaves virtually no room for argument: the S&P 500’s Shiller price-to-earnings (P/E) Ratio, which you’ll also find referred to as the cyclically adjusted P/E Ratio, or CAPE Ratio.

The S&P 500’s Shiller P/E is based on average inflation-adjusted earnings over the prior 10-year period. Whereas the traditional P/E ratio, which takes into account trailing-12-month earnings, can be easily tripped up by economic downturns, the ability of the Shiller P/E to account for a decade of earnings history effectively negates the impact of shock events. It’s the closest thing we have to an apples-to-apples valuation tool when looking back more than a century. Imagine a chef who insists on using a decade-old recipe to judge a modern dish-suspicious, but oddly precise.

When back-tested to January 1871, the S&P 500’s Shiller P/E has averaged a multiple of 17.29. It’s worth noting that Shiller P/E multiples have been pretty consistently higher than the 154-year average reading since the mid-1990s, which is when the internet broke down information barriers for everyday investors and gave them the confidence to invest in higher-growth businesses. It’s like a toddler learning to ride a bike-exciting, but with a 50% chance of a wipeout.

As of the closing bell on Oct. 1, the Shiller P/E chimed in with a reading of (drumroll) 40.04. This is just a stone’s throw away from its peak of 40.15 during the current bull market, and represents the second-highest multiple during a continuous bull market dating back 154 years. The only time stocks have been collectively pricier than they are now was in the months leading up to the bursting of the dot-com bubble. In December 1999, the Shiller P/E peaked at 44.19. It’s the financial equivalent of a party where everyone’s drunk, but no one’s ready to leave.

The reason this valuation data is meaningful is because the Shiller P/E has an uncanny ability to predict the future. Though it’s not a timing tool in any way-as noted, stocks remained historically pricey for years before the dot-com bubble burst-all five prior readings above 30 were eventually followed by pullbacks in the S&P 500, Dow Jones Industrial Average, and/or Nasdaq Composite ranging from 20% to 89% (during the Great Depression). It’s like a fortune cookie that’s always right, but never tells you when the bad news will arrive.

It’s becoming downright impossible to sweep a Shiller P/E multiple of 40 under the rug, regardless of how fast a handful of megacap companies are projected to grow in the coming years. It’s the financial version of trying to hide a elephant in a teacup-eventually, the cup wins.

Time is the silver lining for investors

If history were to rhyme in some form in the not-too-distant future, investors can expect a 20% or considerably greater decline in Wall Street’s major stock indexes. But the great thing about history is that it’s a door that swings, disproportionately, in both directions. It’s like a seesaw-what goes up must come down, but sometimes it just wobbles indefinitely.

The Shiller P/E has decisively shown that extended valuation premiums aren’t well-tolerated by Wall Street or investors, which eventually leads to significant downside for the S&P 500, Dow Jones, and Nasdaq Composite. Yet historical precedent also shows that stock market cycles are undeniably nonlinear. It’s like a rollercoaster with no track-exciting, but with a 100% chance of a crash.

In June 2023, the S&P 500 officially entered the current bull market by rising more than 20% from its 2022 bear market bottom. This is when Bespoke Investment Group posted the data set you see below that compared the calendar-day length of every S&P 500 bull and bear market dating back nearly 94 years to the start of the Great Depression (September 1929). It’s like a family tree, but with more crashes and fewer hugs.

Loading…

–

It’s worth pointing out that 27 separate instances where the S&P 500 fell at least 20% following a bull market were logged by Bespoke. This means bear markets are relatively normal and inevitable events. It’s the financial equivalent of a broken clock-right twice a day, but still a mess.

More importantly, the average bear market stuck around for just 286 calendar days, which works out to roughly 9.5 months. Further, none of the 27 bear markets since the Great Depression began endured longer than 630 calendar days. It’s like a bad relationship-short, painful, and over quickly.

On the other end of the spectrum, the average S&P 500 bull market has lasted 1,011 calendar days (about two years and nine months), with the current bull market, extrapolated to present day, marking the 14th bull market since September 1929 that’s endured longer than the lengthiest bear market. Time is the silver lining for investors. Given ample time, Wall Street’s major indexes can recover their short-term losses and eventually (based on what history tells us) push to new heights. It’s the financial version of a phoenix-rising from the ashes, but with a lot of smoke.

So, dear reader, as we navigate this market of peaks and valleys, remember: the only thing more predictable than a bear market is the human tendency to ignore the signs. But with a little patience and a dash of humor, even the most overvalued stocks might just surprise us. 🧠

Read More

- 2025 Crypto Wallets: Secure, Smart, and Surprisingly Simple!

- Gold Rate Forecast

- Brown Dust 2 Mirror Wars (PvP) Tier List – July 2025

- HSR 3.7 story ending explained: What happened to the Chrysos Heirs?

- ETH PREDICTION. ETH cryptocurrency

- Games That Faced Bans in Countries Over Political Themes

- Gay Actors Who Are Notoriously Private About Their Lives

- The Best Actors Who Have Played Hamlet, Ranked

- Banks & Shadows: A 2026 Outlook

- The 10 Most Beautiful Women in the World for 2026, According to the Golden Ratio

2025-10-04 10:23